The Wall of Awful

| January 16, 2024Everyone has these walls, but people with ADHD have more of them and they tend to be larger

The Wall of Awful

Hadassah Eventsur

L

eah stares at the pile of books on her dining room table. They’ve been sitting there for weeks, and small particles of dust have settled on the covers. Her pulse quickens just thinking about the unpleasant task of returning yet another round of overdue books, and she quickly turns her head and leaves the room.

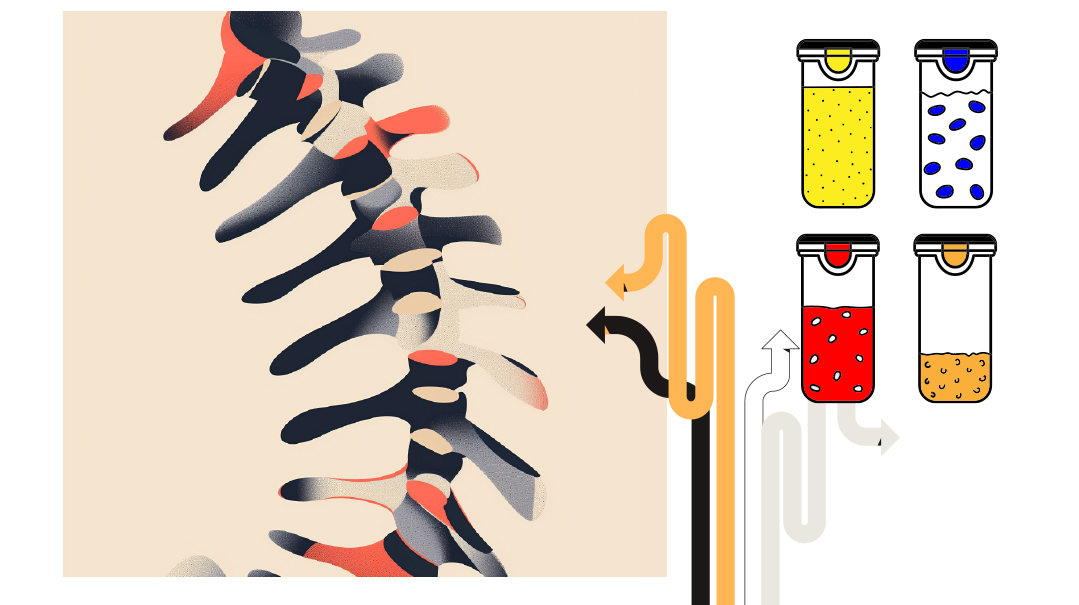

What Leah is experiencing is a “Wall of Awful” for a particular task. The Wall of Awful, a concept created by Brendan Mahan, an ADHD coach, posits that the emotional impact of repeated failures around a particular task creates a barrier or wall to completing it. The more one avoids a task, the more bricks are added to the wall. It could be a failure brick, a disappointment brick, a shame brick… there are no shortage of bricks that can be added. These bricks can be a result of letting ourselves or others down, fear of being exposed, or anxiety that comes from not meeting the mark.

Everyone has these walls, but people with ADHD have more of them and they tend to be larger. If you find yourself saying, “Why can’t I send back that form?” or “Why can’t I just call the bank and fix the money issue?” it’s probably because you have built up a Wall of Awful for that specific task.

There are five ways to approach these walls. The first way is to passively stare at the wall, noticing how tall and thick it is, with no idea how to move on.

The second approach is to attempt to go around it, which won’t work because the wall goes on indefinitely.

Those two strategies are avoidance. Rather than engaging with the task at hand, you’re stuck staring at the task, or you busy yourself with other less “awful” tasks.

The third way to approach the wall is to attempt to smash through it. This translates as using anger as a motivator — i.e., by bullying yourself to just get it done or berating the person making the request. These three methods correspond to the body’s stress responses of fight, flight or freeze. Smashing the wall is fight, going around it is flight and staring at it is freeze.

A more effective approach to get past the wall is to climb it. We climb a wall by using motivational strategies when approaching an undesirable task. It could look like listening to a podcast while folding laundry or dancing to music while vacuuming.

The final approach to getting past the wall is to build a door. We change our emotional state by increasing opportunity for dopamine releases. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter that activates the pleasure and motivational areas of the brain. Ideas for releasing dopamine include building in rewards for task completion, making postural adjustment such as sitting up straight or engaging core muscles, or increasing movement.

The next time you find yourself faced with a wall getting in the way of what you need to do, start thinking about what climbing a wall or building a door looks like to you. Doing this will help you see the wall for what it is, an imaginary obstacle that you have the strength to overcome.

Hadassah Eventsur, MS, OTR/L is a licensed occupational therapist with over 20 years of experience, and a certified life coach in the Baltimore, MD area.

Sad but Not Alone

Abby Delouya

WE

are living in times of deep sadness. Grief affects the brain, including emotional regulation, attention, memory, organization and the ability to multitask. People affected by grief may get sick more often, experience agitation, have difficulty sleeping, have headaches, body aches and pains, and digestive issues.

It can be very difficult to support a grieving spouse; no one grieves in exactly the same way, and figuring out how to be there for a loved one can be challenging. Some people may desire time alone to process their emotions, while others may fear being alone with their thoughts.

The most supportive way to show up for our partners in their grief is to offer acceptance and space for their process, and practical help as well.

- Listen, don’t advise. Try to tolerate watching and being in your spouse’s pain. Share memories.

- Help out practically where you can. Facilitate more sleep, help with the kids more and expect less — at least at the beginning.

- Allow space for your own pain. The sadness can be especially compounded by shared grief. It’s possible the primary mourner is your spouse, but secondary mourners are deeply grieving and hurting as well. If you need more space to hold your pain than your spouse can give, reach out to friends, other family, supportive community members, or a therapist for support.

- Don’t put a time limit on the grieving process. Grief cycles, and so while hopefully there will be times of deep healing and light, other times may find the one who has suffered a loss pulled back into their grief — sometimes predictably, sometimes not. Don’t judge the process — not your spouse’s nor your own.

- Learn something together in the merit of the person who was niftar. Connecting on a soul level is healing and grounding.

- Anticipate that special days, like the yahrtzeit or certain other times of year, can be especially painful and triggering. Ask your spouse directly what he or she may want to feel supported during these times.

Abby Delouya, RMFT-CCC, CPTT is a licensed marriage and individual therapist with a specialty in trauma and addiction.

Leap of Faith

Shoshana Schwartz

Has a lack of confidence ever held you back?

Imagine you’re embarking on a brand-new project. You do extensive research, create a detailed plan, organize your presentation… and then place it on a corner of your desktop, where it stays indefinitely because you’re not sure itwill succeed.

There are no guarantees so you might decide to wait until that confidence appears. Perhaps you try to tilt the odds in your favor with prayer, affirmations, or EFT tapping. But while these are all beneficial, at some point, you have to take a leap of faith. You can’t gain confidence in succeeding at something until you’ve actually done it. First you have to do it, and only then you can develop the confidence you seek.

The same concept applies to relationships — only the stakes are much higher. Of course, you first want to make sure the necessary components — such as honesty, reliability, and goodness — are there. But at some point, you have to take that leap of faith. How do you know if the person is actually trustworthy? By trusting them.

Like most investments, trust requires risk tolerance. It involves vulnerability. It’s scary, perhaps even paralyzing. Sure, you can keep that file on your desktop. Or you can start small, sharing certain authentic parts of yourself, and see what happens. You might be pleasantly surprised.

Complete trust is not a prerequisite for the beginnings of an honest relationship. First you engage in a trusting act such as sharing, then you learn to trust. That’s why it’s called a leap of faith.

Shoshana Schwartz specializes in compulsive eating, codependency, and addictive behaviors.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 877)

Oops! We could not locate your form.