The Seed Vault

There are thousands of crates, boxes and jars, all containing tiny treasures that scientists hope will save mankind in case of catastrophe

Photos: Crop Trust

From Syria to Svalbard

2012 – ICARDA Gene Bank, Tel Hadia, 20 miles south of Aleppo, Syria

The scientists at the gene bank were under a huge amount of pressure. The Syrian Civil War had broken out a year earlier, and bombs and gunfights had become the new norm. There was constant shelling, but the scientists got on with their work anyway. Now more than ever, their work was absolutely essential.

The International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) operated a seed bank, or gene bank, in the Aleppo suburb of Tel Hadia. The gene bank collected seed samples from farmers across the Middle East. The purpose of the gene bank, also known as seed bank, was to be a safe place for the region’s seeds. If disaster would strike and destroy lots of crops and seeds, the seed bank could send farmers new seeds. With war raging, the place could be bombed at any moment. Clearly, the seed bank in Tel Hadia was no longer safe;. The scientists were working overtime to ship their seed collection to a safer location.

Mariana Yazbek, the gene bank manager, watched her colleagues handle glass vials and foil packets as they prepared their precious seeds for shipment to the Svalbard vault. They were packing any types of seed they could get their hands on, from chickpeas to lentils to alfalfa sprouts. Everything had to be carefully labeled and recorded. Their work here would have an impact for generations. The civil war had already destroyed too many fields and crops — seeds that would never again sprout. ICARDA’s job was to make sure that the region’s many varieties of seeds would survive any calamity.

The seeds that they were packing up were the future of the Middle East. Four years earlier, in 2008, the Svalbard seed bank had opened (read more about Svalbard further on). The ICARDA gene bank in Syria had been among the first of the hundreds of gene banks worldwide to make a deposit of seeds to Svalbard. Back then, they had sent seed samples as a precaution, never dreaming that they would one day be in desperate need of a place like Svalbard. A shell fell in the distance with a boom. Mariana was grateful that the seeds had a new home to go to, even if it was across the world. In the Svalbard vault in Norway, the seeds would be cared for and protected until they could be planted.

Mariana shook her head as yet another shell whizzed nearby. The fighting seemed to be getting worse by the day. Her gene bank couldn’t last out here in Syria for much longer.

The Highs and Lows of Biodiversity

We’ll get back to Mariana and her seeds shortly, but in the meantime, are you ready for a teeny weeny little science lesson? Here we go!

First, here are a bunch of facts for you to mull over:

The 8 billion people on the planet, plus all the animals that we eat, are fed by food that grows.

Since the 1900s, more than 75% of fruit and vegetable varieties in the world have been lost. That means that due to certain factors, like pollution and construction on farmland, many produce varieties died out.

More than 60% of the world’s calories come from just three crops: wheat, rice, and corn.

There are about 20,000 edible plants on Earth. Historically, humans used 6000 plants to make food. Nowadays, fewer than 200 plants and crops make a significant contribution to food production.

Hmm, this is interesting but also slightly worrying information, wouldn’t you say? Agriculture is very important — without farmers toiling away in their fields, we wouldn’t have food to eat. But where are all those fruits, vegetables and crops disappearing to? And how can we get them back?

The answer lies in a very fancy word: biodiversity. Biodiversity means having a variety of living organisms. In our case, this is plants. So, biodiversity — having a large variety of plants — is a good thing: If you don’t like broccoli, you can always eat carrots. Or peppers, or cucumbers or… You get the picture. But it goes further than just picky eaters. In addition to varying taste buds, we also have varying climates. Plants and crops that thrive in the rainforests of Peru will shrivel up and die in the hot plains of Pakistan. Biodiversity enables farmers to grow crops that are suited to their climates.

Biodiversity also makes it possible for farmers to grow better crops. These can be plants that produce more fruit, and plants that are healthier and bug-free. Farmers experiment with different varieties, and often create new varieties, until they find one that does the job they want it to do. This can be both good news and bad news. It’s good news if it’s done carefully and with consideration. But when every farmer plants bug-free crops we start to lose plant varieties. That’s when we end up with low biodiversity.

Did you know that in the olden days, carrots were basically every color but orange? Back then, carrots were yellow, white and various shades of purple, but very rarely orange. In the 17th century, some Dutch farmers cultivated orange carrots, which became super popular. (Cultivation means trying to grow a certain type of plant.) Yellow, white and purple carrots pretty much disappeared from kitchens all over the world. In recent years, the old types of carrots have been making a comeback, but they’re still not as common as orange carrots. This is a great example of low biodiversity!

Purple carrots sure would be fun to eat. But low biodiversity usually has a much bigger impact than just the color of veggies. Let’s talk about wheat. What happens if the wheat in one country catches a disease? (Yes, plants also get sick!) If farmers all over the world have planted that same wheat variety, then all the world’s wheat could catch the disease. Bye-bye, bread. And cakes, and cookies.

High biodiversity means that farmers are planting all different types of wheat. So, even if one variety of wheat gets sick, we still have the other varieties.

Seed Banks

We’re done with the science lesson, so let’s move on to seed banks. There are about 1,750 seed banks across the world. In these storage facilities, seeds are preserved and protected so that they can be used for cultivation and research.

Preserving seeds means that even if there’s a massive drought, a huge earthquake, World War Three, or any other destructive disaster, we still have a way of growing plants — because we have the seeds in storage. Obviously, in the short term, any one of these catastrophes will affect crops and produce. But once things have calmed down, farmers will be able to withdraw seeds from the banks and replant their fields.

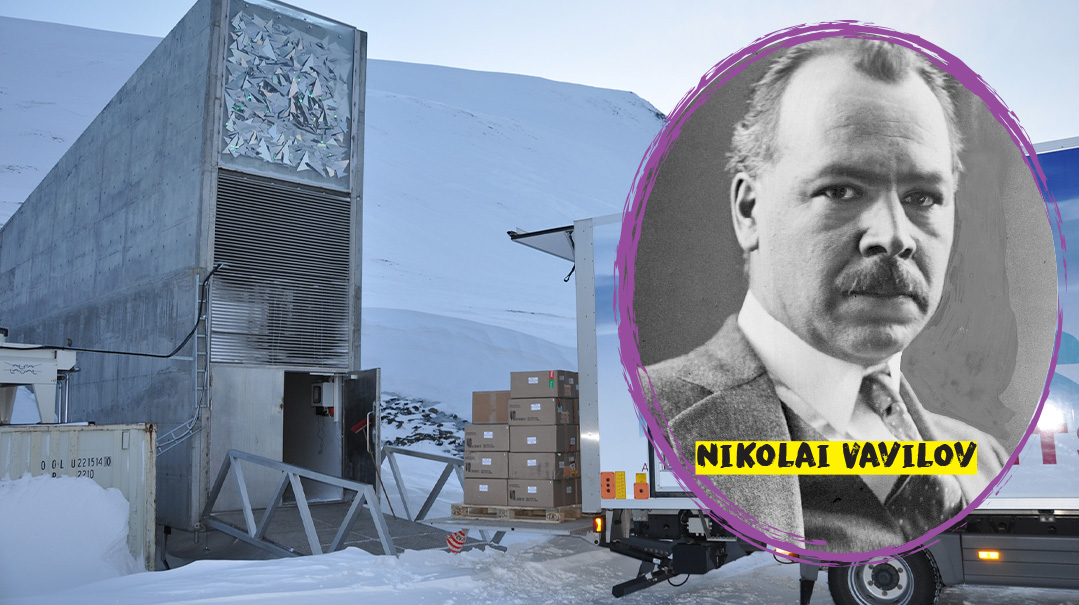

The first seed bank was founded by Russian botanist Nikolai Vavilov in St Petersburg in 1924. As a plant breeder, Vavilov understood the importance of having lots of different plants. He helped raise awareness about biodiversity. Since then, seed banks have sprouted everywhere. Different seed banks focus on collecting different seeds. For instance, the International Potato Center in Peru houses more than half of the world’s potato varieties (of which there are about 4000). The Millennium Seed Bank in Surrey, England, stores seeds from the UK’s entire native plant population. The Berry Botanic Garden in Portland, Oregon, has seeds from endangered plants of the Pacific Northwest. Guess what type of seeds are in the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines?

Just to give you an idea of how many seeds we’re talking about, the Vavilov Institute holds more than 325,000 seed samples. The Millennium Seed Bank has more than 2.4 billion seeds from about 40,000 kinds of plants.

The scientists at the seed banks are kept very busy. Besides for collecting and cataloguing seeds, they also need to cultivate some seeds in order to produce more seeds. Did you know that some seeds can lie dormant for centuries? That means that if they’re planted hundreds of years later, they will grow fruit! Other types of seeds aren’t so lucky. They expire after only 5-7 years, which isn’t good news for seed banks. In such cases, the scientists need to plant the seeds and wait for them to grow. Then they can collect the seeds from the fruit to restock the seed supply. And they have to repeat this every few years!

The Doomsday Vault

Having seed banks all over the world is a fantastic idea. But it’s not a completely foolproof solution. Just look at what happened in Syria. Civil war all but destroyed the nation’s fields and could have destroyed the gene bank too. If not for Mariana Yazbek and her fearless colleagues, decades of work and thousands of seed varieties would have been lost forever.

Seeds have to be stored in very specific conditions. The underground vaults at the Millennium Seed Bank are protected against floods, bombs, and radiation. But what happens if the cooling system in the vaults malfunctions? Even the seemingly indestructible Millennium Seed Bank is vulnerable to computer hackers and terrorists.

In the early 2000s, the world’s governments agreed that while their seed banks were all doing an admirable job, the planet needed an insurance plan. And so, they decided that every single seed in all of the world’s seed banks should be backed up by another one in a separate facility. That facility would have to be a fortress, located somewhere very remote, and preferably with a built-in cooling system in case of technological malfunctions. What they were looking for was a doomsday vault — a vault that would withstand the very worst-case scenario.

The perfect location for such a vital facility was Svalbard, Norway. Svalbard is the farthest north one can travel to on a scheduled flight, but it’s still in the middle of nowhere so there’s practically no risk of civil war or terrorist attacks. The climate is dry and cold, exactly the conditions needed to preserve seeds. The area is geologically stable and high above sea level, so it’s not at risk of flooding, earthquakes, typhoons, tsunamis, hurricanes or any other freak weather event that could destroy a seed bank. The underground vaults are deep enough into the bedrock to protect the seeds from nuclear explosions. And the permafrost (ground that is always frozen) provides a natural cooling system, in case the state-of-the-art one fails.

Svalbard’s mission is to house as much of the world’s seed population as possible. The vault has the capacity to store 4.5 million seed varieties for a maximum of 2.5 billion seeds.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is literally a vault. It has maximum security, so please don’t try to rob it. Like with any bank, the seeds that are held at Svalbard may only be withdrawn by the organization that deposited them.

New Beginnings

We haven’t finished with Mariana and ICARDA. The seed bank manager and her team were able to transfer 116,000 seeds (or about 83% of all their seeds) from Syria to Svalbard before being forced to abandon the seed bank in 2014. By 2015, they were anxious to get back to work. After all, a large part of what ICARDA does is distributing seeds to farmers who need them. Returning to Syria was not an option, however. Instead, they turned to Lebanon and Morocco, where the climate is similar to Syria.

After setting up temporary gene banks in those two countries, ICARDA became the first (and currently the only) seed bank to make a withdrawal from Svalbard. They took just 300 seed samples from each variety that they had deposited and began the nerve-wracking job of planting them.

It was painstaking work. The scientists couldn’t sleep at night for worry. With such a small number of seeds to begin with, they couldn’t afford for any of them to go to waste. Their precious new saplings were in danger of drought, wildfires, disease and infestation — anything could go wrong. The scientists held their breaths, until finally the crops grew and with them, a new batch of seeds.

Over a period of five years, the team at ICARDA was able to successfully grow more than 100,000 of their original seeds They revived crops that had come too close to disappearing! They even managed to send 81,000 new seeds to Svalbard. Today, ICARDA sends seeds to scientists and farmers across the world who need to experiment with drought-resistant crop varieties.

Who knew that a tiny seed could be so important?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Jr., Issue 928)

Oops! We could not locate your form.