The Secrets of the Old City

Join tour guide Avi Flax as he reveals to us the secrets that are hiding in plain sight

Photos: Blimie T Photography

Exploring the streets of Yerushalayim’s Old City never gets old! There are more than 2,000 years of Jewish history lurking behind every stone, and you’re bound to walk straight past some secrets. Unless you’re walking with someone who knows everything there is to know, of course. So grab your baseball cap and water bottle, and join tour guide Avi Flax as he reveals to us the secrets that are hiding in plain sight.

Har Zion and Dovid Hamelech

WE

meet Avi at the first stop on our tour, inside the walls of the Old City at Shaar Zion. This is one of the seven gates in the walls around the Old City. Avi says there is somewhere very special he wants to show us before we enter the Old City. He leads us through the massive archway and down a nearby street. We’ve left the Old City and are in Har Zion. We can’t help but notice a large monastery towering overhead.

After walking for about a minute or so, we find ourselves in a large courtyard.

“Just through that archway,” Avi says as he points, “is what is called the kever of Dovid Hamelech.” Legend has it that this is the site of Dovid Hamelech’s burial place, although it’s not certain that this is true. According to Tanach, Dovid Hamelech was buried in Ir Dovid, which most experts agree is across the valley. But nowadays, this site draws lots of Jewish visitors who come here to daven. And since this might be Dovid Hamelech’s kever, we step inside and say a kapitel Tehillim.

When we’re finished davening, Avi tells us a fascinating story that took place during a period in history when the kever was under Muslim control. There was a Jewish woman in the Old City who did laundry for people in the area. One of her customers was the Arab guard of the kever. One day, she asked him to let her daven at the kever in lieu of payment. So he took her to the kever, and then locked the gate to the compound with her inside. He ran to the Arab authorities, informing them that a Jewish woman had come to pray at the kever. The laundry woman realized that she was in grave danger and davened for a yeshuah. Suddenly, an old man with a long beard and glowing face appeared. He motioned for her to follow him. He led her through a tunnel which brought her to the safety of the Jewish Quarter in the Old City. Was it Dovid Hamelech who saved her?

We can’t leave before seeing the roof, Avi tells us. When we make it up there, we see what he means. Before us is a magnificent view of Har Hazeisim and the Silwan valley.

“For many years, this rooftop was the closest that the Jews of Yerushalayim could get to the Kosel,” Avi informs us. After the Israeli War of Independence in 1948, the Jews had to move out of the Old City and could no longer daven at the Kosel. Instead, they would climb to this very rooftop, from which they could see Har Habayis. This rooftop saw a lot of tears, until the Kosel once again became accessible to Jews in 1967.

But I’m confused. I can’t see Har Habayis from here at all. Avi assures me that back then, the trees on our left were not around, and so people had an unobstructed view all the way to the Makom Hamikdash.

The Walls of Yerushalayim

We’re back at our starting point, only this time we’re looking at Shaar Zion from outside the Old City. Avi asks us if we notice anything unusual about the stones on this part of the wall. We immediately realize that they’re riddled with holes. “Bullet holes,” Avi confirms. This was the site of a fierce battle in 1967, as Israeli soldiers fought to take over the Old City.

Now Avi tells us the significance of the walls around the Old City. The ancient city of Yerushalayim has had walls surrounding it since before the times of Yehoshua bin Nun. In ancient civilizations, cities were fortified to protect against conquering armies. But Avi tells us that the walls of Yerushalayim also have important halachic ramifications.

For instance, during the times of the Beis Hamikdash, the korban pesach could only be eaten in Yerushalayim. The walls indicated the boundaries of the city, so the korban pesach had to be eaten inside the walls. Another example is the metzorah. If someone had tzaraas, he was sent outside the city’s walls.

Yerushalayim has always been the grand prize for invading armies. Everyone wants a piece of her. Her walls have been broken down and rebuilt many times throughout history. The wall that exists nowadays was built in the 1500s by the Turkish sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.

Avi tells us an interesting tidbit. About 300 years before Suleiman’s time, Eretz Yisrael was ruled by another Muslim ruler, called Al-Malik. At the time, Yerushalayim was in danger of being conquered by the Crusaders. Al-Malik ordered the reconstruction of the city’s walls (which had been badly damaged in an earthquake two hundred years earlier, and never properly restored). But seven years into the construction, he changed his mind! He decided that the walls were too strong, and if the Crusaders would conquer the city, they would reap the benefits . So he ordered the walls to be torn down. Yerushalayim remained defenseless for the next three hundred years, until Suleiman rebuilt the walls.

The Four Synagogues

WE

walk through the south parking lot to the Four Sephardi Synagogues.

This is a courtyard shared by four old Sephardi shuls. Remember that story about the laundry woman who escaped the kever of Dovid Hamelech via a tunnel? Avi tells us that the tunnel led her somewhere near here.

The oldest of the four shuls is the Beis Haknesses R’ Yochanan ben Zakai. In this shul, there is a shofar and a flask of olive oil waiting to be used when Mashiach arrives. This is also where the new Sephardi chief rabbi is appointed.

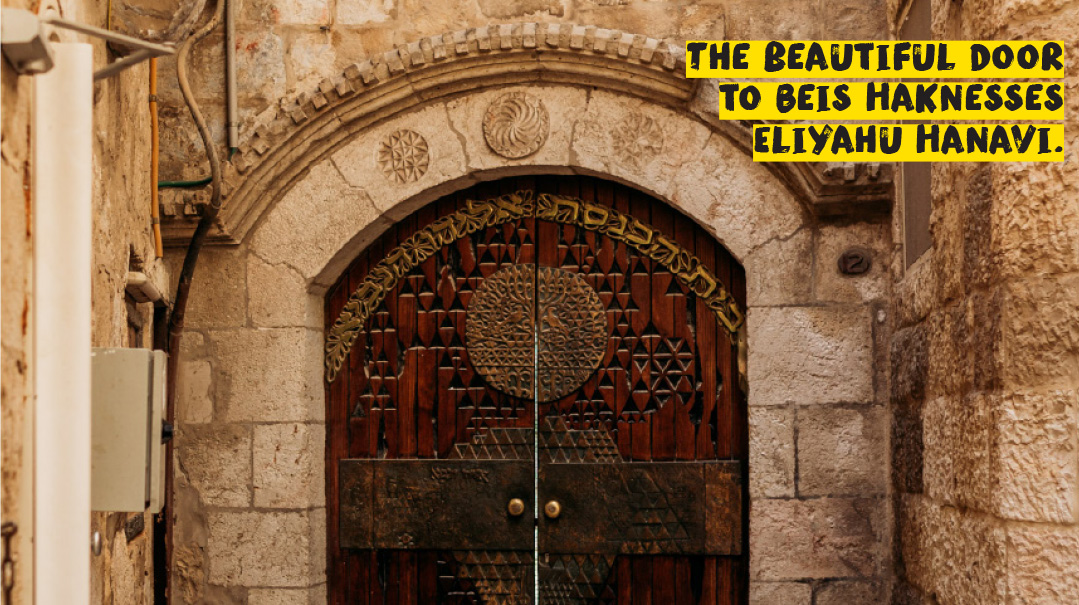

Another of the shuls is Beis Haknesses Eliyahu Hanavi. Legend tells of one Yom Kippur night when there was one person missing from the minyan. Suddenly, a tenth man appeared. He stayed until the end of Yom Kippur, at which point he disappeared. After this story, the shul was named for Eliyahu Hanavi.

Houses of Protection

Avi leads us through an archway and we find ourselves in a quiet little neighborhood with narrow alleyways and arches. This place is very photogenic! Sure enough, we pass a bar mitzvah boy and his family, all dressed for the simchah, as they pose for their photographer.

Avi explains why these streets are so narrow. “During the 1800s, Jews began to arrive in Eretz Yisrael from Lithuania and Russia. The Arabs controlled the Old City, which is the only place in Yerushalayim where people were living at the time. The Arab landlords demanded crazy prices. In order to rake in as much rent money as possible, they extended their buildings into the streets and even built over the streets. That’s why so many streets in the Old City are covered by buildings.”

There was terrible overcrowding. In 1858, Baron Rothschild purchased a plot of land in the Old City and built a large complex. The neighborhood became known as Batei Machse, which means “houses of protection.” There were 100 apartments! Each apartment had two rooms and a kitchen. This was a luxury back then. Today, only one such building remains.

As we walk through the streets of Batei Machse, we hear the beautiful sounds of young boys learning Torah. Avi tells us that several buildings in this neighborhood, including the original Batei Machse building, house the famous Silberman Cheder. This cheder has a unique way of learning. And it is open every single day of the year, including Tishah B’Av!

Yeshivah for Mekubalim

WE

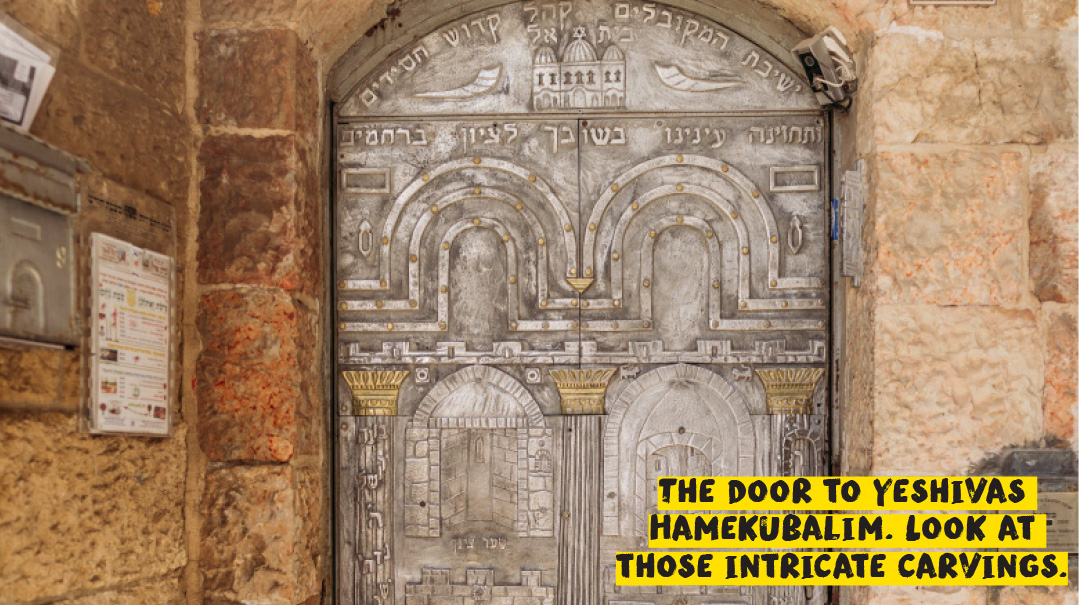

head deeper into the Old City. If not for Avi, we definitely would have walked straight past this door without a second glance. And wouldn’t that be a shame? Just look at those intricate carvings!

This is the famous Yeshivas Hamekubalim Beis Keil. As always, Avi has a story for us.

In the early 1700s, there was a boy in Yemen called Shalom Sharabi. He sold rugs in the street. One day, a non-Jewish customer asked him to bring a rug to her house. Once Shalom was in the house, she locked the front door. Shalom immediately realized that it was an issue of yichud. He also realized that the woman had some plan for him, like marrying him off to her daughter. He convinced the woman to take a look at the rug in the sunlight on the porch. He stood there on the porch, several stories high, and made a promise. “Hashem, if You save me, I will go to Yerushalayim.” In those days, travelling from Yemen to Yerushalayim was a long and dangerous journey. Shalom jumped off the porch to escape the woman and her evil plans, and miraculously survived!

He kept his promise and journeyed to Yerushalayim. He came across this yeshivah for mekubalim and became the janitor. One day, a question arose but none of the mekubalim, not even the rosh yeshivah Harav Gedalia Chayon ztz”l, knew the answer. The next day, Rav Gedalia opened his sefer and was shocked to discover a note inside that explained the answer to the question!

Eventually, they realized that the note had been written by none other than the young janitor from Yemen. Shalom the humble janitor was in fact a great talmid chacham! HaRav Shalom Sharabi ended up marrying Rav Gedalia’s daughter, and later took over as rosh yeshivah.

The Churva

Our last stop is the large square in the center of the Jewish Quarter. The white dome of the Churva shul dominates the view.

It’s called the Churva, which means destruction, or ruin, because it has a history of being destroyed. It was originally built in the 1700s by the talmidim of Rav Yehuda HaChassid, who had emigrated from Poland. Just a few years later, the Ottomans destroyed it, because the Jewish owners had failed to repay their debts to the Arabs. The ruin became known as the Churva. It lay desolate for 116 years, until the Perushim, who came from Lithuania, rebuilt it. It stood for less than 100 years, until it was destroyed yet again by the Jordanians in 1948. The shul was finally restored to its former glory in 2010.

Right next to the Churva is another shul called the Ramban shul. This was founded by the Ramban in 1267. It was built below street level because of a law that required all buildings to be lower than the mosques (the Muslim prayer buildings).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Jr., Issue 931)

Oops! We could not locate your form.