The Pachad Yitzchak

| December 18, 2019

U

nderstanding Rav Yitzchak Hutner (1906–1980) begins with understanding the role of misunderstanding. When originally circulated, his Torah, later known as Pachad Yitzchak, was only intended for those who were present when he spoke. Even now in subsequent printings there is a reminder that the style and structure of Pachad Yitzchak still mirrors the original delivery in front of an intimate audience. I’ve always wondered why this style was preserved even after his seforim were published for the masses. Why not have a more classic collection of essays, instead of preserving the original spoken format? But maybe that’s the point. Rav Hutner’s Torah is not designed to be read. It’s meant to be experienced. Learning his seforim transports you to his beis medrash. The lights feel dimmer; you’re finding a rebbi. And I think that’s why there is a healthy protectiveness among his talmidim and in the introduction to his seforim — there is room to misunderstand Rav Hutner because his Torah is written in such an idiosyncratic way. Rav Hutner, whose 39th yahrtzeit is on 20 Kislev, is still speaking to you.

The Yeshivish One-Liner

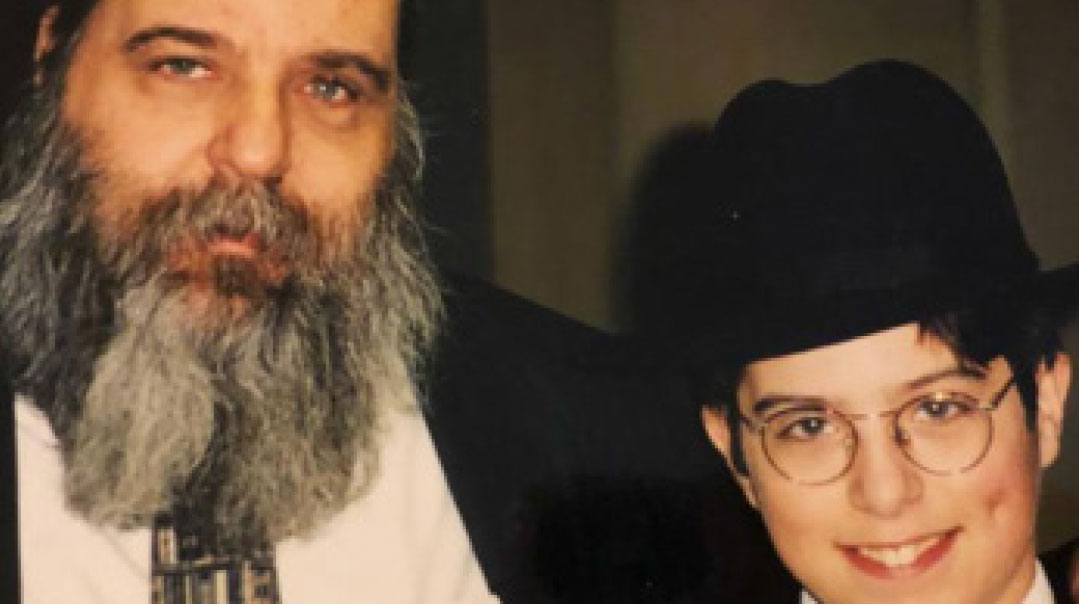

The first time I ever heard the name Rav Hutner I think I was in seventh grade. My menahel, Rav Chanina Herzberg a”h, used to quote Rav Hutner. It was his rebbi’s rebbi — Rabbi Herzberg studied under Rav Shlomo Freifeld. They all even looked alike. But here’s the thing: I don’t remember anything Rabbi Herzberg mentioned in his name. I only remember how those citations would make me feel. They were funny. Seventh graders usually only laugh at things that are silly or immature. But the first time I heard a “one-liner” quoted in Rav Hunter’s name it was laughter mixed with awe. I discovered humor that emerged from brilliance rather than childishness. Some will likely find this introduction to Rav Hutner to be infantile itself. I don’t think so. There’s a reason so many of the great one-liners in yeshivah lore are cited in his name. In fact, the second letter in Rav Hutner’s Iggros U’Kesuvim Pachad Yitzchak highlights the significance of playfulness in Torah. As opposed to the rigor of halachic analysis, there is a joy and creativity that emerges in this playfulness. On his deathbed, a nurse asked if he was comfortable (“Hai’im noach lo?”). Rav Hutner responded, “They asked me if it’s Noach and I have just about reached Lech Lecha.” His letters are filled with brilliant imagery and cunning analogies. Taking your spiritual pulse during times of difficulty is like a beis din judging at night (no. 96); evaluating spiritual strength while in yeshivah is like trying to figure out how much water is in a boiling pot (no. 97); getting advice in today’s modern world is like following the waves of a boat rather than footprints in the sand (no. 100). It’s hard not to smile. Each of his letters are like those old magic-eye images. Learn them long enough and a 3D image begins to appear. It’s not just Rav Hutner’s words that appear on the page — he appears before you.

Becoming Broad

One of the toughest decisions I ever made was leaving Ner Israel to study in Yeshiva University. I loved Ner Israel and my rebbeim there, but I decided to leave for a very unusual reason. I wanted to study under Dr. Yaakov Elman. While he looked rabbinic, he was immersed in a very different world — academic Jewish studies. He also had a personal relationship with Rav Hutner. I remember he once said to me, “I believe b’emunah shleimah that Rav Hutner had ruach hakodesh.” I was struck hearing this from someone so immersed in the world of academia. Surely, academics were trained to have more sober phraseology. But I think there was a specific ruach hakodesh that Rav Hutner embodied and imparted. In a well-known letter (no. 94), Rav Hutner reminds a student to live a broad life, rather than a double life. Some people look at their career, their interests, as living a double life — they have a secular home and a Jewish home. Instead, Rav Hutner insists, you need to build a large home with many rooms — a broad life. Rav Hutner helped his students to discover the ruach hakodesh hovering throughout their own lives. If you’ve ever read the introduction to Pachad Yitzchak, you’ll see a name thanked for assembling the sefer: Rabbi Yisrael Kirzner. Who was this man who got a rare thank you in each volume of Pachad Yiztchak? Was he a rav? A menahel? In fact, he is an economics professor at NYU who has been on the short list to win a Nobel Prize. I’m certain he is not happy I’m even mentioning him here — though we don’t know each other. But, on the inside of each of my volumes of Pachad Yitzchak was a reminder what being a big person is all about. It is multifaceted. It is complex without being contradictory. It is honest and human without being hypocritical. It’s a large house with multiple rooms — all suffused with ruach and kedushah.

Everyone’s Story

When I was about to start eighth grade, my father sat me down. “Dovid, we see you like getting into trouble, but it’s time to get serious — you’re becoming a bar mitzvah this year.” I left the room crying — my father’s key demographic for motivational speeches was not twelve-year-olds. But the reason I cried was because Yiddishkeit was really difficult for me. What was meant to feel inspirational felt suffocating. I wasn’t the kid who sat through shul easily, I was the one climbing through the bathroom windows to escape the youth director. Sure, I was bright — but I was also mischievous. I loved learning, but I loved other stuff too. By 12th grade, my religious schizophrenia had fully emerged. I was in the top shiur, but still involved in bottom-shiur behavior. On Tuesday nights my friends and I would learn in Shor Yoshuv. (Learning is a generous term. It was mostly Dougies and hanging out.) They set me up with a chavrusa, Shmuel Dov Kelemer. He smelled like cigarettes, but then we started learning and he showed me a letter from Rav Hutner (no. 128). It felt like it was addressed to me. Ever wonder why there is no proper English biography of Rav Hutner? Well, in this letter Rav Hutner makes it clear. He disdained biographies. They’re too neat, too sequential. Young genius becomes gadol hador, says Rav Hutner, glosses over the humanity and messiness that really animates the lives of gedolei Yisrael. Greatness does not emerge despite failure — it emerges because of their experience with failure. At so many points in my life I’ve said to myself, “now is when you’ll finally buckle down and get it right.” When I graduated high school I went to study in Sha'alvim. Finally, I told myself, I’ll become the model ben Torah that has eluded me. But it didn’t happen there either. Instead, Rav Ari Waxman, Sha'alvim’s mashgiach, reintroduced me to Rav Hutner. He taught Pachad Yitzchak every Monday night, and for the first time, I felt a resilience to be stretched, shaped, and challenged. Pachad Yitzchak presents a Yiddishkeit of evolution, change, setbacks, and disappointment. And Rav Hutner taught me to approach my own story the same way.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 790)

Oops! We could not locate your form.