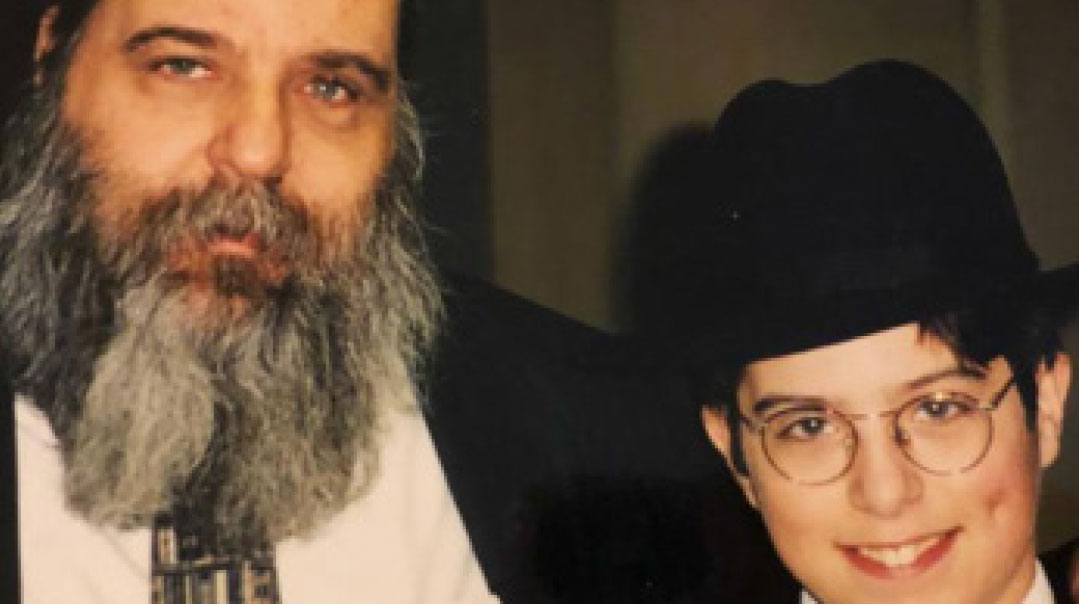

Rabbi Herzberg

| December 26, 2018

I

attended South Shore elementary school in Hewlett, New York, from 1990 through 1998. Throughout my years there my menahel was Rabbi Chanina Herzberg, who passed away this past week. The following are lessons from his presence in my life.

The lokshen is always at the bottom.

There were two types of moments you could have with Rabbi Herzberg — one in his office and one after winning a raffle. The former was terrifying, the latter was exhilarating. When Rabbi Herzberg officiated — and there is no other appropriate term to describe the way he conducted a raffle — it was like he was the mesader kiddushin at a wedding. There was gravitas and anticipation as he picked out the lucky name who would win a few dollars (I think two dollars) or a soda. Rabbi Herzberg used his own black hat as the receptacle for the tickets, and as he pulled out the name, it’s how I imagined it looked when Abraham Lincoln pulled out the Gettysburg address from his top hat. But before pulling out a name, he would mix up the tickets and always say the same line: “The lokshen is always at the bottom.” He reminded us that, like with a hearty bowl of chicken soup, the good stuff was at the bottom of the hat.

That, however, wasn’t the only place he used the phrase. Walking into Rabbi Herzberg’s office was nothing short of harrowing. He would sit behind his desk, sleeves rolled up, imposing elbows planted on his desk. But once the door shut, Rabbi Herzberg balanced rebuke with warmth. It was always clear, to me at least, that he enjoyed the students who were a little wilder and jumpier. A student who was sincere and struggling wasn’t a problem or an issue — it was the lokshen at the bottom, waiting to be discovered.

The Gold Medal is Tefillin.

There was nothing that elicited stronger intervention from Rabbi Herzberg than students bullying one another. I know this because I was the recipient of such an intervention. In fifth grade, my group of friends somehow became known as the “Lawrence gang,” and Rabbi Herzberg wouldn’t have such a clique. Like a New York City mayor, he began integrating members of the alleged gang, and made it clear that such social structures would not have a place in the Yeshiva of South Shore. When Rabbi Herzberg spoke about bullies, he would always repeat the story about a boy in his own childhood class. The boy was overweight and the boys would tease him, calling him “Blimpie.” Eventually, after constant ridicule, Blimpie left the Jewish community. This was the cautionary tale Rabbi Herzberg would repeat to ensure that no such bullying occurred under his auspices.

Rabbi Herzberg didn’t just spend his time breaking up bullies, he built up students to make sure they never felt diminished. The most memorable moment for so many South Shore students was Rabbi Herzberg’s practice of changing from his Rashi tefillin to his Rabbeinu Tam tefillin. It wasn’t his wearing two pairs of tefillin that interested us as much as his custom of giving his tefillin to one of the boys to wrap. He took off his tefillin to a crowd of outstretched sixth-grade hands that looked like a flock of seagulls waiting to be thrown bread. He would pick a different boy every day and when you got chosen, it felt like you won an Olympic gold medal. In Rabbi Herzberg’s school, the best deterrent to bullying was to make everyone feel like a winner.

Charlie, do you want to learn?

I still haven’t figured out if the students of Rav Hutner started to look like him or if it was just that the type of student who was attracted to Rav Hutner also kind of resembled him. Aside from bearing an uncanny resemblance to Rav Hutner, Rabbi Herzberg continued his legacy of chinuch. Beginning as a student of Rav Hutner and later with Rav Hutner’s own talmid Rav Shlomo Freifeld at Sh’or Yoshuv, Rabbi Herzberg escorted chinuch tradition into a new millennium.

When Rabbi Herzberg first applied for admission to Rabeinu Chaim Berlin, he sat with Rav Hutner and, obviously nervous, stammered a bit before reading. Rav Hutner quickly interjected, “Hey, Charlie, do you want to learn Torah?” It was the answer to that question that Rav Hutner cared about, not how skilled of a leining Rabbi Herzberg could make. Even during my time in South Shore, Rabbi Herzberg would often call me Charlie (it was Rabbi Herzberg's English nickname). It wasn’t my name, but I like to think it was his way of reaching back to that moment with his rebbi. Rabbi Herzberg would look at us the same way Rav Hutner looked at him: Charlie, do you want to learn? It was the answer to that question that mattered most to him.

(Excerpted from Mishpacha, Issue 741)

Oops! We could not locate your form.