The Moment: Issue 1067

| June 24, 2025It wasn’t just the miracle that radiated Divinity

Living Higher

T

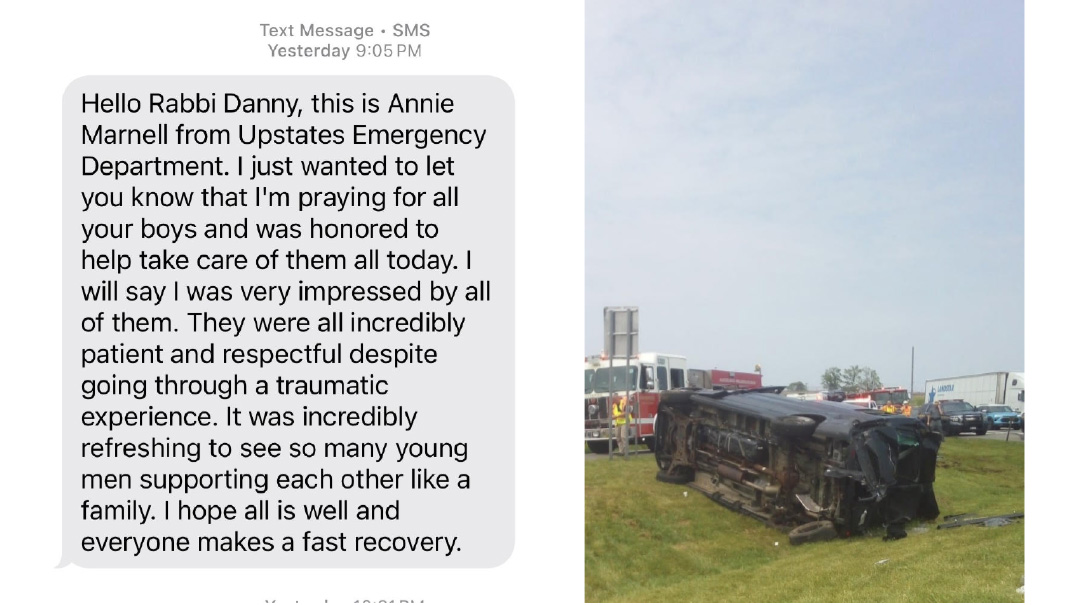

wo weeks ago, a terrifying accident evolved into an open miracle, and a great kiddush Hashem. A group of boys from the Yeshiva of Rochester’s 11th and 12th grades were en route to a whitewater rafting trip when they were hit by an 18-wheeler truck. The 15-seater van rolled off the highway, turning over a few times before coming to a stop on its side. Miraculously, no one was seriously hurt. The passengers were all taken by ambulance to a hospital in Syracuse. Further examination revealed a few concussions, but no major injury. It was a true neis.

But apparently, it wasn’t just the miracle that radiated Divinity. The boys themselves also carried the banner of sanctity. Rabbi Chaim Dov (Danny) Goldstein, the yeshivah’s executive director and general studies principal, received a text from the nurse who had tended to the talmidim.

Hello Rabbi Danny, this is Annie Marnell from Upstate’s Emergency Department. I just wanted to let you know that I’m praying for all your boys and was honored to help take care of them all today. I will say I was very impressed by all of them. They were all incredibly patient and respectful despite going through a traumatic experience. It was incredibly refreshing to see so many young men supporting each other like a family. I hope all is well and everyone makes a fast recovery.

Mission Control

By Sandy Eller

IN

these terrifying, confusing, Divine times, inspiration radiates from so many corners of life. Our meticulously drawn plans for a summer vacation in Eretz Yisrael have evaporated, replaced by the keenly felt knowledge that at this hour of historic transformation, you will be exactly where He wants you to be.

We look to the news and see horror, but almost blinding the darkness is the stunning light of constant miracles.

These are otherworldly times indeed.

For so many, their stories began the moment they received notice that no flights were entering or leaving Israeli airspace. An ocean stood vast and defiant, separating mothers from children, husbands from wives, children from parents; there was simply no way out.

In a move whose irony laced through current affairs with an air of historical paradox, throngs began flocking from Israel — toward Egypt. Others found exit through Jordan; yet others through Cyprus.

Each journey comes with a story.

For Rabbi Yeruchim Silber, Agudath Israel of America’s director of New York government relations, making it home in time for his grandson’s bar mitzvah was a journey that spanned five countries and nearly two full days.

Like so many others in Israel on June 13, Rabbi Silber was awakened at 3 a.m. as chaos erupted. Hearing someone pounding on his door and shouting for him to wake up, he raced downstairs to a safe room where everyone was talking about an attack. His phone blew up with messages as family members in New York reached out to make sure he was okay.

By Sunday morning, Rabbi Silber knew that he needed to start making arrangements if he wanted to be at the upcoming simchah. It was obvious that no one had clear information and that there were definitely those looking to make a quick buck from stranded travelers.

Researching flights, Rabbi Silber quickly ruled out the $2,000 tickets from Zurich to New York, opting for the more scenic but affordable route.

Rabbi Silber reserved a spot in a van to Egypt with a Reb Arele chassid named Motti who had plenty of experience taking people through border control. Next, he booked a flight from Sharm El-Sheikh to Zurich with a stop in Cairo, and another from Zurich to JFK, with a quick stop in the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik.

By Tuesday morning at 11 a.m., Rabbi Silber was ready to roll, armed with a wad of cash for the assorted tips and fees he knew would be coming, and two days’ worth of food. The first leg of his trip took approximately four and a half hours, and despite the long lines and hot weather, getting through Israeli border patrol at Taba was straightforward — show your passport, pay an exit fee of about $15, and cross under a LED sign whose red lights spelled out Egypt in Hebrew and in English.

Clearing Egyptian border patrol was slightly more complicated and definitely more stressful. Rabbi Silber was grateful for Motti’s presence. It was unclear who could be trusted and obvious that there were those who saw the travelers from Israel as easy targets for making a quick buck. There were multiple fees — approximately $15 for a transit fee and another $50 for visas, procured by someone who insisted on being tipped for his services.

After finally emerging from the Israeli-Egyptian border two hours after arriving in Taba, Rabbi Silber and his group were met by Suleiman, an Egyptian driver who often works with Motti. The full impact of being in Egypt hit Rabbi Silber at that moment, and he was grateful to have made reliable arrangements in advance, instead of relying on the taxis of questionable origin waiting to pick up fares.

Suleiman showed a list with the names and passport numbers of his passengers at the multiple checkpoints they encountered during the first few miles of the trip from Taba to Sharm El-Sheikh, with the remainder of the 134-mile trip along the eastern edge of the Sinai desert to the Red Sea passing uneventfully. After spending the night at a hotel, Rabbi Silber headed to the airport, noting the separate men’s and women’s security lines with interest, although airport security insisted that he delete the videos he took.

Rabbi Silber spent nearly 16 hours in the air getting back to New York, but the four legs of his trip were blissfully smooth. A flight attendant on his trip to Zurich apologized for not having kosher meals, and he had an entire row to himself on his plane to Reykjavik. Ironically, the only delay he experienced was at JFK, with congestion on the tarmac resulting in a 45-minute delay getting to the gate.

Rabbi Silber bentshed Gomel the morning after his return, and he has some advice to those still trying to get home. Do your due diligence. Avoid anyone who insists on being paid by Zelle. Stay within the secure area in foreign airports. And say Tefillas Haderech with extra kavanah.

Upon returning home, he fielded numerous questions from the grandchildren. What does a Mitzri look like? How could you go to Egypt when we learned that you’re not supposed to go there?

He didn’t have much to offer to the many who wanted to know what Egypt looked like, as all he’d seen was the desert, the hotel, and the airport.

The cost of getting home? About $1,700 (including the cost of two sets of plane tickets, ground transportation, fees, and the hotel stay). Being able to attend a grandson’s bar mitzvah? Priceless.

A

mid clouds of fear and confusion, the flashes of Divine Providence are standing out starkly. Here’s another one.

Lakewood resident Yehuda Gelman was busy last week trying to make travel arrangements out of Israel, not for himself but for others. As the founder of Highway of Hope, an organization that helps people with rare diseases and physical disabilities live more independently, Yehuda was involved with several families whose tickets out of Israel were canceled. One of them was a nonobservant Jewish family whose ten-year-old son Jake* had been born with an extremely uncommon medical condition.

There are only 170 people in the world with Jake’s condition, and several of Yehuda’s patients had been treated successfully for it by Dr. Malcolm Byrnell*, who practices in France and Germany. As the world’s leading expert in this condition, Dr. Byrnell was highly sought after, and so far, Yehuda’s years of effort to get the doctor to take on Jake’s case had been fruitless.

Jake and his family were scheduled to wrap up a visit to Israel on the morning of June 12, but their plans were delayed when Jake suffered a small medical episode while they were already in Ben-Gurion Airport. By the time Jake was cleared to fly, Israel’s skies had been closed and they reached out to Yehuda for help getting home. Arrangements were made for Jake, his family, and several other of Yehuda’s patients to take a boat to Cyprus where they could catch a flight back to New York.

The story should have ended there, but it didn’t. While all this was going on, Yehuda was checking out upcoming clinical trials and he reached out to Dr. Byrnell to see if they could set up a time to speak. In response, he received an email telling him that Dr. Byrnell was not available, as he was taking his first vacation in over two decades.

He was currently in Cyprus.

And so Yehuda asked Dr. Byrnell’s office staff to find out if the doctor could spare just five minutes of his time for Jake, without taking any responsibility for his care.

He replied that he would. The meeting was arranged and not only did Dr. Byrnell wind up agreeing to take on his case, he also gave him two doses of medication his wife had brought along for a condition of her own that is also used as an off-label treatment for Jake’s condition. Then he told the parents to make arrangements to see him again in Germany.

Jake’s parents observed Shabbos this past week. Because they openly saw the One Who commanded us to do so. And soon, the whole world will see Him as well.

*names have been changed

Be Smart

Logistics for these trips requires more than efficient packing. Cultural sensitivity and a few doses of common sense are well in order.

Amudim’s David Kushner has some practical advice for those looking to travel through Amman or Aqaba as they make their way to or from Israel.

While for more than a decade Jordan has had policies in place that didn’t allow people to bring tefillin into the country, temporary arrangements have been made to relax that rule. Still, Kushner warns travelers to put their tefillin inside their suitcases instead of showing up at the border with their tefillin in hand, to minimize the chance of them being confiscated.

“For years, border agents were trained not to let tefillin in,” says Kushner. “So while a memo might have gone out allowing them for now, don’t shove it in border patrol’s faces.”

Similarly, Kushner cautions against making minyanim at the border, being combative, or taking pictures or video of border agents.

“They don’t like that and you need to be seicheldig,” says Kushner. “Just because you put on a baseball cap doesn’t mean you don’t look Jewish.”

While he knows it isn’t easy, Kushner has been urging people to stay where they are for now, as those with urgent needs are prioritized and moved to the top of the lists. The situation changes not just daily, but hourly, and sometimes even by the minute, as plans for evacuation flights are being worked out. Amudim has been working hand in hand with the Agudah, Chaim V’Chessed, Eretz Hakodesh, and Ichud Yeshivos to facilitate travel for the many stranded travelers.

“We collaborate and share information in real time, and we do that daily, sometimes even on an hourly basis,” says Kushner. “We’re all putting our heads together and dealing with challenges.”

The Sweetest Revenge

By Yisrael Yoskowitz Krakow, Poland

I

t’s Monday morning, at the end of May, when a three-hour flight from Israel brings us to Krakow’s international airport, named after Pope John Paul II.

The name evokes a sense of unease in me, not only because of what it represents, but also because of a personal reckoning dating back to somewhere in the late 1990s. My grandfather, Rabbi Pinchas Menachem Yoskowitz ztz”l, was serving as the Chief Rabbi of Poland then, and he bore a weighty responsibility: preserving the concentration and extermination camps and what remained of Jewish life in a country that was once the spiritual center of Europe.

One day, the Carmelite monastery placed 50 crosses throughout Auschwitz. My grandfather, a survivor of the camp, was horrified. When John Paul came to visit Warsaw, a brief meeting was arranged between them. My grandfather addressed him and requested that the crosses be removed. The pope, in turn, refused. “This is a holy place,” he said, “and as such, it deserves holy symbols.”

My grandfather stood his ground. “This ground is soaked with the blood of millions of Jewish martyrs,” he replied. “Its sanctity requires no additional symbols — neither Jewish, Catholic, nor Muslim.”

The exchange lasted perhaps two minutes. Tension was evident on the faces of those present, including dozens of bishops who stood by, stunned at the Jewish rabbi’s chutzpah. The next day, newspapers in Poland and around the world reported the confrontation between the rabbi and the pope. Ultimately, the monastery backed down and the crosses were removed, but my grandfather paid a heavy personal price: Incitement against him in Poland intensified, and he was forced to resign.

Fourteen years have passed since his passing. If only I could tell him what has happened since: of the communities that have been rebuilt, the voice of Torah once again echoes in places where there was only bloody silence, and of the unimaginable growth of communal and religious infrastructure.

O

ver 80 years after the Auschwitz-Birkenau camps began operating as an industrial murder facility, I walk those grounds same ground as part of a delegation from the Rabbinical Center of Europe, composed of hundreds of emissaries, rabbis, and representatives of distinguished communities, living proof that the Jewish spirit cannot be extinguished.

Leading the delegation is Chief Rabbi of Israel Rabbi Kalman Bar, and Rishon L’Tzion Rav Yitzchak Yosef.

This year, the RCE marks a quarter-century of groundbreaking activity; 25 years of building communities, establishing spiritual leadership, and fostering Jewish life precisely in the places our oppressors tried so hard to obliterate it.

Over the years, it’s become a spiritual anchor for hundreds of communities. Quietly, through painstaking effort, its leaders have succeeded in uniting community rabbis under one roof and serving as a supportive address for their day-to-day needs.

As I see it, European Jewry owes its remarkable revival to the rabbis and leaders of the RCE.

This year’s conference was held at the Hilton Hotel in Krakow, and was attended by hundreds of remarkable figures who play significant roles in Jewish life across Europe. The guests include figures like Rabbi Teichtal from Berlin, Rabbi Segal from Baku, and Rabbi Biderman from Vienna — men who oversee massive operations of Torah, education, charity, and kindness. They’re all fueled by one thing: the awareness that if they don’t do it, no one else will.

IN

the hotel lobby, I meet Rabbi Aryeh Goldberg, the RCE’s CEO.

“Twenty-five years,” he tells me, “is an especially emotional milestone.”

“Why?” I ask.

“If you only knew what we went through to get to where we are, you wouldn’t ask,” he replies.

“Tell me more about what you do,” I ask him.

“It boils down in three central goals,” he says. “Strengthen, connect, protect. Over the years, we’ve built nearly a hundred mikvaos across the continent, established chesed centers that operate around the clock, and founded dozens of religious institutions.”

He tells me about the ongoing work with the participating rabbis: “Hundreds of seminars, conferences, and professional and Torah-based training sessions. We help them stay current, stay connected, and get support when needed.”

I ask him to elaborate about what he means when he mentions protection as one of the organization’s primary goals.

“We fight daily against anti-Jewish — especially anti-religious — legislation in various countries,” he explains. “We maintain direct contact with governments, parliaments, and regulatory bodies to ensure the rights of European Jewry.

“Our goal is simple,” he concludes. “We want to ensure that Jewish communities can thrive without fear of those who want to limit our freedom.”

He describes the wide range of attendees, more than 250 rabbis from across the spectrum — chassidim and Litvaks, Sephardim and Ashkenazim, Chabadniks and community rabbis.

“This diversity isn’t just decorative,” Goldberg emphasizes. “It’s the strongest proof that the Center is succeeding in connecting everyone standing on the frontlines of the battle for Europe’s Jewish identity.”

“This is not just a celebration of twenty-five years,” one rabbi tells me. “It’s a declaration of intent for the next twenty-five years.”

IN

a long convoy of buses, we set out together to the Auschwitz and Birkenau extermination camps.

A silent procession of hundreds of rabbis makes its way solemnly through the pathways of this mute memorial. There’s the kind of thunderous silence you only hear in such places, behind which you can almost hear the cries of a mourning mother, the screams of children torn from their parents.

In one of the buildings hangs a haunting photo in which a group of Jews stands at the crossroads between life and death, a Nazi beast’s finger pointing their fate — the labor camp or the gas chambers.

Rabbi Kalman Bar approaches me. “My parents were survivors of the camps,” the chief rabbi of Israel tells me. “When I come to Poland, I always feel very mixed emotions. On one hand, this is my family’s history; on the other, there’s the deep pain over the terrible tragedy. My father’s entire family was annihilated here.”

“I’m a third-generation survivor,” I tell the rabbi. “I was very close to my grandfather, who didn’t spare any details about what happened there. In your home, did they speak about the Holocaust?”

“My father refused to speak about Poland,” Rabbi Bar says. “His silence accompanied me throughout my childhood. My mother, on the other hand, shared more. Her parents — descendants of the Ruzhin dynasty — miraculously made it to Israel, but the entire extended family stayed behind. They didn’t survive.”

I asked the rabbi how he feels now, stepping onto this cursed soil as the chief rabbi of the Jewish state, escorted by police vans and a special motorcycle unit wherever he goes.

“The external symbols don’t matter much to me,” he says. “But when I remember the intentions of the beasts who operated here — to destroy, to obliterate, to erase the memory of the Jewish people — there’s no doubt this is a moment of sweet revenge.

“I, the grandson of Holocaust survivors who stared death in the face and were saved by a miracle, return here not as a refugee, but as the chief rabbi of the State of Israel, proudly bearing the voice of a people that did not surrender.”

After about an hour, maybe a bit more, we continue on to the nearby Birkenau camp. At its entrance, hundreds of rabbis gather, led by Rabbi Kalman Bar and Rav Yitzchak Yosef. As they walk along the train tracks upon which Jews from across Europe had been transported to their deaths, they break out in emotional song.

At the end of the walk, after the recital of Keil Malei Rachamim, Rabbi Bar speaks. “When we talk about commemoration, we mean continuing what was cut short. For us, commemoration is not just a plaque or a monument. True commemoration is to reestablish the great Torah scholars and Jewish leaders, the rabbis and their students who were so cruelly uprooted here. That is our mission: to empower the Torah world with renewed strength and resolve.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1067)

Oops! We could not locate your form.