The Mind Behind the Madness

| February 27, 2024The problem is, most of the time we don’t understand the math and science of other people’s behaviors

The Mind Behind the Madness

Shoshana Schwartz

IF

you place a hard object inside a solid container and shake, you know it’s going to make noise. Even without conscious thought, you understand that sound is being created and that your ears are transmitting that sound to your brain, where it is processed. Assuming you’ve been blessed with the ability to hear for many years, this will be utterly unsurprising.

If you demonstrate this action to a baby, though, she’ll be enchanted with the resulting sound long after your adult ears tire of it. To her, the noise is a new and exciting experience. It seems magical to her, the same way most adults would find the Northern Lights, the pull of the tide, or communication between bees. If you’ve studied these phenomena and understand the math and science behind them, you might be even more in awe of the intricacies of Creation — and, by extension, the Creator — but you would certainly be less surprised.

The same is true for human behavior.

People act the way they do for various reasons. When you know the “math and science” behind their behavior, it’s much easier not to judge them or take their actions personally. Imagine a rambunctious preschooler whose mother has been hospitalized for the past few months. You might cluck your tongue in sympathy and concern seeing him act out, but you won’t criticize.

The problem is, most of the time we don’t understand the math and science of other people’s behaviors. It’s challenging to accept the tantruming toddler, the rebellious teenager, or the obnoxious adult, especially if you’re in the line of fire.

Fortunately, we don’t have to understand the math and science — i.e., the reason for the behavior. All we need to understand is that there is a reason, and we just don’t know what that reason is. When we see others act in a way that seems inappropriate, wrong, bad, mean, or selfish, we can remind ourselves that there’s an unseen reason, and that if we knew that reason, it would all suddenly make sense.

While this may sound relatively simple on paper, the truth is that implementing it requires a hefty dose of humility, which can be really difficult to access when we’re feeling confused or hurt by others’ actions. Seeing it as “math and science,” realizing there’s an equation written in obscure symbols on a hidden whiteboard, can help depersonalize the hurt, making it easier to stay humble; it can remind us that there’s logic here that is gibberish to a layperson. (Of course, acknowledging that you don’t know someone’s reasons doesn’t mean you agree with their actions, nor do you need to allow yourself to be treated disrespectfully.)

There’s one instance, however, that requires extra caution when applying this tool: using it on ourselves. Imagine telling yourself, “I had an unhappy life, it’s no wonder I’m so mean to everyone.” We do want to embark on a gentle, compassionate search for what drives us to act imperfectly, so we can repair or reparent ourselves. We don’t want to justify our questionable actions by blaming the people or situations that helped write our own equations. We do want to be patient and understanding as we make small, incremental progress. We don’t want to develop an attitude of “Poor me!”

Conceptualizing people’s reasons as the math and science behind their decisions can help us judge people favorably, reduce conflict, and develop humility.

Shoshana Schwartz specializes in compulsive eating, codependency, and addictive behaviors.

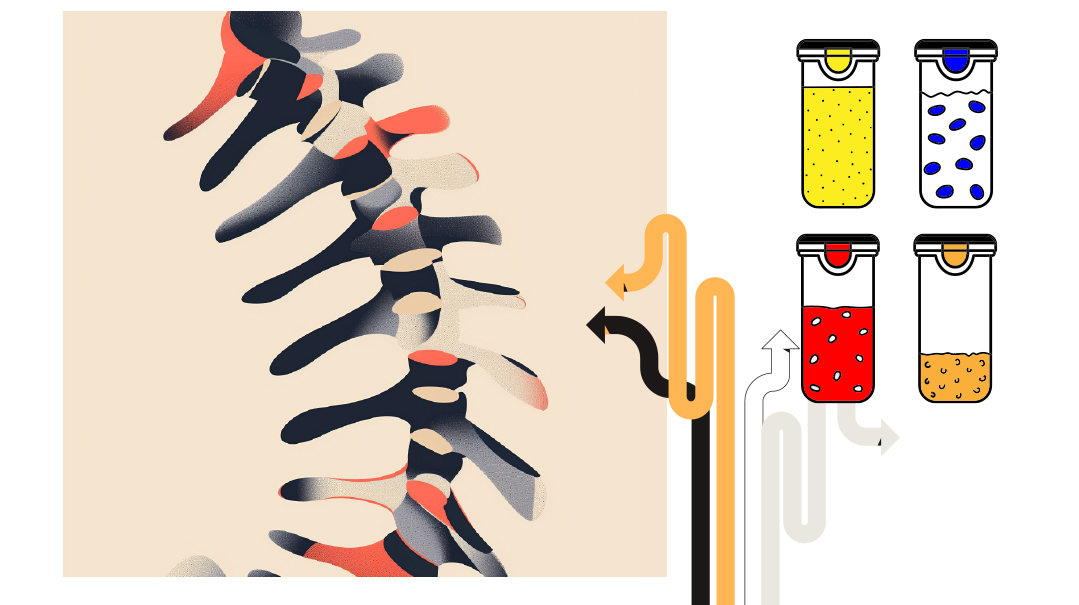

Identifying CH

Dr. Jennie Berkovich

T

he first 24 to 48 hours of a newborn’s life are a whirlwind of vital interventions and screenings aimed at ensuring a healthy start to life. Amid the flurry of activity, one crucial test screens for congenital hypothyroidism (CH). This heel-prick test, conducted within the initial days postpartum, is done in most states as part of the newborn metabolic screen.

In the beginning, congenital hypothyroidism manifests subtly. Newborns with CH may exhibit symptoms such as poor feeding, excessive sleepiness, a weak or hoarse cry, constipation, and prolonged jaundice. Macroglossia (an enlarged tongue) may emerge as a later, distinctive feature.

If the metabolic screen comes back abnormal, the results are immediately shared with the baby’s pediatrician. In such cases, a geneticist or endocrinologist works with the pediatrician to determine the next steps, often confirmatory tests with repeat bloodwork.

Prompt intervention following a positive CH screen is important and time sensitive. Levothyroxine, a synthetic thyroid hormone, is the gold standard for treatment, with dosage tailored to the severity of the hypothyroidism. Follow-up visits are frequent at first, as the dose may need to be adjusted based on the infant’s response and subsequent blood tests.

Untreated hypothyroidism can lead to intellectual disability, growth retardation, and delayed development. However, with timely and appropriate intervention, infants diagnosed with hypothyroidism go on to lead normal and healthy lives. While a significant portion of infants may outgrow the condition, some may require lifelong medication.

In contrast to CH, acquired hypothyroidism is a condition that develops in older kids and not infants. This, too, is typically treated with levothyroxine and generally has an outstanding prognosis.

Dr. Jennie Berkovich is a board-certified pediatrician in Chicago and serves as the Director of Education for the Jewish Orthodox Medical Association (JOWMA)

Respect and Suspect

Sarah Rivkah Kohn

When we are hurt by someone who has hurt us before, we may be quick to assume that the question, comment, or behavior was intended to hurt us yet again.

Our body and mind may even tell us that this innate suspicion is a wonderful thing. In reality, though, we’re harming ourselves.

Many years ago, a rav shared with me the Torah’s formula to live happy, healthy, and productive lives: “Kabdeihu v’chashdeihu — respect him and suspect him.” In situations where we’re unsure of another’s intentions, we need to be careful and take precautions.

But, he pointed out, the Torah does not use the opposite order: suspect and then respect. This is because our lives are meant to be lived assuming ignorance, not malice. We need to assume most of the world is good, while of course still protecting ourselves from people who arouse suspicion. But living a life where most are suspect and very few, if any, can be trusted, can make for a sad and dysfunctional life.

Sarah Rivkah Kohn is the founder and director of Links Family, an organization servicing children and teens who lost a parent.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 883)

Oops! We could not locate your form.