The Lie I Lived with

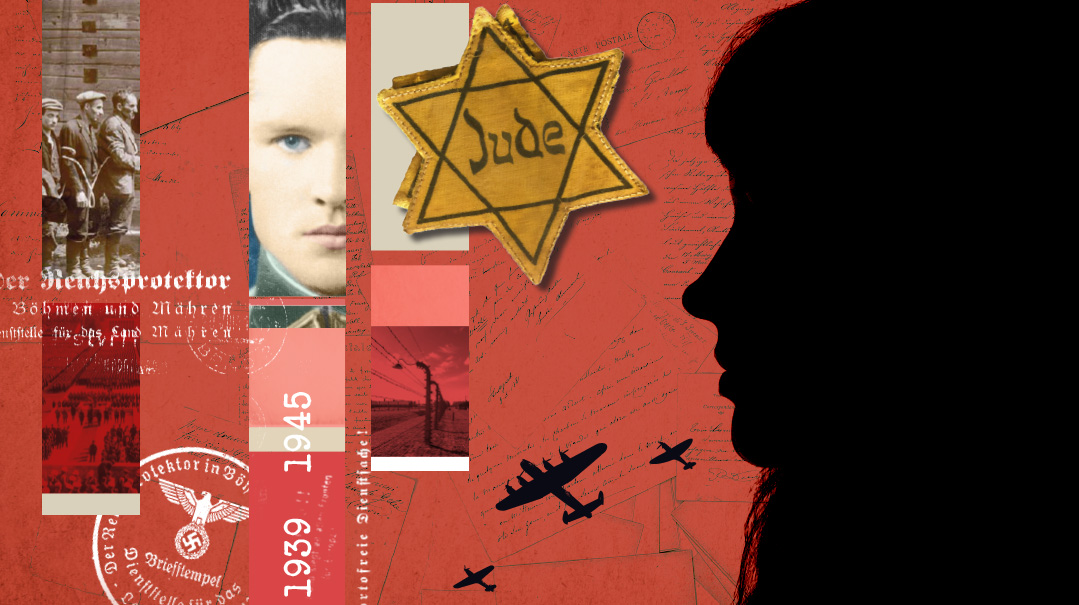

She thought her grandfather was a hero. Then she learned he was a Nazi

Photos: Silvia Foti archives

Growing up in the 1960s in Chicago’s Marquette Park neighborhood, which boasted the largest population of ex-pat Lithuanians outside their homeland,

Silvia Foti was raised on the story of her heroic grandfather, a warrior for Lithuania’s freedom during World War II who died a martyr’s death at the hands of the country's Soviet conquerors. According to family and local lore — and even the Lithuanian government, who honored him with plaques, street names and a school — Jonas Norieka was a hero who paid the highest price for his ideals. He fought the Nazis when they occupied the country early in the war, was sent to a concentration camp, rebelled against the subsequent Communist occupation, and was then thrown into a prison of the NKVD (the precursor to the KGB) for treason, where, at age 36, he was tortured and murdered in 1947.

Silvia, a 61-year-old high school literature teacher in Chicago and a former journalist, says she felt like the coddled princess of the tight-knit community, growing up as the granddaughter of a hero who had resisted the Nazis, had paid with his life for bravely battling the Communists.

For years, Silvia’s Lithuanian-born mother, who was just seven years old when her venerated father was tortured and killed by the NKVD, had devoted herself to gathering material for what was to be a national tribute to him. She’d collected thousands of pages of NKVD and KGB transcripts, letters he wrote to her mother (Norieka’s young wife), and hundreds of other related articles and documents. She even went back to university at age 55 and got a doctorate in literature in order to be better qualified to write her book. But she fell ill, and five years later, in February of 2000, she was on her deathbed.

“My mom was dying, she could barely talk, yet she pulled me close, took my hand and whispered, ‘Silvia, you have to write the book, you must write the story — everyone expects it.’ It was more like a command, and I knew I’d have to take it on, even though I didn’t believe I had the skills to master such a project. I was a journalist, but I’d never attempted anything like this. The sheer volume of the material she had amassed made it seem insurmountable,” Silvia tells Mishpacha.

Little did she know that honoring her mother’s dying wish would upend her life and shake the foundations of everything she knew to be true. Because over the next two decades, she would discover that although her grandfather was indeed a devoted Lithuanian patriot who wanted to see his beloved country independent, Jonas Norieka — whose nom de guerre was “General Storm” during the anti-Communist revolt — was also a rabid Jew-hater and Nazi collaborator who was directly responsible for the murder of close to 15,000 Lithuanian Jews in three towns that he’d personally made Junenrein as a district commander, in advance of the Nazi takeover.

Overwhelming as it was to continue her mother’s years-long project, Silvia began fulfilling her promise right after her mother’s passing. She’d brought most of the archival material her mother had collected to her house and was set to start on organizing it all, when her grandmother — Jonas Norieka’s widow for over half a century, who was also quite ill with a heart condition — took a turn for the worse.

“It was just five months after my mother died, and my grandmother was in the throes of death as well. Before she died, she called me over to her. ‘Silvi, how’s the book coming?’ she asked. I told her I’d collected most of the material when she surprised me and said, ‘Silvi, don’t write the book. Just let history lie. There’s no need to dig around.’

“I was stunned. ‘But I promised Mom!’ She just rolled over and faced the wall, and a few days later she was gone,” Silvia relates. “At the time, I thought she was just trying to protect me from the impossible promise my mom dragged out of me — that she didn’t want me to have the headache or the stress, because Mom herself had been so stressed out about it. Years later, after I came to painful terms with my irrefutable research, I realized that she must have known the truth all along.”

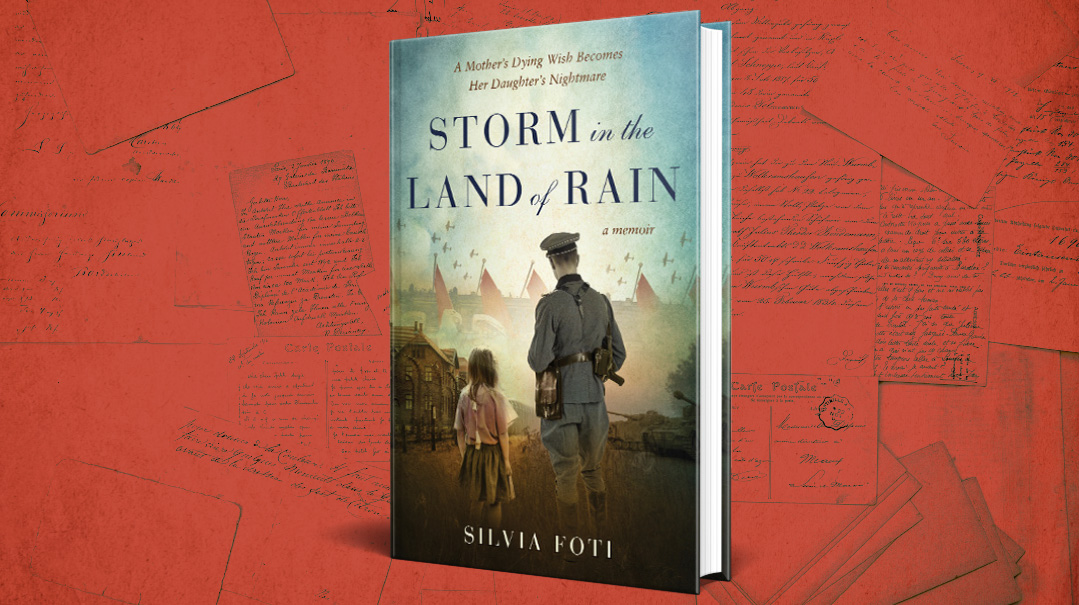

When her mother extracted a deathbed promise, Silvia thought she’d be writing a book about a hero and make her countrymen proud. But sifting through the archives and piecing together clues, she soon began to realize, to her horror, that her grandfather had more blood on his hands than she could imagine. There were initial years of denial, then periods of hope-against-hope research to dispel the rumors, and finally, directed by her own moral compass and need for integrity, a coming to terms with the harsh truth. It wasn’t the book her mother was hoping for, but last year, Silvia Foti finally released The Nazi’s Granddaughter: How I Discovered My Grandfather Was a War Criminal. The paperback edition is being released this summer with a new cover and title: Storm in the Land of Rain: A Mother’s Dying Wish Becomes Her Daughter’s Nightmare.

“The book is essentially a personal account of my own story, about coming to terms with who my grandfather was,” Silvia explains. “But it’s also a journalistic investigation — I’ve spoken to hundreds of people and gone through thousands of documents — and it’s also a study in Lithuania’s own Holocaust distortion, how they’ve continued to glamorize evil by propagating the image of my grandfather and others as heroes and ignoring that they were also killers.”

It’s made Silvia Foti somewhat of an outcast among much of the Lithuanian community, but it’s also made her an unwitting heroine within the Jewish world, even though she had little contact with Jews before.

“To tell you the truth, I didn’t expect that at all,” she admits. “Actually, I thought the Jews would hate me as much as the Lithuanians would hate me — they were my grandfather’s victims. Yet there was such a rush of love and support from the Jews that it really heartened me and gave me the energy to move forward.”

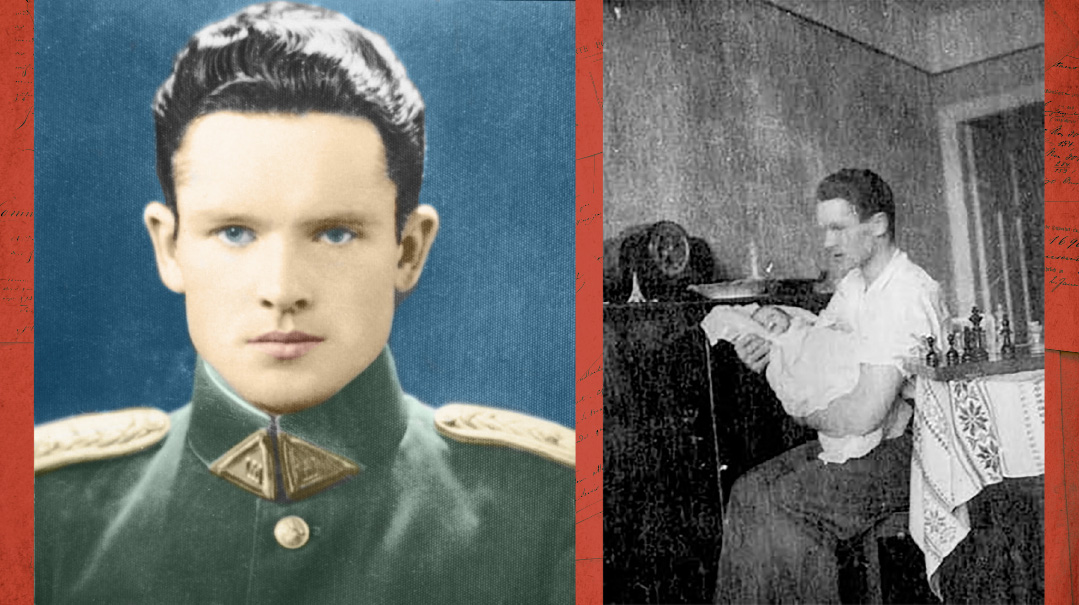

Jonas Norieka was handsome and charismatic, the stuff everyone wants their heroes to be made of (left); In calmer days, holding baby Dalia Maria, Silvia’s mother. Dalia was just four when her father would disappear from their lives forever

Who Was My Grandfather?

The first crack in Silvia’s perfect portrait of her grandfather, Jonas Norieka, came in October 2000, when she and her brother Ray honored the request of their mother and grandmother and went back to Lithuania to bury their remains. They were overwhelmed by the outpouring of affection at the funeral in the Vilnius Cathedral. Even independent Lithuania’s first president Vytautas Landsbergis and his wife attended, honoring the widow (Silvia’s grandmother Antanina Norieka), daughter (her mother Dalia Maria Kucenas) and grandchildren (Silvia and Ray) of Jonas Norieka, a.k.a. General Storm. When Silvia announced after the ceremony that she was planning on bringing her mother’s book to reality, the crowd embraced her. “You’re such a good daughter,” they said. “Our country needs heroes.”

After the funeral, Silvia and Ray were escorted to the Academy of Sciences, where, after the Nazi retreat and the Soviet takeover in 1945, Norieka had been a lawyer by day and underground resistance leader by night. A bronze plaque in his honor had recently been installed there. Next, they were brought as honorary guests to the town of their grandfather’s birth, where a grammar school was named after him.

“It was a beautiful reception,” Silvia recalls, “and then the director invited us into his office. He explained that until 1990, when the country gained independence from the Soviet Union, all the schools had Russian names, but the names were soon scrapped for local Lithuanian heroes. Then he pulled us to the side and whispered, ‘I got a lot of flak when we picked your grandfather’s name. You know, the Jews claim he was a Jew-killer. Anyway, it’s all in the past, and just a lot of Soviet propaganda. I’m getting more support than ever for choosing the name.’ ”

Silvia says that was the moment she lost her innocence concerning her grandfather. “It was traumatic for me, even though they said it was just a rumor. I was 38 years old, and had never even heard a hint of this rumor before.”

Back in Chicago, she confronted her father and others in the community: Did they ever hear this crazy story of Jonas Norieka killing Jews? “Yeah,” they said. “We heard it. Maybe it’s true, and maybe it’s just Communist propaganda. You know that Russia doesn’t want Lithuania to have any heroes who would instill national pride.”

“Well,” Silvia admits, “at the time that sounded good to me. So I became like the rest of them. I also went into denial — for about the next 10 years.”

But Silvia couldn’t completely ignore the rumors. She knew, for example, that her grandfather had been appointed by the invading Nazis as a district commander in 1941, the apex of his political career. But she never considered that, patriotic Lithuanian that he was, he might have also been a Nazi collaborator.

“When I first encountered the rumors, I felt like I was being ambushed,” Silvia reveals. “I was devastated, and totally unprepared, so I basically stayed away from the research. But then the journalist in me started taking over, and I told myself, you can’t ignore this, you need to look at this. So, then I went into the bargaining phase. I thought, maybe if I do start looking into this nasty period, I’ll be able to exonerate my grandfather. That was my plan. I was going to debunk the horrible rumors and bring Grandfather back to honor. The only problem was that once I started digging up the truth, I had to face it. There was no turning back after that.”

Silvia did another sweep of the archives — about 3,000 pages of NKVD and KGB documents and other transcripts her mother had collected and had translated into Lithuanian, dozens of letters Norieka had written to his wife and little daughter from prison, and a motley assortment of other documents.

“Most of the documents were in their Lithuanian original, which I read fluently, and Mom had the ones that were in German translated,” Silvia says. It was slow going, though, since at the time she was busy with work and raising two little children.

“There wasn’t much on the Nazi occupation, but then I came across a pamphlet my grandfather wrote in 1933, entitled Raise Your Head, Lithuania. It was essentially an anti-Semitic rant, calling for a Jewish boycott because the Jews are all thieves and cheats.

“It was so shameful, I just wanted to burn the thing, but I knew I couldn’t ignore it. Still, I justified that he was only 22 when he wrote it, and didn’t call for actually killing Jews, so I thought there was still hope to exonerate him. That was, until I came across another document, an order that he wrote while governor of the Siauliai district during the Nazi occupation, where he called for the rounding up of all Jews and half-Jews in the town and sending them to a ghetto — where three weeks later, on Yom Kippur, they were slaughtered.”

Meanwhile, Silvia — who has a master’s degree from Northwestern University School of Journalism and had been busy writing for others for two decades — decided to switch careers and become a teacher, so that she could have summers off to work on her own projects. She earned a second writing degree in creative nonfiction, and it was her program mentors who gave her the courage to come to terms with her research honestly without getting dragged into politically correct spins.

And so, with the encouragement of her professors, in the summer of 2013 Silvia traveled to Lithuania to do her own primary research. She hired a Holocaust guide named Simon Dovidavicius, director of Sugihara House, a museum honoring the famed Japanese consul to Lithuania who helped thousands of Jews escape through Japan at the beginning of the war.

“Most of the people who engage Simon’s services are Jews, looking to locate their relatives’ burial sites,” Silvia says. “It was a bit of a crazy idea, but I felt it was the only way I was going to unravel the mystery of my grandfather’s role and get closure. We formed quite an unlikely alliance, although he told me I was the second one who had come to him wanting to investigate a relative’s anti-Jewish atrocities.”

Dovidavicius helped her uncover information indicating that Jonas Norieka conducted the initial aktions even before the Germans arrived, with the enthusiastic help of the Lithuanian locals, many of whom viewed Jews as the agents of the Communist Soviet enemy.

“My grandfather taught them how to exterminate the Jews efficiently: how to sequester them, march them into the woods, force them to dig their own graves and shove them into the pits after shooting them.

“In Plunge, he gave orders to kill all the Jews, over 2,000. That was ahead of the Nazi takeover. Then in Siauliai, where he became chairman of the district from August 1941 to March 1943, he wrote hundreds of orders, but only three of them were translated into German for the Nazis — which means that those orders were directly for the Lithuanians.”

Silvia spoke with many survivors of the period, including her mother’s first cousin, who remembered babysitting her mother in Plunge in 1941 soon after the family had moved into a new home. She told Silvia how Jonas Norieka moved his family into a house in the center of town once it became “suddenly free” after the Jews disappeared. The house faced police headquarters-turned Nazi command center on one side, and stood next to the town’s synagogue on the other, where the Jews were crammed in before being marched into the woods and shot.

By the time she’d finished digging up the past, Silvia realized that her grandfather had sanctioned the murders of 2,200 Jews in Plunge, 5,500 Jews in Siauliai, and 7,000 Jews in Telsiai, and commissioned the plundering of their property.

Jonas and Antanina Norieka as newlyweds. When Silvia began her research, she hoped against hope that she’d be able to exonerate her grandfather, clear his name for good

Wrenching Admission

During that visit, Silvia spoke with the director of the state-funded Genocide and Resistance Research Center, which she later discovered had been ignoring calls for years by Jewish groups to review Jonas Norieka’s status as a national hero because of his Nazi collaboration in the murder of Lithuanian’s Jews.

“I asked the director about the primary-source documents I had, indicating that he’d sent thousands of Jews from various villages to their deaths,” Silvia relates. “Why was he still considered a hero? The director told me, ‘Yes, it’s true, but it’s hard to know what he really felt in his heart when he signed those orders. So we have to presume him innocent.’ I was astounded. This was my first exposure to how Holocaust distortion works in Lithuania. And why not? My grandfather looked like a movie star. He was a very handsome, charismatic man. How could he be a villain?”

Still, there was a big mystery Silvia needed to solve before heading home: If her grandfather was indeed a willing collaborator, and not simply following the distasteful orders of an occupying power, why was he interned in a concentration camp from 1943 until the end of the war in 1945 with other political prisoners?

She unearthed memoirs of other camp survivors and archived documents, and soon was able to paint a clear picture of what transpired. She discovered that SS commander Heimlich Himmler had personally given Norieka, along with 45 other Lithuanian officials, honorary prisoner status.

“I’d actually heard about that before —that’s how my grandfather was able to remain healthy and write letters to my grandmother, but I never gave it much thought. My mom and grandma always presented it like, ‘Oh, your grandfather was so special, he was even made an honorary prisoner in a Nazi concentration camp…’ But then digging into the story and looking at it a lot more critically, I started asking myself, why really did he and his fellow officers get such better treatment?

“The Lithuanian researchers told me they gave him that status because they didn’t want to get a reputation for mistreating the Lithuanians. But the Jewish scholars I spoke with painted a different picture: It was a reward for helping cleanse the country of the Jews. There were several high-profile perpetrators, and one of them was Jonas Norieka.”

The incarceration of the Lithuanian officers happened after the battle of Stalingrad in 1943. The Nazis had taken heavy losses, and at that point, they decided to boost their ranks by offering the Lithuanians the “privilege” of joining the SS. But, says Foti, that’s when the Lithuanians finally rebelled. They boycotted all the SS draft stations, and instead sent old men with canes wobbling into the centers. This enraged the Nazis, and in retaliation, they took 46 Lithuanian leaders to the Stutthof concentration camp.

For the first six weeks, they were beaten, starved, and forced into hard labor. But after six weeks, Himmler designated them as honorary prisoners, which meant they had their own barracks with beds, sheets, pillows, quilts, a radio, newspapers, and good food, and could write letters home and receive packages and money. For 92 weeks, this was their status.

In 1944, Antanina Norieka and her little daughter Dalia Maria, Foti’s mother and grandmother, fled Lithuania and traveled to Argentina, where they planned on waiting out the war and eventually being reunited with Jonas. (They wound up staying for over a decade until they could arrange visas to the US.) A year later, World War II was over, the Soviets arrived in Lithuania, and the Nazi prisoners were evacuated. There was a window when they could have left the country and many of them did. Norieka, too, could have rejoined his family, but, patriot that he was, decided instead to stay put and spearhead a resistance movement against the Soviets — that’s when he took on the name General Storm.

In November of 1945, he led a failed rebellion against the Russians, was captured by the NKVD, and was tortured and executed on February 26, 1947. He was shot in the head, and his body was tossed into a muddy pit with hundreds of others, his remains never identified.

“My grandmother didn’t know anything about his death,” Silvia says. “They only found out about it in 1956, the year they came to the US. They always assumed he was alive and that they would be reunited.”

In the 1990s, the Lithuanian government was considering creating a mass gravesite where NKVD and KGB prisoners were buried.

“There were about 800 bodies there, and my brother and I hoped we’d be able to identify our grandfather’s remains through DNA testing, but they’d put limestone over the bodies and that made them deteriorate to the point where they were unidentifiable,” Silvia relates. “We tried again a few years later, as the technology had gotten better. But it still didn’t work. Although we wanted to bury him, we were never able to make an identification. It took me many years to realize and accept the poetic justice of it all. How many thousands of Jews have no burial site or identification?”

Silvia can’t help mentioning the irony of her grandfather’s death, the way he was killed and his body discarded in much the same way as the Jews were killed under his orders. Still, it’s a wrenching admission, especially when it’s your own grandfather whom you’d worshipped your entire life.

“It was a long, emotional process for me,” Silvia admits. “It’s a horrible truth, very painful and very traumatic, but the only way to move on was to face it.”

The house in Plunge that Jonas Norieka and his family moved into after he rounded up the Jews and had them killed. On the left is the town’s shul

Tears from Heaven

After Silvia Foti’s return from Lithuania in 2013, it took her another five years to complete the book. During that time her family was dealing with another, more personal crisis — her daughter’s heroin addiction, to which she finally succumbed in 2015. The family collapsed in grief, the loss so acute, she says, that — although a devout practicing Catholic — she began to question the meaning of every aspect of her life. But then she rallied, with a renewed sense of clarity, about using one’s time in this world to do the right thing. “At that point,” she says, “the worst had already happened to me.”

In 2018, when she’d finally completed the manuscript, she created a website about her research and her journey, and began to look for a literary agent. She also published an article about her research in the on-line magazine Salon, to give the manuscript a preview boost. Within just three days, she received an email from a researcher in Lithuania who was working for a Jewish man of Lithuanian descent named Grant Gochin, an activist for Holocaust truth who was launching a lawsuit against the Genocide Research Center for Holocaust fraud and distortion. South African-born Gochin, a financial planner and wealth advisor living in California who serves as honorary consul for the Republic of Togo and is past special envoy for Diaspora Affairs to the African Union, lost dozens of family members in the Holocaust. Today, he wants all state-funded institutions to cease honoring Nazi collaborators such as Jonas Norieka.

Gochin’s researcher suggested they meet.

“I was freaked out, upset and scared,” Silvia says. “I was shocked because until then it was just a family story, but now there’s even a lawsuit on this regarding my grandfather and genocide? How much bigger was this going to get? How many others were aware of this? It was painful and overwhelming, and I initially didn’t want to call him, especially since my grandfather played a role in killing his relatives. Many of Gochin’s family members had lived in Papilė, a small town under my grandfather’s jurisdiction, where they were rounded up and murdered in October 1941. He probably wouldn’t even want to talk to me.

“After about six weeks, I finally worked up the courage. I said to myself, ‘Who am I writing this book for, if not for people like Grant Gochin?’ ”

Foti and Gochin eventually teamed up: She filed affidavits of support for his (ultimately unsuccessful) lawsuits in Vilnius and the European Court of Human Rights, and for an upcoming suit before the UN. But she’s gotten a much cooler reception from some of her own family members.

“My father, for example, became very uncomfortable about the whole thing and tried to talk me out of pursuing it. He kept telling me, ‘Why does it have to be you? Why can’t someone else do this? Find some historian with a PhD and let them do it. Why do you, the granddaughter, have to get involved?’

“But eventually I realized that because I’m the granddaughter, I could get more attention on this than anyone else.”

Silvia doesn’t deny that although the book has become an important document in the realm of Lithuanian Holocaust distortion, there is still some sense of shame and betrayal, a sense of loss and pride in who you think you are.

“But I have come to an acceptance, and in some ways the book has been a catharsis for me, and talking about it is a catharsis,” she says. “And really, the greatest strength I had to rely on getting through all this is my faith in G-d. My strength came through my prayers. I always had a constant prayer on my lips, something to the effect of ‘G-d, if this is true about my grandfather, You are going to have to help me get the story out. I’ll show up as the writer and do what I have to do from my end. And if it’s not true, just block it. And, help me get through this myself, because this is not easy.’ ”

Maybe Silvia’s own grandmother hinted at the answer when she once told her, “When it rains, it means G-d is crying over somebody. If a country calls itself the Land of Rain [what Lithuanians call their country], it means G-d is crying over everybody.”

Perhaps Silvia herself best summed up the roller-coaster ride she’s been through while visiting the town of Zagare in Lithuania, where more than 2,000 Jews were killed. After standing near what was once a massive pit, drenched from the unrelenting rain, she penned the following: “This is where my grandfather sent the Jews, 2,236 bodies lie buried in this unmarked grave. I’ve come to pray, but don’t know what to say. Is it enough to bear witness? I cannot undo the past or redress my grandfather’s actions but I am willing to face what was done. I am so, so sorry for the unimaginable loss.”

HEROES OR VILLAINS?

When Silvia Foti’s book was released in its first printing last year, it ignited a firestorm in Lithuania, fueling the public debate over Jonas Norieka’s legacy in particular, and what role Lithuanians in general played alongside the Nazi occupiers during the Holocaust, when an estimated 95 percent of Lithuania’s Jews were murdered.

The dominant narrative in Lithuania has long been one of national identity and pride in the resistance to both the Soviets and the Nazis occupations, a narrative that government officials have worked hard to reinforce. Streets and a school are named after Jonas Norieka, and there is a memorial plaque in his honor on the building where he worked and from where he led the resistance.

The state-run Genocide and Resistance Research Center of Lithuania, the official guardian of the country’s collective memory, has been one of Norieka’s primary defenders. In 2015, it issued a report that found that Norieka had no involvement in the mass murder of Jews. And in 2019, citing “reliable data,” the center said Norieka was even responsible for saving Jews through a rescue network.

But Grant Gochin, who aligned with Silvia Foti after her manuscript began to circulate, sued the Genocide and Resistance Research Center, claiming that his grandfather’s entire family were among the Jews who were killed by Norieka’s orders during his governorship of Siauliai County. The court in Vilnius, however, ruled that there was no evidence to suggest that Noreika was involved in the killing of Jews.

Yet the message was out. The plaque in Vilnius commemorating Norieka was smashed with a hammer. It was repaired, then taken down again weeks later at the urging of the foreign minister who was sympathetic to claims that the state had whitewashed the darker side of Norieka’s activities, and then installed again by a nationalist group who didn’t want anyone tampering with their heroes.

Gochin, for his part, remains undaunted. “It’s not only Jonas Norieka. I have provided the Lithuanian government with more than a dozen names of their heroes who were Holocaust perpetrators, and I’ve brought close to 30 legal actions against the government of Lithuania. Every case has been dismissed on legal technicalities,” he tells Mishpacha.

Gochin says that the Lithuanian Holocaust deception has become personal. “More than a decade after Jonas Norieka was exposed as the murderer of my own family, Lithuania declared him a national hero. But the truth is that he was a minor murderer in the greater scheme of things. He was only responsible for the murder of 14,500 Jews, but there were others, camp guards and commanders who were in charge of mass murder, who happily ran the gas chambers. Still, Lithuania was going to Jewish organizations and presenting itself as a rescuer nation, and the constant lies and intimidation tactics made me determined to show how much they had rewritten history, and how easily they had done it.

“While my case is currently in front of the United Nations and could take decades to be resolved, I believe the best immediate recourse is the court of public opinion. And that,” he says, “is us.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 922)

Oops! We could not locate your form.