The Last Link

| March 25, 2025Gestapo. Shards of glass. Escape. Tante Anne gave me my children’s heritage

“HI,Tante Anne!” I shouted into the phone. “It’s Lori!”

“Who is this, Lauren?” my great-aunt asked in her thick German accent.

“No, it’s me, Lori!” I yelled louder.

“Oh, Lori! Lori! I’m so glad you called. How are you?”

“I’m good, Thank G-d! How are you feeling, Tante Anne?”

“Oh, you know.” Tante Anne laughed. “At my age, nothing works so good anymore. How are you? How are the kids doing?”

“They’re doing good. Keeping me busy.”

“I was hoping you would call. I was thinking about what you told me last time — how you’re having trouble training your son. You should really ask your pediatrician what to do. They should be able to tell you — they see kids all the time.”

“That’s a great idea, Tante Anne!” I shouted. “I’m going to do that!”

At 100 years old, my great-aunt still managed to live independently, in the same house where she’d raised her children. She was partially deaf, but her memory was sharp as a tack. Tante Anne would remember the details of every problem I had mentioned in previous phone calls, and she’d give me advice based on a hundred years of wisdom. Always upbeat and positive, she never wanted to speak about her own health problems, but instead about the little problems of my young family. “Thank you for calling,” she would tell me before we hung up. “Most people aren’t interested in old people. It’s so nice that you call.”

I was always close to my great-aunt. She lived near us and always came to our Passover Seders. I’d also see her and her adult children, Lynn and Eddie, at the family get-togethers we managed to make once or twice a year. But it was only after all my other grandparents and their siblings passed away that I started to call and visit her more often. She remembered a whole world that’s slowly fading from memory, and she made me feel connected to the grandparents I had lost. I also loved her in her own right for the way she was grateful for any small kindness, and how she was always so happy to hear from me.

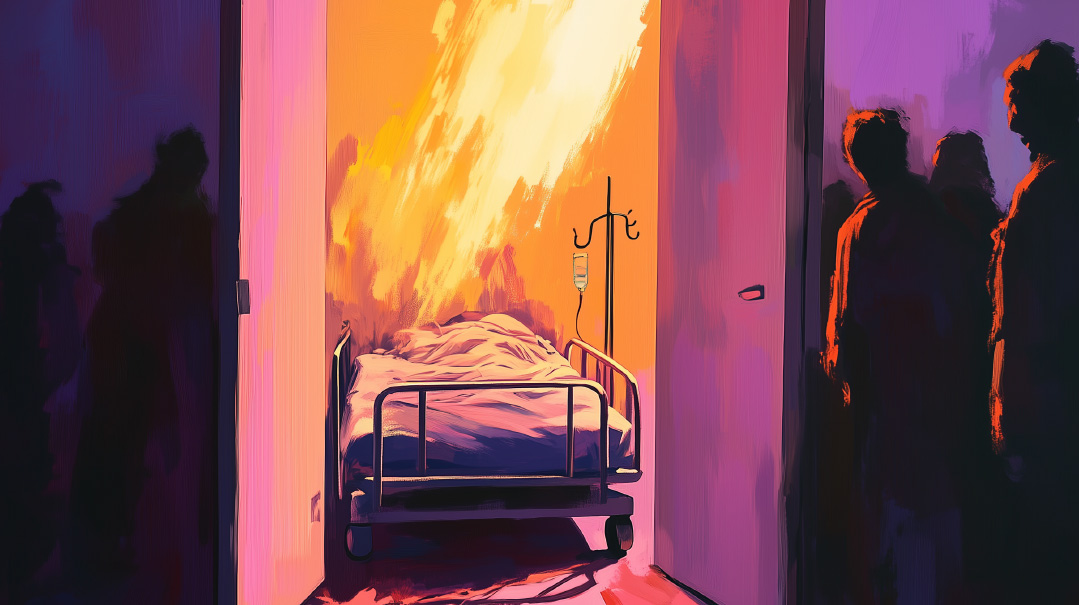

My Tante Anne passed away this past January. You’d think that since she lived to be a hundred, her death would not be such a blow to her family. We had many long years with her, and she got to see great-great-nieces and -nephews. But it still feels incredibly sad. She was the last of her generation; we’ve lost a link to the past.

But memory is a strange thing — it allows us to live on in this world even when we’re no longer present. For so long, my Tante Anne was the repository of all our family stories spanning back a hundred years. Now that she’s gone, we’re passing on those memories to the next generation.

A

bout a year before she passed away, I interviewed my great-aunt about her experiences during Kristallnacht. In her lifetime, Tante Anne asked me not to publish it. She was afraid that if she spoke publicly about her experiences, anti-Semites would find and harass her. (After everything she had gone through, and the amount of anti-Semitism we’re witnessing today, I know her fears were all too rational.)

Tante Anne was 99 when I visited her in her home in Queens, New York for the interview. Her home was remarkably clean, especially considering that she wouldn’t allow a housekeeper inside her house. My great-aunt was neat as a pin all her life and took great pride in maintaining her home. If you left a book with a bookmark on her coffee table for five minutes, you’d come back to find the book on the shelf and the bookmark put back in the drawer where it belonged.

Even though Tante Anne hadn’t redecorated since the 70s, everything from the orange carpet to the shaggy couch was pristine, as if it was being preserved for a museum.

Now, I sat on the couch across from Tante Anne.

“So what does the journalist want to know?” she asked with a laugh, as she took in my pen and pad.

I laughed, too. This felt very different from my usual visits. I always loved to talk to Tante Anne about anything and everything, but today I was here with a purpose. I’d heard some of my family’s story in snippets told by my mother and my Oma a”h, but today I had come to record the whole thing start to finish. I wanted to preserve this history for my children and, one day, for my grandchildren. This was their heritage.

“Let’s start at the beginning. When and where were you born?”

“I was born in Passau, Germany, in 1924. Passau is a small city with three rivers that flow through it. It was a beautiful place to grow up.” Tante Anne sighed at the memory. “Before the Nazis came to power, I had a wonderful childhood. I loved swimming, ice skating, picking strawberries, playing with marbles with my friends. We used to take vacations to the Alps in the summer.”

“What was Jewish life like there?”

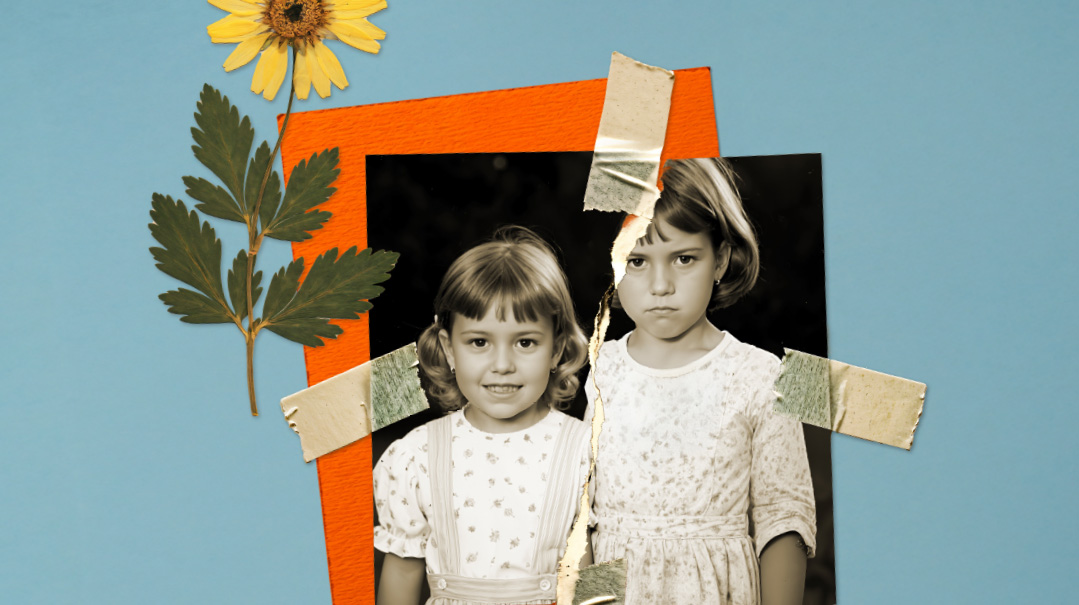

“There were only ten Jewish families in Passau, and my father would lead the services on the High Holidays. My parents hired a rabbi to come in from another city and prepare my brother for his bar mitzvah.” Tante Anne was the youngest of three children. The oldest was my Oma, and they had one brother, Gunther.

“Were you religious?” I asked. As a baalas teshuvah, I knew that my family wasn’t strictly Orthodox in America, but I wasn’t sure what their observance had looked like back in Germany.

“We were proudly Jewish, but we considered ourselves as German as we were Jewish. We felt proud to be German.”

I looked at her askance. “Why would you be proud to be German?”

“Because of their culture, their music, their philosophy. We thought we were part of the best country in the world. But in the end, of course, it didn’t matter. My grandmother had lost two sons — two out of her five children — fighting to defend Germany in World War I. But it made no difference to the Nazis. No matter how German you thought you were, to them you were a Jew.”

“What do you remember about when the Nazis came to power?”

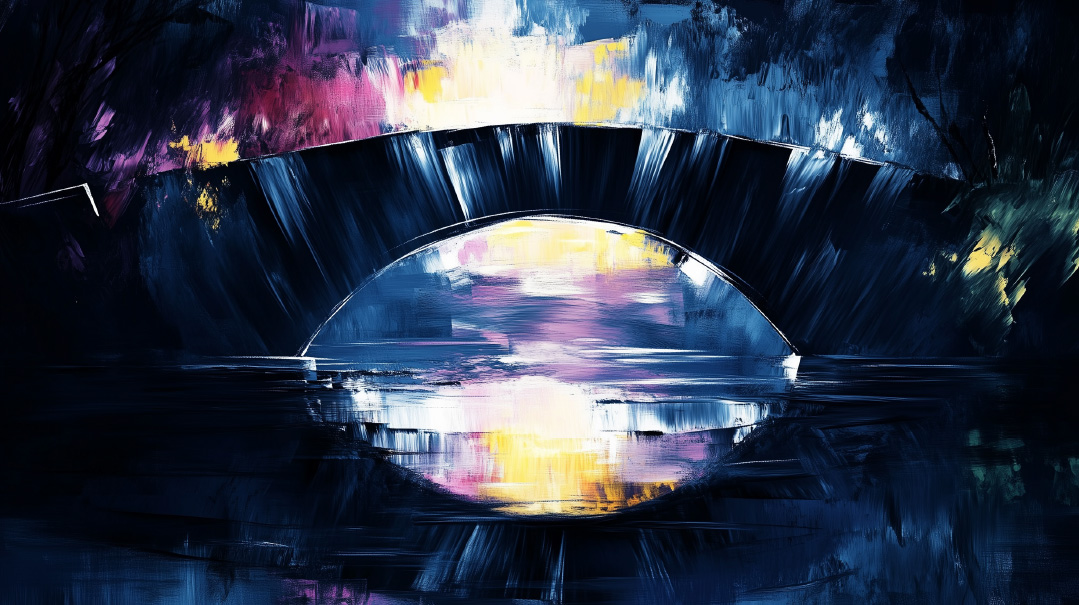

“I remember one day my mother was taking me and my siblings for a walk — I must have been around eleven and your Oma around fifteen. We were crossing a bridge when we suddenly saw the Nazi youths in their uniforms marching toward us, singing a song in German that goes something like, ‘How wonderful it will be when the walls are covered with Jewish blood.’ In a small town like Passau, everyone knew we were Jewish, and they were marching right toward us. What could we do? If we started running, they would chase us. If we tried to go past them, they could hurt us. My mother said, ‘Kinderlach, let’s look and see if we can find a four-leaf clover,’ and she had us move to the side of the bridge and bend down in the grass, out of the way of the Nazis. Thank G-d, they passed us by.”

Just hearing the story and imagining the Nazis marching in rows toward my relatives has my heart in my throat. I can’t imagine how my great-grandmother must have felt. “You must have been so scared,” I said.

“At the time, I didn’t fully understand what was going on. It’s only looking back that I realize what a bad situation we were in, and how clever my mother was.”

“What did the Nazis do next?”

“Hitler called for a boycott of Jewish stores, which destroyed our family wine business. I wasn’t allowed to go to school and just stayed home. For me the most painful part was that my best friend wasn’t allowed to play with me anymore. I begged and pleaded with her. I asked her, ‘What did I do wrong? Why won’t you play with me?’ but she never spoke to me again. Her parents must have told her not to.

“Before Hitler, we had good relations with our non-Jewish neighbors. We were very surprised at how they turned on us. We were taking a walk with our non-Jewish nanny, and a neighbor stopped the nanny and said, ‘Don’t you have anything better to do than to watch Jewish children?’ The landlord wouldn’t rent to us anymore, so we had to move from Passau to Munich.”

I had known that Hitler destroyed the family business, but I never knew that the landlord had evicted them, or that my Tante Anne’s best friend had rejected her so cruelly. Of course, it’s a trivial thing in the grand scale of the Holocaust, but it’s still such a painful memory that my Tante Anne had carried it with her her entire life.

“What happened to your family on Kristallnacht?” I asked. Kristallnacht was the day that had changed everything for German Jews. It was the beginning of the end of thousands of years of Jewish life in Germany, and I had never heard the whole story of what happened to my family on this dark day.

“I was home with my parents and brother — I was fourteen years old at the time. A family friend had warned my parents that the Nazis were planning to do something big against the Jews, but no one knew what it would be. At six in the morning, on November tenth, there were loud knocks on the door. I was the one who opened it up, and there were two Gestapo officers standing there.”

I put down my pen. “I didn’t know you were the one who opened the door for them! You must have been terrified.”

Tante Anne nodded. “They said they were there to take all the men. They took my father, and then they were talking to each other about whether to take my brother, Gunther. He was only fifteen, and they weren’t sure if they were supposed to take children or not, and if he should be considered a child or a man. My mother tried to convince them that he was younger than he was, and in the end, they only took my father. I remember he was not allowed to pack a bag to take with him, but he wore warm undergarments under his clothes.

“We had no idea where they were taking him, and of course my mother cried and cried. I was so scared — I had no idea if I was ever going to see my father again. We stayed inside that whole day, and then, when we went outside the next day, we saw all the Jewish stores had their windows smashed in with shards of glass everywhere. The stores had all been looted, with nothing left on the shelves.”

“Where was Oma during this?” I asked. Foolishly, I had never thought to ask my grandmother about her memories of Kristallnacht. I had a close relationship with her, but we talked about day-to-day things — school, friends, music. Even when we had spoken about her childhood in Germany, she had never spoken about Kristallnacht; perhaps it had been too hard for her.

“She was in Berlin with our aunt and uncle. They ran a bookstore and every year on our birthdays they would send us a book. That was a big treat for us back then! When the Jews were kicked out of school, our parents thought that Inge should keep busy. She was the oldest and had nothing to do, so they sent her to our aunt in Berlin. They had two young boys, and they needed someone to help watch them while they ran the bookstore.”

“What did she see during Kristallnacht?”

“The Gestapo burned down our aunt and uncle’s bookstore and arrested our uncle. Our aunt and grandmother were terrified. Your Oma had to leave them to go to the embassy in Stuttgart. She stood on a line down the street to try to get visas for us to leave. Emigrating was a lottery system, and we drew a low number, which meant we would be allowed to leave. We needed someone to vouch for us, and luckily, we had a nanny who used to work for us who had moved to America. She was willing to vouch for us.”

“And what about your aunt and uncle and cousins? Was Oma able to get visas for them to leave, too?”

My heart hung in my throat as I waited for Tante Anne’s reply. She didn’t answer right away. She got to her feet with the help of her walker and went to the kitchen and shuffled around, making herself a cup of tea — I could hear the kettle whistling on the stove, and smell of chamomile wafting through the air. It was a comforting hominess in stark contrast to the terrible events we were discussing.

While Tanta Anne was in the kitchen, I thought about what I’d learned about Kristallnacht. I knew that Jewish homes and businesses all over Germany were destroyed and ransacked on that terrible day. Jewish businesses and synagogues were destroyed and set on fire. Jews were attacked and beaten, and 30,000 Jewish men were rounded up and sent to concentration camps. But hearing how it had affected my family made it all too real.

After Kristallnacht, many countries, including the United States, imposed strict quotas on Jewish immigration. While tens of thousands emigrated, over 200,000 were left behind. Even the ones who were allowed to immigrate sometimes went to other European countries where they were subsequently murdered.

“What can I get you to eat?” Tante Anne asked, coming back into the living room with her cup of tea. “Are you hungry? I have cookies. Eddie got them for me — they’re glatt kosher.”

I took a cookie even though I wasn’t hungry. I sensed that Tante Anne needed a break from all these tough memories.

“Did you ever see your father again?” I asked after a few minutes.

Tante Anne put down her tea. “Six weeks later, I heard the doorbell ring. I opened the door and there was my father — unshaven and looking thin and sick. I can still remember how my mother screamed and cried when she saw him at the door. He had been in Dachau the whole time. I don’t know how he got out, but it was a huge miracle. He never spoke much about his time there.”

“And your aunt and uncle, your cousins, what happened to them?”

“They were all murdered.”

We sat in silence for a minute, the words in the air like a physical thing between us. The sun was setting outside the window, and the sky was turning purple. Tante Anne polished her glasses on the hem of her skirt, and when she spoke again her accent seemed thicker than it had a moment ago. “So, what else would you like to know?”

I picked up my pen. “What happened when you left?”

“The Nazis took everything, everything. They wouldn’t let us take more than five dollars with us. We went on a boat, and when we got to America we settled in Albany, where we had relatives who had come to America in a previous generation. The German-Jews in Albany were settled and we felt that they looked down on us new immigrants, with our accents and our poverty. Still, they helped my father find work in a factory and helped us find an apartment. It was tiny, and we didn’t have money for mattresses. In the beginning, we slept on blankets on the floor. My brother worked for a jeweler. My sister worked as a baby nurse.

“I was able to finish my last year of high school, and then I went to work in a department store. It was hard getting used to life in America. There had been so much beautiful nature in Passau, and in Albany there were a lot of factories. It was a dirty city at the time. But we heard the stories of what was going on in Germany and what was happening to our friends and family, and we knew we were lucky to be alive.”

I scribbled it all down. This was no German-Jewish immigrant story in textbooks; this was my family.

“How did you meet your husband?” I asked. I have only the vaguest memories of my Great-Uncle Ernst. I remember a delicious chicken and star-shaped pasta soup he made for us when I was a child and that’s about it. My mother always told me he was a great cook and a jovial person whom everyone liked. Now I wanted to know everything.

“I met my husband, Ernst, through a German-Jewish pen pal program between Jewish soldiers and Jewish women in America. He was serving in the army in the Pacific during World War II, and I wrote him letters. When he got back, we met, and he asked me to marry him. We moved to Jamaica, Queens, which at that time had a vibrant Jewish community. We joined the shul there, and together we built a business making cake decoration toppers. I did the bookkeeping, keeping track of the orders and the payments. I worked in the business well into my nineties.”

“Into your nineties?” I echoed incredulously. I had no idea she was still working. I had just assumed she had retired decades ago.

Tante Anne laughed. “Even now, I try to help out with one or two things that I can still do.”

“Wow,” I marveled, “there aren’t not many people your age working. How do you think you’ve managed to live so long?”

“Well, I never smoke or drink, and I eat a lot of fruits and vegetables.”

“What was it like raising your family as an immigrant? Did the Holocaust overshadow everything? Were you nervous for your children?”

“I wouldn’t say that I was nervous, but we had to work very hard to put food on the table. It wasn’t easy. We did enjoy going to the Catskills as a family in the summer. Those were very nice times for us.

“Ernst died in 1993, so I’ve been widowed for many years, but my friends call me the merry widow because I’m always happy and grateful for all the good in my life — for my friends and family.”

Tante Anne yawned, and I looked at the clock on the counter. I couldn’t believe I had already been there for two hours. It felt like the time had just flown by. “You’re incredible, Tante Anne,” I said, getting up from the couch. “There’s no one like you. It’s amazing how much you remember. No one has a memory like yours at a hundred.”

“Well, I think I’ve told you everything I know,” Tante Anne said with a laugh. She stood up, too, supporting herself with her walker.

“Don’t stand up for me!” I told her. “I can let myself out.”

But Tante Anne was already up and walking me to the door.

WE held a big party for Tante Anne at her house for her 100th birthday. Relatives flew in from all over the country, and I brought my children over to Tante Anne so she could shep nachas.

We ate cake and chatted, and Tante Anne took it all in, not able to hear much, but smiling at us from her cozy armchair and commenting on how cute her great-nieces and great-nephews are.

“We’ll have another party for you when you reach a hundred and one,” I told her, leaning in for a kiss.

She laughed. “I’m not going to make it that long.”

“Don’t say that. You will,” I promised.

But in the end, she was right. That would be her last birthday party.

When I told my eight-year-old daughter that Tante-Anne was niftar, she was heartbroken.

“I’m going to miss her,” she sniffed. “Why did she have to die?”

“I know,” I said, bending down to give my daughter a hug, “we’re all going to miss her, but not many people get to meet their hundred-year-old great-aunt. You were lucky you got to know her so well, and you’ll always remember her.”

My daughter nodded. “I will.”

“When you get older, I’ll tell you some of her stories. Your Tante Anne lived through a lot.”

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 937)

Oops! We could not locate your form.