The Dust Bowl

| October 12, 2021When dirt fell from the sky

1935

The big cloud overhead looked threatening. Frances tugged at her father’s sleeve. “Papa, Papa, look at that!” she said, pointing.

Her father put down his hoe and gazed up at the sky, worried. “That’s not rain! Oh no! Another dust storm is coming!”

Quickly, the family sprang into action. They hurriedly brought all the animals inside the house. They stuffed sheets into the cracks in the walls. They covered the well with a big stone. Then, they huddled inside the house, damp rags covering their mouths and noses, as the dust storm rolled into town, covering the streets with darkness.

An Appropriate Nickname

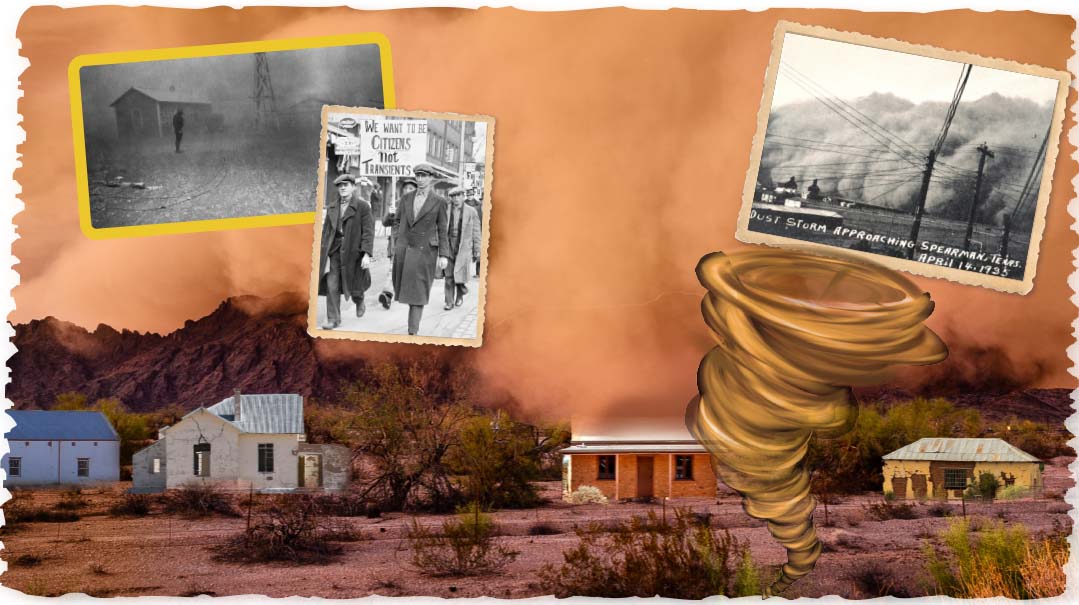

On April 14, 1935, Colorado, Kansas, and the panhandle of Oklahoma, otherwise known as the Great Plains, were given an interesting nickname.

It was after a massive storm where the winds blew harder than 60 miles per hour. Reporters all wrote about it, and one came up with the nickname that stuck immediately: The Dust Bowl.

Most of us are familiar with dust, the substance that we find on top of bookshelves or in old attics. But for the residents of the Dust Bowl… dust was their daily routine.

For close to ten years, instead of rain falling from the sky to water their plants and grow their crops, dust swept through the towns, destroying the crops and getting into all their belongings.

But where did all this dust come from?

And why didn’t it rain?

That area, the Central Southern region of the United States, was famous for its crops. Most of the wheat that the United States produced came from there. For years, the farmers toiled hard on their farms — and they got results. Although there were occasional droughts and plagues of grasshoppers, for the most part, they made enough money to feed their families. Some even became wealthy from their efforts and developed big plantations.

So what changed?

1914

In 1914, World War I broke out. Suddenly it wasn’t just Americans who wanted the wheat that Kansas and Oklahoma grew. Everyone, it seemed, wanted their crops. The world was at war! The US government needed wheat. Other countries needed wheat. The farmers grew their wheat and watched the money flow in.

But the wheat that they grew just wasn’t enough.

Overworking the Land

1917

The Smith family had been working in the field for hours.

“Come on!” their father urged them. “We’re going to plant another field.”

Jimmy looked up from where he was plowing the soil. “Where can we plant another field? I thought that we used up all the fields that are good for planting wheat.”

“Oh, don’t worry,” their father reassured them, “we’re going to use the field behind the house.”

“But Papa,” Frances asked, “didn’t you always tell us that field wasn’t good for planting wheat?” Their father rubbed his hands together. “Oh, don’t worry about that, children. Do you know how much money we can sell a bushel of wheat for?” He laughed. “We’re going to be rich! The field will be fine.”

While they were plowing the new field, Mama came out of the house looking concerned.

“Why did you stop the soil conservation practices?” she asked Papa.

Papa waved his hand, dismissively. “It will be fine. Nothing will happen.”

What are soil conservation practices? In order for the soil to stay healthy and keep producing good crops, farmers utilize certain practices to conserve the soil. Some of the things they do include fertilizing the land and allowing the fields to rest every few years by not planting anything. In the early 1900s, farmers didn’t know just how dangerous it could be to stop these practices, which diminished the amount of wheat they could grow. With so much money to be made, they decided it wouldn’t hurt to stop following these practices and simply grow as much wheat as possible.

Farmers all over were ignoring the rules of taking care of the soil in response to pressure from the government and the lure of money. The soil was overworked, and the sod, the top part of the soil that protects the soil, eventually started wearing away.

For four years, farmers produced enormous amounts of wheat. Their bank accounts grew larger. The rain fell regularly, and life was good.

And then… the war was over. The demand died down. Other countries started producing their own wheat again. The army had less need for wheat. Suddenly, it wasn’t so easy to sell their wheat.

Prices dropped. A lot.

Now the farmers had to produce even more to make the same amount they had made before the war. They worked the soil even harder.

They struggled. There were droughts. The soil did not produce the same quality of wheat that it had in the past. But most farmers managed all right, until 1929.

1929

Papa came into the house, his face white. He held up a newspaper. The headline read: “Stock market crashed. Investors lost everything.”

“We have nothing left,” he told Mama hoarsely. “The bank closed down. All the money is gone.”

“At least we have our crops,” Mama said comfortingly.

“If anyone will buy them….” Papa muttered. “And I owe people money for the new tractor I bought. I have to pay the mortgage on the farm. What will we do?”

The Smiths weren’t the only ones suffering. Many people lost all their money and their means to earn money. People were thrown out of their homes. They were starving in the streets. The government was in crisis mode, trying to fix everything.

The farmers couldn’t sell their wheat. No one could afford to buy it.

In the past, during a hard year, the banks were forgiving. They would extend the mortgages. Farmers could buy items on credit. But not this time.

It was the Great Depression, and the entire country was out of money.

The Droughts

If all that misery wasn’t enough, in the early 1930s the droughts started.

The Great Plains (this Southwestern region of the US) were used to droughts, which occurred every couple of years. During that time, you just prayed for rain and hoped for the best. You ate a little less, made a little less money, but you survived.

This was much worse. This time, people living in those states were starving, just like the rest of the country. During past droughts, they had begged and borrowed money from their wealthy relatives. Now, their relatives were just as poor as they were.

The worst problem was the soil. After the war, to make more money, famers had squeezed more cattle and sheep onto smaller areas of soil. They also stopped the conservation practices and kept plowing up the sod, which damaged the soil and made it very dry. Water rests underneath the sod, but if there is no sod, then the water dries up. When the strong winds blew, which was often, the soil turned to dust and blew away. Because the soil had been ruined during the war years, with every gust of wind, it rose up into the air and created dust storms.

It was a vicious cycle. Because there was no rain, there were dust storms, which dried up the soil and created more dust.

What was it like to live in the Dust Bowl?

We’re used to dust as a thin substance that doesn’t really hurt anyone. The worst it might do is make you cough when you climb into an old attic.

This was different. So much dust would coat the ground after a dust storm that it would be as heavy as a layer of snow — if not heavier. And the health effects were a lot more damaging. Children during that time had no idea what rain was. They had never seen it. All they knew was dust. Thick black dust that got into their noses and clothing and made them sick.

When it did rain, people would literally dance for joy. They would leave every pitcher and cup they had outside to catch the precious drops. Unfortunately, the rain often came down too strongly for the delicate soil. Sometimes the farmers would stand there and watch as the seeds they had planted only minutes before flew out of the ground from the strong wind.

Houses in those days were not built that well, and dust would fly in through every crack between the wooden planks. Women would cover all their food when they set it out on the table. Even if it was only five minutes before the meal, the food would get full of dust if left uncovered. No matter how hard they tried, the residents of the Dust Bowl just couldn’t keep the dust out.

Instead of blizzards of snow, there would be blizzards of dust. Once, a train coming in from Santa Fe got blocked for days because mountains of dust prevented it from continuing forward.

Buried under Dust

1935

The Smith family had beaten the dust storm into the house and were frantically putting sheets in the cracks in the wall when there was a banging on the door.

Mama quickly opened it. A family of four stood at the door. Their faces were already caked with dust. Mama hurried them into the house.

“Thank you so much!” the father gasped. “We were on the way back from visiting my sister when this dust storm blew in, and your house was the closest.”

It didn’t matter that the Smith family had never seen this family before. During a dust storm, you gave shelter to whoever needed it.

“We’re happy to do it,” Mama said softly. “All of us have needed shelter at some point.”

When the dust storm blew itself out, the cleanup process began. It could take hours, or even days, to get everything cleaned up.

“Look!’’ Jimmy said, pointing at the coop. “The chickens all went to sleep again. Right in the middle of the day!” It was so dark during dust storms that the chickens believed it was nighttime and fell asleep.

There was also a danger of fire during this time. Because the states were so dry, fires started easily. And once they started, there wasn’t enough water to put them out. When fires broke out, all the firemen could do was move anything that was flammable away from the fire. There was little hope of putting out the fire; all they could do was make sure that the fire wouldn’t spread.

How were they helped? How did the farmers manage to rebuild their lives and repair the soil? Many of them couldn’t wait and moved out of the Great Plains. But for those who hung on, the government stepped in.

Rebuilding

“How will we grow new crops, Papa?” Frances asked her father as the dust howled around their house, destroying their crops for the fourth time that summer.

Papa looked tired. “The government is lending us money to pay for it.”

“But when will we have to pay it back? What if there isn’t enough rain?” Jimmy said, worried.

Papa smiled tiredly. “They said we don’t have to pay until the new crops come in.”

“And if they never come in?” Mama said softly.

Papa sighed. “Then we won’t have to pay a cent.”

Congress also passed the Soil Conservation Act, where they paid farmers to conserve the soil. Congress did not initially want to pass the act, but then a dust storm arrived in Washington, having been carried all the way from the Central Southern States. That convinced Congress.

The government would pay farmers 50 dollars (which was a lot of money at the time) to plant certain crops or not to plant at all. They encouraged the farmers to plant more trees, hoping it would cause rain, and taught the farmers the best way to plant so the soil wouldn’t dry up.

It didn’t happen right away, but eventually life went back to normal. By the end of the 1930s, rain started to fall regularly again, and the dust storms stopped coming. Their wheat grew tall again, and crops were healthy.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Jr., Issue 881)

Oops! We could not locate your form.