The Bigger Picture

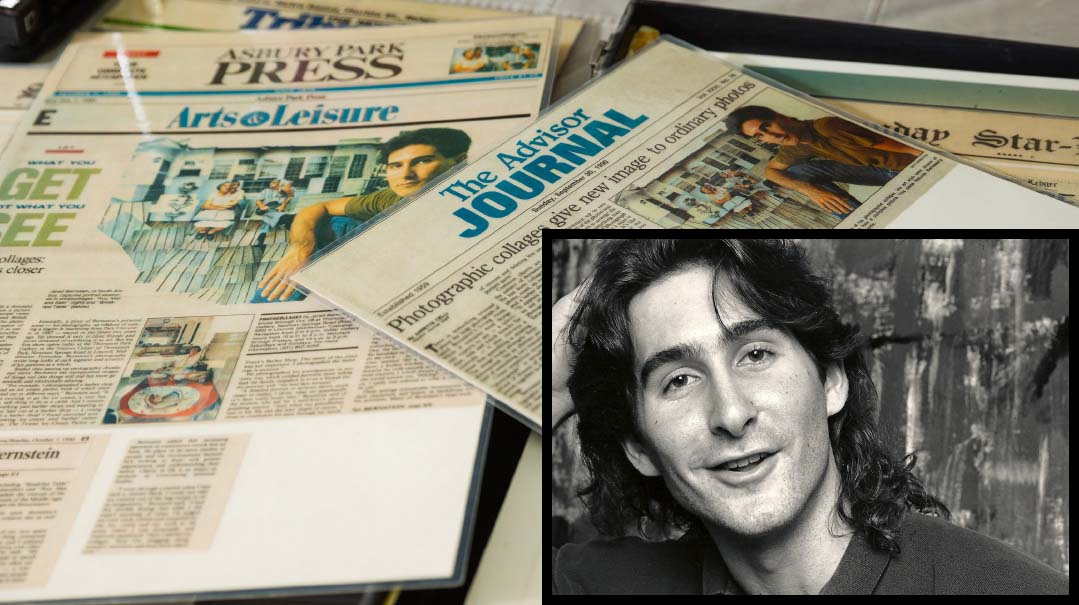

Former celebrity photographer Jared Bernstein walked away from it all when he realized the flash was missing

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Jared Bernstein Photography

Even if you’re one of those people who think modern art looks like someone accidentally kicked a bucket of paint over a canvas,

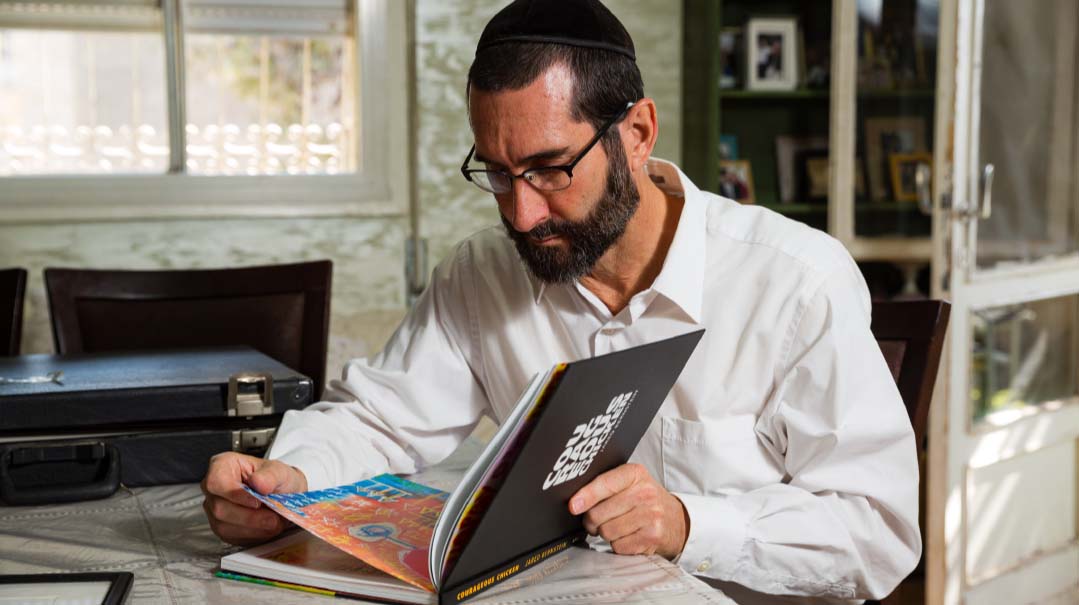

chances are you’ll still be touched by an unconventional new book called Courageous Chicken: A Journey to Living Courageously. It’s the very personal account of former celebrity photographer Jared Bernstein, portrayed through his paintings and poems: an exploration of his fears and triumphs as he exchanged the glitz and glitter of inner-circle access to top-tier musicians, actors, and real estate tycoons (including Donald Trump) for a life of Torah observance in Eretz Yisrael.

If you’ve been to upscale weddings in Israel in the last decade, you’ve probably seen Jared — the unruffled, confident photographer with the black yarmulke, white shirt, and neatly trimmed beard who’s always calm and focused under pressure, organizing those impossible family pictures, getting overtired kids to smile. Yet behind the wedding photographer’s camera lens is an artist’s soul.

“In the book, through my paintings and my poems, I share my experiences of finding G-d and gaining the courage to transform my life,” Jared says, emphasizing that it’s not just a collection of modern art, but what he calls, “a public mirror to my soul. I grew up barely knowing I was Jewish, but despite the money and status I had, I wasn’t happy. In 1998 I found Hashem, walked away from that life, got married, moved to Jerusalem and was blessed with a beautiful family. But it’s taken me 23 years to get up the nerve to share my story. The book is a confrontation with my identity. It’s the story of my life, of my teshuvah, of my coming clean.”

Each time I face my fears and walk through / I’m triumphant / I could have easily changed my course, given up, folded my hand / My choice / Embrace the scared, vulnerable and obedient “chicken” in me / Courageously transforming into a powerful, fearless warrior that doesn’t allow thoughts / Like rejection, abandonment or failure dissuade him / My weakness connects me to my greatest strength / Vulnerability

Jared Bernstein was born 58 years ago in Baltimore, Maryland and moved to Marlboro, New Jersey at age five, when his father, a psychologist, got a position in a psychiatric hospital there. Although his mother was raised in a Shabbos-observant home, the only thing Jared and his two siblings knew about their being Jewish was their giveaway last name.

“If someone asked me if I was Jewish, I’d say, ‘I guess so’ — I mean, I knew I was, but had no concept whatsoever what that meant,” he says. He never went to Sunday school, was never even bar mitzvahed, and didn’t have a kosher bris (it was on day two in the hospital).

His parents did give him a “choice,” however. “When I was about 11,” Jared remembers, “my parents gave me an option: to continue on the soccer team or go to Hebrew school. Well, that wasn’t much of a choice. I didn’t even know what Hebrew school was.”

He had one connection to tradition, though: his mother’s parents. His grandparents lived in Flatbush and would come visit on Friday afternoons, bringing big pots of food. “The food was delicious,” Jared remembers, “but no one ever told us what that was, what kosher was. We just thought they had their own food preferences. My mom left religion when she went to college, and my dad, who was totally unaffiliated, made a condition when they got married: that her parents don’t mention anything about religious Judaism to their children. So she went along with it. When they would come on Friday, they weren’t even allowed to say, ‘you know, kids, it’s going to be Shabbos.’ ”

Although he couldn’t define it, he says there was something different about his grandparents (“Grandpa always wore a hat, and Grandma always dressed with dignity”) that gave him some stability in a turbulent home life — there was a lot of family dysfunction all along, and when Jared was 12, his parents divorced.

It was hard growing up amid so much tension, and Jared, always a sensitive kid, took to writing stories and drawing as a salve to his broken spirit. He says that already at around age ten, he had a sense that there was “something out there, even though I had no concept of G-d.”

From the time he was a teenager, Jared knew he wanted to be a photographer, but he says he didn’t have much confidence and wasn’t a risk-taker, so the easier path was to go to Pace University in Manhattan and pick up a “normal” degree in business and marketing.

Business really wasn’t his thing, though (before enrolling in university he got a real estate license but hated the profession), and meanwhile, he’d begun assisting a few Manhattan photographers.

“I moved through the ranks pretty quickly thanks to those guys,” he says. “They gave me an opening, I built myself up, and by the time I was around 25, I became the top guy. I connected with some of the big agents and started photographing celebrities and going on their entourages. I became the circuit photographer for two world-class rock groups, and after the Grammy Awards one year, I was hired to photograph the after-party for MCA records. Everyone in that room was a famous person, and soon I was going on the circuit with some of the big names in the industry — which was quite an ego thrill since I always considered myself a nobody.”

At that point Jared found another niche: working with New York’s biggest real estate tycoons. “Donald Trump was part of that crowd, although he was actually one of the lower-level people there at the time. This was the late 1980s, and we’re talking about people like Larry Silverstein who owned the Twin Towers, or multimillionaire businesswoman and television personality Barbara Corcoran — the heavy hitters and power brokers running Manhattan’s real estate. I became part of their entourages, one of the regulars on their yachts that were docked on 23rd Street going around lower Manhattan. They’d have what are called broker parties, these really over-the-top parties either on their boats or in their apartments, which were a combination of ego-stroking, showing off, and also business. But it was always about wanting to be photographed and seen with the right people.”

What was it like being in the inner sanctum of the rich and famous? Jared says that after the initial “I can’t believe I’m in the room with them” feeling, there was a bit of a letdown.

“When we’re young, these are our idols, but then you’re on the yacht with them, and they’re just so busy jostling for position to feed their egos. I realized that most of them were not modeling how I wanted my own life to be. I was moving along with them — a lot of the job is the personal interaction — but the only thing that impressed me was the fame and the fortune, the excessive abundance of money that was just over the top. I’d get more in a tip than what people here make in a month.

“When we’re young, we revere these celebrities. We think everything they say is brilliant, we worship their opinions and would give anything to be in their proximity. But when you’re so close to them you start to realize, ‘who cares what they think?’ It was pretty disappointing, since I was a very impressionable young guy, hoping within the business to find substance, meaning, role models, value. But instead, I was thrown into a very selfish and narcissistic world, everyone out for me, me, me. There was also a lot of patting each other on back and taking care of each other, because they’re all connected by this mutual interest of success, and they need each other more than they need to compete with each other.”

In this world, the players were powerful, egocentric — and a lot of them were Jewish.

There were people in Jared’s orbit like Howard Rubenstein, the famed public relations strategist who led a boutique firm favored by media moguls and other high-profile figures, with clients like Mayor Abe Beame, the New York Yankees, the Metropolitan Opera, Donald Trump, and Rupert Murdoch. He built these people, and the world hung on their every word.

“A guy like me, who was also Jewish but without any Jewish identity whatsoever, might have wanted their fame and their money, but I couldn’t connect to their lives in a meaningful or inspirational way. I knew this wasn’t what being in the presence of greatness meant. I was living that life, but deep down I knew I was missing something even bigger.”

Jared was making so much money it felt like he was playing Monopoly. He bought a house and a brand new car with cash. During those years, he also had the luxury of being able to experiment with new types of art and created a signature art form, a kind of cross between photography and modern art, in which he’d take a series of photos of something innocuous, like a living room or his grandma’s Formica-topped Brooklyn kitchen, and create a puzzle, a kind of real-life moving collage out of them. His art took off and was featured in galleries around the Tristate area. Could life get any better?

Until one day, when he and a non-Jewish girl he was seeing were having a discussion about raising children, and she, easygoing as she was, said she’d have no problem raising kids both Jewish and Christian — a menorah in the windowsill and holiday tree.

“When she said that,” Jared recalls, “I suddenly thought to myself, ‘Wait, I’m Jewish! I didn’t even know what it meant, and I never even lit a menorah, but I knew I didn’t want to raise my kids with all that other stuff. I remembered how my grandmother used to take my hand and tell me, ‘Jared, marry a nice Jewish girl.’ And I realized, do I really want to marry a non-Jewish woman?”

I’m cutting all my earthly ties / Soaring to new heights / Surprise / Believe me / All that belittles belies / Saying my final goodbyes / Letting go / From deep inside / Where jealousy thrives

Jared broke up with the girl, and that undefined fuzzy emptiness he was feeling became more acute (“even though,” he admits, “the money and the glitz did a pretty good job of covering it up”). Meanwhile, he’d become friends with a Jewish guy named Brett Cohen (“those last names just don’t let you escape”). It was June 1997, and that weekend Brett was heading off to a Jewish camping shabbaton. He asked Jared to come along.

“As soon as I got there,” Jared relates, “I met the two fellows who were running it: Eric Gerstenfeld, Dovid Neiburg, and Yaakov Goldman. I was 34 years old, and within minutes I realized that the elusive something I’d wanted back when I was ten — I was seeing it now in front of me in real life. I never had Shabbos before, but we had Shabbos together, and I saw G-dliness. There was no turning back — it was just a matter of time.”

After that transformational Shabbos, Jared decided to spend Shabbos with observant families. He would drive from New Jersey to Queens every Friday, to families affiliated with the Jewish Heritage Center. “It was the first time I really saw how functional families interact with each other and what healthy marriages look like,” he admits. “I was very close to the world of the celebs, and when you’re so close, you really see the underbelly of this society — the competition, the lies, the deceit, the power struggles, and the egos. I realized that wasn’t the life I wanted.”

A year later, Jared stopped taking jobs on Shabbos, which meant severely cutting down his client base. He remembers the last over-the-top wedding he did before setting down his Shabbos-observant policy.

“It was for a woman I’d worked with before, who was getting married to the CEO of Lucent Technologies, a massive company at the time that was competing with the recently divested AT&T. The opulence was unimaginable,” Jared describes his initial meeting with these new clients. “The guy’s house was colossal, probably the most valuable real estate in New York, with several Rolls Royces and Ferraris parked in the massive carport out front. They hired me to do the wedding, a week-long affair in a luxury retreat in upstate New York. The job alone was $45,000, which included my own vacation. I’d be in the boat with them taking pictures, and in-between shoots I was going water skiing and playing ping pong, volleyball, and pool, walking around with my camera taking pictures a couple hours a day. I was there from Monday through Thursday and was back home Friday morning, so that worked out, but it was the beginning of the end.

“Remember that in this industry, everything happens on Friday nights and Saturdays — all the parties, all the jobs. Sunday’s the day they recuperate. So I went from the top of the industry to zero. Once people found out that I wasn’t available on Shabbos, it was like a domino effect — everything collapsed. I still had money, but I basically said goodbye to a business that I’d built up for more than 15 years. But I said, ‘Hashem, if You want me to keep Shabbos, I’m keeping Shabbos.’ I didn’t care.”

Jared started learning Torah with Rabbi Moshe Turk of the Jewish Heritage Center in Queens, became serious about his Yiddishkeit, and even started building up a Shabbos-observant business by moving into the Orthodox wedding circuit. And for the first time, he was even considering building a Jewish family.

“Because my parents got divorced in a way that for me was very messy and tragic, I never wanted to get married and have kids,” Jared says. “My own memories were too painful, sad, and disturbing, so my frame of reference had always been, ‘marriage, you’ve got to be kidding.’ But then I started becoming exposed to other families — happy, functional families — and I began to think that maybe it was something I could have too. Could I do it? Could this really be me? I’d always dreamed of it since I was a little boy but never believed it was within my reach.”

His new Orthodox friends believed in him though, and he was soon introduced to his future wife, geriatric social worker Liz Werner, from L.A. They got married in 2001.

“We started off married life in Passaic, but I was 38 years old and had basically just learned alef-beis,” Jared relates. “I told my wife, ‘Look, I never had a chance to learn in yeshivah. Maybe we could go to Israel for a few months so I could learn in yeshivah?’ Neither of us ever thought of living in Israel — it wasn’t on our radar — but we packed, and she said, ‘Let’s go.’

“I was learning at Darche Noam-Shapell’s, and a few months in, I told Liz, ‘You know, I’d really love to stay longer.’ She said, ‘Sure, why not? Anyway, what are we going back to?’ ”

They went back, packed up their things, and have been living in Jerusalem ever since. Liz found a job, and Jared reopened his business. Today their daughter and twin boys study in mainstream frum schools.

My courage is contagious / Spacious / Spreading out in stages / It supposes / Standing on tippy toes / With straight posture it poses / The questions it raises / Right under our noses / Slowing down / Smelling the roses / In and of itself it composes / Skipping no phases / Stumbling through mazes / Lumbering / Earning my heavenly wages

Photography, says Jared, is looking from the outside in, but throughout his life, there was always something on the inside that wanted to find expression as well. He began to paint when he was becoming frum in his late twenties — each work, he says, a spiritual expression of the journey he was going through. After settling down in Jerusalem, though, he stopped.

“I didn’t believe my art would be accepted in the frum world,” he says. “I didn’t think there was room for me to be unique. They’d probably think I was some crazy guy, some Andy Warhol wannabe. But with time I realized that everyone has a piece of themselves that they’d like to express more. Whether it’s cooking, crocheting, exercising, or whatever, everyone has a side that’s waiting to come out. For me, the photography did it to an extent, but that’s still from the outside in — and I also needed an expression from the inside out. The paintings help me comprehend my internal yearnings for spirituality and my relationship with Hashem. So I’m on this journey to find a way for my neshamah to express itself.”

Three years ago, with the encouragement of his wife, Jared took out his paints and canvases again. Some of the resulting works are on display at a Judaica gallery in Jerusalem, and one recently sold for thousands of dollars.

The title of his book, “Courageous Chicken,” basically sums up those yearnings and the internal conflicts that come with life-altering changes. Any change is scary, and for most of us, it’s easier stay where we are than to move forward to the unknown.

So how does a person do it, especially someone filled with fear and insecurity? “I’ve grappled with fear since I was a child, but what I discovered — through emunah, hard work, and taking risks, which is so against my nature with the fearful personality that I have and the insecurities I’ve dealt with — was that every time I put my hands out, I say, ‘G-d, You got this one.’ When you know, you know.”

Modern art might not be your thing, but the book, a showcase of his recent works and accompanying soul-baring verse, has the approbations of over a dozen rabbanim and mechanchim, including Rabbi Paysach Krohn, Rabbi Zev Leff, Rabbi Dr. Akiva Tatz, Rabbi Zecharia Wallerstein and others, giving their kosher stamp to a genre not familiar to most frum readers.

“What I’m trying to say in the book is that the courage to make any kind of change, even if it looks small, is something to be recognized and celebrated,” Jared says. “Every move we do is a huge move. So despite the fact that I’m such a chicken, I’ve used a lot of tools and walked through a lot of darkness. The more blockages we make, the more distant we are from Hashem and from the other people in our lives. When I was growing up, I didn’t understand this, but today, I so don’t want that separation.”

That’s one reason he’s off social media today, even at the expense of his business. He says it was too unhealthy, causing fragmentation and jealousy instead of boosting business in a positive way.

“I was using Facebook to boost my business until around five years ago, but it was horrible for me,” he says. “It was making me too competitive, too jealous, really bringing out my worst middos. It bombards you from every angle — you see these amazing posts and think, this person is so much better, richer, smarter, etcetera — and most of it is just sheker that people are buying into. I believe it’s a negative, dangerous, detrimental thing for everyone, fragmenting relationships and ruining real communication. This has nothing to do with religion, by the way. Kids no longer know how to talk to their friends, don’t know how to make eye contact. Our guests are always shocked that our kids actually talk to each other.”

Today, his role models are the rabbanim and mentors with whom he’s in regular contact, and he’s proud that his kids are growing up as frum Jews in the Holy City. Still, how does a person deal with past experiences, former lifestyles, regrets? For Jared Bernstein, it’s a choice to live in the present.

“I’ve done teshuvah for the past, and for sure I have my regrets,” he says, “but there comes a time when you have to close the chapter. I’m not cutting off that limb of my life — it’s a part of what makes me who I am — but at the same time, I don’t dwell on it. I’m taking the broken parts of me and putting the pieces back together, giving Hashem the most whole and perfect version of myself that I can. This book has been such a refuah for me, and as I’ve unlocked and freed that part of myself, I’m hoping it will help unlock others as well, to live a more internally honest and fulfilled life.”

Because honestly, isn’t there a bit of courageous chicken in all of us?

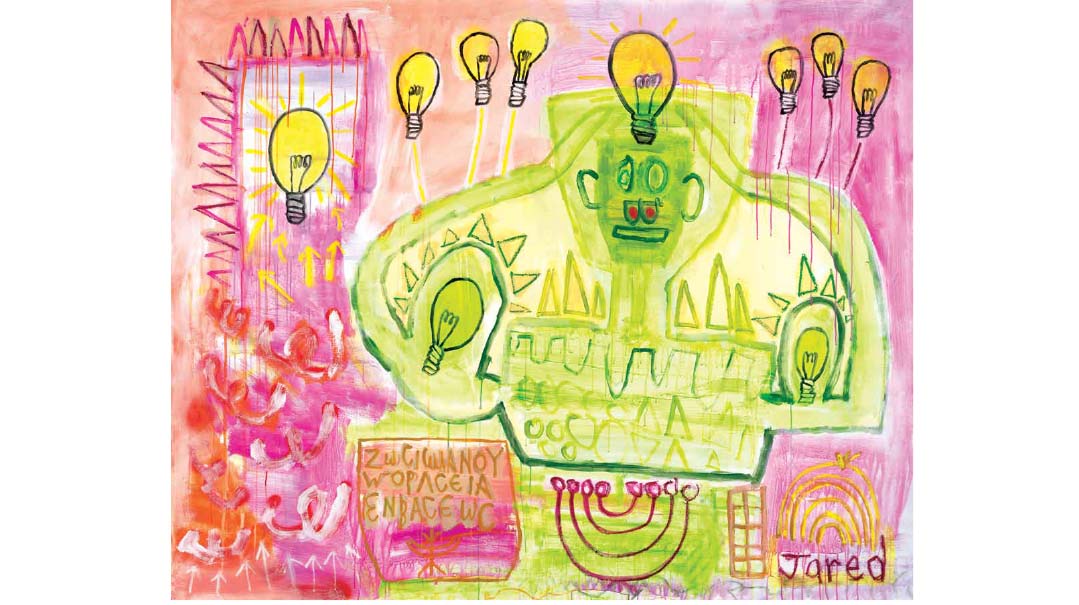

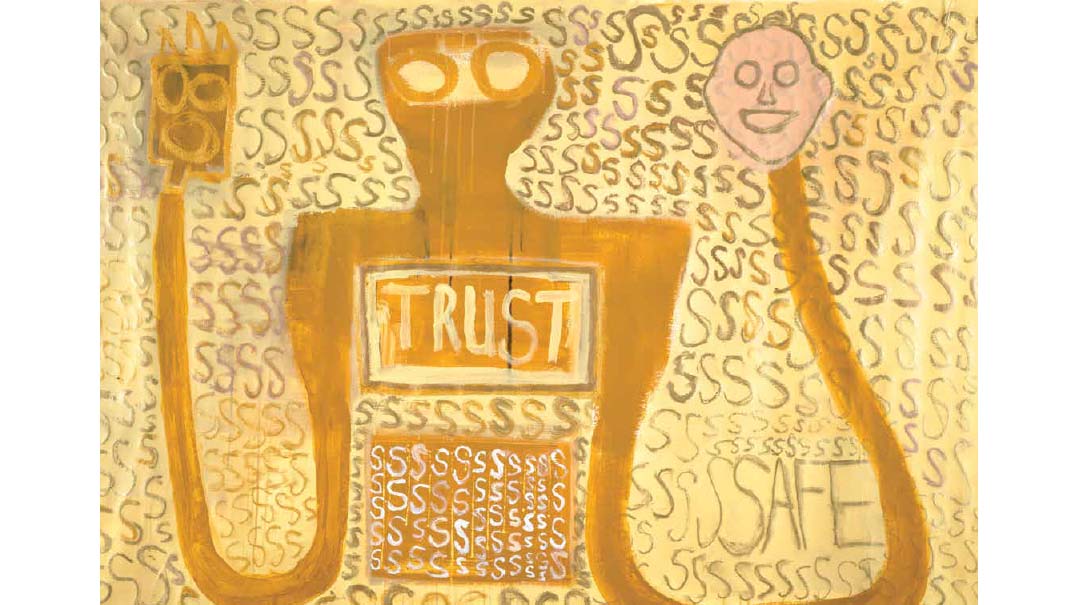

JARED BERNSTEIN’S GUIDE TO MODERN ART

If you’re a connoisseur of modern art, you’ll surely be intrigued by the gallery pictures displayed for the reading public in Courageous Chicken. But if you’re not, you might have a hard time figuring out why the noses are off-center, why people have sticks for arms, or why a mouth looks like a train-track grid. Jared isn’t fazed though — he’ll happily explain the parts of his neshamah that his paintbrush was expressing as he put hand to canvas.

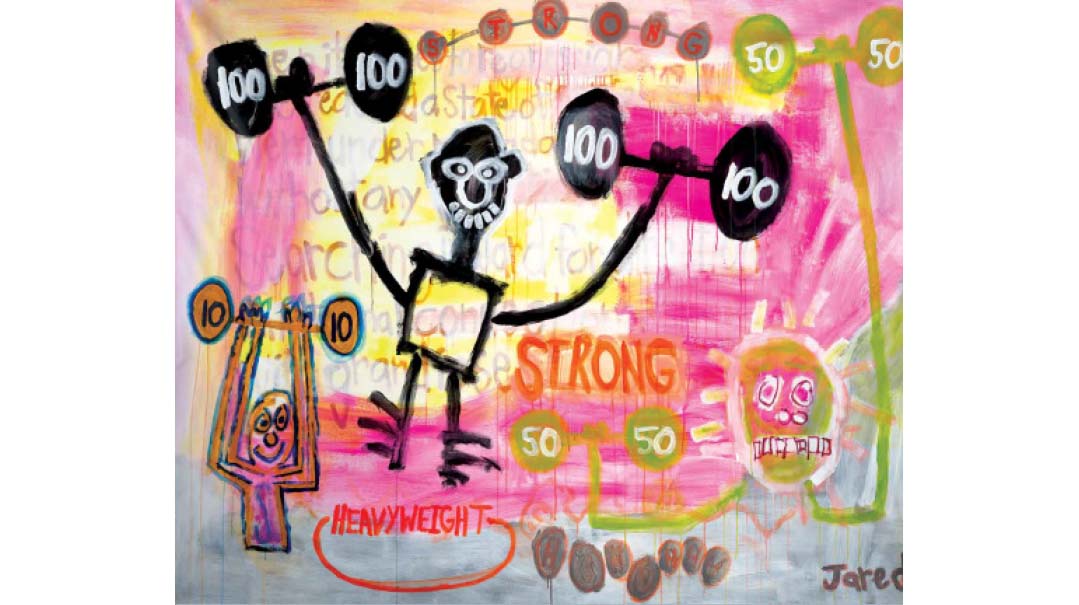

Take the picture “Dumbbells,” for example. An excerpt of the poem that accompanies it:

I’m just another extension of your reflection / a cog in Your creation / a proud projection / A man on a heavenly mission / Drifting in Your direction…. Please hold me tight / I need Your protection / Not to mention / I’m Your most treasured possession.

“This painting is a reminder for me, with the fellows pressing heavyweights, mid-weights and featherweights, about all the efforts I used to put in to the physicality of my life. ‘Dumbbells’ are barbells, but they’re also people who spend their whole lives working on their externalities, busy working out with their dumbbells. The poem drags in the other direction: We have to use this physical word but as a means to a spiritual end.”

Perhaps the most curious painting is the one that’s also the title of the book: What, exactly, is happening with this “Courageous Chicken?”

“I’m projecting out from a very deep place, a chicken. It’s scared, but once it comes out, it’s less scared,” Jared explains. “Next to the chicken is the warrior — I transform my fears and vulnerability to strength, like a warrior. The arrows represent the weapons used to break down the facade of someone, and the facade is what gets in the way of us getting real, of taking changes and taking risks. On the right are five sticks, like fingers, holding onto a ball of infinity, because once we’ve waged war on our fears, we really can stretch to infinity.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 888)

Oops! We could not locate your form.