Terms of the Deal

But this year that wasn’t what she heard. She heard hesitance and reluctance and then bitterness and resentment and anger

IT

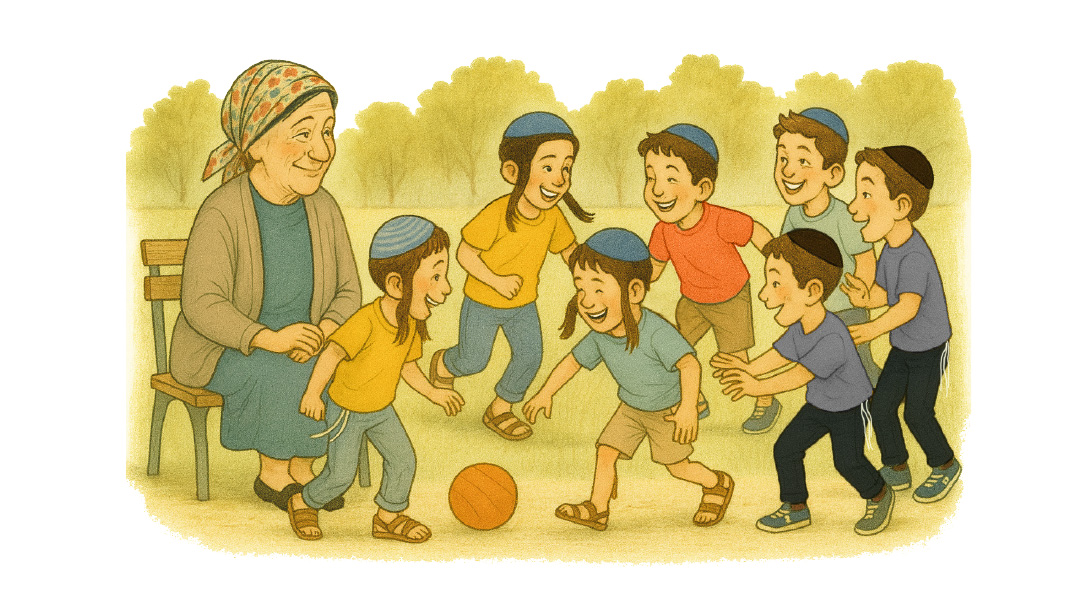

was summer vacation, and all the grandchildren were off from school. Even Yitzchak’s boys were off now from yeshivah, bein hazmanim they called it. Finally Savta Shlomit was going to have her yearly treat: a big family get-together in the park, followed by supper in her apartment. The kids would take out all those old toys she kept in wooden crates and spill them all over the floor. They’d build castles or mazes or cities out of the blocks and Lego and dream up characters to fill them. Their chatter and banter would rise up from the floor, a sweet backdrop to the adult conversations wafting from the couches and dining room table.

Savta loved to go all out for this vacation supper, preparing all her children’s favorite dishes. Though being the good children they were, they didn’t come empty-handed either. Yitzchak always brought a fragrant shepherd’s pie — Malka made an exceptionally good one, with layers of savory meat topped by swirls of creamy mashed potatoes, and a hint of nutmeg inside. Yoav brought bags of freshly roasted pitzuchim from his store: sunflower seeds and pumpkin seeds and salted peanuts and the freshest almonds in the country. And Yaron always brought his Adi’s famous mango mousse, made from the mangoes they grew in their own backyard. You could taste the sun in each bite, Savta Shlomit liked to say.

She’d been crowing extra loudly about the taste of the sun the last few years, hoping that Yaron wouldn’t notice how Yitzchak and his kids never finished the mousse to the end. Oh, they ate it, they exclaimed over it, they clearly relished the tropical treat. But somehow each one left a noticeable segment in the cobalt-tinted bowls she served it in (she could use disposables, like Orli always recommended, but the sunset yellow of the mousse looked so bright and pretty against the blue bowls). She suspected it had something to do with Yitzchak’s stringencies, all those complicated chumrot he and Malka had picked up over the years. Hopefully Yaron didn’t realize, hopefully Adi wasn’t insulted.

That’s the last thing she needed, for one of her children to feel slighted by the other.

Of course, when they were small, they fought plenty, but even when they hurt each other, they knew the force of their love far outweighed the pettiness of their quarrels. If a neighbor or classmate so much as threatened one of them, the other two would be there in a flash. One time she’d even gotten a complaint from Gveret Lilienblum down the street — your Yaron told my Adam that if he bothers Yoav again, he won’t be able to walk for a week — Savta Shlomit had made concerned noises, but inside she was proud of Yaron. That’s what it meant to be a brother. You can’t just go on with your life knowing someone is threatening your own flesh and blood.

Every year when she called to let them know about the get-together, they said of course, Ima, of course we’re coming. We can’t wait. All the kids say the summer get-together at Savta Shlomit is the highlight of the year. Malka’s shepherd’s pie and Yoav’s pitzuchim and Adi’s mango mousse… we look forward to them the whole year. But of course, not as much as Ima’s food, Ima’s kebabs and chicken tagine, the roasted peppers and nut-studded couscous flavored with a mother’s love.

First, of course, she had to get through Tishah B’Av, with all that sad talk of the widow that was Yerushalayim, weeping in a shattered city, abandoned and ashamed, missing her children. She didn’t much like to think about that woman. Her coping method since David’s passing was to keep moving forward, not to linger on the aloneness, like she was forced to do on Tishah B’Av.

The day was long and hot but then it was over, and it was time to plan. Wednesday would be a good day for the get-together, Savta thought. Thursday, things got busy in Yoav’s store. She circled the date on her calendar and started working on her shopping list. She would need ground meat and chicken thighs, sweet peppers and hot peppers, fresh lemons and lots of garlic. And then, for after the meal, some dates and a big watermelon — of course from the store with the hechsher that Yitzchak liked, even if it was four more stops on the bus. That’s what you do for your family, that’s what you do when you want all your children to feel they can always come home. And doesn’t every mother want that, doesn’t every mother whose home is empty, whose nest is quiet, dream of a big wave of chatter and laughter and conversation and maybe even some debate cresting through the house as the children come back?

So she started her phone calls. Yoav, she said, put it down on your calendar: Wednesday. You and Orli and all the kids. What could be better, an afternoon in the park and then a good filling supper with your brothers. After all those weeks in miluim, I’m sure you could use some time relaxing on the grass, without any booms or bombs disturbing you. You deserve to just stretch out and have some peace.

Yaron, she said, I hope we’ll see you on Wednesday. You’re not giving any classes in the university then, right? I know Adi’s busy at work, but this will help her. She won’t have to make arrangements for the kids, she won’t have to cook. And of course I’ll pack up a big tray of leftovers for the next day’s suppers too. She works so hard, Adi. Such a good wife.

Yitzchak, she said, Wednesday is the day. You can all come, right? Even the big boys, it’s bein hazmanim for them. We’ll start in the park, the little ones can get out their energy, and then everyone will come here to eat. And of course I’ll do the shopping in that store you like, the one with the good hechsherim, like always. Exactly the same food you buy at home.

And she waited for them all to say of course Ima, of course we’re coming, what could be better than an afternoon back home with the family, and with your cooking, with all that neshamah in every bite.

But this year that wasn’t what she heard. She heard hesitance and reluctance and then bitterness and resentment and anger.

The first phone call was hard. Yoav’s Orli was finished, he explained. Too finished to think about driving over to Savta. This last round of miluim had just about broken her — dealing with the house and the kids and the shopping and the bombs from Iran all alone, night after lonely night. She couldn’t just sit in the park, on a picnic bench, next to Malka and her holier-than-thou daughters who didn’t know what it meant to really sacrifice, to risk the lives and limbs of the people you loved most so other Jews could be safe. And not just lives, but your livelihood, too — did Yitzchak and Malka think the store just took care of it itself while Yoav was in miluim? Did they think his bank account just kept itself full? Oh, of course they considered themselves very Jewish, very holy. But how Jewish was it to ignore their own brother’s suffering, to see their people in danger, and not take on some of the load?

You know, Ima, Yoav reminded her, to us it’s clear that this land is ours, but our cousins in Iran and Lebanon and Syria and Gaza and right here in Yehudah and Shomron don’t agree. It’s a miracle that we can make a life for ourselves in the pieces of this patchwork we do control. You know about all the restive little villages surrounding our yishuv, the green license plates on the roads around us. If we don’t fight, if we don’t keep constant guard, we’ll lose what we do have. Maybe the Danes get to live in Denmark just because. And the Brazilians, no one questions whether they have a right to their own land. But us Jews, we don’t get to live here for free.

Savta Shlomit hesitated before dialing Yaron. He was always so busy with important things. She knew he was spending every Motzaei Shabbat at those protests in Tel Aviv, waving photos of those poor poor hostages and yelling that Bibi was to blame for this terrible situation, that it was time for him to quit and stop sending people into the bog of Gaza just to prop up his career. Was he right? Was he wrong? She didn’t know Bibi, she wasn’t one to say. She knew their enemies, though — her family had lived in their dark shadow for generations — and she had a funny feeling that the problem lay more on that side of the fence than on this side.

She tried Yaron anyway. And she tried not to cringe when he said, I don’t know if I’m going to be able to make it this year. I have a big meeting, we just put together this humanitarian petition, and we want to strategize so we can get signatures from prominent people of the arts — you know, musicians and artists and movie producers and celebrities and influencers across the world.

Let me tell you something, Ima, Yaron explained patiently, professorially, probably the same way he talked to his students. The only reason we have a country is because the Western world supports it. We can’t risk losing that support. We have to show those Western countries that we’re still civilized people, that we don’t approve of sieges or the starvation of innocent children. We need to get out the message that we’re the good guys in this war. The way things work for us Jews is that we have to prove ourselves, prove that we deserve to have a country. We don’t get to live here for free.

Yitzchak, it turned out, was willing to come, but he couldn’t bring his older boys. They’d been told to avoid some highways and the entrances to any major cities. Word on the street was that the military police had set up checkpoints to apprehend yeshivah boys who hadn’t reported to the draft offices as they’d been commanded to. Eliyahu, his oldest, had a friend who’d been arrested. Could she imagine that? Could anyone imagine that? A Jewish country, arresting boys for doing the most Jewish thing in the world — learning Torah. What a blow, what a low point for the state and for the nation. Malka didn’t want to take any chances; she couldn’t handle the thought of her son in jail.

Savta Shlomit wasn’t sure what to say to that. She didn’t understand all of Yitzchak’s decisions. Back when she was a girl, even the chassidim in Bnei Brak had helped defend their fragile country. But this was a new world, and Yitzchak said it was a new army, an army that prioritized a lot of things beyond keeping the country safe. He couldn’t uproot his boys, his still-blooming flowers, from their soil and hand them over to be pressed, crushed, banged into some new, contorted shape. He couldn’t entrust his children to an institution that had so dismally failed at its promises, an institution that had knowingly invited impurity and indecency into its operations, endangering not just the lives but the very souls of its soldiers, flouting the command to keep its camp holy so as to merit Divine protection.

Don’t you see the pattern, Yitzchak asked. The more this country delegitimizes the lomdei Torah, the more the world questions its right to exist. You know, Ima, he said sadly, this land, it’s ours only if we earn it. It hates impurity, it reviles immorality. We don’t get to live here for free.

Savta Shlomit put down the phone and swallowed hard. She opened the refrigerator and looked at the ground meat for the keftah, the chicken thighs for the tagine, the lemons waiting to be juiced. She fingered those perfect, unblemished peppers she’d picked out so carefully. How can one set of parents, she wondered, produce children who agree their Land demands something of them — that some ancient ancestral covenant is at play — yet when it comes down to the terms of that heavenly deal, agree on precisely nothing? How is it that children who share a childhood and gene pool and a homeland and mortal enemies can’t even sit together around a shared table?

Slowly, sadly, she took out the meat and chicken. There was nothing to be done for the peppers; soon enough they would wrinkle and soften into an inedible mess. She opened the freezer and stowed the meat and chicken inside. And she thought of that widow she’d just heard the baal korei chanting about during the lament of Eichah — the bereft woman sitting alone, with her tears on her cheeks, waiting, longing, for her children to come back home.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1074)

Oops! We could not locate your form.