Just Fine

“I’m worried about his ability to be empathetic,” Raizy says slowly, still reading through the résumé. “To be caring, to anticipate someone else’s needs”

“I

’m wondering if we should consult with a professional,” Raizy says. It’s the third time she’s brought this up.

“Tell me what I’m missing here. Everything is fine for 22 years and suddenly you’re looking to slap a label on the boy five minutes before he starts shidduchim?” Dovi presses his fingers down on the kitchen table. “I’d say — and Raizy, I mean this in the nicest way possible — I’d say you’re the one with the problem.”

Raizy lets the dig slide. Maybe he’s right. Maybe she’s the one who is damaged? Pulling her laptop closer, she clicks on the file named “Yossi Suggestions.”

“Do you need him to stay your little yingele?” Dovi continues his barrage, pacing now. “Is that what this is about? You don’t want him to move on?”

“Chas víshalom,” Raizy mumbles.

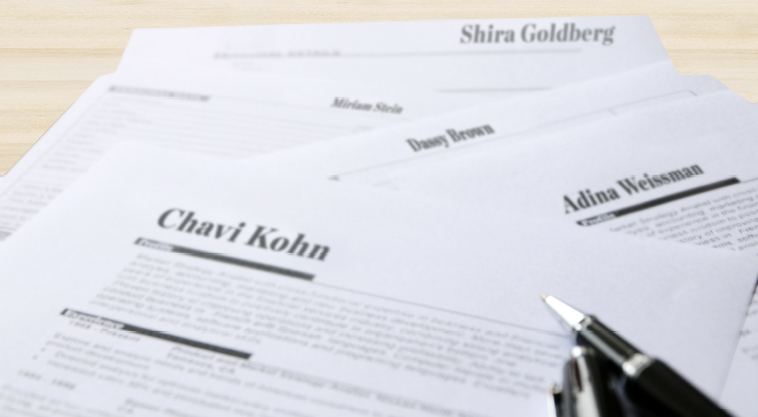

Chaya Leah Blumenberger. 19. BJJ. She scrolls through the résumé. Enjoys reading and nature. Also loves spending time with friends. Just like every other résumé in the file. Every girl hitting the same spot on the map: somewhere between an extrovert and introvert. Perfectly balanced. Perfect grades, perfect families, perfect hobbies. All searching for that perfect masmid. Not a flaw in the lot.

“We have an achrayus, Dovi.”

“Of course we have an achrayus. To not blow our son’s future to smithereens by creating problems where they don’t exist. You know what the Rosh Yeshivah said to me last time I popped in. Remember?”

“That Yossi’s one of the brightest minds that ever came through the yeshivah. I know, Dovi. I never questioned his intellect. In fact—”

“You know how many girls would be thrilled to do a shidduch with a boy who is well on his way to finishing Shas?”

“Dovi—”

“And don’t get me started on his middos. The only one of our kids who never leaves a mess, makes his bed every day. A dream roommate, that’s what his roommates all report. A dream, Raizy.”

“Roommates aren’t wives,” Raizy snaps back. “And let’s not pretend this is the first time I’ve worried.”

“Because he hated sports?” Dovi’s face turns dark. “Because he wasn’t the most popular kid in fifth grade? You wanted to make mountains out of molehills. You wanted to package shy and eidel as some sort of fad disorder. Twenty years ago boys were allowed to be quiet and a little nerdy. Now? You have a boy who likes to read and build model airplanes and boom — he’s got a disorder.”

Raizy opens another file.

Bracha Blima (Gittel Shaindel) Rosenshterner. She blinks. Did someone really name their child that? She keeps scrolling. Ah. She’s the youngest. Eight boys on top of her.

“I’m worried about his ability to be empathetic,” Raizy says slowly, still reading through the résumé? “To be caring, to anticipate someone else’s needs. You know after Devorah gave birth to Chanie he never even called to say mazel tov. Can you imagine? His own sister!”

“He’s a boy, Raizy! Boys don’t make post-birth mazel tov calls.”

“And that time my father bought him a sefer last Pesach and instead of saying thank you like a mensch, he said, ‘Oh, I have a copy of this already.’ I was mortified! It’s like, he has no idea how to answer sensitively!”

“Men are not women — they aren’t sensitive. He was just being honest.” Dovi shrugs. “Give me ten yeshivish yeshivah guys and I guarantee every one of them will be rude in some way. It’s the way it is. Not being polished doesn’t make someone a bad person.”

“And how is he going to schmooze with a wife at night? I can barely get a few sentences out of him!”

Dovi stops his pacing, meets her eye. “Roommates aren’t wives — but neither are mothers, Raizy. He’ll be different with his wife.”

He lets out a little sigh. “I get it. He’s your only son. I’m sure every mother is worried sick before her son starts shidduchim.” Dovi motions to the computer screen. “Take a deep breath — and choose a girl for him to date. Other boys his age are knee-deep and he hasn’t gone out once. I’m going to the airport, his flight should be landing any minute.”

Once he leaves, Raizy slumps down in her chair, depleted.

It was Devorah who’d confirmed her fears. Her oldest daughter, married a little over a year. She’d called her two weeks before to discuss Yossi’s shidduchim and her questions were met with complete silence.

“It’s just… I can’t imagine Yossi married.”

“Why?” Raizy had urged, her mouth going dry. “He’s capable, smart…” She trailed off.

“He’s not warm,” Devorah sputtered at last.

Raizy let the sentiment somersault through her brain in the weeks since. It didn’t bother her that Yossi wasn’t particularly close with his sisters. The question in her mind was whether or not he was capable of warmth. Of empathizing. Of considering someone else before himself.

“I’m scared his wife is going to come down with the flu and he’ll tell her he can’t do playgroup pickup because he’ll have to daven a later Minchah. You know how he gets with his schedule,” she’d said to Dovi the night before.

Dovi had rolled his eyes but didn’t dispute the notion. “You realize you’re stressing out about a hypothetical wife, suffering from a hypothetical disease, right? Please, Raizy. Please step into reality.”

Yossi had always been quirky. Gifted, he always received top grades. He had friends — never a plethora, but some. “He doesn’t seem lonely, just keeps to himself,” his rebbeim would answer when Raizy voiced her concerns. Of course, Yossi had his moments where he wreaked utter havoc, just like any child. He hated baths as a child, refused to join the family on many of their Chol Hamoed trips as a preteen. And Raizy had to drag him to six stores before he found a bar mitzvah suit that fit comfortably. On the flip side, since then, buying a suit for him was simple as long as Raizy made sure to get the same brand suit and shirts and shoes every time. Yossi was utterly easy to please.

Still, Raizy worried. At six he told Raizy’s mother her chicken soup tasted like feet (“It’s so refreshing that he tells the truth,” Dovi had proclaimed). At nine, he could tell her how many muscles it took to hug someone, but squirmed away when she actually tried to hug him (“No nine-year-old boy on earth wants his parents to hug him,” Dovi had exclaimed). At eleven the school called, saying Yossi wouldn’t participate in gym class (“Not every kid is an athlete, I personally hated sports,” Dovi had reassured her).

After his bar mitzvah, Yossi went from pouring over posters of classic cars to putting all his energy into his learning. The Masmid. That became his identity. And now, the illui of the yeshivah is on the market, shadchanim are calling left and right, and all Raizy can think about is his poor, flu-ridden wife trying to pick up the kids from playgroup.

“He’s never had to be flexible, Raizy.” Dovi said, over and over. “That doesn’t mean he’s not capable. He gets his drive from me. This business, the one that allows us to go to Israel for Succos, to stay in the Waldorf, to redo the house — that’s because of my drive. And Yossi has that same drive. Only his mind is 100 times what mine is. His future is so bright Raizy, we’re talking rosh yeshivah material here.”

She’d broken after that little speech last night. She’d let the fear out of its cage, let her apprehension explode everywhere. “I’m afraid he’ll get married. And he won’t be compassionate enough. And she’ll hate us, his wife. Forever. She’ll feel duped.”

“You cannot fault a normal boy for being a normal boy, Raizy. Enough.”

And now he is on his way home for Shabbos. And she was supposed to pick out the best wife candidate for her son who she still, after all this time, doesn’t really understand. And she’s wondering what normal is anyway. If there are measurable parameters of normalcy. If that word even has a definition. And mostly, she cannot decide if she should speak to Yossi about her worries, or keep them to herself.

“Hi.”

“Yossi!” She stands up and walks over, offers him a little hug.

Do I say something? Do I sit him down and explain my worries? Do I ask him if he feels ready to be in such a complex relationship? Do I ignore it all and let life happen?

Dovi seems to read her mind. “He. Is. Fine,” he says after Yossi heads upstairs to put his bag down. “You’re worried, but he’s fine. Trust me.”

And because she so badly wants to trust something other than her own gut, she agrees.

She piles chicken and potatoes onto Corelle, sets it on the table, asks Yossi about his flight, yeshivah, chavrusas.

He’s fine, she repeats to herself. He’s a totally normal young man and I’m a totally normal worried mother and we all need to just breathe.

She watches as he clears his plate, thanks her, heads to the dining room table with a sefer. She follows.

“Yossi I wanted to talk to you. About shidduchim. Baruch Hashem, we’ve received a lot of names—”

He looks up. “I actually wanted to talk to you, too. I think I’d like to push off dating for another six months,” he says, matter-of-factly.

She’s startled. “But… why?”

He stares down at his sefer, stays very quiet. She waits, knowing his particular habit for thinking before answering.

Waits.

And waits. Until she feels terror crawling from her fingers to her heart.

“I know normal guys my age are ready,” he finally says. “But I’m—” he lets the sentence hang.

Heat floods Raizy’s face. Twenty-two years of being Yossi’s mother rushes through her, a familiar frantic need to protect him.

“What do you mean normal guys? You’re normal, Yossi. You’re incredible, brilliant, and respectful and—”

Yossi looks away, squeezes one hand with the other, and Raizy knows she’s done something wrong. Denied her son’s truth one too many times. She stops talking and sits down next to him.

“I’ve been working with someone.” Yossi says at last.

Raizy blinks. “What…”

“A therapist that works with people like me.”

“People like you?”

“An Asperger’s syndrome therapist.” He says it so suddenly she has no time to prepare for impact. The words crash through her, shattering the glass encasement, leaving her heart thumping and exposed. And under the shards at her feet — there is relief.

She doesn’t move.

“His name is Fried. Robert Fried. He thinks I could use some more time to acquire additional tools. That’s the way he put it.”

“Why didn’t you tell me?” she whispers.

“You didn’t ask.”

“How long—”

“Close to two years. It started when my chavrusa Ari Feinwax got engaged. The night of the vort I was in the beis medrash learning. Rabbi Diamond, the mashgiach, came over and asked me why I wasn’t at my chavrusa’s vort. I told him the truth — that Ari had told me I didn’t have to come. He knew I didn’t like missing night seder, so he told me not to trouble myself.

“Rabbi Diamond explained to me that sometimes people say one thing, but really mean something else. And he and I realized, I don’t… I just don’t have a sense of what people are really saying. There are social rules that regular people understand intuitively that I need to learn. Fried’s been teaching me a lot about reading people, understanding them, and I think it’s important that I continue for a while.”

Raizy only trusts herself to nod. The million questions ricocheting through her brain will have to wait because the least she can do is accept this information without bombarding him with questions. The least she can do. The very least.

Dovi finds her an hour later in their room, staring out the window, eyes wide. She is very small, very still, tangled and tethered in regret, the word neglect strangling her.

“Had a schmooze with Yossi?”

She nods.

“And he’s fine, right? I told you,” Dovi says confidently

She thinks about this for a moment. “He is fine,” she says in a shaky voice, then lets out a harsh laugh because somehow that’s the truth.

She takes a long ragged breath.

“He’s fine. But you weren’t right, Dovi. Sit down, we need to talk.”

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 616)

Oops! We could not locate your form.