Four decades later, those classics have stuck

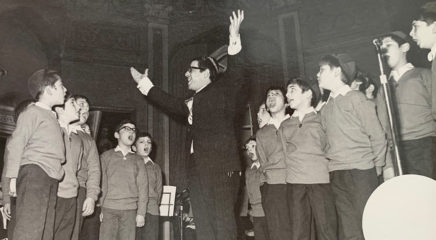

Rabbi Label Sharfman is the founder and dean of Bnot Torah Institute, better known as “Sharfman’s” in Jerusalem, and Abie Rotenberg is — well, he’s Abie Rotenberg. But back in the 1970s, they were chavrusas in the beis medrash of Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim in Forest Hills.

Label Sharfman had sung on the wildly popular Rabbis’ Sons albums — also conceived at Yeshivas Chofetz Chaim by Rabbi Baruch Chait — a few years before. One afternoon in Elul, Abie mentioned that he had composed a few songs, and asked Label if he would be interested in working together to produce an album. Despite a conspicuous lack of expertise and experience — Label had sung on the Rabbis’ Sons, but had nothing to do with production — the young pair was determined to inspire people with genuine Jewish music.

“Our vision was to produce real Jewish music, not bubblegum music,” Rabbi Sharfman remembers.

Rabbi Sharfman appropriately conceived the album name Dveykus LaHashem, which was shortened to the more catchy Dveykus — which, four decades later, would still capture the spirit of those yeshivah days. The Rosh Yeshivah didn’t mind the boys’ musical pursuits, as long as they stuck to their sedorim.

Caught by Surprise

Mutti Parnes z”l was the production consultant for Dveykus I, finding musicians, arranging studio time, and helping the project get off the ground.(He was succeeded by Rabbi Mutty Greenberger on following albums.) It was finally ready for release close to Pesach 1974. (Remember those unforgettable classics — the original “Lev Tahor,” “Hinei Yamim Ba’im,” and that first slow “Kah Ribon”?)

The finished product took even Label by surprise. “I was out of commission for a few weeks while the music was recorded for Dveykus I. When I heard it — Abie sent me a tape — it blew me away. I’d had no idea what was in his mind. People knew he was musical, but I couldn’t believe he was responsible for the depth of the music on the album. He was in his early twenties, it was his first real musical project, and those arrangements shone. He was the musical genius behind the series.”

Subsequent Dveykus albums were released in 1976, 1980, 1990, 1995, and 2000. Will there be another? “We haven’t given up,” says Rabbi Sharfman, “but Abie lives in Toronto, and I live in Yerushalayim. And we’re both very busy people.”

All the Dveykus albums were a collaboration between lead vocalist Label Sharfman and composer and arranger Abie Rotenberg, joined by guest artists Yussi Sonnenblick (the child soloist from the early Pirchei albums, who became famous for his “Eilecha Hashem Ekra” solo), Rivie Schwebel, and Elli Kranzler.

What Did They Sing Before?

Like most chassidic music, Dveykus songs were drawn from pesukim or from davening, with one notable exception: the moving Yiddish ode to Jewish suffering, “In a Vinkele Shtait… Tatteh, Tatteh,” composed by Rabbi Menachem Davidowitz, rosh yeshivah of Chofetz Chaim in Rochester. It was first recorded on Dveykus II.

Abie’s talent would continue to surprise even Rabbi Sharfman, his closest collaborator. “In 1980, I was writing the notes for the back of the Dveykus III album — the source for each pasuk and the composer of each song. For ‘Ve’li’Yerushalayim,’ I wrote ‘Traditional.’ Abie later told me that he had written it. I was shocked. When he had taught me the song, I thought it was a classic niggun from the 1800s.” Not so unfounded. In the end, it’s become a genuine classic.

Dveykus songs would become the mainstays of both Bais Yaakov and NCSY Shabbatons and kumzitzes. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, songs like “Yehi Shalom Becheilech,” “Bo’ee Beshalom” (“ay lay lay lecha dodi, ay lay lay likras kallah…”), and “Naar Hayisi” echoed around camp fires and school and shul halls. “Hinei Keil Yeshuasi” became the mainstay of Havdalah ceremonies. Says Rabbi Sharfman, “One NCSY director told me that one of his kids asked ‘What did they use to sing before Dveykus?’ ”

Rabbi Sharfman remembers one miscalculation. “Dveykus 5 was a Shabbos-themed album, but we didn’t write the word ‘Shabbos’ on the jacket. I think people bought it, expecting more of the same Dveykus style, and then it begins with ‘Shalom Aleichem.’ Kind of unexpected, and maybe that’s why most of the songs never became widely known.”

Of all those dozens of songs, Rabbi Sharfman says the early “Lev Tahor” will always be special. And another favorite is “Ani Maamin ShehaBorei Yisborach Shemo” from Dveykus 4. “Abie wrote the music, which is outstanding, and I put the words of the Rambam to it. Most ‘Ani Maamin’ songs are about Mashiach. This was something different — about the fundamental cornerstone of our emunah.” (Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 698)