Sweetening the Bitter Waters

They faced the unthinkable twice,and then the Holmans turned grief into giving

Sometimes Hashem sends tests that are excruciatingly painful. Yet in the case of certain people, they bring out strengths that no one, not even themselves, could ever have anticipated. The Holman family of Far Rockaway and their daughter Miriam a”h bear witness to this: They faced tremendous suffering and loss with faith and courage, and transformed their grief into initiatives to help others.

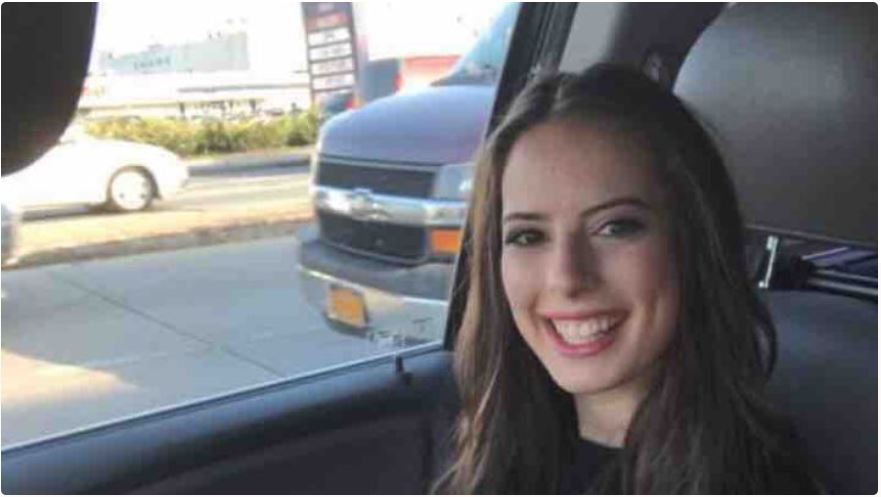

Miriam was nifteres on January 30, 2018 (14 Shevat 5778). The Holmans acknowledge that the name Miriam translates as “bitter waters.” Yet, like Miriam haNeviah, she took bitter waters and made them sweet for everyone around her. “She took what was bitter in her own life, and used it to reach out to others,” her father, Glen (Zelig Shaul) says.

Miriam had been deeply influenced by the family’s first bout of tragedy, over ten years earlier. In 1998, her sister, Nechama Liba, three years older than her, was diagnosed at age five with an extremely rare disease. After struggling for six years, Nechama Liba passed away three days before she turned 11.

“Nechama Liba was an old soul,” recalls Glen, who meets us at the home of his neighbor, Mishpacha writer Chaia Frishman. “Even when she was sick, she’d try to be b’simchah. She smiled just a few moments before she passed away. That was a driving example for Miriam when she became ill.”

“Nechama Liba was like a wise old woman in a child’s body,” Chaia concurs. “She was so mature, even regal, for a child.”

Nechama Liba’s death was a bitter loss, and as Glen and his wife Saguite struggled to pick up the pieces of their broken hearts, they were persuaded to attend a Chai Lifeline retreat that October. It was a powerful and beneficial experience, and when they returned, they found themselves wishing Nechama Liba’s siblings could have benefited from a similar experience.

They decided to organize an entire weekend for bereaved families, which became known as the Holman Family Retreat. They committed to raising all the funds and planning the entire weekend, A to Z, themselves. The weekends became a yearly event, and Miriam was always heavily involved in the planning.

Glen, who is trained as a licensed social worker specializing in bereavement, says those weekends are designed to accommodate a broad range of approaches to grief. “Grief is as individual as people are,” he explains. “Some people want to shut it out and not deal with it at all. If you try to force those people into therapy sessions, you’ll do more harm than good.”

The retreats offer plenty of fun, non-bereavement-centered activities, from motorcycle rides to art to Pirchei and Bnos groups and music. But those who want to speak about their feelings and receive guidance and empathy can participate in the therapeutic sessions.

Oops! We could not locate your form.