Still Before My Eyes

The only living survivor of the Babi Yar massacre says not a day goes by that he doesn’t remember. That’s why it took him decades to reveal his Jewish identity

As told to Noach Paley

In a park outside one of the Soviet immigrant-populated buildings in the heart of old Beit Shemesh, children play happily — but inside and up a flight of stairs, the atmosphere suddenly becomes heavy. A friendly white-haired woman opens the door, welcoming me into a small living room — the old black-and-white pictures on the wall and the red-patterned rug and matching sofa cover giving the room a distinct Russian energy. Michael Sidko, 85, quite dapper in a blazer with a row of Soviet military medals pinned to the lapels, listens to the squeals and chatter from the window, but there is no laughter in his eyes as he recounts his story. In fact, his are probably the saddest eyes I’ve ever seen.

Michael Sidko is the last known living survivor of the Babi Yar massacre, the last pair of eyes to have witnessed the killing of over 33,700 Jews of Kiev in the Babi Yar ravine during two bloody, gruesome days in September 1941.

It’s been over 80 years of buried memories, but now, he’s agreed to talk.

“People in this generation don’t believe me anymore,” he says. Michael might be in Beit Shemesh, but his heart is still there, in that cursed mass grave. “Maybe a few old people who are still alive and who survived the war. The others can’t fathom that things like that could happen in this world between people. In 20 years, when none of us survivors are here anymore, who will testify to the truth?”

Michael was born in Kiev in 1936. His grandfather, Rabbi Yudke Ruchkin, was a rav in Zhitomir, but Communism was wreaking havoc on the Jewish identity of the young people. Michael’s mother was one casualty of this new world order. She was married to a Jew in 1928, and bore a son, Grisha. Later, she divorced and married a local Ukrainian gentile in Kiev. They had three more children, Michael, Clara, and baby Volodya.

Here is Michael Sidko’s account:

We lived at Zhelanskaya 41, a large building with 50 apartments. Half of Kiev was Jewish, but it was hard to find Jews who observed mitzvos. We, for example, knew nothing about Judaism. Our father was Ukrainian, and we didn’t think we were any different. In June 1941, the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union and in Kiev, people understood that within a short time the Nazis would reach the city. Thousands fled deeper into Russia, and in our house, my parents also decided to escape. We packed up our bags and set out for the train station — Grisha, me, Clara, the baby, and our parents.

The station wasn’t far from our house, but when we got there, Grisha suddenly remembered that he had forgotten to open the door to his cage of pigeons.

“I have to run back, or the pigeons will die,” he pleaded.

And he began to run home. A minute later the train arrived. It was the last train that was able to leave Kiev before the Nazis arrived. My father pressed us to board — “Grisha will manage,” he said of his Jewish stepson — but my mother cried that she wasn’t leaving him alone. The train left, with my father on it. The rest of us returned home to the pigeons, which, in retrospect, turned out to have rendered our family’s death sentence.

On September 19, 1941, the Nazis marched into Kiev. It was captured easily by the German Sixth Army, and they established their central headquarters in the middle of the city, very close to our building. On September 24, five days after the Nazis invaded, an explosion rocked their headquarters, and afterward the entire area was closed off and civilians were detained for questioning. In the subsequent days more bombs went off, harming and killing many Germans and Ukrainian citizens. The bombs were set off by a group of NKVD operatives who remained in occupied Kiev to sabotage the Nazi forces, but the Nazis didn’t really look too hard to find the culprits — they retaliated another way, more in line with their ideology: the immediate liquidation of Kiev’s Jews.

On September 26, large announcements were posted on the walls of the buildings: “All the Jews living in Kiev and its environs must report at 8 a.m., Monday, September 29, at the corner of Melnikova and Dokterivskaya Streets (near the cemetery). Bring documents, money, valuables, warm clothes, and linen. Any Jews who do not follow this order and are found anywhere else will be shot.”

The Babi Yar ravine was on the outskirts of the city, behind the Jewish cemetery, just four blocks from our home. On Monday morning, we began to march, with thousands of other men, women and children, young and old, including babies in carriages. But in the middle of the way, our neighbor saw us.

“What are you doing here? Go home right away!” she told my mother. “You are not considered Jews. Your husband is Ukrainian. Go back quickly!”

My mother turned around and we returned to our building.

But the next morning, the Ukrainian police banged at the door. They grabbed us and threw us outside.

“Stinking Jews, you need to die!” they screamed.

It turned out that the gentile street cleaner had noticed us going back and ran to tell the Nazis, who paid for every such piece of information. It was September 30, the second day of the massacre. We came to the gathering area near the cemetery — it was surrounded by a barbed wire fence. The Nazis stood around us together with Ukrainian police, who were in total collaboration with them. The policemen shouted at us to leave all our bags and personal possessions. In the background, they played raucous music, which just added to the confusion. We passed the first checkpoint, and then came the point where we had to be separated. Men to one side, women to the other, children in a third place. I was then five years old. Grisha was 13.

“Watch over Michael,” my mother said to him tearfully. “You are of one blood.”

Beyond the second barrier was the path that led to the death pits. I remember an old lady crying to the policemen to let her pass because her family had already gone through. Grisha and I stood in the children’s area, as our mother, Clara, and Volodya were on the other side. Suddenly, four-year-old Clara noticed us and began to run in our direction. The Ukrainian policeman standing closest whacked her on the head with the butt of his gun. Clara fell to the ground, and then he put his boot on her neck and strangled her. My mother, watching this, fainted, and fell down together with four-month-old Volodya. That Ukrainian beast continued to trample Volodya, and killed him as well.

At this point, my mother tried to get up, but it was only for a moment. A hail of bullets brought a quick death. The Ukrainian soldiers took all three of them by the legs and flung them into the pit. Grisha and I stood rooted to our places. We saw it all. In less than a minute, we had lost my mother, sister, and brother.

Grisha pushed me to the ground and lay on top of me until nightfall. All the Jews who were with us had already been murdered. Within two days, 33,771 Jews were slaughtered. We had no idea what to do. We just stood there in the cold darkness, about a hundred Jewish children who’d somehow evaded the bullets. Their plan was to take us to a children’s hospital in Kiev and to conduct medical experiments on us.

There was one guard who raised his arm and told us, “Run, get away from here, all of you!”

So we did, everyone scattering in a different direction. I gripped Grisha’s hand and we ran back to our house. It was ransacked, pillaged — the neighbors had looted everything worth anything. We went down to the basement under the building and hid there. We were terrified. We had nowhere to go. We sat silently, calculating our next steps. At night we went out to try to find some food.

After a few days, the policemen returned — they knew we were hiding in the basement of the building. It was again the street cleaner who had reported where all the Jewish children were hiding. They took us to the police station and threw us into a cell. We were with other Jews and Communists who opposed the regime. The conditions there were unspeakable — crowded, without food or minimal living conditions. Every so often, the guards came and took a few prisoners out. We knew that whoever left didn’t return — he was shot to death right away. Anyone who left took out the food he had hidden for himself and distributed it to the rest, knowing he wouldn’t need it anymore.

Then a few days later they took us out also, up to the second floor, where a Nazi commander sat. Beside him was a vicious dog, and there was a translator in the room as well. He was one of our neighbors, a German national who lived in Kiev. He recognized us right away.

“These are my neighbors,” he told the commander. “I know their father. They are Ukrainians. They are not Jews and they are here by mistake. You can release them.”

The commander took out a sheet of paper and wrote down our names, and next to it, that we were Ukrainian. He signed the bottom of the page and released us. We returned to the house. It was already the beginning of the winter and Kiev was freezing cold. There was no heat at home, or food. We didn’t know what to do. But the Ukrainian neighbor in our shared apartment — a righteous woman named Sophia Kondratieva who lived with her daughter — knew we were Jews and had heard what had happened to our mother and siblings. She came into our section of the house and told us that from now on we were her children. She took us in and, to her great credit, cared for us like she did for her own children. She warned her daughter to tell anyone who asked that these were her brothers.

A few days later, the police again came to the building. They said they heard we were Jewish. We showed them the paper from the police commander, but it didn’t help. Then Sophia began to scream at them that we were her children, and why were they harassing two helpless Ukrainian children? She ordered them to leave, and her daughter also began to cry, sobbing that we were her brothers. This woman and her daughter saved our lives. Years later, they received the Righteous Among the Nations award from the State of Israel.

The war was at its peak and there was widespread hunger in Kiev. Grisha and I decided to sneak into the food distribution area where each citizen was given a small bread ration. It worked for a few days and we were able to bring a bit more bread to the house. But then, one evening, the Nazi gendarmes caught us stealing. My brother Grisha was able to flee, but they caught me and took me to the children’s hospital. Those beasts had transformed the place to an experiment center using humans. They did all kinds of frightening experiments on children as a punishment for the theft. They took me out to the frozen snow, in minus-15-degree weather, and stood me there for almost an hour without trousers until my legs froze completely. Then they dragged me inside, lay me on a bed and tried to heal my legs. I still have scars from those “experiments,” but I’ll spare you the details of the rest of the “treatments” I endured in that Gehinnom. I was there for half a year, a six-year-old child all alone in the world. In the end, I returned to the house, and miraculously, was able to walk again. My brother had returned, and our neighbor cared for us until the end of the war.

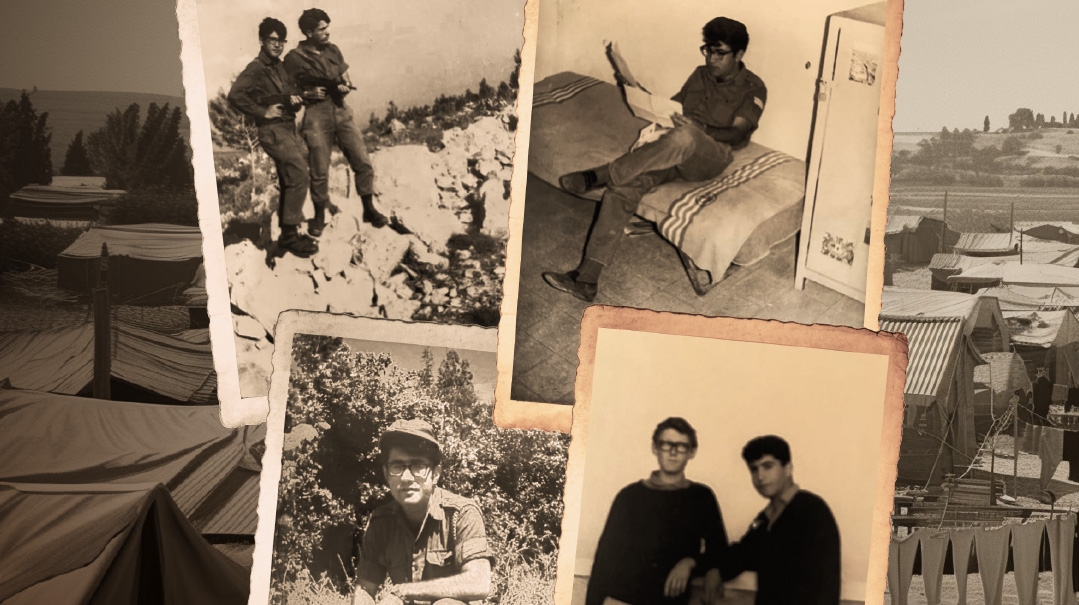

After the war, I became a loyal Soviet citizen. I was even a decorated officer in the Red Army. But the wartime trauma, plus many other painful encounters I suffered under the Soviet regime, led me to one conclusion: Never mention my Jewish identity. I never even told my children.

In 2000, following the rise of anti-Semitic incidents in Ukraine and, feeling a deepening desire to reconnect with his people, Michael and his wife made aliyah. In Israel, he finally found the courage to break his silence and felt safe enough to reveal his past.

But Michael is a victim of exile, a kosher Jew from a rabbinic family who for so many years knew nothing about Torah and mitzvos, yet whose mother and siblings unwittingly perished al kiddush Hashem. With the 80th anniversary of the Babi Yar massacre earlier this year, Michael has been interviewed by assorted media outlets, but after we speak, I sense there’s more he wants to tell me than the story he’s repeated many times already in Russian, the one language he speaks: “I’m 85 years old,” he says. “Is it too late to start learning something about Yiddishkeit?”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 906)

Oops! We could not locate your form.