Song of Hope

She was born much too soon and much too sick. Would my daughter survive?

Still in shanah rishonah, struck with a sudden severe infection, Rivka Ritvo was stunned when she learned that she was in labor — and that her baby would be born much too soon and much too sick. The doctors’ prognoses were grim, but baby Ashira defied all expectations

Rivka zipped the suitcase shut and looked around the guest room. Bags, check; tallis bag, check; garment bag and sheitel box, check, check. Their trip back to visit family in England had been a dream come true. She and Mendy were still in shanah rishonah, and Succos had been the perfect opportunity for a little vacation — and the perfect opportunity to bond with the siblings-in-law she barely knew and get pampered. It had been hard, starting out their married life in Eretz Yisrael, so far from all she knew and everything familiar — and then came the nausea.

Rivka shuddered, remembering. Those months of sickness had been so hard but baruch Hashem, they were behind her now, and all for good reason. Their siblings had been so excited to learn the news — she was still barely showing, but her brand-new maternity clothing had given it away. Now it was time to go home — but first, one last outing to cap off a picture-perfect vacation. The entire family enjoyed one last big family dinner in a local restaurant, and then it was time for Rivka and Mendy to head back to the airport for the long flight back to Eretz Yisrael.

“It was extremely hot when we arrived in Tel Aviv, and I felt woozy and overheated,” Rivka remembers. “Mendy was convinced I’d gotten dehydrated, and he kept passing me drinks, but my stomach was really hurting me.”

As soon as they got back to their small apartment, Rivka called her uncle, a doctor, and described her symptoms, which he found very worrisome.

“Straight to the hospital,” he said grimly.

Mendy was taken aback. “I’m just going to daven Shacharis first—”

“No you’re not,” her uncle said. “Go!”

Confused and worried, the young couple rushed to Bikur Cholim hospital.

In the emergency room, a nurse took her vitals — then went into panic mode. “Your fever is sky-high! What’s going on? And you say you’ve been having cramps? Are you sure they’re not contractions?”

A midwife examined her and made the grim pronouncement that Rivka was in labor — at just 27 weeks. Thirteen weeks too early. “Why didn’t you come in earlier?” the woman asked as she bustled around Rivka’s bed, a worried expression on her face.

“I… I didn’t realize I was in labor,” Rivka said weakly. “I just thought it was a really bad stomachache, because I was so dehydrated.”

“I wish you’d come in earlier,” the midwife muttered again, half to herself. “We could have stopped the labor.” She nodded at an orderly who had suddenly materialized, and before Rivka could understand what was happening, she found herself being wheeled down a long hallway to a delivery room.

In the delivery room, the bareheaded obstetrician on call looked at her, and sighed. “Pray for a miracle,” he told her. “Your baby’s chances of survival are very poor, given your condition.”

Terrified, she grabbed the phone and dialed her mother — who hadn’t known anything about what was going on. “I’m about to have a baby,” she sobbed. “The doctor says the baby probably won’t make it. And I didn’t even take labor classes! I don’t know how to breathe!”

Rivka’s mother was terrified, but too far away to help. She called Rivka’s sister-in-law, Dassy, who lived nearby. Dassy arrived and kept Rivka calm throughout the delivery.

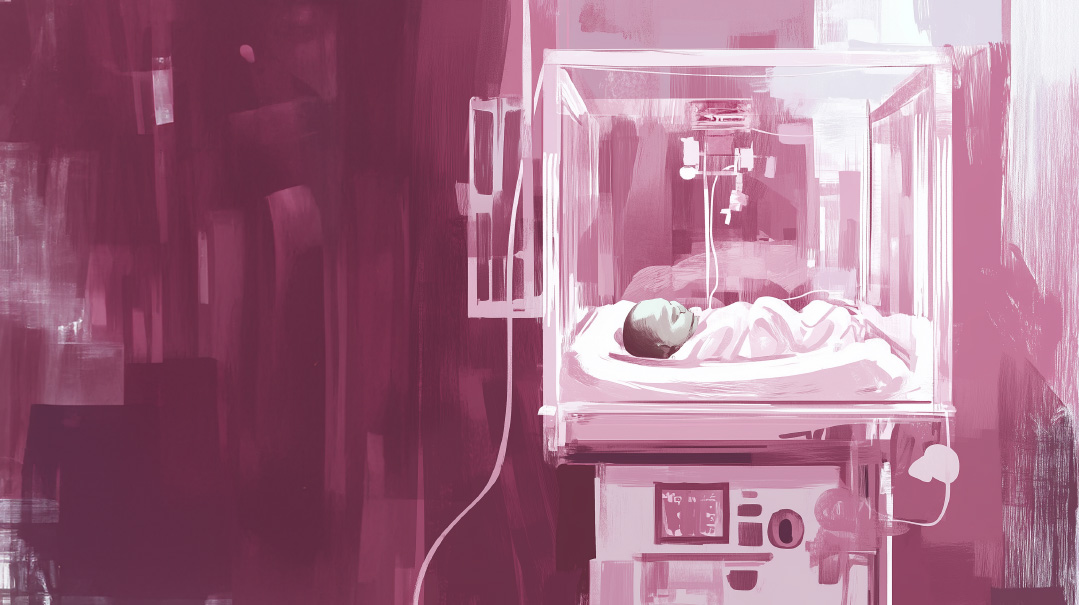

After several hours, Rivka gave birth. Instead of the expected cries of, “Mazel tov!” mingled with the sweet sound of a newborn’s cries, there was silence. “It’s a girl,” one nurse informed her soberly. “She weighs just one kilo (2.2 pounds).” The staff worked with quiet efficiency — clearing out the baby’s miniscule airways, attaching her to oxygen, and whisking her off to the NICU.

When the action died down, the room felt even emptier. Rivka looked around frantically.

“Where is she? How is she? Is she still alive?”

No one answered.

Finally, one nurse spoke. “You need to prepare yourself,” the nurse told Rivka, not unkindly. “There’s a good chance she won’t make it through the night. You have to understand, you have a very serious infection. Your baby is very premature, and very sick.”

After the nurse left the room, the midwife leaned over Rivka’s bed and whispered to her, “It’s a good thing she’s a girl. Girls are fighters.”

But Rivka couldn’t follow her fighter to the NICU; she was too sick herself. When the results of her bloodwork and cultures were in, they learned that Rivka had listeria, a rare infection she must have contracted somewhere amid the travel and eating out. The illness is especially dangerous for the elderly or women who are expecting, and it can lead to stillbirth. An estimated 1,600 people get listeriosis each year, and about 260 die, mostly the elderly and pregnant women.

The sickness left Rivka completely drained, feverish, and weak. She lay in bed with powerful antibiotics being pumped through her worn-out body, sinking under a wave of fear and despair, too weak to move. And then her brother walked into her hospital room, his eyes full of compassion and worry. “I wasn’t sure if I should come to visit you,” he admitted. “Maybe it would just be better for me to go to the Kosel to daven for you and the baby.”

“No, I need you!” Rivka told him. “Go find out if the baby is still alive!” she demanded. Together with a very frightened Mendy, Rivka’s brother headed into the NICU to find out the status of their tiny little daughter.

She was alive, but just barely — a fragile, frail being attached to tubes and poles.

Her husband snapped a photo and brought it back to Rivka, but try as she might, she could barely see her baby’s features amid all of the machinery keeping her baby alive.

Mendy went to shul. When he came back, he told his shocked wife that he had named the baby Ashira Rut. “I wanted to make you happy, so I named her Ashira. I know you love the name,” he told her. He’d added on the name Rut, after his mother.

BY the next morning, Rivka’s mother had arrived — she’d dropped everything to get on the first flight to Israel. She helped Rivka into a wheelchair, adjusted her IVs, and wheeled her off to meet her daughter for the first time.

“It was scary,” Rivka admits. “I wasn’t sure if the first time I met my daughter would be my last.”

But baby Ashira made it 24 hours — and then another day, and then another. When she was four days old, the NICU pediatrician told Rivka that her baby needed mother’s milk. But her premature delivery, coupled with her infection and a complete lack of trying to nurse for a few days, meant that Rivka had no milk. Rivka begged other mothers in the hospital to donate pumped milk, and the women gladly shared the life-feeding sustenance with the tiny infant.

The next two weeks went by in a blur. Rivka was still hospitalized, recuperating from the listeria. The doctors’ updates remained dark; baby Ashira’s chances of survival were slim, they kept telling her.

Ashira was attached to oxygen in the incubator; she’d been born too quickly to receive the Synagis injection most preemies receive to strengthen their lungs. Her muscles were too weak to suck, so she received all nutrition via a nasogastric tube. She had machines connected to her liver and her heart. Nothing was developed. Nothing worked on its own.

For the first weeks of her life, baby Ashira was so weak and ill that the merest physical touch could kill her. Rivka watched the other parents put their hands through the little portals on the side of the incubators. Even that small interaction with her baby was denied her. Eventually, they were encouraged to “kangaroo” the baby, once she was strong enough; Rivka was able to do skin to skin with her baby at long last.

“Our daily activity was checking the ‘weight book,’” Rivka says wryly. “Did she gain weight today or lose weight? That was our main concern. We knew if she passed the two-kilo mark, she’d be in better condition. Then we’d check the oxygen levels she was receiving.”

The medical details were all a blur for Rivka — a new mother still in shanah rishonah, recovering from a premature delivery and a serious infection, and all in a foreign language.

“I know she had issues with her heart and cysts on her brain and liver, but I tried not to ask too many questions. I preferred not to know too much,” Rivka said. “Maybe my denial was wrong, but hey, it worked.”

A hospital physician who examined Rivka told her that she was lucky she delivered when she did; had her baby remained inside, the listeria infection would have killed her. Rivka’s mind immediately flashed back to her time in the ER, when the staff had kept lamenting that she hadn’t come in earlier, when they could have stopped the labor. If they’d succeeded in stopping the labor, Ashira would not have been born alive.

Even as their daughter’s life hung in the balance, Rivka and Mendy had to contend with the mundanities and challenges of day-to-day life.

It didn’t help that many of the people who heard she’d given both asked her if she was joking. “I had barely been showing and was married for six months!” Rivka says. “Of course no one believed it….”

Their landlord didn’t think it was as funny, and he grimly informed Mendy that the apartment was not equipped for a baby and they were welcome to find a new home.

“My husband ran around from apartment to apartment, trying to find us a place to live, while our baby fought for her life in the NICU,” Rivka says.

And amid all of the craziness, they had to fight for insurance coverage. “We could only get Ashira on insurance if she had a visa, and for that, we needed a photo of her on a plain white background. We literally had to detach her from all the machines, snap a photo, and then reattach her as quickly as possible,” Rivka remembers.

When Ashira was a few weeks old, Rivka’s father flew in to help the young couple and meet his new granddaughter. Rivka accompanied him to the hospital — where they were stopped in their tracks by a large sign outside the entrance proclaiming that Kohanim could not enter the building. Since Bikur Cholim was a maternity hospital, Rivka realized that this must mean one of the babies had died. Her father, a Kohein, stayed outside and said Tehillim; trembling, Rivka raced inside to the NICU. The staff didn’t let her in.

“Please,” she begged them, tears streaming down her cheeks. “Just tell me who died! Was it Ashira?”

“Baruch Hashem, it wasn’t Ashira,” Rivka remembers, “But we lived with such uncertainty. We saw other babies in her NICU, in the incubators right next to her, who didn’t make it — but Ashira kept fighting. The Malach HaMaves was right there and he jumped over her.

“We decided we’d ignore the doctors’ prognosis,” Rivka says. “Ashira became our motto. We would praise Hashem for her very life.”

Somehow — improbably, miraculously — Ashira’s condition began to improve. It was a process — one step forward, two steps back. The NICU staff was able to lower Ashira’s oxygen levels, only to need to intubate her again after a setback.

Finally, just eight weeks after Ashira was born, she reached the milestones they’d all been davening for: She weighed two kilo (4.4 pounds) and could breathe on her own. The NICU staff pronounced her ready for discharge. Finally, Ashira was going home.

“I was so proud to finally push her in her stroller in the street,” Rivka remembers. “She was a perfect-looking, adorable tiny dolly.”

Caring for Ashira was a full-time job. Rivka needed to wake her up every two hours to feed her; Ashira only ate a little bit at a time, and she was still small and weak enough that she did not feel hunger. The hospital told Rivka that she needed to weigh her every other day to ensure that she was gaining weight. “The local Tipat Chalav clinic was a schlep, so I’d weigh her downstairs, in the little fruit and vegetable shop, on their produce scale. The shopkeepers thought it was hysterical.” Rivka laughs.

Ashira’s immune system was still weak, and Rivka needed to avoid crowded places or public transportation. But still, Ashira got sick often. When she did, Rivka would call her pediatrician, who would meet her in the clinic’s parking lot to examine Ashira; the office had too many germs inside for her to bring Ashira in.

“It was both exciting and exhausting having her at home,” Rivka says. “I didn’t have time to think about it. I was in survival mode. Raising a preemie is so hard.

“Hashem has a perfect system in place,” Rivka marvels. “Nothing compares to a baby growing for nine months, inside of its mother. Not all the machines in the world.”

But one by one, each of the complications disappeared. Miracle after miracle, Rivka’s tiny baby defied all odds. She had surgeries scheduled for her heart; they were canceled. Cysts on her liver and heart seemed to disappear miraculously; Rivka would schlep to the doctor to check on them, and there’d be nothing there.

Ashira is now 14 years old, a wonderfully warm, happy girl who loves babies and helping out. She went for years of physiotherapy and occupational therapy. She’s in a smaller class, where she can receive more individualized attention, in a large mainstream Bais Yaakov school.

“She may be a bit different from her peers academically and socially, but she’s physically healthy and happy and that’s what matters,” Rivka says. “Ashira is really the perfect name for her. We wanted to sing to Hashem for all the good He did and does for us.”

When Rivka told Ashira a magazine was interested in hearing the story of her birth, Ashira beamed.

Then she said, “But tell them it’s a happy story, okay? It shouldn’t be sad. Because I’m amazing.”

Message to a NICU Mom

Shevi Rosner

Mazel tov on your baby! I know you’re wondering how your baby ended up in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and how you ended up a NICU mom.

The NICU can be a scary place. Your stress and hormone levels are high, and the fear is real. The layout is different from the postpartum unit with the cute well-baby nursery nearby. The NICU appears more medical, serious, and intense. As a NICU nurse with over 15 years experience, here are my tips for getting through your NICU journey.

Get to know your baby’s nurse. The nurse is always at the baby’s bedside, does all the hands-on care for your baby, and serves as your baby’s eyes and ears. The nurse will usually give you general updates, but for specific information about bloodwork or test results, you should inquire of the provider.

Typically you will be encouraged by the nurse to be involved in the baby’s care from birth onward. When babies are born extremely prematurely (as early as 22 weeks!), hands-on care may be minimal, but with time, opportunities for parental involvement increase. If your baby is in the NICU for a lengthy stay, you may become very close with your baby’s nurses and begin to prefer or favor some nurses over others. See if your NICU allows for consistent nursing. This provides optimal continuity of care, allowing your baby’s nurses to become experts on his or her normal status, knowing quickly when things seem abnormal or different from baseline.

Ups and downs are part and parcel of the NICU journey. A baby may take four steps forward and two steps backward. This is common, but yes, it is stressful! It’s critical that you stay informed of changes, progress, and setbacks. You can track this by taking some quick notes every day or so. Write down questions in a notebook as you think of them. If you can, be present during daily rounds when the larger group of team members discuss the history of your baby’s stay, current issues and concerns, as well as the plan of care for the shift and coming days. You can learn a lot about your baby during these informative discussions.

Aside from being present, calling for updates, and advocating, you can be involved in your baby’s care by pumping. While alternate options are available for feeding donor milk (there is a kosher donor milk bank in New York) and formula, your milk is the best option for your baby.

Much of the NICU journey requires patience and time. Patience for the baby to grow, to thrive, to wean off medications and medical support, and to work toward discharge. The medical team can support and encourage the baby’s progress, but the baby’s readiness cannot be forced. It just takes time.

As you wait for your baby to grow and thrive, you can receive support from other NICU parents. Just remember that no two cases are exactly alike; one baby’s journey may be quite different from yours even if the diagnosis or gestational age is the same. WeeCare is a frum organization for parents of preemies, founded by former NICU parents. They can connect you with others in your situation, and they offer a range of services. Other organizations, including Chai Lifeline and Highway of Hope, can help you navigate your baby’s diagnosis and journey. You can also stay involved and in a positive mindset by making a scrapbook to highlight your baby’s milestones. Keep that little hat and diaper — you won’t believe how fast your baby grows!

Some of the goals of the NICU stay are for your baby to grow, be medically stable, maintain their own temperature, and consistently gain weight. Some of these issues can hold up discharge, but you don’t want your baby to go home before it is determined safe and appropriate. An early discharge may mean a visit to the emergency room in the coming days or unnecessary concerns at the pediatrician’s office.

Most NICUs are overflowing with babies; they have no need to hold on to your baby for more time than necessary. We’re on your side and want your baby home with you as soon as possible. Discharges are big celebrations, and many nurses will cry emotionally when a long-awaited discharge happens. Sending a follow-up card or photo in the months after discharge is very encouraging for the NICU staff. We celebrate and get excited for you and your baby’s progress, and we get encouragement and chizuk to continue helping other babies.

Shevi Rosner MSN, RN, has been working as a nurse in New York Presbyterian Children’s Hospital since 2007 and is currently pursuing her doctorate in nursing. She is the former president of the Orthodox Jewish Nurses Association and an active volunteer.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 907)

Oops! We could not locate your form.