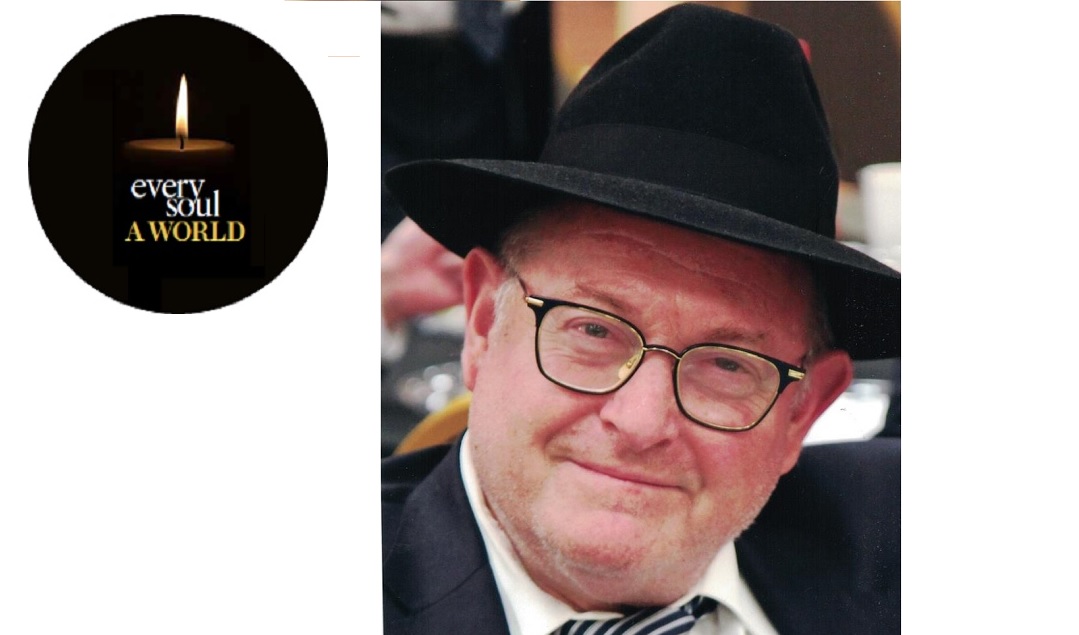

Rav Yehuda Jacobs

His approach was the furthest thing from preaching. Instead, you felt his desire to live life as a better human being. In Tribute to Rav Yehuda Jacobs

So Human, So Great

I

was 13 years old and living in Scranton, Pennsylvania when my mother remarried a special widower: the venerated mashgiach and unmatched baal eitzah of BMG, Rav Yehuda Jacobs. People say that when you get close to greatness you start to see the flaws. But I experienced the opposite.

I won’t pretend to understand or try to define the giant who became a father to me; I can only attempt to describe what I saw from my unique vantage point of a very great man.

Rabbi Jacobs – or as we called him, Tatty -- was totally congruent. He saw himself as the most ordinary of people; the only difference being that he didn’t demand the ordinary amount of respect.

A lifelong talmid of Rav Aharon Kotler, his hallmark was commitment. He had an incredible sense of achrayus to Hashem, to Klal Yisrael, to his wife and children. He was always deeply thinking, always pondering the truths of life, aiming to achieve a deeper appreciation of everything important. For example, I once asked him what he was thinking about. “Yehei shmei rabbah,” he told me. “When we say ‘rabbah,’ what picture comes to mind? Does it in any way reflect the greatness of Hashem’s name? How great is that name?”

Tatty achieved opposite extremes with seeming ease. On one hand he was self-effacing, always putting his needs last. He would move methodically from effort to effort doing what he called “the next right thing…” On the other hand, he was one of the firm and powerful leaders of the world’s largest yeshivah.

On one hand, he carried the weight of the world on his shoulders. He felt the pain of the people he counseled all day, every day. His own life was replete with yissurim, both emotional and physical. On the other hand, he was always in a great mood. When I picture him, I think of him humming to himself, exuding serenity and contentment.

On one hand, he was the ultimate baal avoda and baal mussar, a talmid of Reb Yisroel Salanter’s mehalech and Reb Nosson Wachtfogel. On the other hand, he never seemed to be acting from a place of pressure or guilt, and his approach was the furthest thing from preaching. Instead, you felt his desire to live life as a better human being.

As a teenager in yeshivah, I remember asking him for his take on wearing a black hat. His simple answer stays with me still. To him, it wasn’t just a badge of Torah affiliation, but about his self-esteem as a human being. “When I was a kid,” he told me, “every man wore a hat. A man’s hat is a simple sign of self-respect. President Kennedy changed the style at his inauguration by appearing without a hat. But I don’t feel like letting Kennedy affect my choice of style or self-respect.”

Another seeming paradox: Rabbi Jacobs seemed most comfortable meeting and conferring with gedolei Torah v’avoda and the talmidei chachomim that he held in the highest esteem. But he seemed equally comfortable caring for Lakewood’s estranged “kids of the lake,” who would visit him on Shabbos afternoon, or spending time with his grandchildren.

The theme that remains with me most about my step-father was his deep appreciation of the human being. He loved humanity and managed to discern the inherent greatness within every person he met. I believe that his greatest aspiration was to be a true human being.

Now that he is in the Olam Ha’Emes, I wonder how a human can be so great. And I wonder, too, I wonder how greatness can be so human.

— Rabbi Ephraim Stauber

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 809)

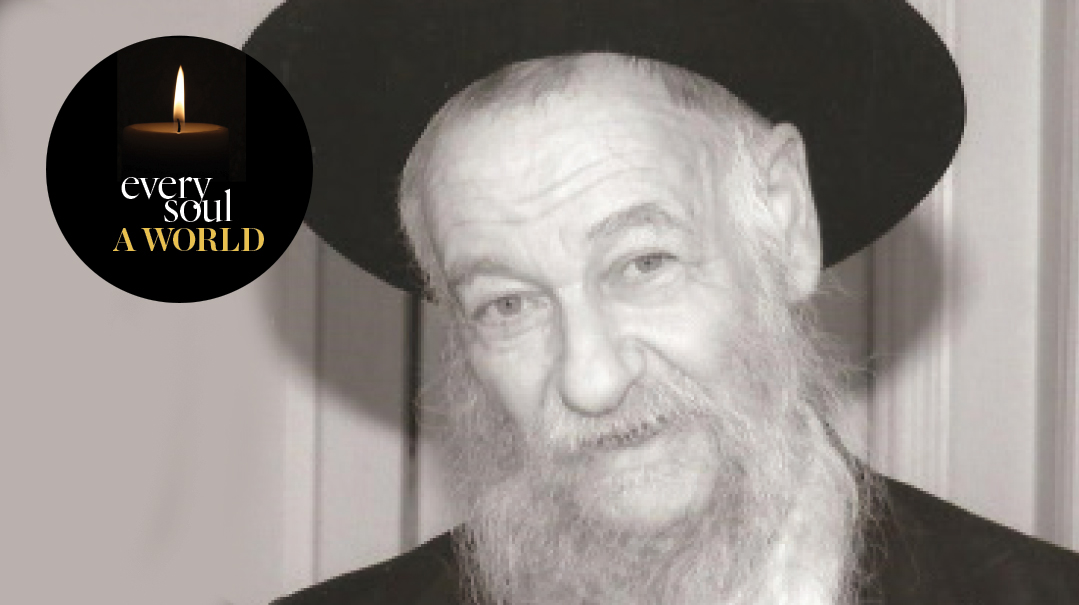

THE BEST ADVICE

A

long with the pain and darkness of these days, there is also the confusion and lack of clarity: What does it all mean? How are we to respond? Where can we find the tools to cope, to keep the atmosphere in our homes and hearts calm?

And then the man who so many turned to for the answers -- the voice of reason and truth and seichel hayashar, Rav Yehuda Jacobs, mashgiach of Beth Medrash Govoha of Lakewood -- was himself taken.

On Monday morning, the 3rd of Iyar, the dreaded virus claimed him as well. It wasn’t only his family and talmidim that were plunged into mourning, it was a great anonymous network, a mass of people who’d come over the years seeking advice and direction, homes he’d helped build and families he’d kept together, known to no one but him, them, and the Ribbono Shel Olam.

The Lakewood roshei yeshivah were maspid Rav Yehuda by quoting the Mishnah in Avos, that one who learns Torah lishmah merits that “venehenin mimemu eitzah veshoshia,” people benefit from his advice and assistance.

The fact that Rav Yehuda was the baal eitzah of Lakewood -- the yeshivah, the community, and the olam haTorah it spawned -- was itself a product of his Torah learning. He arrived in Rav Aharon Kotler’s Lakewood in the late 1950s, a bochur determined to attach himself to the Rosh Yeshivah. And attach himself he did, becoming one of the close talmidim, respected as a lamdan and masmid in a chaburah filled with lions.

In time, he would publically review Rav Aharon’s shiurim with the other talmidim, and by the time Rav Aharon was niftar, Rav Yehuda was a fixture in the beis medrash. The new rosh yeshivah, Rav Schneur, wanted him to remain as part of the administration and appointed him mashgiach.

In Lakewood, Rav Yehuda Jacobs was the mesorah, the link back to that small chaburah that had founded the yeshivah, available not just to clarify the substance of the Rosh Yeshivah’s Torah, but the spirit.

One of today’s most prominent roshei yeshivah recalls arriving in Beth Medrash Govoha as a young kollel member and having the zechus to be set up as a chavrusa with Rav Yehuda. It was a special privilege to learn with this senior talmid, and the new study partners sat down to learn on the first day of the zeman. It quickly became clear to the avreich that his path in learning was different than that of the mashgiach, and that he wouldn’t do well in the chavrushaft. He tried it the next day, and at the end of seder, he felt that he had no choice -- uncomfortable as it was, he broke up with the respected mashgiach, explaining that he felt he needed a different type of chavrusa. Rav Yehuda gently accepted it and wished him well, and the next day, they both found other learning partners.

The yungerman was still feeling uncomfortable about it, but in the middle of first seder, Rav Yehuda Jacobs approached where he was sitting with his new chavrusa. “I’m sorry to disturb, but you said a pshat in the Ritva yesterday. Can you just share it with me again? It was so geshmak,” Reb Yehuda said.

The yungerman shared the approach again, and Rav Yehuda thanked him and walked away, leaving his former chavrusa-of-a-day with an overwhelming sense of awe: awe at the way the mashgiach had managed to put him at ease -- reassuring him that everything was okay between them and there were no hard feelings -- through the Torah itself, the Toras chesed that guided him.

“I’ll Help You”

Rav Yehuda Jacobs was blessed with natural perceptiveness and wisdom, a keen insight into people. As a three-year-old boy, arriving with his parents from Germany, he noticed the worry on his mother’s face as they embarked from the ship onto US soil, into a new world. “Don’t worry, Mammah,” little Yehuda said, “I will help you.”

It was a statement that would mark his destiny – always taking notice of the needs of others and having the ability to encourage them.

In the yeshivah that would become the station of bochurim looking for their life-mates, his listening ear and wise advice was the final step in making shidduchim happen. After the engagement, when there was confusion or anxiety, it was back to the mashgiach’s house for another session. How many chassanim and kallahs came to him with cases of cold feet? He knew not just to validate, listen and guide, but also to give them pure Torah hashkafah, his advice layered with the very kedushah of Torah itself, the ultimate truth.

The final ingredient was the achrayus, the sense of responsibility. He well understood insecurities and fears, and was willing to stand behind the advice he gave. It was this last factor that built homes, that kept children in school, that empowered people to accept positions.

In this world, the effects of that generosity of spirit could never be measured. It’s only in the world of truth that the full effect of the mashgiach, Rav Yehuda Jacobs, and what he accomplished will be rewarded.

— Yisroel Besser

Oops! We could not locate your form.