Silent No More: The Choral Synagogue of Moscow

| June 5, 2019S

ome of my earliest memories are from the Moscow Choral Synagogue, the grand building located on Moscow’s Arkhipova Street, minutes away from the Kremlin.

My father, Rav Pinchas Goldschmidt, founded the first beis din in Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union. My mother, Rebbetzin Dara Goldschmidt, founded one of the first Jewish day schools in Moscow. What did I do? I was the first child to make noise in a shul after the fall of Communism. (My older brother Dovi was well-behaved, while I was the troublemaker.) We were the only kids to drink from the Kiddush cup on Friday nights.

Chaos and Community

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz started the first yeshivah, which was in Moscow’s Kuntsevo District. My parents moved into a yeshivah dormitory with two little children — I was two years old — to teach Torah. The Jewish community infrastructure had to be built from the ground up. Kashrus, batei din, shuls, yeshivos, schools, a chevra kaddisha — everything was in its beginning stages.

At the time, in 1990, over a million Jews lived in Moscow. Most lived with their suitcases half-packed, waiting to get their papers to emigrate to Israel, Canada, the US, and even Germany. Many others chose to remain in post-Soviet Moscow, either because of an older parent or because they didn’t want to start from scratch in a foreign land. But anarchy ruled during this time, when Russian democracy was in its infancy and the whole system was in transition. The city seemed to be always under construction. Drunks lay in the corners of metro stations. Wild dogs ran loose throughout the streets in the early mornings.

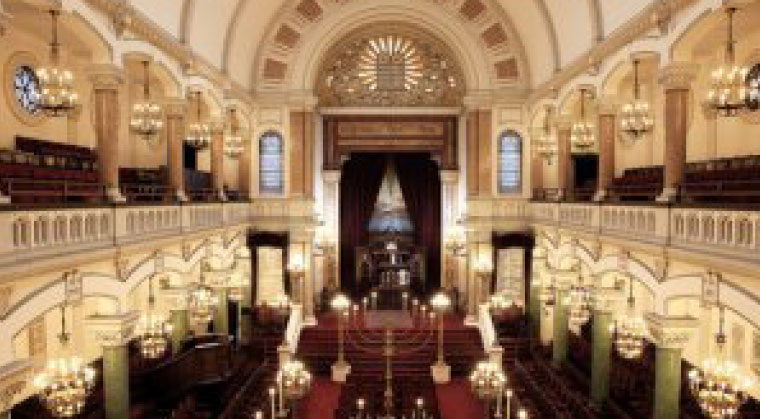

When my father became the Chief Rabbi of Moscow in 1993, I would walk with him to shul through snow and ice. Even as a young child, when I passed through the towering white columns of the Choral Synagogue, then entered through the huge wooden doors — which I couldn’t open without the assistance of an adult — I knew it was a building of great historical significance. After all, it was not just a synagogue. It was the only overt symbol of Judaism that had withstood 70 years of Communism. From Lenin to Stalin to Gorbachev, the synagogue’s doors remained open — mostly for show, by government decree — but open nevertheless.

Something was always happening in that building. I remember packages and packages of kosher food sent by the Joint Distribution Committee: mainly gefilte fish, grape juice, and matzos. (The community members used to joke that the Joint would only send matzah because they could stamp their logo on the box.) I remember a long line of people waiting for kimcha d’Pischa. I remember groups of Jews who would come for Simchas Torah, not walking inside, but instead playing an accordion (garmoshka) and dancing to songs like “Hava Nagilah” and “Oseh Shalom.”

Outside the sanctuary, the Evreiskaya Gazeta, the Jewish Gazette, was available for free. That’s the first newspaper I remember reading.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

During the first few years, there was always suspicion between Jews — everyone suspected everyone else of collaborating with the KGB, the Soviet secret police.

When my father first came as the mara d’asra, a man walked over to him and pointed out someone in the shul, saying, “Young rabbi, be careful. That man is part of the KGB!”

As soon as he left, the other man came running to my father and said, “Rabbi, the man you just spoke to is a KGB informant!”

I asked my father whom he believed, and he said, “I believed them both.” Even long after the KGB stopped tracking every person who walked into shul, its long shadow remained.

Other regulars were the Jewish beggars, who waited at the steps of the synagogue, asking for “pomosh” (help). They often targeted foreigners. Though I had no money, they always tried to strike up a conversation, telling me of their tzuris.

As for the regular daveners, they were mostly elderly people. Some went to cheder before the 1917 revolution. Many of them wore their military medals as badges of honor. They had fought the Nazis in World War II, and they spoke a Russian Yiddish. They were also the only people in Russia who knew how to daven. In a city that had at one point over a million Jews, only a select few knew how to hold a siddur.

One of them was Alexander Yakovlevich, who was a sort of gabbai on weekdays. He wore the old litvish rabbonishe yarmulke on top of his graying red hair, like the ones I later saw Rav Shach and Rav Michel Yehuda Lefkowitz wear when I learned in the Ponevezh Yeshivah.

Another was Ilya Yosovich, a man of great bearing who wore elegant suits and who served as the gabbai on Shabbos. He was one of the few who knew the value of shlishi or Maftir Yonah. A polkovnik, or colonel, in the Red Army, he had more medals than the others. His favorite tefillah was V’chol Maaminim. He said he would go from one shul to another to see who had the nicest tune. And who better than a Jewish colonel in the Red Army could testify to faith in our Creator?

Upstairs, you’d meet Nona Zacharovna, a warm-hearted, chatty old lady who helped give out the siddurim and Chumashim in the women’s gallery. She would give brachos for half an hour straight without repeating a word, probably outdoing the most skilled mekubalim of Israel. You knew that if she started giving you a brachah, you might miss shkiah.

One of the elders, Binyumin, conducted business when it was illegal to have any private enterprise. He would secretly connect a buyer and seller by bringing them to shul, place a tallis over both of them, negotiate the sale of a dacha (a summer home on the outskirts of the city) and take his cut. The KGB spies had no clue as to what was happening. When business became legal, Binyumin started a yarmulke rental company, where he would approach a tourist walking into shul on Shabbos and offer to rent out a yarmulke for ten dollars for the hour. My father tried to persuade him not to do this, but he continued. He finally moved to Australia to join his children. But he soon returned to Moscow. He said he couldn’t do business in Australia because there they all came to shul with yarmulkes.

These old Jews were my closest childhood friends, the people I would schmooze with, listening to their legends, answering their questions. I would listen to them tell stories about the battles they fought, all of them carrying black and white photographs of themselves as young officers. They would speak of the difficulty of teaching Yiddishkeit in Soviet Russia — how children never came to shul in those years.

Dead Fish Not Allowed

Conversations with different people in shul kept me busy during the long tefillos, which often included a cantor and choir. My mother would sit in the first row of the balcony, and when I talked too much, she shushed me from above. That was my personal understanding of what a “bas kol” is. Another time, she told me that when I walk down the aisle and a davener extends his hand, I shouldn’t give him a “dead fish,” but an enthusiastic handshake. I try to follow her guidance to this day, as a rav in a shul in New York.

On the Yamim Tovim, the shul would be overflowing with thousands of people filling all the pews and aisles. Many held the siddur upside down; many stood silently and gaze ahead. There was a sense they wanted to connect but didn’t know how. Dovi and I were tasked with keeping track of the page numbers to allow people to follow along. We had three plastic bottles with numbers on them, and we had to turn the bottles to display the correct page number to the community.

On Yom Kippur, during Ne’ilah, my father would stand in front of the congregation and say, “Repeat after me: ‘Hashem, Hashem, Keil Rachum v’Chanun.’ ” You heard the silent Jews of Moscow roaring the Thirteen Middos of Divine Mercy at the end of the holiest day of the year. To this day, every year, I get goosebumps during Ne’ilah, remembering that Russian roar, that pure cry.

When I was 12 years old, I was sent to learn in yeshivah in Bnei Brak. I flew back for my bar mitzvah to lein in my childhood shul. I was born on Yom Kippur, so I had the chance to lein the words of Yeshayahu: “V’amar, solu, solu, panu darech.” I remember the serious faces in the crowd lighting up with smiles, looking at the little troublemaker being called for the first time to the Torah. That was the last Yom Kippur I had the privilege of davening in my shul, davening with my family.

Minyanim and Herring

The Moscow Choral Synagogue is a grand complex of many offices, organizations, and minyanim, all in one building.

One of the most fascinating stories concerning the building was the removal of the dome at the top of the synagogue. Legend says that the czar’s nephew, then the governor of Moscow, once passed by the shul while he was intoxicated, and he crossed himself, thinking it was a church. When his driver corrected him, saying it was a synagogue, the governor demanded that the dome be removed. A century later, the mayor of Moscow, Yuri Luzhkov, restored the dome to the building.

The daily minyan was held in the Cheder Sheini. There are stories of Rav Moshe Feinstein teaching Torah in the Cheder Sheini in 1934, while waiting to leave for New York, despite pressure from the Soviet regime. Later, many of the refuseniks used to gather there, including Yuli Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset in Israel.

There were three other robust minyanim. After the fall of Communism, Jews from all corners of the Soviet Union came to Moscow. Some came to settle, while for others it was merely a stop on the way to leaving Russia for good. We had a large Kavkazi community — Mountain Jews (also known as Gorskiye Evreyi) from the Caucusus Mountains. Some say they are descended from the tribe of Yissachar, and many of them had the family name Yissacharoff. They were mostly traders, businessmen who dove into the anarchic capitalism of the 1990s. Many of them were extremely successful.

Then you had the Bukharian Jews from Uzbekistan and the Georgian (Gruzini) Jews. Each community had its unique customs and nuschaos. The Georgian Jews tended to be the “frummest,” as the Communist regime was most lax in Tbilisi. Throughout the Soviet years, they had chachamim and 14 functioning synagogues. The men had bris milahs, and many tried to observe kashrus. Their community emerged from Jews exiled to Bavel after Churban Bayis Rishon. Their Moscow leader’s name was Chacham Yosef; he had a trimmed beard and was extremely respected.

I remember once witnessing on Erev Yom Kippur the Bukharian rabbi giving malkos to one of the mispallelim. The man had his shirt off and was leaning on a column, and the rabbi was whipping him with a leather belt. His back was turning red. I got nervous for the guy, until I heard him saying: “Rabbi, hit harder! Davai sil’neye!”

Kiddush was also an interesting experience. There would be more vodka than soft drinks, a lot of selyodka (herring), and the people would sing songs — mainly Yiddish classics like “Tumbalalaika” and “Lomir Alle” — with passionate nostalgia.

In the main sanctuary, there used to be a closed wooden box with a few seats. They say it was built for Golda Meir, who visited the synagogue as the ambassador to the Soviet Union of the newly created State of Israel. The Soviets didn’t want her to mingle with local Jews, so they had to build her a separate section in the shul, which was later used by other foreigners. When she came, it wasn’t publicized anywhere that she would appear in the shul, yet the silent Jews of Moscow spread it by word of mouth, one by one. When she arrived, 50,000 Jews had congregated, waiting to catch a glimpse of her. Meir later said it was one of the two most important moments of her life.

Silent No More

Today, the building is renovated, the street is renamed, and the beggars are mostly gone. The Golda box has been removed, along with the blessing for the USSR, and the bimah is placed in the middle rather than the front. Nona Zacharovna, Ilya Yosovich, Binyumin, Alexander Yakovlevich, and Chacham Yosef are all in a better world. The average age of the mispallelim is 40 and not 75, and they all know how to daven (although no one speaks Yiddish). During Friday night Kiddush, there is a line of many children waiting for a sip of Kiddush wine.

On a return trip, I stand there, in that grand sanctuary, and I remember that once, after making a lot of noise during davening, I was hushed by one of the mispallelim. I’ll never forget the reply of one of my elderly friends: “Don’t you dare shush the child! I waited for 70 years for children to once again make noise in shul.”

Those memories, those tefillos, said out of thirst for the word of G-d after years of repression, accompany me until this very day. And today, as a rav myself, whenever I hear children making noise in shul, I remember that old man who waited decades for that noise. And I smile.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 763)

Oops! We could not locate your form.