A Shul in the Congo

Rabbi Shlomo Bentolila, never gave up. Week after week he called every single person in the kehillah, exhorting them to come Shabbat morning. Soon his efforts began to pay off, and we had a regular minyan.

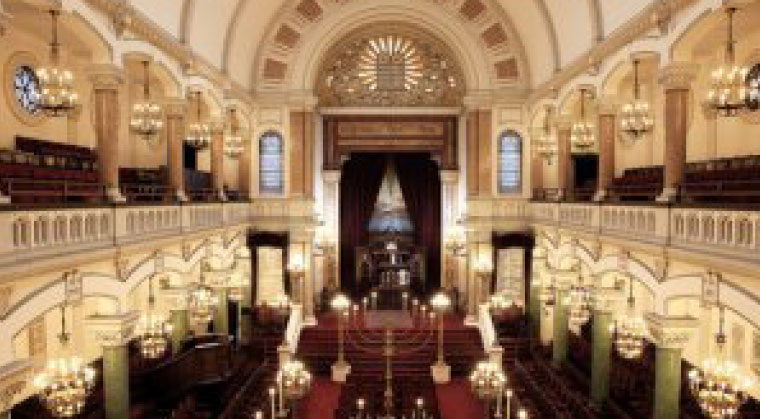

Iwas three months old when the Lubavitcher Rebbe sent my parents on shlichut to Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (called Zaire then, in 1991). Our Beit Chabad housed a mikveh in the basement; the shul, called Beit Yaakov, along with my father’s office and my mother’s Hebrew classroom, on the main floor; and on the top floor, our residence, which was open to all for meals on Shabbos or any day of the week.

My parents arrived to an established community of around 250 Jews who originated from Egypt, Turkey, and the Island of Rhodes in Greece. The lingua franca was French.

Friday nights in shul were quite special. I, the only little girl present, would put on my nicest clothes and go downstairs to hear the beautiful, rhythmic Moroccan melodies that were sung by the community.

Shabbat day was another story, at least in the beginning. Most in the community were secular and wanted to spend their day off in leisure. But my father, Rabbi Shlomo Bentolila, never gave up. Week after week he called every single person in the kehillah, exhorting them to come Shabbat morning. Soon his efforts began to pay off, and we had a regular minyan.

After tefillah, everyone would come upstairs for a traditional seudah. My mother, Rabbanit Miriam Bentolila, served two varieties of fish: her delicious Moroccan recipe, along with her homemade gefilte. A very diverse menu followed: Persian rice and French roast, Israeli salads and Mediterranean dishes. Everyone’s traditions were embraced, and everyone felt at home, sharing stories and singing their own traditional niggunim —Spanish Jewish songs, Sephardic songs, and Chabad niggunim.

The same held true for holidays: all the community’s children would come and sing songs and do fun activities with my mother, like making latkes and doughnuts for the Chanukah party. To this day I still sing a Spanish song we learned about Chanukah: “Una candelita, dos candelitas…” (One little candle, two little candles… until ocho, eight.)

I’ll never forget one Rosh Hashanah afternoon — we had just finished the seudah, when the shul security guard announced that a French man was at the door. My father went to greet him. He was a Jew, his name was Pierre, and he was very far from Yiddishkeit, but he knew it was nearly Yom Kippur and he decided to come by. We made Kiddush for him, and then my father brought him downstairs to the shul to hear shofar.

Pierre told my father that his parents had been terrified to reveal their Jewish identity, and only raised them to keep Yom Kippur, which they observed at home, without leaving the house. My father invited him to come the next day to shul.

During Krias HaTorah my father called Pierre up for an aliyah, and asked for his Jewish name. Pierre replied that he didn’t have one but that it was probably Even — a literal translation of his French name, which means “stone.” My father told him this was his chance to choose a Jewish name. After some thought, Pierre asked to be called Aharon.

At the seudah after davening, we wished him mazel tov on his first aliyah and on his new Jewish name. We asked him why he chose that name in particular. He responded that he had no idea why, but he liked the name. Later during the meal, he mentioned that his mother had told him of a family custom never to enter a cemetery.

My father then answered him that it meant he was probably a Kohein, explaining what a great privilege it was, and then pointed out to him, “You see? It was with Hashem’s guidance you chose the name Aharon, since you are his descendant.”

I also remember a man in our community, over 70 and so far from Yiddishkeit that he had never once fasted on Yom Kippur, who encountered major financial stress. He started coming to shul every day, laying tefillin and learning a bit with my father.

They eventually came to parshas Vayigash, recounting Yosef’s tearful reunion with Binyamin where they each cried on each other’s shoulders. Rashi explains there that Yosef cried over the Batei Hamikdash that would be destroyed in Binyamin’s future territory, whereas Binyamin cried over the Mishkan of Shiloh that would be destroyed in Yosef’s future territory.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe, in a sichah, asks why each of them didn’t simply cry for his own churban. He answers that one can’t cry for one’s own destruction —one must act to rebuild one’s own mikdash. But for another Jew, if you did all you could to help him avert destruction, and still he fell… for him you must cry.

I remember when my father learned this with that man — I passed by the shul and saw him crying so much. My father later explained to me why he was crying. I was deeply moved that even a Jew that far from Torah could be so touched by one of its teachings. That man never missed another day of shul, and fasted that Yom Kippur for the first time in his 70 years.

Growing up in an atmosphere like that, in the faraway Congo, imprinted on me like nothing else could that all Jews are precious, whatever our differences.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 724)

Oops! We could not locate your form.