Shabbos Sacrifice

Police violence was an embarrassing and uncomfortable chapter in Israel’s early history, but in the end, a hidden stash of transcripts shed light on a young bochur who would fight for justice at all costs

ne fall morning in 1956, the phone rang in the Chevron yeshivah office.O

“Can you call Chaim Rottenberg?” the caller asked. When he was told that the bochur was not in the yeshivah building right then, the voice on the other end asked to relay a message: “Tell him his cousin wants to meet him at Café Rimon.”

Chaim Rottenberg had been one of the handful of witnesses to a horrific incident at a Shabbos demonstration a month before, when he saw a Yid in his fifties pushed to the ground by police, pleading for his life before he fell unconscious. He couldn’t think of any cousin who would call his yeshivah to set up a meeting at a café.

He shared his suspicions with his friends, and they told him they’d handle it. A few minutes before the appointed meeting time, the bochurim stood outside the restaurant, as they saw a plainclothed man step out of a police car and into the café, take a seat at a table, and wait.

A few minutes later, one of the bochurim entered, sat down across from the detective, and said bluntly, “You’ve come to meet Rottenberg. What do you want from him?”

The detective was a bit taken aback.

“One of the commanders of the Jerusalem police department wants to meet him,” the detective said. “For his own good, he should meet with us before he gives any testimony.”

The bochurim realized that there were forces within the police ranks who would do everything possible to distort the testimony of the bochurim regarding what took place that Shabbos. And at that moment they decided that each one of them who had even the slightest shred of information would come to testify.

Nine years earlier, as the British Mandate in Palestine was coming to an end, there was a strong probability that the United Nations would approve a Jewish state. Still, Jewish Agency executive chairman David Ben Gurion was nervous. The UN was to send a fact-finding team to Eretz Yisrael to establish the nature of this future state, and Ben Gurion — anti-religious as he and his colleagues were — wanted to make sure he had the support of the Agudah leadership both in Palestine and around the world. He certainly didn’t want Agudah leaders telling the UN representatives that the Jewish Agency didn’t represent the demographic of Torah and traditional Jews in the Holy Land.

And so, in cooperation with Agudah leader Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Levin and Vaad Hayeshivos head Rabbi Zalman Sorotzkin, Ben Gurion drafted the famous “status quo” agreement, which met the Agudah’s basic requirements for their consent to the founding of a Jewish state: that marriage and divorce would be under rabbinic authority, kashrus would be observed in an official capacity, there would be autonomy in religious education, and Shabbos would be publicly observed as the official day of rest. (Ben Gurion wasn’t really bothered by this gesture of appeasement at the time — he didn’t believe the chareidi demographic would last more than a decade in the new, progressive state.)

But less than a decade later, in the summer of 1956, disturbing events in Jerusalem threatened to upend the status quo.

It began with a group of secular residents who organized transportation to the beaches of Tel Aviv on Shabbos. Hamekasher, a transportation company that later became part of Egged, ran these Shabbos excursions from the neighborhoods of Romema and the city entrance (near the corner of Mossad Harav Kook, opposite where the Chords Bridge is today). For the religious Jews of Jerusalem, it was a serious breach of the delicate agreement that hadn’t been crossed until now.

It became the summer of the Shabbos riots.

Jews began to gather from all over the city on Shabbos afternoons to protest. The demonstrations were initially organized by the vehemently anti-Zionist Neturei Karta, whose leader, Rabbi Amram Blau, was arrested Shabbos after Shabbos. After a few weeks, though, the demonstrations drew Jews from all the communities, among them students of the Chevron yeshivah (then located in the Geula neighborhood), as per the directive of rosh yeshivah Rav Yechezkel Sarna.

Although the protestors came unarmed and dressed in Shabbos clothes, the demonstrations were accompanied by extensive police violence and arrests; in addition, secular youths would turn up at the scene to instigate the demonstrators and empower police violence.

As the tension escalated, in the last week of Elul, a decision was made that all of Jerusalem’s Torah observant residents would go out to daven Shacharis and demonstrate together early Shabbos morning. This time, the kol korei wasn’t signed by the rabbanim of the Eida Hachareidis, but by Rav Tziv Pesach Frank, the av beis din of Jerusalem; Rav Dov Berish Weidenfeld, the Tchebiner Rav; Rav Zalman Sorotzkin; Mir rosh yeshivah Rav Eliezer Yehuah Finkel; and Porat Yosef rosh yeshivah Rav Ezra Attiyah.

This time, the protest had consensus backing. The gedolei Yisrael even asked the gabbaim of the shuls to close the doors between 7:00 and 8:30 in the morning in order to guarantee maximum attendance.

That Shabbos, the police waited with increased reinforcements near the shuk, which slowly filled with Jews. Participants came to daven in the courtyard of the Eitz Chaim yeshivah, after which they began to march to Romema.

The papers were calling it “Black Shabbos” even before Shabbos had begun. By midday Shabbos, however, it was clear that this foreboding name would stick forever to a Shabbos that became a bloody symbol of the tension that would stain relations between the chareidim and the police for years to come.

More than a thousand people stood on Jaffa Road at the time, but within an hour after Shacharis, a violent clash broke out between police and the chareidim. The police were assisted by dozens of hostile secular youths who had no problem lunging at the chareidim. At one point, police began throwing stones into the crowd, alongside the violent youth.

“Police were hitting left and right,” a clerk from the Welfare Ministry who was passing by testified to an inquiry commission set up afterward to assess the level of police violence. “I was caught in a trap of wild stone throwers who gathered in the empty yard near the Sephardic nursing home. Police were hitting and spraying water hoses.”

Nearly a hundred injured people were taken to the old Shaare Zedek Hospital, which at the time was located just down the street from the shuk. Other more lightly wounded people were treated at the scene. One seriously wounded man was forcibly taken from the hospital by police, against the protests of the doctor on shift. “He is accused of attacking a policeman,” they replied, and pushed the man, handcuffed and bleeding, into a patrol car to take him to the Russian Compound.

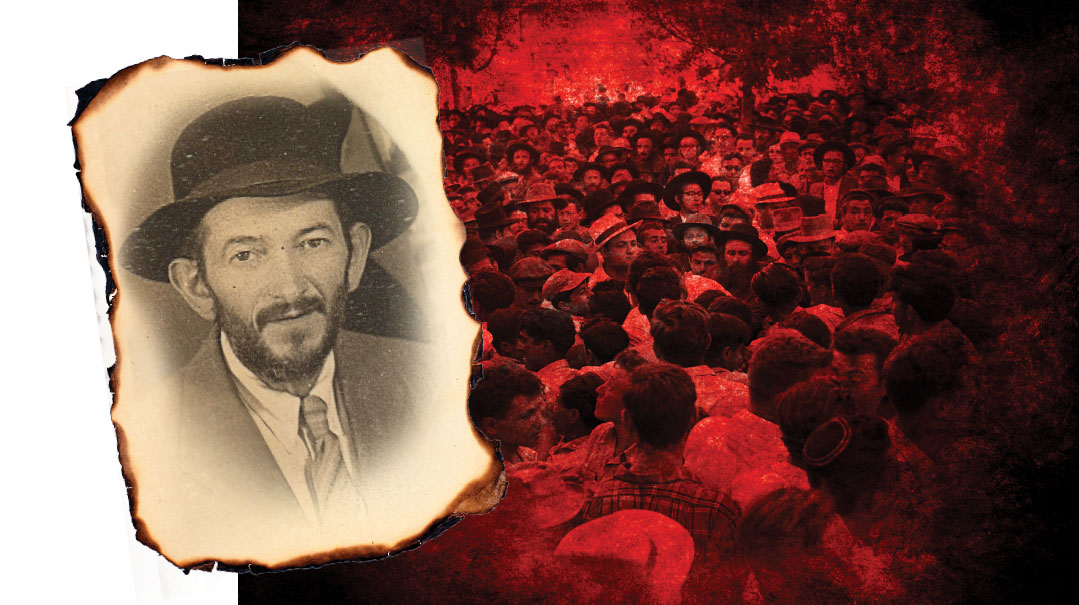

While most of the crowd stood on Jaffa Road in the area of Machaneh Yehudah, there were some breakaway groups who went over to protest in the Romema neighborhood where the vans to the beach departed. Among them was Rabbi Pinchas Segalov, a middle-aged Gerrer chassid who’d made aliyah from America in 1929, and who came to the demonstrations every week, approaching onlookers and explaining to them about the holiness of Shabbos. He’d often be detained for the rest of Shabbos and then released, when it emerged that there was nothing to build a case on. After one such incarceration, he wrote to Rabbi Amram Blau, “…baruch Hashem, I merited to get flogged and had to take to bed because of the honor of Shabbos….”

That violent Shabbos at the end of Elul, Reb Pinchas was standing on the edge of the sidewalk and watching in dismay as the police beat protesters. “Have mercy on them, mercy!” he shouted. One policeman approached him and punched him hard in the chest. Rabbi Segalov fell to the ground, hit his head on the edge of the sidewalk, and lost consciousness. He was brought to the hospital soon afterward, and passed away later that afternoon.

Israeli novelist Chaim Beer was an 11-year-old boy at the time. He grew up in an Orthodox Jerusalem family, and had come to the demonstration as a curious onlooker.

“I was just a boy, but I’ll never forget the intensity of the onslaught by the police,” he described years later in an interview. “The demonstrators thought they were simply going to a demonstration, but in the eyes of the police, they had crossed a red line. For the police, Jaffa Road and the entrance to the city were like the 40-kilometer security zone in Lebanon that you just didn’t cross. Demonstrating in chareidi neighborhoods was one thing, but to block the entrance to the city was another. The police acted as though there was a contract out on the demonstrators by the speed with which they began wielding their clubs and their wild charging into the crowd. I fled by the skin of my teeth, running all the way back home to Malchei Yisrael street where we lived — and I was a pretty chubby kid. To this day, I’m surprised that only one person was killed that morning.”

After that, the Brisker Rav warned against going to these demonstrations because the obligation to protest was not yehareg v’al ya’avor, one did not need to risk his life to do it. To those who claimed that there was still a need to protest constantly, he replied sharply: “You are allowing yourselves because you think the Zionists will have mercy on you, but I think they’re suspects in shedding blood.”

Rabbi Segalov’s funeral the next day was attended by thousands of people from all over the country, including numerous rabbanim and gedolei Yisrael. Eidah Hachareidis members stood next to National Religious politicians such as Yosef Burg and Zerach Warhaftig. Everyone realized that something critical had happened.

“I came like many others to the levayah, which was directed by Rabbi Amram Blau of Neturei Karta,” recalls Rav Menachem Cohen, rosh yeshivas Toras Chaim and the chairman of the Mishpacha rabbinical committee, who at the time was a talmid in Ponevezh. “Then I saw the Ponevezher Rav standing there, together with Reb Amram, and I was surprised, because Rav Kahaneman and the kanoim were known adversaries. He belonged to Agudah, hung an Israeli flag on his yeshivah on Independence Day, and had connections with the government. The kanoim condemned him in their proclamations and considered him the symbol of collaboration with the Zionist authorities.

“I was curious, so I approached the Ponevezher Rav and asked him, ‘Rosh Yeshivah, why did you make the effort to come from so far?’ I also asked if he wasn’t afraid of the kanoim. He replied, ‘If Pinchas Segalov gave up his life for Shabbos, I shouldn’t make the effort to come here, even if I’m taking a risk?’

“Then, when the hespeidim began, the rosh yeshivah said to me, ‘You know what? I also would like to speak for the niftar.’ I was very hesitant about what might happen. I doubted they would allow him to speak. But the Rosh Yeshivah had asked. I went over to Rabbi Amram Blau and said, ‘The Ponevezer Rav is here and he wants to give a hesped.’ I waited for a sharp reply, but to my surprise, Reb Amram immediately replied, ‘Of course, of course.’ He announced on the loudspeaker very respectfully that the Ponevezher Rav had arrived and honored him to speak. That just showed that indeed, the kanoim in those days really intended l’shem Shamayim.’ ”

That same day, the Israeli government announced that a “Jerusalem Commission” would be established to investigate what went wrong on that Shabbos of infamy. The committee would be headed by district court judge Eliyahu Mani, and its members would include Dr. Yitzchak Nebenzahl, future state comptroller (and father of Rav Avigdor Nebenzahl), Shaare Zedek director Dr. Falk Schlesinger, and Attorney Chaim Korngold, a Mapai member.

Naturally, there were entities who tried to prevent the yeshivah bochurim from coming to testify before the commission, including Jerusalem police commander Levi Avrahami, who many in the chareidi community considered the guilty party. But the bochurim wouldn’t be intimidated despite various fear tactics. They knew that if they’d capitulate, it would be a degradation to the memory of the chassid who gave his life for Shabbos.

“I went to the tefillah rally in the courtyard of Eitz Chaim,” described Chevron yeshivah student Chaim Rottenberg when he finally did give his testimony despite the intimidation. “From there, I went with the crowd toward the Romema intersection. As I headed back to yeshivah, before the crowd was dispersed by the police, I saw five officers going over to a thin man standing near a street corner in Romema. It was Reb Pinchas Segalov, who was not involved in the fights at all.

“But one of the policemen hit him very hard in his chest, and he fell backward, screaming. I wanted to run over to him, but at that moment, I was struck by a stone, and I got a deep cut in my head and fell down. Another bochur picked me up and carried me to the hospital — and there I saw the Jew who the policeman had hit lying in a coma on a stretcher.”

Another bochur who took the stand was a young fellow named Yehudah (“Yudke”) Paley, who would eventually become a prominent personality on the religious Jerusalem landscape. Rabbi Yehudah Paley, who passed away in 2012, was the founder of the Hebrew Mishpacha and a contractor who was heavily involved in creating affordable housing options in the chareidi sector.

Yudke, who was 18 at the time, was a regular at the Shabbos demonstrations, as per the instructions of his rebbi, Chevron rosh yeshivah Rav Yechezkel Sarna. In preparation for the publication of a book on Rabbi Paley’s life, his family was able to access the transcripts of the testimonies through the efforts of researchers Yitzchak Horowitz and Rabbi Yisrael Gellis. While the court documents weren’t officially classified, they weren’t readily available either — the violent riots were an embarrassing and uncomfortable chapter in Israel’s early history, and permission to access the official archives was slow in coming. When the family finally had them in hand, those papers shed light on a young bochur who would fight for justice at all costs.

Yudke began his testimony by relating what had happened on Shabbos parshas Shoftim, which was actually three weeks before Segalov was killed. He described how he went to the demonstration at 7 a.m. at the entrance to the city, where about 100 chareidim and close to that many policemen had gathered. Yudke brought up that week’s demonstration because that was the first time he saw police violence against the demonstrators, and it was his first encounter with Pinchas Segalov as well. He described how five policemen assaulted an 18-year-old bochur, apparently his friend from yeshivah. And then he spoke about Segalov:

“I looked over and saw Pinchas Segalov standing near the sidewalk, holding a piece of fabric in his hand, and explaining to the children how the flag is just a piece of fabric, yet the whole world accepts it as the symbol of the state and respects it. He said that the Torah, given at Har Sinai, was similar and explained why. Then a few policemen came over to him and asked him something, and then they fell upon him from both sides, beat him, and then climbed onto his back in order to push him into the paddy wagon.”

Attorney Korngold, who made no attempt to conceal his hostility, wanted to go back to the description of Segalov explaining to the children about the holiness of Shabbos.

“You said that Segalov had a piece of fabric in his hand. What was this fabric?” he asked.

“I imagine that it was an Israeli flag,” Yudke replied. “I don’t know. He took it out of his pocket and held it in his hand.”

“What did he say?” Korngold pressed. “That the flag of Israel needs to be respected?”

“That too,” Yudke said and then explained, “Segalov would say: This is a piece of fabric that the entire nation respects because they accept it as the flag of the state. So too the Torah and Shabbos — which Jews have died for — certainly need to be respected.”

Yudke then went on to describe what happened three weeks later, when he went out to demonstrate.

“By the time I arrived,” he told the commission, “the crowd had begun to walk toward Romema, so I joined them. But on the way, they collided with several groups of wild, secular young people and the hitting began.”

He described how the police selectively took sides, supposedly keeping order but essentially beating the chareidim while they moved the others a few meters over.

“And then,” he said. “they began to spray water. There were older people who couldn’t run, so the police specifically targeted them. I also saw a policeman go into the crowd and they began to scream at him, ‘Shame on you, why are you throwing stones at us?’ And he screamed back, ‘If Hitler didn’t finish you, then we’ll finish you!’ ”

Dr. Nebenzahl blanched at this last description. He asked if there were any grounds for the comment: “You said that the policeman mentioned Hitler. Did they first call him a Nazi?”

“I heard such screams,” Yud’ke said. “I don’t know if they were directed at this policeman, but I heard such screams after the police got wild and started beating people. It’s no wonder.”

Attorney Korngold questioned him about one of the bochurim who had been arrested for allegedly spitting on a police car.

“Did you see him spit on the car?” Korngold asked.

“No. I only saw them arresting him.”

“You don’t know if he spit or not?”

“No.”

“What do you think, did he spit?”

“I can’t imagine that he did. He’s a really quiet bochur. I think it was the first time he even went to demonstrate.”

“I have a signed confession from him that states, ‘It is true that I was there and I screamed “Shabbos” and spit on a car.’ ”

At this point, Yudke bristled. “They can also force a confession. They beat them up before they interrogate them, so why not afterward?”

“Meaning, you don’t believe him?” Korngold asked. Paley replied that indeed, in his eyes, it was a forced testimony, because he was a quiet young man.

“Are you a quiet bochur?” Korngold shot back. “I just want to compare.”

“He’s quieter than I am.”

“You’re more of a chevrehman?” Korngold asked.

“I didn’t say chevrehman, I said quiet,” Yudke replied, and then couldn’t help but laugh at the direction the questioning was taking — which infuriated Korngold. Still, Yudke tried to steer the testimony back to someplace significant, and instead spoke about the secular youths who came looking for a fight.

“How many of them were there?” Korngold asked. When he heard the number, he snapped: “And this handful came to fight with a thousand people?”

“They knew that the police would help them,” Yudke said. “And that’s in fact what happened.”

Despite the testimonies of half a dozen witnesses, the police claimed that since the body didn’t undergo an autopsy because the mittah was taken away, perhaps Segalov had sustained another injury prior to his fall, and that’s what caused his death. And so, in their conclusions, the commission did not negate the fact that there were policemen who behaved inappropriately, but decided that “the police should not be held responsible for the death of Segalov. The means that the police used were legal.” They explained that a person who comes to a demonstration has to take into account that dispersal may become violent, and that the police bear no criminal responsibility if that’s how they must handle the crowd.

It’s been 64 years, Jerusalem today has a chareidi majority, and yet the “status quo” has fallen victim to political correctness and has been eroded with nary a blink. And although there are many yarmulke-wearing officers in the police force, the suspicion and lack of trust is still there. But isn’t Jew against Jew the tragic, heartbreaking narrative of an Eretz Yisrael so many centuries before? The fight to bring G-d back into the picture is as old as the Chanukah story, when the Hellenist Jews sided with the Syrian-Greeks to ferret out all vestiges of spirituality from the Holy Land. Bayamin haheim, bazeman hazeh.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 839)

Oops! We could not locate your form.