Seventh Heaven

A new appreciation not only for the Seven Species of Eretz Yisrael, but for all the Land’s bounty

Photos: Menachem Kalish

Many of us have heard how, back in the 1950s, the Ponevezher Rav would visit the non-religious kibbutzim on the eve of the shemittah year and embrace the trees, wishing them a “Gut Shabbos” for their holy sabbatical year. I’ll admit I’m not a tree-hugger myself, but the combination of this shemittah year and the upcoming holiday of Tu B’Shevat — when the sap of renewal begins to rise, even as the trees look their worst — has ignited my passion for the incredible trees and fruits of Eretz Yisrael.

No Better Bokser

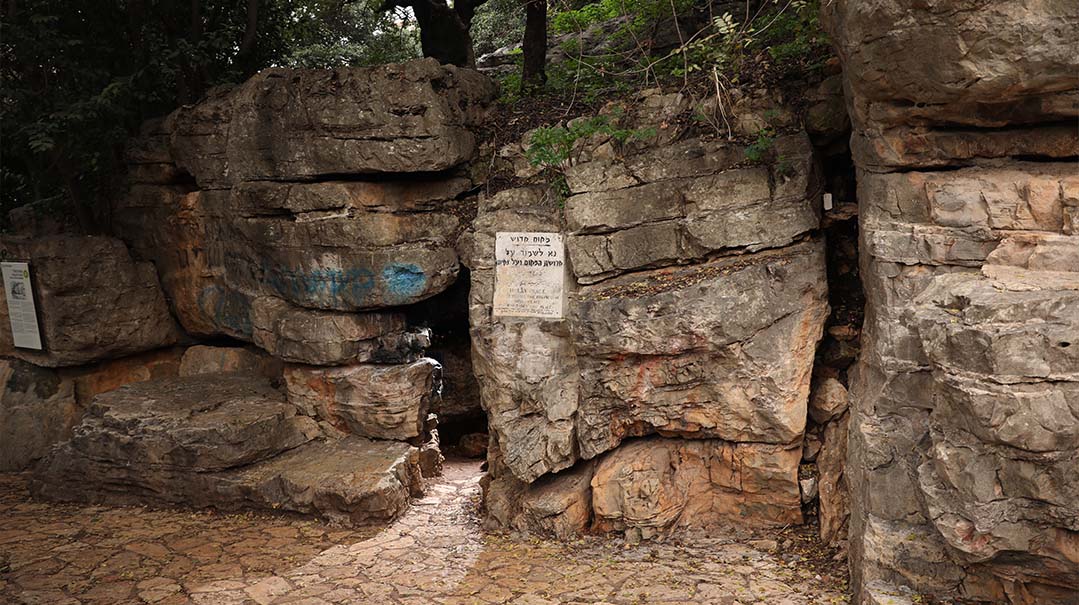

What do you associate with Tu B’Shevat? As soon as I hear the word, I think of bokser, those long, black, shriveled carob sticks my school would put in our Tu B’Shevat baggies. No one really wanted to eat them, though, and although they’re not part of the Shivas Haminim — the seven species for which Eretz Yisrael is praised (wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives, and dates) — those bokser snacks have an illustrious history in the Holy Land. When Rabi Shimon Bar Yochai, author of the Zohar, hid from the Romans in a cave for 13 years, he was sustained by a carob tree. And so, as mysticism and bokser go way back, what better place to begin our Tu B’Shevat tour than the Upper Galilee village of Peki’in, the traditional site of Rabi Shimon’s hideout cave?

Peki’in, today a mixed Christian, Muslim, and Druze village, has the distinction of being the only Jewish city with contiguous Jewish settlement from the period of the Second Beis Hamikdash until the present. Unlike Jerusalem and other cities where Jews had been expelled and banned from living, there was always a Jewish religious presence in Peki’in. Today, Margalit Zinati, 91, is the guardian of the ancient synagogue and the last remaining Jew in Peki’in, a member of a Jewish family who has lived in the village for centuries.

It is this unbroken Jewish tradition and life in the town that gives us precise knowledge about where Rabi Shimon’s cave is located. And wouldn’t you know it: As we descend the long staircase that brings us down to this holy cave, we see carobs all over. Various seismic shifts over time have changed the topography, so the cave today is more like a large crack between two rocks. The miraculous spring Rabi Shimon and his son drank from has also shifted down the hill because of the earthquake activity in the Galilee throughout the centuries. Yet there’s still a carob tree around the cave — the very spot where much of Rabi Shimon’s greatness in understanding the secrets of the Torah was achieved.

In the 1920s, Yitzchak Ben Tzvi, who would later become the second and longest-serving president of Israel, spent much time in the town researching its ancient origins. In his book She’ar Yashuv, he praises the lonely carob tree as a metaphor for the Jewish people in Peki’in and everywhere: “In their remote corner live the remnants of Jewish agricultural settlement that has persisted since ancient times, isolated and lonely like the ancient carob tree in whose shade they were sheltered. For hundreds of years they endured torture, and the hope of redemption and salvation did not leave them. It is a tree that symbolizes faith and perseverance throughout the generations.”

Hold Out the Olive Branch

As we travel from Peki’in in the direction of the coast, we pass by many olive groves. It’s not surprising, though, as we’re entering the biblical portion of Shevet Asher, who, in the blessings of both Yaakov Avinu and Moshe Rabbeinu, were given the blessing of olive oil. In fact, in Kabbalah, Asher is the tribe identified with the month of Shevat. In the Kabri archaeological park near Nahariya, the Israel Parks Authority uncovered many ancient olive presses from the period of the Second Beis Hamikdash, as well as one of the oldest wine presses thought to be from the period of the Avos. The Gemara tells us that it is from this region that the pure olive oil was brought for the Beis Hamikdash. It is this few days’ journey back and forth from Jerusalem that is the backdrop of the eight-day Chanukah miracle — that’s the travel time required to bring the pure oil from this region.

Ayala Noi Meir, manager of the family-owned Reish Lakish olive press in Moshav Tzippori in the lower Galilee, is Israel’s representative in olive oil competitions and in quality control consultations around the world. She is an official olive oil taster, and her well-honed palate can tell not just the difference in olive oil quality, but even in what regions and in what year the olives were grown. The olive press is named for the great Amora, who stated that the area of Tzippori is what the Torah is referring to when it mentions a “land flowing with milk and honey.”

Ayala shared how, despite the fact that Israel does not produce or export much olive oil, the olive tree is the most prolific fruit tree in Israel, with over 330,000 dunams of olive tree groves. And Israel produces the most varieties of olive oil, many of them award winning, with 17 different species grown here alone.

She also shared a few vital tips for all the olive oil users out there: The first is that olive oil is actually one of the most forged products in the supermarkets. It’s estimated that 70 to 80 percent of the commercial olive oil being touted as pure extra virgin is in many cases is not even entirely olive oil. It’s a very unregulated industry, in which a few companies have a lot of control and can pass off a lot of lesser-quality products.

One of the best ways to know if your olive oil is of a high quality, or even real, is in the packaging. Sunlight is the biggest enemy of olive oil, so it should never be kept in clear glass or even worse, plastic containers (the cheap oil in plastic bottles is generally lighting grade but not eating grade, and is often cut with benzene). People who care about their olive oil should purchase it only in tinted glass bottles.

The shelf life of olive oil once it’s opened is only about a year and a half, so huge Costco jugs are generally not the way to go. Olive oil shouldn’t be stored near a heat source, or where the sun beats down on it. Neither should it be kept in the refrigerator. Olive oil has tremendous health properties, and according to the Gemara, it’s even known to restore memory, so one who eats olives is advised to eat them together with its oil.

Worth a Fig

This year there are close to 4,000 farmers observing shemittah, and one of them is a fellow named Mordechai Binyamin of Moshav Elifelet, one of the few farmers in the country growing figs. Although it’s a shemittah year, he’s quite busy, as fig trees need TLC the entire year so that they stay healthy, and the fruits of his labor are distributed through the Otzar Beis Din.

While the fig tree produces only about two months a year, the work surrounding it is ongoing, from protecting the tree from insect infestation to the actual difficult process of picking the fruit (each fig needs to be examined by hand to see if it’s ready). He describes how much the weather impacts their annual crop as well — too much or too little rain, or too hot or too cold weather are all factors. He says it’s a miracle each year that the figs grow and develop, as there are so many forces out there trying to take them down. It gave me new insight into the pasuk, “Ki adam eitz hasadeh” — that man is compared to a tree. We as well face so many forces that challenge us and try to prevent us from flourishing

But the enemies his trees face are not just forces of nature. Finding laborers willing to work is becoming more and more challenging, as they must wear uncomfortable full body suits so they won’t get splashed with fig sap. And there have also been incidents of vandalism by neighboring Arabs who sneak in and either steal or damage the crops and then shake him down for protection money, which he has always refused to pay. The lowered tariffs on imports, coupled with rising water prices that make their product more costly, means that the prices for the export to stay marketable have made it unprofitable.

Yet despite all this, Mordechai tells us of the many miracles he has experienced — especially in this year before shemittah (shemittah for fruit begins on Tu B’Shevat). Besides his fig crops, Mordechai has a huge orchard of mangos and citrus trees of all types. He grows avocados, pecans, papaya, persimmons, and even grapes and olives. He proudly shows us many of these trees that this past year have more than tripled their yield, the brachah promised by Hashem for those who observe shemittah.

Before we take our leave, Mordechai insists we taste some of the delicious jams his wife makes from the various fruits. This more recent venture means that fruits such as figs, which have a very short shelf life, can be enjoyed all year long as a sweet and healthy condiment on bread and crackers. This burgeoning new business, though, will be shut down once the shemittah fruits ripen, as it is prohibited to engage in commerce with these holy fruits. But parnassah comes from Hashem, Mordechai avers, and he feels it’s a privilege to be able to spend his entire year maintaining his field so that all of those who wish to come and eat and share in the bounty will have what to enjoy.

Pomegranates for Geulah

Yitzchak Biton is an elderly Moroccan gentleman who lives in Chazon, a moshav neighboring my own Karmiel. For years he had a very successful pear farm, yet ten years ago he switched his crops and entered the then new and lucrative field of growing pomegranates. A few years ago, though, he realized that Israel’s pomegranate market had become saturated. Whereas when he started his farm, he could sell his pomegranates for eight or nine shekel a kilo, today they sell in the supermarkets for half that. While he might feel the pinch in his personal pocket, he attributes the bounty to the brachah of Eretz Yisrael — of the fruits growing as they never did before, which he insists is a sure sign of the Geulah.

Once Yitzchak reached retirement age, he decided to lease out his pomegranate groves. However, he actually takes them back for the shemittah year to ensure that they will not be worked, and so that he may merit the special blessing that Hashem promises for those who leave their fields fallow and unworked.

Setting a Date

We’re now going to take a little detour down south, and reach out to Doron Alush of Kesem Hatamar from the yishuv of Mevo’ot Yericho. Over the last 20 years they’ve been leaders in the planting of the date palm, that ancient Jewish tree of Eretz Yisrael.

Doron has been suffering from tourist deficiency syndrome the past two years, after he launched the date farm tourism arm of their yishuv. So although I’m not bringing him the crowds, he’s still happy to share with me how in ancient times this area was rich with date trees. But with the exile of the Jews from the Land, Eretz Yisrael remained barren for almost 1,900 years, and no date trees were grown. With the return of Jews to Eretz Yisrael, the early chalutzim brought back date trees, importing them from neighboring Arab countries and replanting them in the earth that had been waiting for them. While Israel, a small country in the big Middle East, doesn’t rank very high in the quantity of dates it produces, the Medjoul dates grown here are known throughout the world to be the most expensive and highest quality by far.

“The brachah has returned with the return of her nation,” Doron quotes.

What excites Doron most about this fruit, known as the candy of the ancient world, is that it represents the Jew, the tzaddik who is compared to a date palm (“tzaddik katamar yifrach”). But what’s the connection between a tzaddik and a date tree? He notes how there are only two biblical characters referred to as “tzaddik” — Noach and Yosef. Doron suggests that they are called tzaddikim because much like a date palm, they grew and flourished in the worst possible conditions.

Date palms grow on land that has very little rain; the earth here is very salty and doesn’t have many of the minerals that other agrarian areas do and that other trees require. The heat is overwhelming. Yet it is here that the date trees flourish the most. Similarly, a tzaddik flourished in the world of Noach, or on the 49th level of impurity in Egypt, where Yosef found himself. The secret to that power is the deep roots it has in the ground that hold it steady, and the tall leaves and branches that reach higher to the sky.

This will be the third shemittah cycle for Mevo’ot Yericho, but the people don’t seem stressed. They’re enjoying a more relaxed year of learning and of developing other products. Covid was actually a backhanded blessing for them as well, because although most of their tourism activities of date picking, date honey making, and even Doron’s personal latest innovation of kosher l’Pesach date beer came to a halt, the date fields became an ideal place for many corona weddings to be held, as halls closed and people were looking for alternate venues. Talk about setting a date for your wedding!

L’chayim, Rebbe

There’s no better place to complete a Tu B’Shevat tour than in the holy city of Tzfas, where the students of the Ari Hakadosh introduced many of the customs of Tu B’Shevat, including the structured Tu B’Shevat seder. We pass by the famous 600-year-old fig tree that sits in an empty courtyard and think of the ancient Kabbalists who would study under it and enjoy its fruits. And down the block from that tree, Yigal Biton’s Abuhav winery is like a beacon calling us to make a l’chayim.

Yigal is a very unlikely vintner and rather new to this business, or calling, as he likes to refer to it. Before finding his path to Torah and mitzvos, Yigal was one of the most successful deejays around among local and international event planners. But then he made a trip to Kiev and stayed by some Breslover chassidim — and came back a changed man. He gave up his successful business, took on a life of Torah and mitzvos, and met his wife who joined him in his journey. After a few years, found his calling making natural wines, with no preservatives or sulfides added in.

The Abuhav winery is named after the ancient shul around the corner from the winery, but the winery itself has its own special yichus, as Yigal found out when he purchased the property. It was once the home of the great Kabbalist and tzaddik Rav Shlomo Eliezer Alfandari, known as the “Saba Kaddisha”; he lived in Tzfas for a few years after serving as the chief rabbi in Turkey and as the Chacham Bashi in Damascus, and before he moved to Jerusalem to the Mekor Baruch neighborhood on a street that bears his name. The Saba Kaddisha’s students and colleagues were diverse: Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, the Sdei Chemed, Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook, and Rav Yisrael Odesser all considered themselves his talmidim.

The Saba was also very close with the Minchas Elazar of Munkacs, and they shared many a correspondence decrying the proliferation secular Zionism in the Holy Land. In fact, a few years ago there was a Munkacser chassid who came into the winery and purchased a few cases of wine for his rebbe. The Rebbe had once tasted the wine and exclaimed how delicious and special it tasted. When Yigal shared with the chassid that this wine was made in the house of the colleague of the Minchas Elazar, the Rebbe’s grandfather, the chassid understood what his rebbe must have tasted in the wine.

When Yigal excavated the courtyard of his house, he uncovered a 500-year-old underground cellar that had a wine cask that was hundreds of years old. That was a sign, he said, that this house was meant to restore the ancient Jewish tradition of making holy wine — and the cellar today is used to store his freshly made bottles.

As we sit out on the incredible porch of his visitor center with a breathtaking view of the Har Meron before us, he describes his learning curve in wine making: It began with a few hundred grapes in his bathtub, which admittedly didn’t turn out too well, but he read books and watched videos, and eventually taught himself the trade. And he says he has something even the best French vintners don’t: He has the holy soil of Eretz Yisrael and tefillos to the Divine Vintner.

But of course, he also has the soil with the volcanic rocks of the Golan, and the differing climates and elevations in the Galilee, where his grapes come from, bring out unique flavors and allow for a large variety of different grape species to flourish. Israel’s wines win international medals, as have Abuhav’s, although Yigal says he doesn’t really buy into these competitions. His clientele is looking for a more natural flavor without the added preservatives found in the more commercial wines. His only additive: the Tehillim he recites while his grapes are hand selected and pressed, and the Tikkun Haklali before putting them into the vats to age.

Wheat from the Chaff

We make one last stop, to the newest addition to the Tzfas tourist circuit: the Tzfas distillery, a whiskey store dedicated to whiskeys, gin, liqueurs, wine, and arak, all made here in Eretz Yisrael. The distillery was created by David Zibell, who made aliyah in 2014 with his family to the Golan Heights from Montreal. As a real estate broker in his previous life, he had the opportunity to drink a lot of whiskey, and his move to Israel gave him the opportunity to pursue his hobby and turn it into a thriving business. His whiskeys are gaining interest and traction in markets and among connoisseurs all over the world who are looking for a new and different taste.

The largest producer of whiskey in the world is Scotland, followed by the US and Canada. The wheat and barley crops from which whiskey is made have been growing there for centuries, and their tastes and processes are etched into stone and tradition. Yet David is a big believer that the purity of the water here, together with the blessings of the crops, can make a superior product.

But when he decided to try his hand at producing local whiskey from home-grown crops, he discovered that most of the wheat and barley grown in Israel today is for animal feed and matzah. Most of the wheat and barley flour used for human consumption is imported from Russia, where it is much cheaper and where it can be grown in greater quantities. Animal feed grains are rich in protein and short on starches, but whiskey production really needs the opposite qualities.

Yet David was able to find a local wheat producer who had high-end wheat, and all of his whiskeys are made from locally grown wheat and are fermented in Israeli-used kosher wine vats. Although finding local barley had been a problem, David discovered an immigrant from Colombia, an agronomist living his dream of restoring this blessed grain to Eretz Yisrael, who was looking for a partner. They’ve completed their first harvest, and are beginning testing to see if the product works. David also has an impressive line of non-grain products, including gins, arak, and rum, all kosher for Pesach.

David is helped along in his distillery’s visitor center by a friend and fellow Montreal oleh, Immanuel Bouzaglou, a local gallery owner, who, since the recent downturn in tourism, was looking for new opportunities. Immanuel had opened up a home and building renovation company — appropriately named “Tikun Klali” — and within that framework, found a storefront for sale in the old city that he thought would be perfect for a distillery. As the two began their renovations, they too uncovered an underground house and cellar that dates back over 300 years. After a bit of research, they discovered that house’s last tenant was Reb Yankel, the doctor of Tzfas who cared for many of the city’s sick, until his home, together with most of the city, was destroyed in the earthquake of 1837 and buried under the rubble.

Like a Tree of the Field

At the beginning of this year, the rav of Karmiel told me how, in the year of shemittah, one of the most important lessons we are meant to take with us is to stop and take a look at every tomato, every apple, every orange and to see the holiness in them. But the lesson doesn’t end there. For if man is like a tree of the field, and if there is untold holiness in a fig tree or in a date palm, then can you imagine how much holiness resides not only within those gibborei koach, the Jewish farmers among us, but within the person in shul standing next to you as well. This Tu B’Shevat, as we focus on the Land and its fruits, we await the day when all of the holy children of Am Yisrael will once again be returned l’echol mipiryah v’lisboa mituvah.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 894)

Oops! We could not locate your form.