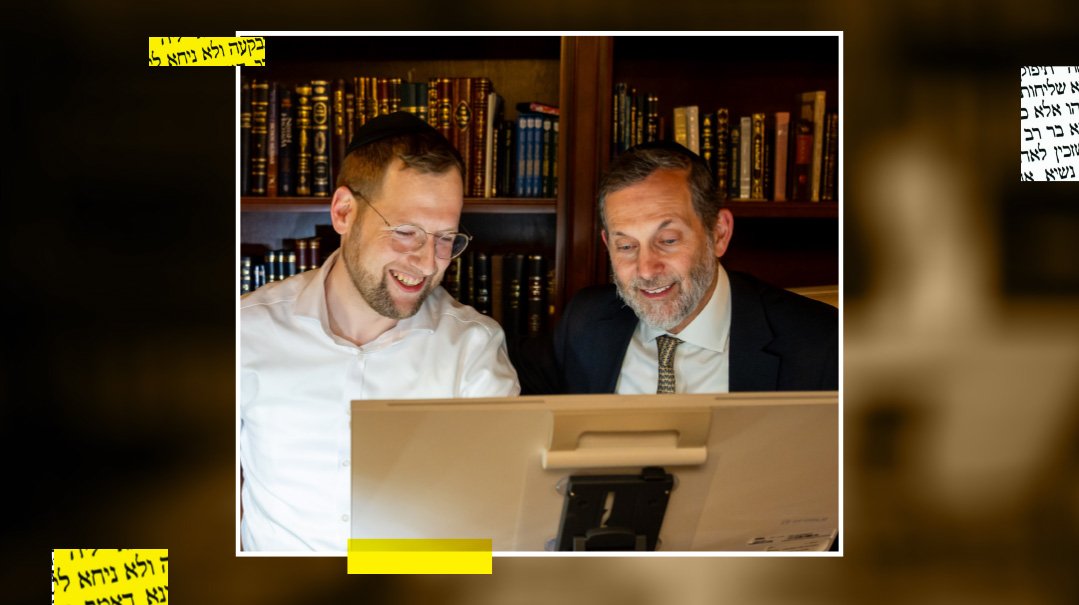

See for Yourself

It started as a gadget for a low-vision relative. Now the elderly can finally read again

Photos: Avi Gass

Yisroel Wahl was a successful chinuch advisor and business coach when a relative with low-vision could no longer read. And so, Yisroel took a deep dive into the world of high tech and startups in order to help, developing an idea much more complicated than he’d naively imagined. He could have shut the lights, but instead he saw it through — and brought many out of the dark

Lots of people have great ideas for how to make life easier, but most of those brainstorms never see the light of day. That’s why Yisroel Wahl’s breakthrough creation for those with declining eyesight stands out: A flicker of inspiration for a loved one became a focused pursuit, and his innovation is already brightening the everyday for countless others trapped in their own dim corner.

You might be familiar with Yisroel Wahl — a Lakewood business coach, behavioral health specialist, and chinuch advisor — from his popular podcasts and interviews about such motivational topics as overcoming anxiety, dealing with paralyzing overwhelm, becoming more decisive, relating to oversensitive children, and many other educational and business tools.

Yisroel might have continued exclusively on that trajectory if not for some serious optical challenges faced by a close relative who’d practically been born with a sefer in his hand, but who had now found himself struggling to read.

Yisroel is the kind of guy who seems to be in perpetual motion, a real doer and macher who’s not afraid to solutionize when a challenge falls into his lap.

The simple but heartfelt desire to help someone he loved return to his cherished seforim would soon send Yisroel on an uncharted journey, taking the seed of an idea and transforming it into a full-fledged startup company now producing life-changing devices for the visually impaired.

“Sight is life,” Yisroel says. “The Gemara compares a blind person to a dead person, because for so many people, sight is crucial for their ability to work, daven, and participate in society.”

While Yisroel’s new device, called OrahVision, cannot restore sight, it restores the ability to read for people suffering from macular degeneration, glaucoma, and many other forms of visual impairment.

Perhaps what stands out most about the system is how easy it is to use, even for elderly and tech-challenged users. The device functions like a digital portable shtender: You simply place any sefer or book down, and with the click of a button, the pages are reproduced perfectly for those struggling to see. The device sits in the desk, and the pages appear on-screen in sharp, high-contrast clarity. Users can zoom in, flip pages, and read comfortably without straining their eyes.

“For people who have been struggling with vision issues and haven’t been able to learn in a long time, this is so simple,” Yisroel says. “The program automatically fixes the curvature of the page on the spine, and with just a touch, expands or shifts the text from side to side, allowing you to move in and out, move between pages, and have a full shtender-like experience, as if you’re holding the sefer.” And just like a regular desk shtender, the angle of the incline can be adjusted.

“This is essentially what we wanted to accomplish when we set out,” Yisroel says, “and this alone solves most reading struggles. But then we even took it further, adding other capabilities. Users can now speak to the machine, and through AI, can have the page explained or read to them as well.”

For the new, happy users, it makes the difference between being limited and being able to pay bills, opening a sefer and reading it with ease, or simply enjoying a magazine or novel. For Yisroel, it became a journey into the world of technology, AI, and creating a brand-new startup.

When Yisroel began looking into ways to help his relative read again, his first move was to reach out to Nachum Lehman of CSB Care, an organization that provides services for the visually impaired, including very sophisticated systems for ALS patients and others that catch eye movements and even talk in the voice of the patient. Lehman was able to suggest what was available at the time — some low-vision devices that were basically magnifiers — but that required the user to turn dials to zoom in and move the paper back and forth.

“My grandmother had something like that,” Yisroel says. “But by the time she managed to decipher a piece of mail she was worn out. I thought, ‘Is this really where we’re still holding in 2025? Why isn’t there a better way to capture an image and manipulate it by touch?’ I naively thought it would be an easy task, but I soon learned that the tech innovation required to do this was exhaustive. Besides, there was very little motivation for companies to produce something new, since the old devices were mostly paid for by grants.”

I Didn’t Choose This

For over a decade, Yisroel has been helping businesses promote their visions, yet launching his own startup was a journey he never anticipated. “I had an idea that really didn’t seem too complicated,” he says. “But I had no idea what I was getting into. I jumped off a cliff without a parachute.”

Yisroel was best known for working with kids and mental health, but explains that running a tech startup isn’t really as much of a career pivot as it looks like.

“The truth is I never chose this,” he says. “When someone I loved started losing his vision, I dropped everything to help him. I had an idea, and I tried it. That led to our prototype, the first AI-powered platform that makes reading seamless for low-vision users without the outdated hardware the market has been stuck with for decades. And when it worked, it didn’t feel like a ‘project’ anymore. It felt like something I had to do for other people, too. I then built a team of engineers and grew this into a full startup. One person turned into another. And then another. And it kept growing in a way I never planned. So when people ask how I went from therapy work to building OrahVision, the real answer is simple. There was a need that had to be solved. And I’m watching this grow in real time together with everyone who’s walking alongside me.”

At the outset, Yisroel had zero experience coding, knew nothing about building apps, and says, “I thought that I could somehow build a simple app that would do what nothing in the low-vision tech world did. But both I and our team of software engineers have come a long way since those early days just over a year ago.”

In the fall of 2024, Yisroel wrote a post on LinkedIn to ask if anyone was interested in working on this problem, writing: “I am looking to hire a skilled developer to create a real-time text enhancement app for Android or iOS. The primary function of the app is to magnify and clarify text from physical books (primarily Hebrew seforim).”

To his surprise, a rebbi and clinical social worker from Toms River named Yedidya Pool reached out. “I can send you an MVP [minimal viable product] soon, if you like,” he answered.

Yedidya is also a computer whiz who taught himself programming without any formal training, and as it was bein hazmanim of Succos and he had a little extra time, he would be happy to give it a try.

“I would code from 7 p.m. to 3 a.m.,” Yedidya relates. “We had a very basic prototype by the end of Succos, but we saw it had potential. It was already much better than anything on the market.”

For Yisroel, though, it meant having to take a deep dive into the world of vision challenges.

“There was so much we had to get right,” he says. “For example, when you put a book under a camera, the curvature of the book is difficult to translate into a flat image. You have to account for low lighting, and sometimes the quality of the paper or the contrast is poor, which is problematic for people with low vision.”

Yisroel and Yedidya improvised as they went. “Yisroel had all kinds of ideas for features, for design, even details like naming buttons,” Yedidya says. “I had to bridge the gap between the features we wanted and the features we really needed, and negotiate the tradeoff between adding features and maintaining simplicity.”

The project pivoted many times. For example, an initiative to allow the screen to rotate was nixed after it became clear that most people just wanted to use the device in standard landscape mode.

Worried that he might be putting energy into a project that existed already, Yisroel flew off to the CSUN Assistive Technology Conference in California to check out what was already on the market, but nothing of the kind existed.

Meanwhile, another person who reached out was Bari Azman, a frum entrepreneur from the Five Towns who spent almost seven years helping with marketing and the business end of his father’s ophthalmology practice in Baltimore. Bari was enthusiastic about the possibilities in this new tech, and after Yisrael filed for a patent, Bari has been working with him in marketing and sales.

The Real Test

“Everyone has good ideas,” says Yedidya. “Every coffee room in Lakewood is full of guys with great ideas. But the move from idea to execution is the real test. So you work 18-hour days and use whatever works, even if it’s messy at first, and you’re always in contact with users to get feedback.”

Yisroel notes that since their specific product is a software, there’s theoretically no end to the features and customizations that can be added, based on user needs — an advantage that never existed in the old-time magnifiers. For now, however, he’s still focused on what would be helpful to most users, many of whom are not tech-savvy and just want to be able to read again.

At the beginning of the journey, Yisroel still had doubts about the product’s viability.

“At first, I kept asking myself, ‘Will this actually help the person I love? Or did I just throw away everything I built over the last decade in order to chase an idea that might never work?’ But then it started helping people — really helping them. I watched people read again. I saw lives change.”

In the beginning, profits were the last thing on their minds. “We didn’t begin this as a business,” Yisroel says. “I was putting in my own money. But startups eat up money at a staggering rate. We soon realized we needed more backing to make it work.”

As time went by, Yisroel began assembling a larger team of advisors and investors. Dr. Daniel Roth, a nationally distinguished retina surgeon who has also authored papers about magnifying devices, reached out to Yisroel several months ago, after a mutual friend sent him a video demonstrating the device in the Lakewood Scoop. Now Dr. Roth has joined the team as Chief Medical Advisor as well as an investor.

Dr. Roth, who maintains a busy practice in Toms River, says the system will be a boon for low vision users because it is so user-friendly and effective. “The old magnifiers were so cumbersome and provided a very limited field of vision,” he says. “Users would get frustrated and just give up.”

Another recent addition to the advisory board, as Operations and Procurement Advisor, is Bar Massad, the former VP of OrCam. OrCam was an Israeli company that was poised to launch a one and a half billion-dollar IPO close to two years ago, also producing assistive technology for vision. But as AI moved to a stage where it was no longer hardware-dependent, the company faltered and ultimately shut down.

“Our product uses AI but doesn’t need its own device for it,” Yisroel explains. “We currently sell it packaged with hardware, but ultimately, we build software that could be used on any compatible device.”

Like Holding a Sefer

It’s time for a hands-on demo of what OrahVision can really do. He places a sefer under the scanner, clicks a button, and the open page appears on the screen enlarged. There are no passwords to enter, as that proved to be an obstacle for some elderly clients. You can touch the screen and move the image back and forth, zoom in and out, or move to a different section of the page.

“You know, when I first had the idea for this system and told a certain talmid chacham who was becoming vision-impaired about it,” Yisroel says, “he objected, telling me, ‘But I need to be able to hold the sefer!’ So I started with a big screen that sits on a shtender, but when that was too bulky, I thought — why not make the shtender its own screen?”

The monitor uses a touch screen, so the user can zoom in or out to make the text bigger and move back and forth easily between sections by moving a finger. The user also has an option to change the screen color from black and white to other choices.

“People with macular degeneration often do well with inverted colors or yellow letters on a navy background,” he says. “The contrast is easy to read. Other people with Irlen syndrome, which usually requires special tinted glasses to allow them to read, can read from these screens without the glasses because of our customizable color options.”

When it comes to Hebrew reading, Rashi script is especially challenging for the vision-impaired; it tends to be printed very small and squished together. But this screen allows users to enlarge it and read it more easily.

And then there’s another high-tech interface. The user can ask “Orah,” the AI virtual assistant, to read a page aloud in English.

To demonstrate, Yisroel clicks a button. A woman’s voice says, “Hey, I’m Orah. How can I help?”

“Explain this page to me,” Yisroel says.

We’ve randomly pulled off a book from the shelf, Rebbetzin Esther Jungreis’ Life Is a Test.

“This page contains text from a book that is likely a memoir or novel,” Orah says, “in which the narrator reflects on personal experiences, including religious traditions, relationships, and observations about people.”

When he tells Orah, “Read the page to me,” she doesn’t cooperate. She just repeats the summary. Yisroel frowns. “It’s a new version. Our reading option hasn’t been activated in this version. I’ll have Yedidya work on it.” he says. “We’ve been working on the system, and I think we created a glitch.” He pulls out his phone and sends a voice note to Yedidya to ask him to address the problem.

The reading feature means more than being able to listen to a biography or novel; the device can read bills to a client, telling him or her how much is owed and when it is due.

Today, OrahVision sells for $3,600. “It sounds like a lot, but really isn’t,” Yisroel says. “The monitor and the camera alone cost $1,800. We don’t manufacture the hardware ourselves. Our largest cost, though, is assembling a top-notch software team to build the software.”

No Safety Net

Like many a startup entrepreneur, Yisroel Wahl was never one to fit into the usual boxes. . He was born in Chicago, then moved to Lakewood with his family where he attended school, learned in Yeshiva of Long Beach and in Rav Mordechai Dick’s yeshivah in Monsey, and later spent years in BMG learning halachah.

After he married, he moved into education after tutoring in schools, focusing on children with behavioral issues. He gradually expanded into deeper work and eventually moved into the therapeutic side, and began to pursue a master’s degree in social work. But then, after a personal emergency, he was forced to take a break.

“Sometimes I wonder if I would want to go back and restart it,” Yisroel says. “But I’ve become successful over the past thirteen to fourteen years, and in retrospect, it forced me to rise to what I became. Not having that certification to rely on left me with a certain insecurity that actually pushed me to always do more, to know more.

“When you complete a professional program, you come into your field following certain protocols, and if something doesn’t work, at least you know you followed the protocol. It’s easy to let go and rely on doing what’s expected. But I didn’t have that, which made me work endlessly to study the latest information and find solutions. Without that safety net, I felt pushed never to stop growing.”

And he did. He soon supplemented his work with children with videos about successful chinuch. From there, he moved into business coaching for entrepreneurs, with a specific focus on the emotional blocks that hold people back. The coaching led to a podcast entitled “Million Dollar Barrier.” Yisroel still has some coaching clients, but the lion’s share of his time these days is devoted to OrahVision.

We Both Cried

While Yisroel and his investors expect OrahVision to change the world of low-vision tech, he says the greatest gratification he derives comes from its power to change the lives of low-vision clients. “We didn’t begin this as a business,” Yisroel says, “and the biggest payoff isn’t money.”

His very first paying client was a 75-year-old man. He took a Chumash and put it under the camera. When the image came up and he enlarged it enough on the screen so he could read it, he cried with joy. “I haven’t learned the parshah or done shnayim mikra in four years,” the man he said.

“I cried, too,” Yisroel relates. “It felt like such a zechus to be able to enable his learning.

“Later I got a call from someone whose father had begun to deteriorate since his vision began to decline. He was sleeping all the time and losing interest in all the things that mattered to him. His son asked if I could help, so we set him up with the system. A week later, I got a call to tell me how his father came back to life. He was now able to read books, pay his bills, and look at pictures of his grandchildren. The world opened up for him again.”

Yisroel believes that many elderly people could avoid depression and cognitive decline if they could access reading material again. “Reading has been shown to be more powerful than listening to audio content in slowing decline,” he says.

Another person contacted Yisroel to tell him that Chacham Yosef Harari-Raful, rosh yeshivah of Ateret Torah in Brooklyn, had been delivering shiurim by heart because he was no longer able to read the texts. He gave him the number of the Chacham’s wife, who told Yisroel that she didn’t think the system would work for them. She thought it would be too complicated and technical for her 92-year-old husband.

“Don’t worry, our whole focus is making this simple and easy to use,” Yisroel reassured her. He convinced her to let him come by and show it to them. Chacham Yosef was enchanted. “He was thrilled, heaping brachos on my head. It was incredible to see someone who has dedicated his life to Torah study once again be able to read easily. It was incredible to see it live.”

Rav Reuven Feinstein in Staten Island had been having difficulty seeing as well, and became yet another client. “He now uses the device every day to learn and give shiur,” Yisroel says.

We Jews are not only people of the book; we are people of great generosity and compassion. One system was delivered to a client who had heard about the device and discussed it with a friend in shul. “It sounds amazing. It would make all the difference for me,” he said. “But I just can’t afford it.”

Unbeknownst to him, the conversation was overheard by a man standing behind him, someone for whom the price tag was not a deterrent. This person quietly arranged to purchase a device for his fellow mispallel.

Interfacing with so many low-vision clients has given Yisroel a new level of appreciation for his own eyesight.

“It’s so easy to take our sight for granted,” he says. “We get a cold and suddenly we realize how much health matters. But sight? It’s fundamental. Regaining the ability to read is life-changing, and I’ll never forget the people we’ve worked with whose lives were changed. It’s made all our efforts worthwhile.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1088)

Oops! We could not locate your form.