Road Map to the Future

Four experts discuss the challenges confronting the young men of our communities

Your son has just finished a year learning in Eretz Yisrael, or perhaps in a beis medrash closer to home, a time when he should be thinking seriously about the direction of his life: future learning, a career, marriage. Yet so many young men have no idea how to go about taking those next steps. How can we encourage today’s young people to be resourceful in preparing them for the successful “launch” to the next phase of life? How can a bochur discover who he is, in addition to his role as a talmid? Certainly, those who wish to continue learning should be encouraged to do so, but what about those who don’t see the beis medrash as their long-term goal — how do they navigate the next few years?

We’ve brought together four experts to discuss the challenges confronting the young men of our communities and how they can create a road map to guide their future

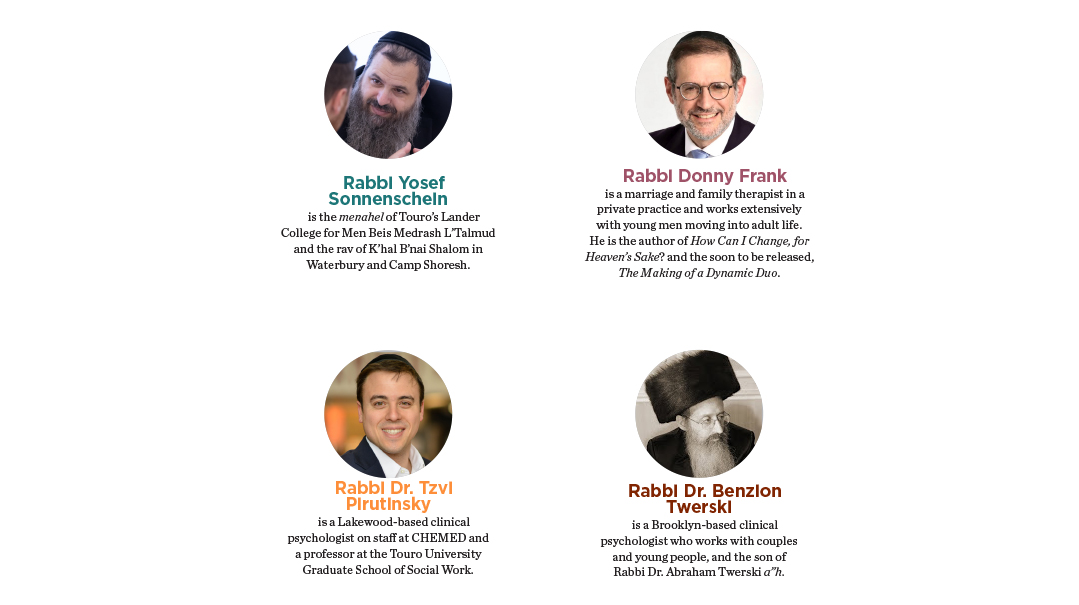

Rabbi Yosef Sonnenschein

is the menahel of Touro’s Lander College for Men Beis Medrash L’Talmud and the rav of K’hal B’nai Shalom in Waterbury and Camp Shoresh.

Rabbi Donny Frank

is a marriage and family therapist in a private practice and works extensively with young men moving into adult life. He is the author of How Can I Change, for Heaven’s Sake? and the soon to be released, The Making of a Dynamic Duo.

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Pirutinsky

is a Lakewood-based clinical psychologist on staff at CHEMED and a professor at the Touro University Graduate School of Social Work.

Rabbi Dr. Benzion Twerski

is a Brooklyn-based clinical psychologist who works with couples and young people, and the son of Rabbi Dr. Abraham Twerski a”h.

How do we help bochurim navigate the transition from teenager to adult?

Rabbi Twerski: The first step is to encourage boys to be doers, not “possessors.” The level of luxury in our society is a challenge, and we need to teach our children, by example, that wanting something “because everyone else has it” is not a Torah value. Instead, they have to learn not to confuse wants with needs. A mature person is capable of doing without when the situation calls for it.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: I believe that as a community we’re doing a very good job taking care of our children. Where we sometimes fall short is in guiding them to become adults. They’re easily paralyzed by decision-making and have trouble taking on responsibility. This means refraining from merely “paskening” on their questions, rather, taking them through the decision-making process and helping them learn to make their own decisions.

Rabbi Frank: Being away from home and away from parental influences doesn’t mean one will necessarily use that freedom to learn how to make good decisions and take responsibility. Many will simply follow friends and preplanned systems, rather than make personal choices.

When a bochur reaches maturity, goals should start emerging from within, based on personal values, strengths, and weaknesses, and should not be limited to what’s being imposed on him from without.

Parents must be mindful to encourage their young adult children to grow up, and certainly not block that path.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: There are boys who will come with questions about potential shidduchim or life paths and tell me, “My mother wouldn’t permit me to make this type of choice,” or, “My father wouldn’t allow it.” I’m tempted to say, “If you’re in shidduchim, that means they think you are mature enough to be married… shouldn’t they allow you a voice in your decision making?” Instead, parents should be helping their children learn how to weigh the pros and cons, listen to their own gut feelings and enabling them to make their own choices. Once parents frame the decision-making process, they should be telling their children, “We trust you to make your decision.” We can help our children and talmidim make choices not by deciding for them, but by clarifying the issues and walking them through the consequences.

Rabbi Frank: I attended Yeshivas Ner Yisroel, and Rabbi Yaakov Weinberg ztz”l would talk a lot about personal responsibility. For example, an askan called him about a particular community challenge to find out what he should do. Before answering, Rav Weinberg asked him, “Well, what do you think?” When the askan admitted to not having really thought it through, Rav Weinberg asked him to call back the next day with his thoughts, at which time he’d share his.

Dr. Pirutinsky: We have to teach our children to learn to tolerate negative emotions without jumping in to fix things for them. Let them make bad decisions! They have to learn that failure is always a possibility and they have to be ready to tolerate it.

This issue isn’t limited to the frum community. It has been a trend in the US over the past 100 years that adolescence is being extended longer and longer — in fact, the frum community generally lags behind the secular world where such trends are concerned. As a society, our tolerance for problems of any sort has gone way down. We expect perfection, and parents are quick to step in if something seems to deviate from that.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: A mother once called me to say that her son had been suspended from camp because he’d been caught drinking the very first week. She asked me to intervene on his behalf. I said to her, “Are you sure you want me to intervene? Is that the lesson you want him to learn, that he doesn’t have to respect the rules because someone will bail him out? Will that teach him achrayus?”

That said, a parent shouldn’t respond to a situation like this by telling the child, “Well, good! Now you’ll learn your lesson!” They should be compassionate and understanding that the path of growing up is littered with poor decisions, and that misjudgments are part of the process.

Dr. Pirutinsky: Yes, a parent can say instead, “I’m sorry, and I know this is hard, but you broke a rule and these are the consequences.”

We hear in the secular world that many young men “fail to launch” — they just can’t seem to grow up and pursue serious adult life in terms of career or marriage. Are we seeing that in our circles, too?

Rabbi Sonnenschein: I can’t say I see this all the time. Most young men I meet are energetic and motivated. But I do get the occasional call from parents who say that their son isn’t doing much of anything — he never seems to go anywhere, doesn’t finish the things he starts. Many of those cases involve overbearing parents who make all the decisions for their son, and the result is a kid who remains childlike instead of having the ability to set real goals.

Rabbi Twerski: I knew a couple where the husband was a workaholic, and when his wife complained, he agreed to take the family on a Sunday trip. They all got in the car, and then his mother called and told him she needed him to buy her sugar for baking later in the week. He canceled the family outing to go buy her the sugar.

Rabbi Frank: It’s not just a matter of overprotective parents. There’s a system-wide inability to avoid tension and failure. Instead people seek ways to simply chill and feel good.

When a girl returns from a year in Eretz Yisrael, she’s dropped into life and forced to make important decisions. She can’t keep coasting because there is no more school or structure within which to coast. She has to get a job, enroll in a degree program, and begin shidduchim. She needs to figure out how she’ll spend any extra time she has. On the other hand, boys in our circles stay in yeshivah and continue learning.

Now, if that’s the right path for him, he should stay there. But even for him, there are decisions to make. There are goals to develop. Notwithstanding what friends are doing and where they are going, where is the best place for him? What is the best style of learning for him? What learning goals will he develop for each and every zeman that he is fortunate to be learning? Not a single zeman should be taken for granted and entered into haphazardly.

I personally am a big believer in tests, like in the Dirshu programs. They provide real accountability.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: On the other hand, our metrics of measurement are so limited. When a bochur is in tenth grade, what are we measuring? We see who is smart, who’s frum, who’s athletic, who’s fun. Our society is not as good at measuring who’s sensitive, who’s artistic, who’s caring or resourceful. We could use a fuller spectrum for looking at talmidim and value them for their unique kochos.

Rabbi Frank: Rav Weinberg used to lament the fact that in our competitive environment, where success is relative, one’s success and self-esteem necessarily comes at the expense of others. Therefore, if a boy in yeshivah will never be the biggest lamdan, masmid, baal chesed, or whatever other category that fits his circles, he’s doomed to a life of low self-esteem, and possibly depression.

Instead, Rav Weinberg would say that real self-esteem isn’t dependent on being the best, or unique — both of which are relative to others — but in making good choices and being a true eved Hashem. Those are real, inner metrics. And, thankfully, anyone can achieve them.

There’s a boy I knew who had been a leibedig teenager, and went on to learn in Israel. It was a year of “Purim meshulash,” where most of the boys found ways by which to “celebrate” for three straight days. His yeshivah had offered learning incentives, and this boy had goals he needed to reach by the end of that week. It wasn’t going to work out to run around with his friends. So he stayed back. When I heard that story, I sensed that he had turned a very important corner in his road to adulthood.

How can we identify when a boy is floundering?

Rabbi Sonnenschein: It’s not easy. There are boys floating through the system who fall between the cracks. Sometimes they’re held back because they’re missing the right academic or social tools — and sometimes there are mental health issues, such as anxiety or trauma, which are paralyzing them. Identifying these issues boils down to the bottom line of all of chinuch — relationships, relationships, relationships. At home and at yeshivah, we must endeavor to know our boys. The fact that we deliver a shiur to them nowadays does not constitute a relationship.

Rabbi Twerski: Many boys become masters of leading a double life, so parents have to be open to hearing that maybe their son has another side to him. They will hide their fears, their shame when something isn’t right. It’s a huge task for yeshivah staff to attend to every bochur, to his emotions and issues, but if a rebbi or mashgiach sees that a boy is wearing the same clothing every single day, or doesn’t smell good, he needs to make it a priority to have a conversation to find out what’s happening with him — a conversation with no judgment.

Dr. Pirutinsky: Failure can happen at any stage. When people come for therapy, it usually means they have a serious problem that’s keeping them from moving on. But problems can arise anywhere along the way. For example, a kid might have done fine in elementary school, but his ADHD is creating serious challenges when he gets to high school. Or he might have some social issues that only emerge when he starts shidduchim. He’ll get stuck because the next step requires addressing individual challenges that would otherwise be debilitating. Yeshivah is a very structured setting where you don’t always need interpersonal skills, but you do need them to make a success of marriage and often a career.

How can we encourage young people to become more resourceful?

Rabbi Frank: I see kids today who lack initiative and resourcefulness. In my day, when we discovered the game of hockey, we played with broomsticks and rotten apples until we found a way to get real equipment. Without having had Amazon and one-click same-day delivery, everyone from our generation has their own stories of resourcefulness.

But today it needs to be all there for them. We can’t expect them to initiate or invest effort — even to play football. I remember one rebbi telling me that, in order to get his mesivta students to play football, he’d have to personally put out the cones. He said that if he didn’t set it up and have it all ready to go, they simply wouldn’t play.

Dr. Pirutinsky: Today, kids may be resourceful in other ways — they learn their way around tech or other areas. But still, if parents are always jumping in to fix things for them — since we have such a low tolerance for discomfort or suffering today — they really won’t develop resourcefulness.

Rabbi Twerski: Parents tend to think they’re older and wiser, so they should be making decisions for their children. Instead, they should be teaching their children to walk without holding someone’s hand.

We know the weaknesses. Tell us about the strengths this generation brings to the table.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: On the whole, this generation is talented and intelligent. They often surprise me with their insights and emotional subtlety and sophistication. They’re significantly more emotionally aware than we were at their age.

We spend too much time bemoaning the loss of the talents and kochos of yesteryear’s bochurim. This is unproductive and not motivating. We need to help our students recognize what they can bring to the table, and the unique talents that this generation’s talmidim have. As the baalei mussar have said, knowing one’s maalos is significantly more important than knowing one’s chesronos. This isn’t feel-good, new-age psychology, but a stepping stone to confidently engage in one’s future.

Rabbi Twerski: This generation has grown up with technology, and that’s a risk but also a gift, if we provide guidelines for how to use it safely. Young people also have direct access to so much historical information to learn from and relate to.

What is the most effective way for a rebbi or rav to reach young men today?

Rabbi Sonnenschein: Coming at young people with an attitude of “setting them straight,” or telling them what they should be thinking or feeling is doomed to failure. Bochurim are sensitive, and an approach that includes sarcasm or sharp criticism is a failed venture. We should also convey that they have a lot to add to the conversation, and be eager to learn from them, too.

Rabbi Twerski: Focusing exclusively on yeshivah curriculum or shul learning isn’t really effective. A rebbi or rav has to be able to read them emotionally, which doesn’t always work in a group setting. Academic success is secondary to creating fulfilled, happy Torah Jews. Rabbi Trenk a”h was a legend because of his tremendous, exemplary love for talmidim and his ability to reach them.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: Talmidim see authenticity in a second, and it makes a world of difference. They’re good at understanding the messages between the lines, good at sensing if we’re perfectionists or emotionally needy or unprepared to be honest about our mistakes.

That said, rebbeim and therapists have different roles. A therapist doesn’t bring himself into the therapist-client relationship. But it’s very helpful for a rebbe to bring himself into the relationship — his true essence, his vulnerable self, of course, with proper boundaries that are appropriate for the rebbi-talmid relationship.” This means that he’s absorbed more than the information. He’s absorbed a way of thinking. It comes down to being real and growing as people ourselves, and our talmidim sense this.

Rabbi Frank: Raise your children to seek guidance throughout their journey in life, and specifically to develop a connection to a rav who can offer an eitzah and hadrachah. My father a”h had a deep respect for rabbanim and talmidei chachamim. Besides role modeling it for us, he actively encouraged us to respect them as well. For example, when were children, he would make sure we’d wish the rav at any shul we’d attend a Good Shabbos. When we’d have halachic questions, he’d encourage us to ask them directly to the rav.

We should not lose sight of our limitations and tendency to see things as we want, and recognize when we need a wise and objective daas Torah to help us navigate challenging situations.

Of course, not every rav will fit the bill. It’s important to find the right fit, someone who understands you and your situation, and is capable of dealing with the questions you’re presenting him.

To an outsider, it often looks like the yeshivah system churns out cookie-cutter alumni, dressed in identical white shirts and black hats, who have studied the same material and been oriented toward the same life goals. How can a bochur discover who he is aside from his role as a talmid?

Rabbi Frank: There are lots of assumptions about what one should be doing at every step of the way. Learn so many years before going to Eretz Yisrael. Learn this many years in Eretz Yisrael. Go to this yeshivah. Come back to get married. Go back to Eretz Yisrael — maybe even to a certain neighborhood in Eretz Yisrael — for X number of years. And then… we’ll see.

My take on this is that it might very well be a plan… for the one for whom it makes sense. But how does one determine that he’s the one?

That said, I’m not a revolutionary. And I certainly will not work to upend this trend and lead people away from learning.

But is it okay to have a discussion before each step is taken? Can parents — and if not parents, at least someone else who will faithfully ask what a parent would — ask their children why they think the next step will be in their best interest, how it fits into their overall avodas Hashem, and how they intend to make it successful?

Can a parent be afforded the sense that the tuition they pay for their child’s year or years in Eretz Yisrael will be a financial investment for his future, rather than a financial burden to their bank account?

And if it’s about the part of the plan that relates to where the child chooses to live after he marries, can parents engage in a mature conversation to see whether or not it’s the kind of place that will help facilitate better shalom bayis and help them establish a solid home b’kedushah v’taharah?

Rabbi Sonnenschein: Let’s make sure not to limit our children to the specific path we ourselves have taken within the expansive, limitless world of Torah. If your child is discovering a path to Hashem that is emesdig and authentic, that’s a nachas, even if it diverges from the path you yourself have chosen.

Rabbi Twerski: A rebbi who is truly connected to his talmidim will be aware of the strengths each one brings to the table. He can help direct them to different paths in limud Torah or perhaps outside klei kodesh. I knew a guy in yeshivah who loved to draw and did art work with amazing detail. His rebbi saw his drawings in his room one day and exclaimed, “You are really talented! Can I help you get training to be a sofer?” In the end that boy didn’t become a sofer, but he does calligraphy and artistic kesubos. He’s basically still in klei kodesh, using his talents for Yiddishkeit.

The mission of yeshivos today is to create alumni who value Torah and mitzvos as a way of life. We need roshei yeshivah, but every talmid should have the opportunity to find his own role and niche.

Would it be helpful to give bochurim a wider range of outlets for their talents and interests? In the Modern Orthodox sector, for example, many young people take positions of responsibility in camps and chesed programs, and this develops their leadership skills and propensity for chesed.

Rabbi Frank: The propensity to do chesed depends largely on how you grew up. If chesed is part of your family culture, there’s a good chance you’ll be involved. Of course, when it comes to child-rearing, there are no guarantees. But role modeling is one of the best things we can do for them.

Regarding working in chesed programs and camps for special-needs children — it’s got to be a life-changing experience for the boys who do it. But there are other options, like yeshivah boys going on SEED programs for their summer break, where they learn with members of the community and give of themselves.

How one chooses to spend his or her summer, and free time in general, is another one of those decisions that can say a lot about him.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: I think a sense of chesed is cultivated all across the frum spectrum. My son is in the Philadelphia Yeshiva, where, despite the emphasis on hasmadah, there is a tremendous culture of chesed. You will never find an empty netilas yadayim cup, because there’s a chinuch that you fill the cup for the next person. If a boy is sick, the others will make sure to bring him food. My son runs a Pirchei group for the children of the rebbeim. Boys can help weaker boys in learning and often learn with younger boys. The range of chesed opportunities may be less broad than in other circles, but it’s certainly there.

But we can learn from the more open circles regarding the range of things we allow our boys to do in their free time — hobbies and so on. We have to recognize that there are more outlets, hobbies that are healthier than just hocking with friends. And they don’t involve technology or other questionable activities. Look, the average “good boy” is learning eight hours a day. What’s he doing the other hours? Many gedolim played instruments or were artistic, for example, without deviating from their hashkafah.

Dr. Pirutinsky: There is a certain price we pay for making Torah a priority. But I see there’s tremendous variety today, even in Lakewood. There are only a few yeshivos that I’d say are super intense. There are tons of baseball leagues and kids who play instruments. It’s not what it looks like from outside — there are Lakewood stereotypes, but today the population is much broader. It’s no longer the self-selected population of a generation or two ago.

How can we help young men prepare for the challenges of marriage?

Rabbi Twerski: I find that in the chassidish community, people tend to be more concerned about what family they’re marrying into. In the Litvish community, there’s more focus on support. But in the end, neither is so important to the success of a marriage. Today, when I evaluate a shidduch, I don’t ask about the learning. I ask about the middos. What does a boy do when he’s angry, when he’s frustrated? How does he handle challenges and adversity?

A boy should understand that he has to be ready to invest in the relationship and focus less on himself and more on his wife. Shortly after my mother died, my siblings and I were all together for a Shabbos, and by the time my sister arrived that afternoon the entire Shabbos was cooked — by my father, who usually left it to my mother but knew how to cook and bake. At the meal I realized one dish was lacking, so I asked my father why he didn’t make it. “I don’t especially care for it,” he said. We were incredulous. For 43 years he ate everything on Shabbos and would stand up and tell my mother, “Thank you, everything was delicious.” We now asked him, “Mommy never knew you didn’t like it?” He shrugged. “Why did she have to know?”

Rabbi Frank: I emphasize to young men that marriage will require work. For years I’ve preached that the most important quality in marriage, and in life overall, is to be a giver. It’s especially important to underscore that to our youth — because the prevailing trend in the secular culture is to place a heavy emphasis on self-care, personal needs, and self-fulfillment. In Judaism, we think differently. For us, self-care is like a pit-stop in life — it’s where we rest and refuel only so that we can go back out there and continue giving to others.

However, because the same focus on self has made people less resilient when facing the challenges of marriage, I’ve added another quality that is essential to making marriage work: to be someone who is willing to roll up his or her sleeves when the work shows up.

Dr. Pirutinsky: I agree. Young marrieds need to recognize that marriage is a process that takes work and time. The ability to see it through goes hand in hand with the ability to tolerate what’s not easy or perfect.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: I believe a sense of achrayus is crucial, although I call it a sweet achrayus. A young man getting married has to move from a “me” world, where you think about what makes you happy, to thinking about the other person’s happiness. I often advise boys when they date to think, “Am I good for her?” in addition to, “Is she good for me?”

I enjoy challenging the boys with this: Let’s say there’s a young husband whose wife is expecting. It’s late at night, and she asks him to get her a cup of water. Half asleep, he shuffles to the kitchen. If I were to tap him on the shoulder and say, “Why are you doing this? She could get it herself,” he might answer, “If I don’t, she’ll kill me.” That’s obviously not what we would want to hear. Some might say, “Because I love her.” And that’s nice but it’s not the best answer. The best response is, “Because I’m her husband, and that’s what husbands do — an achrayus that I take pride in.”

How can we help young men as they make the often-difficult decision to enter the working world?

Rabbi Twerski: In the chassidish world, both the Satmar Rebbe ztz”l and the Bobover Rebbe ztz”l were extremely focused on the importance of earning a living while remaining a Torah Jew. The Satmar Rebbe used to say that the segulah of the mahn is only effective until 8:59 a.m. After 9:00, the segulah is to go to work. The Bobover Rebbe brought in people to teach jewelry-making to his kehillah.

When a young man decides to go out to work, he should be supported for wanting to be an honest provider for his family. Am Yisrael can be compared to a body that has billions of cells, each one with its own function and each one essential. Is any cell less honorable, less important than another? If any of them malfunction, the body is in pain.

When he chooses a career, he should be guided into a career that suits his skill set and that he enjoys. Otherwise, he’ll be miserable. If a fellow has been learning in kollel for 12 years, he might not be a candidate for med school, but he’ll have plenty of other choices.

Dr. Pirutinsky: I see a certain change in the litvish community, in that people are leaving learning at younger ages to go to work. Some see it as failure, others as the next logical choice. I think the ones who have the hardest time with it are men who grew up in more “modern” families yet who chose long-term learning, because they sacrificed more. When they have to go out to work, they’re way behind their siblings who spent the past ten years going to med school or law school, and their parents are saying, “You should have listened to me.” It’s also hard for people whose fathers are still learning, which is a new demographic in Lakewood. But the majority of men understand that you learn until it’s time to move on.

Rabbi Frank: When I was in yeshivah, there was an annual shmuess just for those talmidim who were going to college. The gist of that shmuess was that if you’ve decided that going to college was what was best for your personal avodas Hashem, then it must be treated that way. Do it right. Take it seriously. Over the years, I have been told by talmidim of Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky shlita that whatever they needed to do, he would encourage them to do it the best they can.

What do you see as the biggest challenges when young men decide that work is their best option?

Rabbi Twerski: Young men need to understand that often a first incursion into the work world will not be the success they dreamed about. Yet that trial and error is priceless. They just need to reset and try again until they find what works best for their talents and personality. Failure is part of the process.

Rabbi Frank: Unfortunately, there usually isn’t a gradual transition period from yeshivah life to the work force. Therefore, it can end up being a very abrupt change. In that case, that precipitous drop can see the “yeshivah guy” disappear, replaced by an unrecognizable “working guy.” Everything from sensitivities to wardrobe can change overnight.

Since there are few formal transitional programs built into our system, it is the responsibility of the “working guy” to stay connected to his yeshivah, maintain serious learning and davening schedules, and always remember that his choice to work is not a step down from being an eved Hashem, but a new expression of it.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: Leaving the womb of the yeshivah can be disorienting and destabilizing. I’ve seen guys who never missed a minyan struggling to daven three tefillos a day. Here at Lander, where many of the young men do summer internships, we stay in touch over the summer, and the rebbeim often hear about the experiences of transitioning to the world of the workplace. I know someone who did a four-week internship this summer, and it left him with so much to process. He was suddenly working with non-Jews, being invited to go out for drinks after work, handling issues like shaking hands with women, or asking to leave early for Shabbos.

But if I had to put a finger on the one characteristic of people who achieve success and fulfillment at this age, no matter what they’re doing, it would be relationships. Boys who succeed are boys who have managed to develop real relationships, in yeshivah and at home. They have a sense of being grounded, which is an anchor for them as they proceed into the world of serious decisions and challenges. This summer I learned night seder in Waterbury — for just one hour a night — with a great group of mostly working guys. You could see how precious this time was for them. On Shabbos, with a kehillah of working people, I try to uplift these fellows who have been through a long week, to help them feel the greatness of Torah and to help them reconnect and recharge.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 984)

Oops! We could not locate your form.