Road Map to the Future

Four experts discuss the challenges confronting the young men of our communities

Your son has just finished a year learning in Eretz Yisrael, or perhaps in a beis medrash closer to home, a time when he should be thinking seriously about the direction of his life: future learning, a career, marriage. Yet so many young men have no idea how to go about taking those next steps. How can we encourage today’s young people to be resourceful in preparing them for the successful “launch” to the next phase of life? How can a bochur discover who he is, in addition to his role as a talmid? Certainly, those who wish to continue learning should be encouraged to do so, but what about those who don’t see the beis medrash as their long-term goal — how do they navigate the next few years?

We’ve brought together four experts to discuss the challenges confronting the young men of our communities and how they can create a road map to guide their future

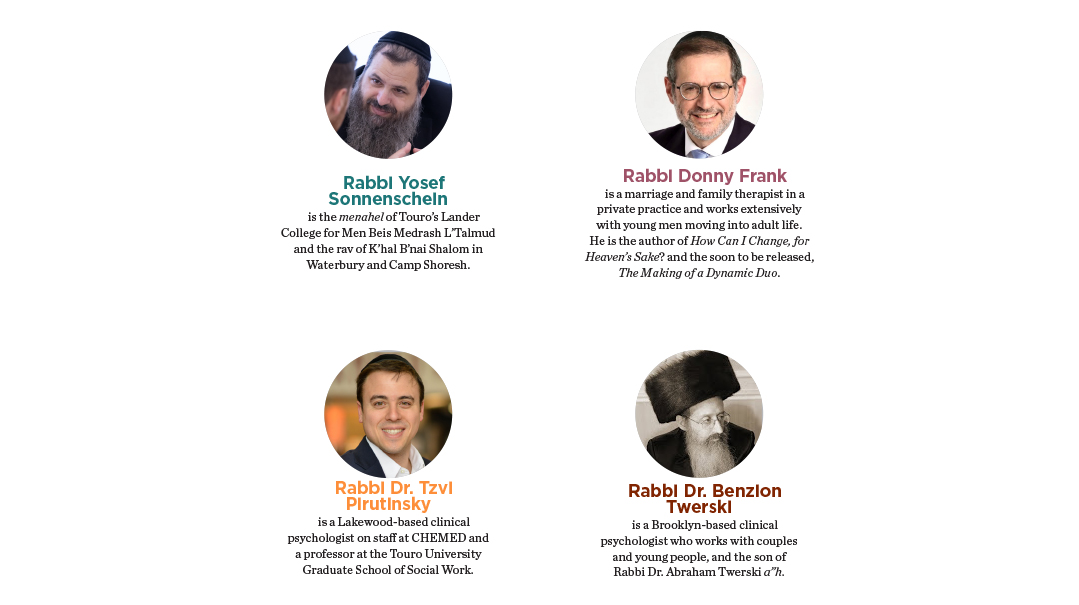

Rabbi Yosef Sonnenschein

is the menahel of Touro’s Lander College for Men Beis Medrash L’Talmud and the rav of K’hal B’nai Shalom in Waterbury and Camp Shoresh.

Rabbi Donny Frank

is a marriage and family therapist in a private practice and works extensively with young men moving into adult life. He is the author of How Can I Change, for Heaven’s Sake? and the soon to be released, The Making of a Dynamic Duo.

Rabbi Dr. Tzvi Pirutinsky

is a Lakewood-based clinical psychologist on staff at CHEMED and a professor at the Touro University Graduate School of Social Work.

Rabbi Dr. Benzion Twerski

is a Brooklyn-based clinical psychologist who works with couples and young people, and the son of Rabbi Dr. Abraham Twerski a”h.

How do we help bochurim navigate the transition from teenager to adult?

Rabbi Twerski: The first step is to encourage boys to be doers, not “possessors.” The level of luxury in our society is a challenge, and we need to teach our children, by example, that wanting something “because everyone else has it” is not a Torah value. Instead, they have to learn not to confuse wants with needs. A mature person is capable of doing without when the situation calls for it.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: I believe that as a community we’re doing a very good job taking care of our children. Where we sometimes fall short is in guiding them to become adults. They’re easily paralyzed by decision-making and have trouble taking on responsibility. This means refraining from merely “paskening” on their questions, rather, taking them through the decision-making process and helping them learn to make their own decisions.

Rabbi Frank: Being away from home and away from parental influences doesn’t mean one will necessarily use that freedom to learn how to make good decisions and take responsibility. Many will simply follow friends and preplanned systems, rather than make personal choices.

When a bochur reaches maturity, goals should start emerging from within, based on personal values, strengths, and weaknesses, and should not be limited to what’s being imposed on him from without.

Parents must be mindful to encourage their young adult children to grow up, and certainly not block that path.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: There are boys who will come with questions about potential shidduchim or life paths and tell me, “My mother wouldn’t permit me to make this type of choice,” or, “My father wouldn’t allow it.” I’m tempted to say, “If you’re in shidduchim, that means they think you are mature enough to be married… shouldn’t they allow you a voice in your decision making?” Instead, parents should be helping their children learn how to weigh the pros and cons, listen to their own gut feelings and enabling them to make their own choices. Once parents frame the decision-making process, they should be telling their children, “We trust you to make your decision.” We can help our children and talmidim make choices not by deciding for them, but by clarifying the issues and walking them through the consequences.

Rabbi Frank: I attended Yeshivas Ner Yisroel, and Rabbi Yaakov Weinberg ztz”l would talk a lot about personal responsibility. For example, an askan called him about a particular community challenge to find out what he should do. Before answering, Rav Weinberg asked him, “Well, what do you think?” When the askan admitted to not having really thought it through, Rav Weinberg asked him to call back the next day with his thoughts, at which time he’d share his.

Dr. Pirutinsky: We have to teach our children to learn to tolerate negative emotions without jumping in to fix things for them. Let them make bad decisions! They have to learn that failure is always a possibility and they have to be ready to tolerate it.

This issue isn’t limited to the frum community. It has been a trend in the US over the past 100 years that adolescence is being extended longer and longer — in fact, the frum community generally lags behind the secular world where such trends are concerned. As a society, our tolerance for problems of any sort has gone way down. We expect perfection, and parents are quick to step in if something seems to deviate from that.

Rabbi Sonnenschein: A mother once called me to say that her son had been suspended from camp because he’d been caught drinking the very first week. She asked me to intervene on his behalf. I said to her, “Are you sure you want me to intervene? Is that the lesson you want him to learn, that he doesn’t have to respect the rules because someone will bail him out? Will that teach him achrayus?”

That said, a parent shouldn’t respond to a situation like this by telling the child, “Well, good! Now you’ll learn your lesson!” They should be compassionate and understanding that the path of growing up is littered with poor decisions, and that misjudgments are part of the process.

Dr. Pirutinsky: Yes, a parent can say instead, “I’m sorry, and I know this is hard, but you broke a rule and these are the consequences.”

Oops! We could not locate your form.