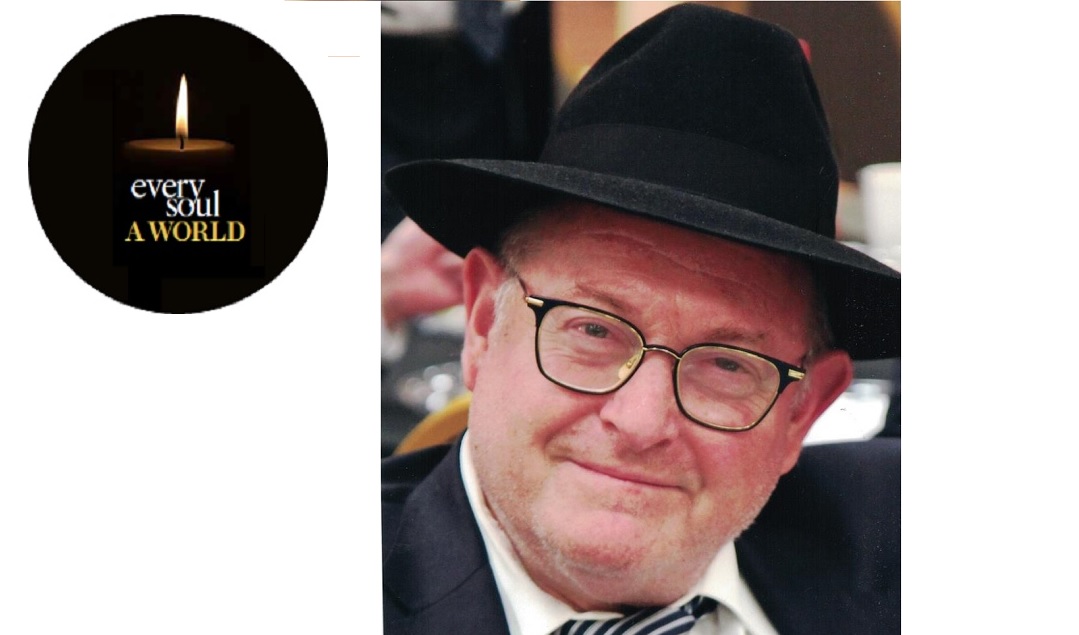

Reb Ezra Binyamin Bloch

In my father-in-law’s world, no time was inconvenient, no time too early or too late, when it came to serving the Creator

T

he location isn’t what matters — yet the scene was always the same: An empty beis medrash late at night, perhaps the Satmar shtibel on Northumberland Street, or maybe Chodosh next door, and one lone, lingering figure inside, the rest having long ago retired for the appeal of their homes. If you listened closely you could make out the occasional rustle of his slow, deliberate movements, or the gentle rise and fall of his singsong voice against the rhythm of what was likely another Manchester rainfall outside.

But not the silence, nor the weather outside, and certainly not the hour, could deter Reb Ezra Bloch’s resolve when it came to avodas Hashem. Because in my father-in-law’s world, no time was inconvenient, no time too early or too late, when it came to serving the Creator. In fact, time wasn’t even a factor in his world; all that mattered was Torah and tefillah and a deep, deep she’ifah to touch whatever holiness he could, whenever he could. His absence at home often spanned hours, but you just knew: if Papa wasn’t around, there weren’t many options; he was either in the beis medrash around the block, or in the other beis medrash around the other block. In Manchester, there was no shortage of addresses for Reb Ezra’s thirsting soul.

That was the thing with Reb Ezra. You always got the feeling — watching him, speaking to him — that he was stretching, that there was somewhere he was trying to get to, but could never quite reach. Reb Ezra’s Shabbos table was a sacred space, but not merely for the good food and lively family atmosphere; for him, the taste of Olam Haba meant so much more than a chance for steaming soup. It was a weekly occurrence for the Blochs: soup would be served and inevitably my father-in-law, with his beautiful, melodious voice, would launch into a heartfelt rendition of Menuchah V’simchah, or Kah Ribon, or both, as though his soup would stay hot forever and Shabbos was here to last all week.

Neiros Chanukah was a similar affair. The kids would urge him along. “Papa, we need the room, our friends are coming, we’re having a party,” they’d say, hopeful that this time their father would accommodate. But Reb Ezra didn’t understand the problem. “Let them come, shoyn,” was his rejoinder. Why would his singing disturb anyone? No way was he going to pass on saying his slow, earnest vehi noam the full seven times. It wasn’t an option.

Choosing arba minim each year was one of his annual highlights. Often, he’d be so determined to do the mitzvah right that he’d bring home several esrogim, much more than the family could afford. He’d choose the right one later, he’d assure his family, and return the rest. But later Reb Ezra was more undecided than ever, and by the time Succos came in, he often had enough esrogim for each of his three sons and sometimes even another one to spare. That’s how it came to be, one year, that a little boy from Satmar got to boast his own beautiful esrog. Whether the boy or my father-in-law was happier, you couldn’t tell.

Reb Ezra Bloch’s trajectory didn’t begin in Satmar. Or in Manchester, for that matter. In fact, growing up in his Zurich hometown, in a family that belonged to the IRG yekkish kehillah, young Ezra Bloch had little to do with chassidim. From there it was Lucerne, then Gateshead, then the Mir. Twenty-seven years ago, if you had asked his then-kallah, Rivka Chana Chissick of London, she would have laughed at the notion of her chassan one day donning a shtreimel — not out of contempt but out of amusement at the incongruity.

But when it came to it, it made perfect sense. In the spring of 1996, after spending the first years of their married life in Eretz Yisrael and then London, the couple decided to settle in Manchester. There, the lure of the Satmar beis medrash just a few minutes from their home was too great for Reb Ezra’s essentially chassidishe soul, which longed for connection and meaning. First it was the gartel, then the beketshe. Naturally, the rest followed. Looking at him in 2020, seeing his conduct in shul, at the mikveh, you couldn’t imagine Reb Ezra any other way.

Twenty years ago, when the activist who ran the boys’ after-school woodwork program was looking for the right person to teach his workshops, he had three criteria: that he be good with his hands, good with children, and that he be a yerei Shamayim. In Reb Ezra, he found all three. Since then, some 3,000 children, from all ends of the religious spectrum, have crossed over that threshold, over the course of time learning more about middos tovos, generosity of spirit, and yiras Shamayim than about the workings of wood — though from the masterpieces the boys would bring home, they learned about that, too. At woodwork, Reb Ezra would often treat his boys, a pound here, a pound there, “go buy yourself something nice,” not for any reason, just because.

Because Reb Ezra loved to give.

Because giving was Reb Ezra’s lifeline.

When they would host his mother-in-law for Shabbos, one bouquet wouldn’t suffice. There needed to be two, one for his wife, another for Bubba. At the mikveh shop on Fridays, they used to joke that a separate checkout was needed for Reb Ezra; he’d put this on the counter, that on the counter, another salad, more arbes, until the pile teetered and Reb Ezra could feel assured there’d be ample supply to go around. Not because he doubted his wife’s ability to cook up her weekly Shabbos storm, not at all, but because of his deep penchant for plenty.

Erev Yom Tov, his only concerns were for others: “Make sure your wife has something new for the chag,” he’d quietly tell his son. His grandkids, his nieces and nephews, they all knew — if Papa was around, it meant not just one nosh to share, but one for each kid, and not just one for each, but the biggest package the store carried.

Sometimes, a Yid would come around on Fridays and ask for money. Barely a man of means himself, if it meant borrowing money to have what to give, that’s what Reb Ezra did. “Surely we’re not mechuyav to give him,” his wife would reason, but Reb Ezra wouldn’t listen.

That was Reb Ezra. He loved his fellow man — so much, that you never heard a word of lashon hara, or any hint of scorn, cross his lips.

His children meant the world to him, too. When he’d sing and dance with them, it was all-nachas, all-joy — and often a gift, too, while he was at it.

But, oh, he struggled too. Not the kind of regular, everyday frustrations of the ordinary person. Reb Ezra’s pain was simply that of a neshamah searching for emes in a world of sheker, the grief of a nefesh longing for infinity in a world so constrained by desire, time, space. Reb Ezra wanted nothing more than to be able to spend his days immersed in tefillah and avodas Hashem and was frustrated by the interruptions of mundane life to his slower, more careful pace.

When the 48-year-old Reb Ezra collapsed suddenly, on the fourth day of Chanukah, from his inability to breathe through his swollen tonsils, and stayed unconscious throughout Chanukah, I said to my husband, “Imagine Papa’s horror when he wakes up and realizes what he missed.” I was referring, of course, to my father-in-law’s special kinship with the Yom Tov of Chanukah, the Yom Tov of flames, of neshamah. We didn’t dream then that Reb Ezra, our beloved father and father-in-law, would also miss Purim. Neither did we dream of the impact of the deadly virus rapidly making its way though the world and about to sweep the country.

A couple of days prior, a choshuve talmid chacham walked into Chodosh looking for someone to learn with. It was late, but Reb Ezra was still there, learning, davening. They talked of beginning a chavrusashaft.

That first night, it lasted a couple of hours.

The second night, Reb Ezra got sick. I won’t make it tonight, he wrote in a text message, not unbegrudgingly. I’m not feeling well. Be”H I will get in touch as soon as I’m better.

But Reb Ezra didn’t get better.

That message was to become Reb Ezra’s last message, his parting gift.

For weeks until the virus hit, Reb Ezra balanced between life and death. But the oilam — all those who knew Reb Ezra and loved him — came battle-ready. With the amount of Tehillim being said, it was hard to envision another outcome. He was still so young; there was still so much, we knew, that Reb Ezra wanted to accomplish. We held our breaths.

In the end, it was corona that took him. How immobile, unconscious Reb Ezra caught the virus will forever remain a mystery. But in what felt like a hug from the One Above, it was clear that Reb Ezra went peacefully, bli tzaar. It was in the late afternoon on the first day of Pesach, on Erev Shabbos Chol Hamoed, on the Erev of Shabbos Shir Hashirim, the song that speaks of longing.

If Reb Ezra could have chosen the time for his levayah, no doubt he would have said Erev Shabbos. Erev Shabbos, preparation for peace.

Reb Ezra’s parting comes with no small amount of pain and heartache to all those who knew him — though surely, no doubt, he is in the best possible place. Surely, Reb Ezra, who hovered between the two worlds all his life, whose whole raison d’être was one long desperate striving for connection, has at last found true menuchah v’simchah. Surely, he can’t be anywhere else other than in the heichal ha’elyon, relishing the emes of the World of Truth.

There, we are sure, he has finally found what he was looking for.

And that, along with Reb Ezra’s beautiful, pure legacy, will be our nechamah.

VIEW/DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION

Oops! We could not locate your form.