Rallying Cry

For young Jews of the 1960s and 1970s, the cry “Let my people go” didn’t refer only to Pharaoh and Mitzrayim. This was also the battle cry of the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry.

O

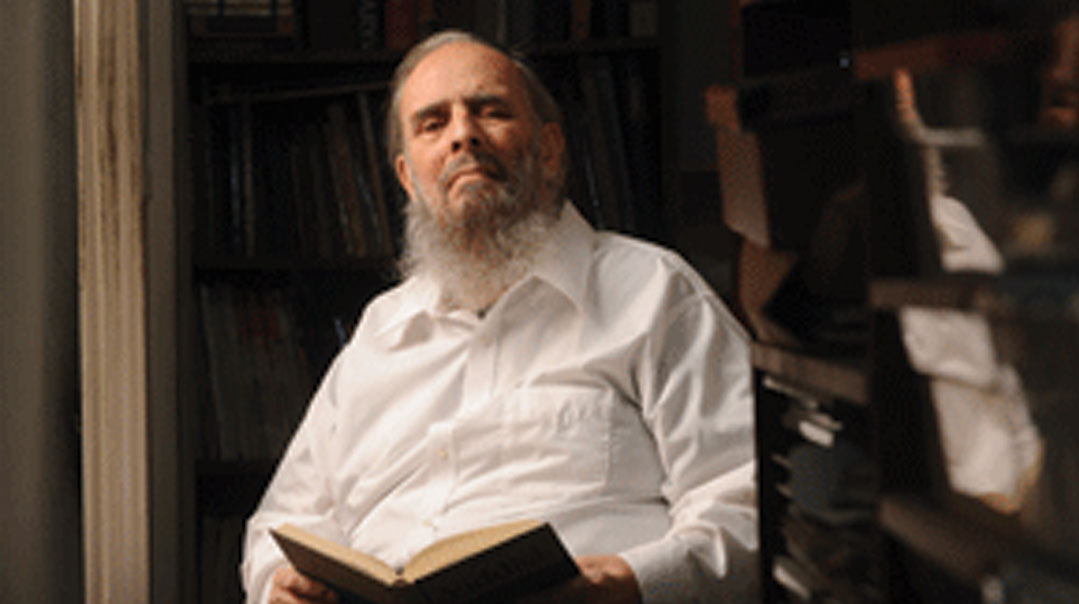

ne could say that Dr. Birnbaum got his first taste literally of the problem of being a Jew in a totalitarian country while he was still a young child. His family was living in Germany in 1933 the year when Hitler rose to power. His father Solomon Birnbaum was brutally attacked on the street by thugs. Even six-year-old Jacob didn’t escape. “I was attacked inside our garden ” he remembers. ”A group of boys hopped the fence and stuffed dirt into my mouth — it was terrifying. I resisted vigorously and ran away. Curiously my first reaction wasn’t resentment but a sense that they were Nazis and what else could one expect?”

Solomon Birnbaum moved his family to England in the late 1930s before war broke out. While the family was in London the young Jacob was sent to a Jewish school started by Rabbi Avigdor Schonfeld the father of Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld who organized the Kindertransports out of Germany and Austria.

Jacob Birnbaum began his own career as an activist after the war when he was just 19. Small groups of Holocaust survivors many of them young people were arriving in England. Penniless and without friends or families these young people often had nowhere to sleep except the floor of a shul. Birnbaum fought on their behalf attempting to convince the British authorities to provide these young survivors with a place to live and food to eat.

The challenges of working with these battered survivors brought forth his skills as a leader: “Some of them had fought with the partisans and they were wild! I still remember one — his name was Yosef Yehoshua — who had a scarred face. The other fellows rushed over to me exclaiming ‘Yosef Yehoshua has a whole suitcase full of knives!’ Well I was big and he was small but he was strong. I told him very quietly and politely ‘Yosef Yehoshua give me the knives and I’ll look after them. I’ll show you where I keep them and if you need them I’ll give you the key.’ ”

Birnbaum smiles. “That fellow eventually became a gabbai of a shul where he blew shofar on the Yamim Noraim and is a respected balabos!”

With time the survivors settled into their new homes. But this didn’t mean that Birnbaum’s career as a communal activist had come to an end — it just changed its focus. Following the establishment of the State of Israel and the beginnings of unrest in Algeria conditions in North Africa for the Jews had become highly precarious. A small group of young men were therefore brought from Morocco to a yeshivah established by Rabbi Shamai Zahn in Sunderland UK and Birnbaum found himself helping out. He also contacted the son of the head of the Jewish Committee of France and proposed sending student volunteers to Morocco to help send young people to England Switzerland and elsewhere. To his surprise he easily amassed a group of volunteers and set off for Morocco with one of his Moroccan students as a guide.

Birnbaum traveled to all the major cities of Morocco visiting all the schools. “You can see the level of Yiddishkeit in the schools” he says. “The largest was Otzar HaTorah in Casablanca. I’d speak to the parents and encourage them to send their children on for further education.”

It was a great adventure and the end result of Birnbaum’s meanderings in Morocco was that a lot of young people were helped to emigrate to pursue a higher education and given a chance at a better life. After wrapping up his Morocco project and finishing yeshivah studies at Eitz Hayim and evening college (where he “read” modern European history) Birnbaum took a job in 1957 as director of the Jewish Community Council of Manchester and Salford. He stayed on the job for two years but found himself disappointed with the level of the Jewish community. He began meeting secretly with young people discussing how to re-inspire Jews in an uninspired generation.

Then in the early 1960s he left for Eretz Yisrael. While there he become friendly with several Americans among them a 20-year-old rabbinical student from Yeshiva University named Shlomo Riskin and began to think the US might prove more fertile ground for the sort of revival movement of which he dreamed.

Soviet Jewry Calling

I

t was Shlomo Riskin who picked him up from the airport when he flew to New York in 1963. “I thought I could publicize the problems of North African Jews and explore Jewish renewal on campus, and Yeshiva University seemed a good base for this work,” Birnbaum explains. “But once I got there, it soon became clear it was time to take action with respect to Soviet Jewry.”

Why Soviet Jewry? And why did Birnbaum have this epiphany while visiting the United States?

In the Cold War decades following World War II, the free world considered the USSR its greatest threat. Huge, powerful, and unquestionably evil — USSR dictator Joseph Stalin killed more people than Hitler during his reign of terror, and his successors continued to enforce Stalin’s policies of repression and coercion, as well as a corrupt and dysfunctional economic system — the USSR was the bully no one dared to challenge. Not only did the Soviets possess nuclear weapons and beat the US into outer space (although not to the moon), but they seemed bent on pulling underdeveloped countries into their orbit.

Three million Jews lived in the USSR after World War II, a quarter of the world’s Jewish population. They had been, according to Yossi Klein HaLevi in Azure (Spring 2004), “singled out for a state-sponsored experiment in enforced amnesia.”

Klein HaLevi continues, “Where other religions were permitted to train clergy in their own seminaries, and other ethnic groups were granted national theaters in their own language, Jews were denied almost all expression of collective identity … Though 450 synagogues had survived the Stalin era, by 1963, all but 96 had been shut down by the regime. Jews were accused of undermining the Soviet economy, and some were executed after public ‘economic trials.’ KGB spies were planted in synagogues, and most worshippers were too terrified even to speak with Jewish tourists from the West; those few who did would only allow themselves to brush up against a visitor and whisper urgently, ‘They don’t let us live,’ or ‘Why are American Jews silent?’

Klein HaLevi points out that there were no historical precedents for creating a campaign against an anti-Semitic regime. Furthermore, postwar American Jewry still felt “demoralized by assimilation and shamed by the failure to rescue Jews in the Holocaust.”

However, Jacob Birnbaum, believing that the USSR was not impervious to political pressure from the West, was encouraged by what he saw during his visit to the US. “The US was the only place where you saw any response to occasional reports of persecution. It was also the only country powerful enough to take on the USSR. I therefore said to myself, ‘This is the time! This is the place!’$$separate quotes$$”

The first person he contacted was Morris Brafman, who had organized a small group of activists in Mill Basin, Brooklyn, called the American League for Russian Jews. After attending a few of their meetings, Birnbaum said to Brafman, “Morris, if you raise me some money, I could get things going and direct this for you in the student community.”

The money never materialized. Birnbaum therefore tried to raise money on his own, running letter campaigns and searching out contacts. But he encountered stiff resistance from both secular and religious quarters. “They all thought the old shtadlanus tactics [quiet diplomacy] were the only way to go. In earlier times in Europe, the Jews would send a rich or influential Jew to the local king or count to plead their cause, and for a price the ruler would call off the dogs.”

Birnbaum believed that quiet diplomacy wouldn’t work in totalitarian regimes where entire societies live in fear. “It didn’t work in Germany,” he points out. “The Jews had lived for a thousand years in Germany, often on friendly terms with their gentile neighbors. But once Hitler commanded them, they abandoned the Jews.”

Instead, what was needed were masses of people willing to publicly “shrei gevalt” and American Jews, who were living in a democratic society, had the freedom to speak out and put pressure on elected officials. Assessing that the single largest group of Jewishly committed young people was to be found in the Yeshiva University dormitories, Birnbaum began knocking on the doors of student apartments in early 1964. “They used to look at me like I was crazy!” Birnbaum chuckles. “They saw the Vandyke beard and heard my accent, and their reaction was, ‘Who is this man? Nobody told us about this before.’$$separate quotes$$” Often people told Birnbaum in no uncertain terms — sometimes with a fist in the face — that raising a ruckus risked putting our Jewish brethren in deeper danger.

Undeterred, Birnbaum managed to convince Yavneh, the national religious student organization, to create a committee for Soviet Jewry in 1964. By April he decided to go national, writing up the manifesto “College Students Struggle for Soviet Jewry,” and organizing a meeting at Columbia University. The manifesto described the Catch-22 situation of Soviet Jewry in clear terms, stating it was evident that the USSR was engaged in “a concerted effort at spiritual and cultural strangulation, very often shot through with vicious anti-Semitism. The net result is that masses of Jews are living in an increasingly ambiguous position, neither assimilating nor living self-respecting lives, nor yet being able to emigrate.… We who condemn silence and inaction during the Nazi Holocaust, dare we keep silent now?”

Save Soviet Jewry!

T

he Columbia meeting proved an emotional sparkplug; the students wanted action. When Birnbaum mentioned that the socialist holiday May Day was four days away, enthused students called for a protest rally on that day at the Soviet UN Mission. Despite the challenges of pulling together a rally in just four days, over a thousand people showed up, many of them Birnbaum’s core YU supporters. “I got there, and to my surprise, who was there? Rav Soloveitchik’s son-in-law, Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein!” Birnbaum says, still marveling. “Nobody had asked him to come — he just showed up, and stayed for two hours!” Many influential community leaders were impressed by the rally, which received page-two coverage from the New York Times. Just ten days later Birnbaum set up the first steering committee of the SSSJ (Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry), launching it with the slogan “Save Soviet Jewry” (soon to become the famous “Let My People Go!”).

Part of Birnbaum’s organizational genius lay in recognizing young leadership talent and cultivating it. The list of those who cut their leadership teeth on SSSJ activism reads like a Who’s Who of American Jewish leadership in subsequent decades: Shlomo Riskin (“he had boundless energy, he would jump off the floor with enthusiasm”), Yitzchak Greenberg, Dennis Prager (who served as national spokesperson), Joseph Telushkin, Malcolm Hoenlein (who went on to head the Greater New York Conference on Soviet Jewry and currently serves as executive vice chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations). Meir Kahane, then a kollel student and Jewish Press contributor , was personally converted by Birnbaum into an enthusiastic supporter. They quickly parted ways, however, because Kahane was impatient for results and began urging action of a more violent nature. (“I pointed out that if we exploded a bomb at the Soviet UN Mission, we might gain some short-lived notoriety, but the movement would be shattered in its infancy,” Birnbaum later wrote.)

Birnbaum also had a talent for stirring Jewish souls by weaving powerful Biblical imagery and the redemptive themes of Pesach and Chanukah into his campaigns. His early supporters wore buttons with an image of a blue shofar on a white background and the words “Save Soviet Jewry,” as a “call” to action. The two “Jericho” marches of 1965, accompanied by shofar blasts in front of the walls of Soviet diplomatic buildings in New York and Washington DC, were “a good symbolic manifestation of our early campaign to breach the Iron Curtain.” (There was another highlight at the New York event: In response to Birnbaum’s request, Shlomo Carlebach created and performed the now-famous solidarity anthem Am Yisrael Chai.) The year 1965 also saw the Freedom Lights Menorah March through Central Park, which included a huge menorah constructed of large pipes that took Birnbaum and a few well-muscled supporters most of the night to shape. The following Pesach, his “Geulah/Redemption March” attracted 12,000 people, and Holocaust survivor Morris Katz painted a large “redemption” mural for the occasion.

The late 1960s and early 1970s were an auspicious time for launching and sustaining a student-led protest movement. Anti-war student protests on college campuses were the fashion, among other political and ethnic causes. For unaffiliated Jews, the Soviet Jewry issue provided a crucial opportunity to affirm their Jewish identities. Birnbaum says he received many calls from parents. Some thanked him for deflecting their children away from the more dangerous and non-Jewish civil rights movement. Others cried hysterically, “I saw my kid on TV last night demonstrating. How dare you put Jewish youth in danger?” Birnbaum’s SSSJ, however, was always careful to hold orderly, nonviolent demonstrations, which maintained the organization’s reputation for seriousness and decorum and allowed both participants and the press to feel comfortable attending.

In 1970, a group of about 40 Soviet Jewish resistance members were accused of plotting to hijack an airplane to Sweden and put on trial. Two were sentenced to death and others to lengthy prison sentences. The resulting public outcry roused the mainstream Jewish community leadership to finally form, in 1971, two full-time organizations devoted to promoting the cause of Soviet Jewry: the National Conference on Soviet Jewry and the Greater NY Conference on Soviet Jewry. “After seven years they did this! For seven years we at SSSJ were the only ones, working day and night with no resources!” Birnbaum says, still incredulous.

With his usual farsightedness, he had long argued that the seemingly monolithic USSR was not invulnerable to foreign pressure, especially in the soft Achilles’ heel of their stagnating economy. “They badly needed international capital, trade, and technology, and the US was the home of that,” he explains. He worked closely with Senator Henry Jackson’s office in the early 1970s to implement economic leverage against the Kremlin, testifying in Congress, until the Jackson-Vanik Act, which denied most-favored nation trade status to countries restricting emigration, was signed into law in January 1975. “It cut a deal with the Russians,” Birnbaum explains. “We’ll give you favorable trade conditions, you’ll let the Jews go!”

A Lifetime of Caring

B

y the late 1980s, Jews had been granted permission to emigrate and began doing so in large waves. As Birnbaum saw our people increasingly allowed to leave, he realized more than ever that these spiritually deprived Jews were badly in need of education and inspiration. His new SSSJ slogan became “Let My People Know,” and he now turned to Jewish educational initiatives in the USSR, Israel, and the United States. In the 1990s he also advocated for Jews in Uzbekistan, organizing an Internet letter campaign to free an imprisoned Bucharian Jew named David Fattakhov.

Birnbaum’s tireless activities on behalf of others left him little time for a personal life. But one summer evening in 1971 while handling an emergency — he needed to reproduce photographs of Soviet prisoners for the following morning, and asked the students for a referral — he met a young amateur photographer, Freda Bluestone, who was willing to do the all-night job. “There were no Kinko’s copy stores back then,” he grins. “I bought her chocolates in gratitude.” The professional collaboration became personal, and they married that fall. In the ensuing 40 years, Freda has remained his most loyal supporter and full-time helpmate. Although they have no children, they happily play devoted uncle and aunt to their siblings’ many children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

Birnbaum’s many years of advocacy brought him into first-name relationships with scores of powerful people. He’s been friendly with almost every mayor of New York since 1964, particularly Abe Beame, John Lindsay, and Ed Koch, as well as many US Congressmen. He also met many of the gedolim and influential rabbis of the past 50 years; he was in contact with, Rav Soloveitchik, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rav Moshe Feinstein, Rav Hutner, the Bobover Rebbe, and many more. He retains a deep admiration for Rabbi Moshe Sherer, “a great man who considered himself a disciple of my grandfather.”

My conversation with Jacob Birnbaum has spilled over the arranged hour, and he looks visibly tired, so we agree to wrap up. Freda needs to run an errand, and offers to accompany me back to the train. As we short-cut between raindrops up a flight of stairs and through a park, I get the chance to ask a few more of the questions that linger, such as: How did the couple survive financially all these years, while devoting themselves so completely to Jewish causes?

“I worked as a programmer,” Freda replied. “And we’re savers, not spenders. We rarely ate out, and we both lived through difficult times in our youth.”

But what she really wants us to understand is how profoundly her husband is a gutte neshamah, a person single-mindedly focused on improving others’ lives. “Other people who get involved with big movements are often in it for their egos, or to obtain power or money,” she says. “But my husband is completely incorruptible — he’s very pure.”

She recounts a Birnbaum family story in which the little Yankev was offered the special treat of a piece of candy. Before accepting it, he asked, “And Chavi too?” He wanted to make sure the pleasure he was about to enjoy would be available to his little sister as well.

Those of us raised in free countries don’t consider freedom a special treat. But people denied basic human rights — the ability to come and go freely, to practice their religion, to express themselves without fear — imagine these yearned-for freedoms as sweeter than any candy. Jacob Birnbaum has the enormous zchus of having spent a lifetime making sure that all Jews, not only those in his community, would be able to enjoy the riches of a free and spiritually rich Jewish life.

The Making of an Activist

A

mong the many precious documents in Dr. Birnbaum’s archive is an embossed beige card embellished in gold. Dated October 1886, it announces the Vienna betrothal of Rosa Korngut to Nathan Birnbaum, Reb Yankev’s illustrious grandfather. “My great-grandfather was from Ropschitz, a chassidic center in Galicia. But by the 1880s Jews had begun moving out of the shtetlach to the large cities.”

In 1882, while still a student, Nathan Birnbaum and two friends formed Europe’s very first Zionist organization, dubbed “Kadimah” (a double entendre indicating movement not only forward, but eastward to Palestine). “My grandfather was the linchpin of the movement. He was the one who coined the term ‘Zionism,’ and set up its first journal, called Selbst-Emancipzion. It wasn’t until 14 years later that Herzl produced Der Judenstadt.”

Nathan Birnbaum also developed an interest in Yiddish literature, organizing the first Yiddish language conference in Czernowitz in 1908. Realizing that Yiddish literature drew its vitality from authentic Judaism, he delved into his spiritual roots, befriending one of the Polish chassidim who came to Vienna during World War I. In the end, Nathan recanted his secular worldview and became a fully observant baal teshuvah, causing no small sensation. “His friends were furious!” Birnbaum chortles. “Everyone was moving away from religion, and here he was moving back!” Switching focus from physical to spiritual ascent, Nathan founded a society he called “Olim,” whose goal was to create a worldwide Jewish spiritual revival. He’d been the first secretary for the World Zionist Organization, but after changing allegiances he later served as secretary-general for the newly founded Agudath Israel.

Nathan’s son Solomon Asher, who inherited his father’s love of Yiddish, became an expert on Yiddish and other Jewish languages, creating the first scientific Yiddish grammar and serving as a professor at the University of Hamburg. “My father was a scholar’s scholar,” Birnbaum claims. “He could grasp the entire structure of a language in a weekend, and he knew everything about early Hebrew lettering. When the Dead Sea Scrolls were found, he was called on to help date them, and despite controversy, his assessments were later confirmed by carbon dating.”

The rise of Nazism in the 1930s prompted Solomon to take his family to England, but he found it impossible to make a living. “We moved six times in two years,” Birnbaum remembers sadly. “It was awful. In those days nobody knew or understood my father’s research, and there was no department of Judaic Studies to hire him.”

One day, a stranger knocked on their kitchen door with a copy of his father’s scientific grammar in hand. “I’m looking for Professor Solomon Birnbaum,” said the man, who was Professor Norman Jopson, a non-Jewish, world-class linguist. Jopson would eventually create two lectureships at London University for Birnbaum’s father, one in Yiddish/Slavonic and the other in Oriental languages. Once the war began, however, Solomon was tapped to work for the Uncommon Languages Department of the British National Censorship in Liverpool. “He read all the terrible letters coming in from the Jews,” Birnbaum says. “He was of course forbidden to speak about his work in detail, but we knew what was happening. Day and night we listened to radio broadcasts of Hitler screaming his curses and threats against the Jews.”

While Solomon Birnbaum was a very academic, non-activist type, when he heard that some Jews in Bergen-Belsen had been spared because they had papers to go elsewhere, he began writing to various governments, asking them to proclaim foreign Jews as their citizens and help them to leave Europe.

After the war, Jacob Birnbaum became involved with social activism for the first time when he helped young survivors who had recently arrived in England.

“About half were concentration camp survivors, and half were Polish Jews who had fled to the Soviet Union and were allowed to leave with their Polish passports,” Birnbaum recalls, adding that those who had fled the Soviet Union gave him his first detailed awareness of life under Communism, impressions that would later help propel him into a life-long career as a communal activist.

Jacob Birnbaum’s achievements where publicly acknowledged in 2006, on his 80th birthday, when the US Congress passed a resolution commemorating his 60 years of vital, game-changing contributions to not only the Jewish community, but to human rights for all.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 390)

Oops! We could not locate your form.