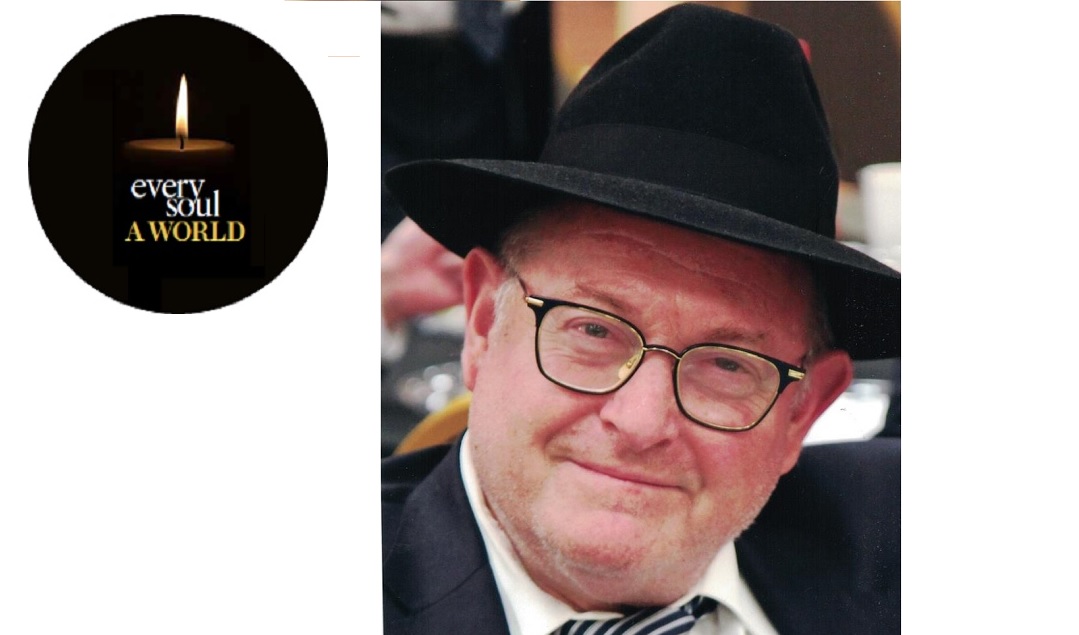

Rabbi Moshe Homnick

| May 27, 2020Besides being one of the top learners in the yeshivah, my father evinced a joyous personality that made people want to be around him

S

everal years ago in this publication, my friend Eytan Kobre penned a poignant feature about the Tishah B’Av shiur given for six decades in Camp Morris by my late father, Rabbi Moshe Homnick. The word “shiur” and Tishah B’Av rarely share a sentence, but when they do, one imagines a one-hour talk covering some lesser-known facet of the Beis Hamikdash and concluding with a reminder to avoid the baseless hatred that brought that holy structure down.

My father’s shiur was a marathon, beginning with 90 minutes or so in the evening, after Eichah. He resumed in the morning after Kinos, then went on all day with a pause for Minchah. All told, he put in eight or more hours covering the sad sections of Gemara that may be studied as we mourn. He began this project as a single student in his early twenties and continued into his eighties. He took off in 1967 for one year, because Israel had just recaptured the Kosel and he thought he should experience the Churban at its source, the better to be its spokesman in subsequent years.

This was his one day a year to reach yeshivah bochurim directly, so he tried to work into his presentation some messages he thought those students needed to hear. For example, the Gemara tells of the wealthy heiress who sent her servant to the market to buy wheat on the day the storehouses of grain had been burned down. He came back empty-handed, saying wheat was sold out and only barley was available. She sent him back for barley but by that time there was no barley either, and she wound up with nothing to eat, despite her vast holdings.

My father would quote Rabbi Henkin ztz”l, saying that the confirmed bachelors follow this life pattern. By the time they are willing to settle for what they can get, they can no longer get that, either.

By sharing life wisdom of this variety, my father was able to effect attitude adjustments even in his one-day-a-year access. The more troubled personalities had the option to become paying customers of his counseling practice, where they could benefit from his advice at any time.

Although that was his livelihood and he could not afford to give away the goods for free, he was constantly being pressed by people facing difficult struggles and often offered lifesaving assistance without charging. Thus, as children growing up, we knew that every walk home from shul on Shabbos would involve someone accompanying us home and buzzing in his ear. The same was true every time we tried to eat out quietly at a restaurant.

My father started school in RJJ but ended up in Mesivta Rabbi Chaim Berlin at age 15 in 1946 via a free summer in Camp Morris arranged by his uncle, Sam Gottlieb. Uncle Sam was one of the founders of Lakewood Yeshiva and was friends with Morris Meltzer, the philanthropist who had given the camp a lot of money… and his name. My father went because the price was right, but he fell in love with the students and never looked back.

Rabbi Avigdor Miller had just been hired as Mashgiach and my father was the first student he tested for admission. My father was so impressive that the yeshivah accepted him directly into the highest shiur, which already included two 15-year-old geniuses, (Rav) Gershon Wiesenfeld and (Rav) Aharon Lichtenstein. My father had the advantage that the rosh yeshivah, Rav Yitzchak Hutner, had been a principal at RJJ when my father’s mother presided over the Sisterhood.

Rav Hutner only referred to that once in their relationship, when he said, “I detect in you a quality that I saw in your mother.” Although his rebbi (as my father always called him) did not elaborate or specify, my father felt endorsed by that on many levels: the care and interest in the student rooted in a respect for his family.

My father’s first two roommates in Chaim Berlin were two of our great gedolim today, Rav Dovid Cohen and Rav Yonason David. After my father started going to college at night, they asked him if he thought they should go, too. He told them not to do anything without asking the rosh yeshivah. When they posed the question to Rav Hutner, he said to them, “If I let you two go to college, they will put me in the seventh level of Gehinnom and never let me out!”

Besides being one of the top learners in the yeshivah, my father evinced a joyous personality that made people want to be around him. Reb Michael Raitzik tells me that one evening Rav Hutner called the payphone outside the beis medrash and asked for my father. He told my father to pull a group of guys together and drive down to a catering hall in Williamsburg where a chassan from the yeshivah was experiencing a decidedly unlively wedding. My father enlisted another bochur who also owned a car and they arrived at the wedding with two carloads of bochurim. To trigger extra excitement, they actually danced their way in from the door and brought a new life into the party.

This charisma extended to his non-Jewish work associates as well. When I was about six, circa 1964, my father began working for the City of New York in a civil service position. He ran a high school equivalency for teenagers and young adults who had done prison time. He used that opportunity to give his mother, Jenny Homnick (1900–1975, born in New York City), then in her sixties, the chance to finish high school. She’d had to leave before graduation when her mother passed away and her father needed help in the store. Now she sat surrounded by street toughs who adored her as she tirelessly helped them with their schoolwork.

His supervisor at that time was an African-American, Doctor Abrams, and my father would sit for hours after work schmoozing with him about life. Once Abrams asked: “There are very few things that achieve universal agreement. One of those seems to be that Jews are no good. How would you explain that?” My father responded by reminding Abrams of his most awful childhood trauma, the day Abrams’s mother bought him a new suit. When he went outside, the other kids were jealous and kicked up dirty water from puddles onto his suit. “The way those boys looked at you is the way the world looks at the Jew.”

As children growing up (I am the oldest of nine), we benefited from that boisterous spirit. Our Shabbos and Yom Tov tables were very leibedig. My father’s father had a tradition that he was the twelfth consecutive generation of chazzanim, so although he made a nice living as a pharmacist, he made sure to keep his position as baal Mussaf for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur at a shul next to Prospect Park. My father let his brother continue the chazzan chain going in the world, but at home we sang all the family tunes with gusto. He spiced up our home life with funny words he made up – to get us going he would shout “Acsiones!” (a mock Spanish version of “Action!”), and impromptu performances.

In fact, the late Rabbi Thaler of Massachusetts told me that when they were in Chaim Berlin together, they had a seder every night in a classroom that consisted of mostly learning, with a few minutes of dancing at the end. He particularly recalled them dancing “Hamaavir Banav Bein Gizrei Yam Suf.” That flashback of two yeshivah bochurim in Brooklyn, a few years after the Holocaust, spontaneously recreating the atmosphere of the Splitting of the Sea fills me with joy, just imagining the scene.

Rav Aharon Feldman was one of my father’s close friends from those days. He tells me that my father once invited him into his dorm room to share a steak with him that he would prepare on a new electric grill he had bought. The secret got out soon enough, when the aroma of steak on the flame spread all the way down the hallway. The result was that so many friends came by for a piece that in the end my father had none for himself! Rav Aharon was watching him intently and concluded that he was not upset at all.

Rav Yaakov Perlow, another friend, liked to tell me about the time my father called him on Erev Shabbos on an impulse and said to be ready outside his house with a suitcase in ten minutes. “We’re going to Camp Morris for Shabbos!” They were already in their mid-twenties and had outgrown the weekday camp atmosphere, but Shabbos was something different. They had some mechanical difficulties going up the mountain and wound up making it to camp just minutes before candle lighting.

Rav Yaakov Perlow, the Novominsker Rebbe, passed away just hours after my father. I could not help but think that they were hitching a ride together to Gan Eden….

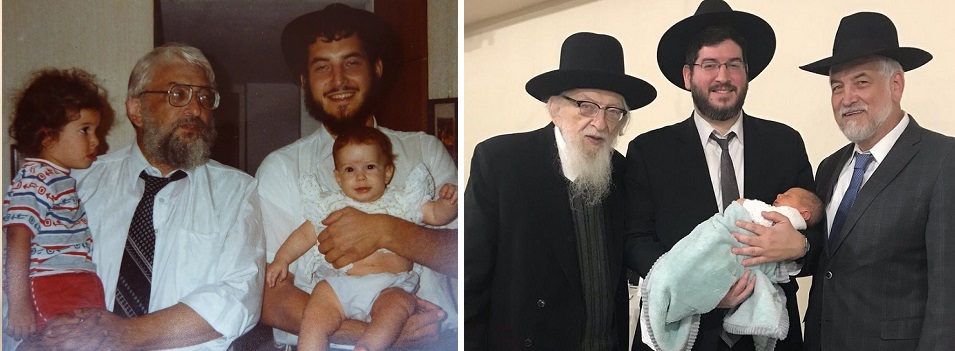

With his son (the author) and grandchildren in his younger years (l) and more recently (r)

VIEW/DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION

I was zoche to be a neighbor to Rav Homnick's brother, lehavdil ben chaim lechaim, in Jerusalem years ago.

His brother Rav Yaakov shlita related that their father was the only Shomer Shabbos pharmacist around, Itself a rarity in those days. According to the law, there was a need for him to be open very late, and he could not afford to hire another worker due to the loss of shabbos business, thus necessitating his working long hours away from his family all week. Instead, as your article mentions, it was the zemiros of their father on shabbos that brought them together once a week and uplifted them.

I also fondly recall meeting the niftar many years ago on a visit to Flatbush praying in the Landau shtiebel in the summer time. After davening, Rav Homnick gave a short talk in which he emphasized the importance we ascribe to mitzvos ben adam lachavero need be strengthened. "It did not used to be emphasized in klal Ysrael historically by the gedolim in Europe for fear we would also engage the non Jews and assimilate,," he explained.

However, nowadays he stated, that his Rabeiim held that we need to make sure to emphasize ben adam lachvero just as much as ben adam lamakom.

As a dignified and true master of ben adam Lachavero and ben adam lamakom, my brief and impressionable encounter with his persona has generated a lasting impression, as I am sure it will on all who knew him.

Yehi Zichro Baruch, and may the family be comforted among the mourners of Zion.

— R' Yehuda Levin

Oops! We could not locate your form.