Protecting What We Love Most

Parents who lost children to hot cars and pool accidents move their suffering forward so others won’t

Every year, loving, conscientious, responsible parents who think it could never, ever happen to them lose children in pool accidents or hot cars. A new initiative strives to spread awareness of child-safety education and the availability of preventative devices, because painful experience has shown that very traumatic things can happen to very good people

Sarena Cohen, an events planner and camp director in Baltimore, thought she knew all the ins and outs of pool safety. Her in-laws have a pool, she’s worked in camps, and her family frequently went swimming. All her children, with the exception of two-year-old Aliza, had learned to swim, and Aliza was never allowed to approach a pool without floaties.

“We’re neurotic about pool safety,” Sarena says. “Our family members who live in Florida have double locks on their pool gates and are always super vigilant.”

This past Pesach, she and her extended family rented a home with a pool in the Encore community in Florida. Perhaps it was the “neurotic about safety” aspect of her personality that led her to lie awake the first night of Chol Hamoed, wondering if she’d stored the local Hatzolah’s number in her phone. When she awoke the next morning, her phone was still open to her search, and she updated the information.

After two days of chag, everyone was anxious to get into the pool. A few family members dove right in, some were enjoying sitting around, and Aliza, wearing floaties, sat like a princess on the pool’s tanning ledge.

When her older daughter asked for some lunch, Sarena did a quick survey of the pool and saw there were plenty of adults around.

“I’m going inside to make some eggs,” she told them.

Aliza noticed her mommy leaving and announced, “I want to go with Mommy!”

She stood up, took off her floaties, and everyone saw her follow Sarena to the kitchen door.

No one knows what really happened after that. Aliza must have changed her mind about coming inside — she returned to the pool, unnoticed by the adults, who assumed she was in the kitchen. All Sarena knows is that a little bit later she heard her sister-in-law give a scream she can only describe as “otherworldly… the kind of scream you make when you’ve lost a loved one. Aliza was lying motionless on the bottom of the pool.”

Her husband Levi flew into action, but it was actually their five-year-old who dived down and pulled Aliza up from the bottom. Her wet hair was hanging in her face, and she was blue and completely limp. Sarena started shrieking. But she did her best not to panic.

“I’ve taken CPR classes four times — I ran a camp of 400 kids,” she says. “One thing that did stay ingrained was to stay calm. I remember looking at my feet, at my white sneakers that were pulling me toward my daughter, but I knew I had to go to the kitchen to call Hatzalah.

“I also knew to delegate. I asked someone else to call for help, and asked my brother and sister-in-law to watch the other kids. Levi started to do CPR, although he wasn’t confident in his skills, and by now my daughter was a horrifying shade of purple. She finally produced a sound that was just unearthly.”

Miraculously, just then, a neighbor in a golf cart suddenly pulled up. “I used to be an EMT on Hatzalah,” he told them.

Gershon Gershuny of Monsey and his wife had rented a golf cart, and that afternoon, his wife had pushed him to give it a try. When his wife objected that he was going too fast (although the cart only goes 17mph) he slowed down — which is exactly when they heard the commotion.

Gershon did CPR on Aliza until Hatzolah arrived. From time to time, she would make little cries.

“Is she going to live?” Sarena asked Gershon, terrified.

“Crying is a good sign,” he replied.

When Hatzolah arrived, swooping in like a band of angels, Sarena had the presence of mind to grab her phone, her ID, and her Tehillim before climbing into the ambulance with them. Off they went to a helicopter field to airlift Aliza to the Orlando Health Arnold Palmer Hospital for Children, an hour away.

“I called my parents to say Tehillim, and I myself was reciting any Tehillim I knew, any random prayer, bits of Tanya, a whole gobbledy-gook of tefillah,” Sarena says. “I was already thinking to myself, How can I tell people my daughter drowned? How will we possibly deal with this?”

Aliza continued to cry out in the helicopter, and Sarena was grateful for every cry, every indication that she was still alive. Every breath is a brachah, she realized. We never appreciate this enough.

Then, for a while, Aliza stopped making noise. Sarena was petrified.

“I thought maybe she really had died,” she says. “I started asking Hashem to help my husband and family deal with the guilt they would feel. It was a real Ne’ilah moment. I felt death. And then I felt Hashem with me. For a moment, I even felt at peace.”

In the end, however, it turned out Aliza had simply fallen asleep.

“Oops, sorry,” a paramedic told Sarena as they landed. “We were supposed to warn you she’d probably fall asleep.”

They landed on the roof of the hospital and were brought to the ER, where staff came flying out from everywhere. Sarena was instructed to stay behind a line of red tape on the floor. A chaplain and a social worker materialized to keep her company, chitchatting away as if Sarena could focus on what they were saying.

By now Aliza was breathing, but lethargic and wobbly, her eyes rolling. Her skin color was better, but not completely back to normal. Doctors tried giving Aliza oxygen. When it didn’t help, they increased it.

“There were many delicate, scary moments,” Sarena says.

Time lost all meaning as she sat there, the hours melting into each other like a watch in a surrealist painting.

At one point, someone approached her to ask, “Are you Jewish?”

He turned out to be a doctor affiliated with the local Chabad. “You’re in one of the best children’s hospitals in the world,” he reassured her. He explained what the doctors were doing at each step, offering constant assurance until Levi arrived by car an hour later.

In the meantime, Child Protective Services showed up to interrogate Sarena, digging for dirt. “It’s okay to blame one of your family members,” they said.

Back at the house, other CPS workers interviewed each of her children separately, inspecting the premises and asking the kids about how they were parented.

“Weren’t your parents watching your sister?” they asked.

The doctors drained water from Aliza’s lungs and kept her connected to oxygen, transferring her to a step-down unit. “The next 12 to 24 hours will really determine the outcome,” doctors told them.

By the middle of the night, b’chasdei Hashem, the staff was able to decrease Aliza’s supplementary oxygen, and things continued to improve. The following afternoon, Aliza’s doctors suddenly pronounced her stable and told the Cohens she could be discharged that day.

“You got really lucky,” a nurse remarked. “We see more than 30 drownings a year here, and your daughter made a miraculous recovery.”

(Emergency rooms nationwide receive 6,500 visits a year due to fatal and non-fatal drownings.)

When the Cohens brought Aliza home, the entire family was overjoyed. Sarena was floored to hear one of her daughters say, “Let’s go swimming again!”

“She’s right,” Sarena’s mother agreed. “You should go right back into the pool with Aliza.”

They did. Sarena and Aliza went into the pool, but the Cohens now have new rules. No one goes into the pool without a buddy, ever. No young child takes off his floaties, ever.

“It taught us that ultimately, we are not in control,” Sarena says. “We’re powerless. We can only do our best to take precautions.”

Happens to the Best of Us

Hundreds of children die tragically every year in accidental deaths, usually during warm-weather months. The most common incidents are pool drownings and hot car deaths, which happen when children are trapped in a car (either their parents forget them or they climb in and can’t get out) and they die of heatstroke.

The CDC reported 371 child drowning deaths in 2023, and 29 child hot car deaths, 87 percent of them children under three.

Hot car deaths jumped by 35 percent in 2024, to 39. July is the deadliest month, and 83 percent of all cases occur between May and September. But even on days as cool as 57 degrees Fahrenheit, a car can heat up by 20 degrees in just ten minutes.

“What kind of person forgets a baby?” asked Gene Weingarten in his Pulitzer Prize–winning Washington Post article, “Fatal Distraction: Forgetting a Child in the Back Seat Is a Horrifying Mistake. Is It a Crime?”

Weingarten answered his own question: “The wealthy do, it turns out. And the poor, and the middle class. Parents of all ages and ethnicities. Mothers are just as likely to do it as fathers. It happens to the chronically absent-minded and the fanatically organized, to the college-educated and to the marginally literate…. It happened to a mental health counselor, a college professor, and a pizza chef. It happened to a pediatrician. It happened to a rocket scientist.”

Weingarten might have added another category to his list of people who forget babies in cars: Frum parents. Loving, conscientious, well-meaning parents who think it could never, ever happen to them.

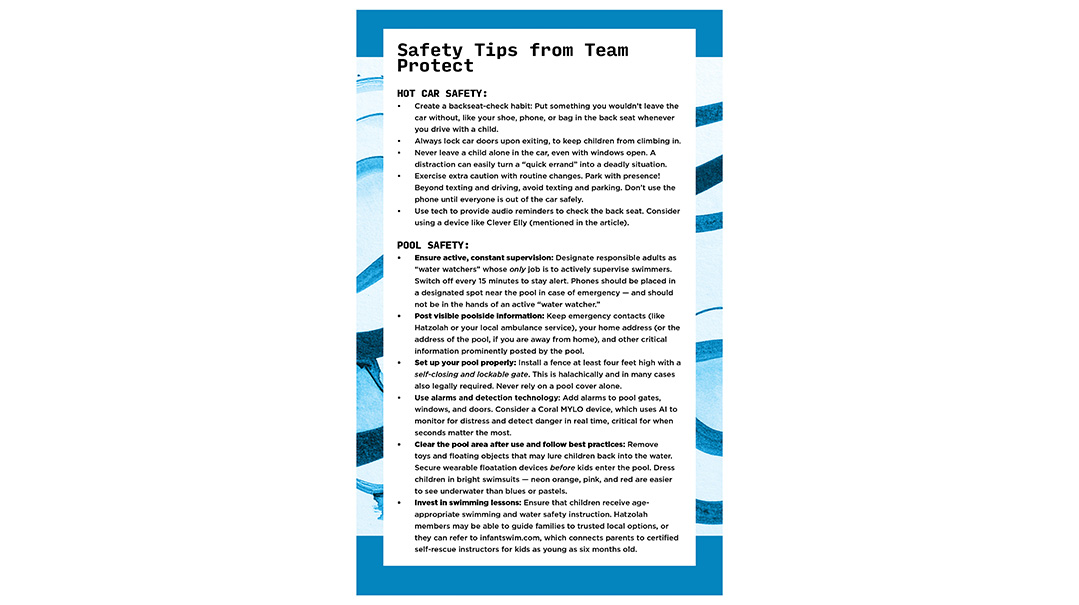

“It’s a myth that these incidents happen to irresponsible, careless, uncaring parents,” says Zalmy Cohen, a cofounder of Team Protect, an organization created to raise awareness of car and pool hazards and offer proactive solutions.

Rochel S. is a devoted stay-at-home mother, the kind who’s always picking up projects for her children to work on and baking cookies with them. She has also always been a careful parent. When she drove anywhere, she always left a window slightly open in the back, and she bought a car mirror to be able to monitor her babies in their rear-facing car seats.

Four years ago, however, she hit a rough patch. A series of health challenges left her exhausted and subject to frequent brain fog, and to compound things, her marriage was falling apart.

“I was so depleted,” she recalls. “With five young children, I could never get catch up. My husband was never around except to eat, and he made me feel like a failure if the house wasn’t spotless. My oldest child, who was about nine at the time, picked up on the tension in the home and began acting out, which added another layer of stress.”

She had loads on her mind, and when the opportunity arose for her children to attend a concert, she jumped on it. She and her husband had an appointment to see a marriage counselor at the same time, and she arranged with a cousin to sit with the children at the performance, while she and her husband went the appointment, along with her baby.

When it was done, her husband put the baby in the car and Rochel drove off, physically under the weather, and emotionally roiled.

She arrived at the concert venue, jumped out of the car and went to pick up her other kids.

“Our city is usually not so hot, but on that day, it was a sauna,” she relates. “As soon as my cousin came out, I suddenly realized I didn’t have my baby with me. I had left him in the car. I couldn’t even remember where I’d parked, and I had a blue Honda that looked just like every other frum mommy’s car in the lot.”

She ran to alert a Hatzolah volunteer who was at the concert, and started yelling for help.

“Everyone began running around looking for my car,” she says. “I can still feel that feeling of panic. I was even imagining myself sitting shivah. I felt sure my baby had died because of me.”

Fortunately, she had parked near the entrance of the venue, and the car was found relatively quickly. Her teenaged cousin opened the door and poured the contents of her water bottle over the baby’s face and into his mouth.

“I was panicked, but I saw his eyes were open,” Rochel says. “In a second, I switched from terror to relief.”

Hatzolah and the police arrived quickly. A child’s body temperature rises three to five times faster than an adult’s, and by then, Rochel’s car was 98 degrees inside. Fortunately, the baby’s temperature had only reached 102. But Rochel was told she had to go to the hospital with her baby to have him checked out.

“I almost fainted from stress and relief,” she says. “And I felt like everyone around was staring at me and blaming me.”

The baby was checked out and found to be fine, but the nightmare wasn’t over. Child Protective Services came and deemed her an irresponsible parent. They required her to be under supervision for a week, never alone with her children. Her other children were examined for signs of abuse, including checking them all over for bruises. Social workers showed up at her apartment to inspect the premises, and continued to make unannounced visits from time to time, and they put Rochel on probation for the next five years.

While Rochel felt harassed by local authorities, her community was supportive. Countless people approached her with their own stories of near-misses, and their tips to avoid another mistake, leaving a shoe or a purse next to the baby’s car seat, or buying devices that alert parents to check the back seat. Rochel was very, very careful after that, although a few years in, she finally calmed herself.

“I told myself that my child was not supposed to die in that way, that it was not his time,” she says. “Those who perished in hot car deaths, it must have been their time. But I was really zocheh to a miracle.”

Automatic Pilot

How do these bad things happen to good people? Not just good people, but people who are, as Ari Lovgren, director of operations at Team Protect, puts it, “boringly normal” and far from dysfunctional?

Most people who have studied this phenomenon say it happens because of a quirk in the way the brain functions. David Diamond, a professor at the University of South Florida, told the Washington Post that we have two memory systems: the sophisticated thought-processing memory controlled by the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus; and nonanalytical memory, housed in the basal ganglia, which control voluntary but less conscious actions (the autopilot that allows you to drive your car without focusing on what you’re doing). But during times of stress, whether sudden or chronic, higher-level functions may be weakened and cede to automatic pilot mode.

As Dr. Diamond told WaPo’s Weingarten, “The important factors that keep showing up involve a combination of stress, emotion, lack of sleep and change of routine…. Unless the memory circuit is rebooted — such as the child cries, or, you know, the wife mentions the child in the back — it can entirely disappear.”

(Diamond knows this firsthand. He’s the guy who only remembered his infant granddaughter was in his back seat as he pulled up to a mall because his wife reminded him. He freely admits that had he been alone, he could easily have forgotten the child.)

We hear often about the dangers of parents being distracted by cell phones, but most hot car deaths and near-misses aren’t caused by getting calls per se, but by receiving distressing calls.

“A friend of mine was taking a toddler to playgroup shortly after his wife had a baby, and he got a call while driving that there had been a flood in his office,” Zalmy Cohen relates. “He was so upset that he skipped the playgroup and ran directly to his office, running on pure muscle memory and forgetting all about his daughter. The child was alone in the car for 20 minutes, and this was in Miami, where temperatures are high. She was okay, but it was a scary close call.”

Hot Spot

Yehuda Freundlich from Passaic, New Jersey, got his own sobering reminder about the importance of safety devices during a family trip to Eretz Yisrael for Pesach in April 2025. His wife had had twins that year, and between the babies, four other young children, and jet lag, they weren’t getting a lot of sleep.

Before Yom Tov, Yehuda would drive each morning to the nearby Nechama Bakery to bring home rugelach and Danishes. One morning, he offered his wife that he’d take along the twins. He brought them into the bakery with him, and then after strapping them into their rear-facing car seats, put the bag of pastries on the floor beneath them and drove home.

When he got back to the house, functioning on autopilot, he grabbed the bag and went into the house.

Everybody began enjoying a convivial breakfast when his wife suddenly piped up, “Yehuda, where are the babies?”

Yehuda froze. “Omigosh!” he yelled, rushing to the car.

“It had only been about five minutes,” Yehuda relates, “and fortunately it was only April in Israel, so the weather wasn’t hot. The babies were fine. But I was traumatized.

“It really drove home to me what I had been hearing all along about parents who lose children in hot-car accidents. They’re not freaks of nature, they’re not careless. I myself am not a spaced-out person. I just got used to certain habits, and I hadn’t slept much, so I didn’t process the change. It was mind-blowing. No one is invincible.”

The ironic thing was that Yehuda knew all about the danger of accidentally leaving children in hot cars; in fact, since late 2024, he’d been involved with Team Protect, participating in meetings to evaluate products that help protect children from dangers like these.

Yehuda, the VP of a furniture-manufacturing company, manages a team of engineers, designers, product development specialists and marketers, and before that he worked in mobile app development. He describes himself as a guy who was “an ADHD kid who always loved new ideas and technologies.”

He also has a big heart. When he received a mass email from Nechama Tauber, who helped found Team Protect after the hot car death of her three-year-old son Sholom a”h, he felt so terrible about her loss that he responded directly to the appeal.

“I would love to contribute, but my maaser is already committed right now,” he said. “But I’d be happy to join your team and help evaluate products for child safety.”

Yet until he learned the hard way, he didn’t buy any of the products himself. “Here I was, spending hours learning about these devices, yet I was too lazy to spend the 20 bucks for myself,” he says.

One of the products that Team Protect promotes on its website is Clever Elly, a device that connects to a car’s cigarette lighter and plays an audio message reminding the driver to check the back seat. Team Protect worked with Clever Elly to develop a device specific to the Jewish community that plays familiar voices like Avraham Fried.

“The tone and speaker vary each time, so your brain doesn’t get used to hearing the same voice and start tuning it out,” says Yehuda.

The device — which is being distributed under a campaign at 59seconds.org — was invented by three Jewish fathers from Australia, who told Team Protect that, perhaps surprisingly, their biggest customers aren’t first-time parents.

“They learned that first-timers are sure they’ll be the best parents, that they’ll never forget a child in the car,” says Yehuda. “The best customers are parents having their second child, because by now they’ve learned that nobody’s perfect. Grandparents are also frequent customers, because they often offer to take grandchildren with them, but are no longer in the habit of putting kids in and out of the car.”

Sounding the Alarms

When Rabbi Menachem and Nechama Tauber of Coconut Cay, Florida, lost their angelic three-year-old son Sholom in a hot car accident in July 2022, they struggled for months to process the intense, complex emotions brought on by their loss. But then they courageously moved forward to transform their grief into an initiative to make sure that no other parent should go through what they had suffered, and conceived the idea to create a campaign to raise awareness.

“They turned their pain into purpose,” says Ari Lovgren.

As Sholom’s second yahrzeit approached, Rabbi Zvi Boyarsky, best known for his work as director of advocacy for the Aleph Institute (an organization offering support for Jewish people in prison and their families), approached Nechama via a mutual contact. He himself had been thinking about starting a safety initiative.

“I always had a soft spot for parents who suffered these hot car tragedies,” Rabbi Boyarsky says. “When I was in kollel in Lakewood, I heard of a few of them, and I was always shocked by how many there were.”

As for pool deaths, he feels personally connected: Over ten years ago, his then-three-year-old daughter almost drowned — while he was nearby watching his son — when his wife briefly walked away to get her father a bottle of seltzer.

Nechama shared with Rabbi Boyarsky that she and her friend Fayna Pearlman had obtained an OU Accelerator Grant to help launch Team Protect. Rabbi Boyarsky called Zalmy Cohen, his childhood friend from Montreal, who had earned his fundraising and organizational stripes by conceiving and launching the Hatzalahthon fundraising campaigns.

“A few of my friends had had close calls or tragic calls — in fact, one friend’s child is brain dead after being found in a pool,” Zalmy says. “Rabbi Boyarsky called me in August of 2024, and basically overnight we formed Team Protect.”

Nechama was joined by Sara Dorsky, whose child was niftar in a pool accident three years ago. Together they made video clips for the website, and along with other parents who have experienced tragedies and near-misses, serve as ambassadors for the organization.

Team Protect is on a registered nonprofit and partners with many health and safety organizations: Hatzalah, Chaveirim, For the Babies, Kids and Car Safety. The devices it sells on its website are sold at cost.

“We don’t want the liability of selling for profit,” Zalmy says. “But we do try to negotiate discounts. Coral MYLO [a pool safety monitoring system that uses AI technology to recognize if someone in the pool isn’t breathing] took ten million hours of research to develop, so it sells for $1,800, but we managed to convince them to sell it for $1,000 through us.”

The problem is that, as Freundlich’s experience attests, people assume they’re invincible, that “it could never happen to me.”

“Very few people think proactively,” Yehuda says. “Look at me — for all my research into these gadgets, I didn’t think I’d ever need one myself.

“Chaim Sinai Orbach, the owner of the CSO Radio shop in Lakewood, produced and patented a device called Ride and Remind that gets hardwired into your car. When you exit, you have to push a button to deactivate the alarm. He has sold thousands of them, but 99 percent of the people who buy them do so only after a close call. That means only one percent of people are proactive.”

Toyota recently approved the development of a system called Cabin Awareness, a software system that uses radar technology to detect the presence of a breathing person when the car is off. If it detects a child, it triggers a call to the parents, and if there’s no response, it calls the police and 911 with a location.

“One in four hot car deaths happen when children climb into a car parked on the street or in a garage and can’t get out,” Yehuda says.

The Team Protect site displays many options for car and pool safety, including Clever Elly, Ride and Remind, Coral MYLO, and the Techko Pool Door Alarm that goes off if someone opens the gate without using the adult bypass option. Team Protect negotiates discounts for the community and sometimes distributes lifesaving devices.

“When it comes to drownings, there’s a myth that it only happens when there’s no supervision,” says Zalmy Cohen, and he’s quick to dispel it. “Eighty-eight percent of drownings happen in residential settings, when there are people around. Another myth is that if a child starts to drown, you’ll hear him. An adult will thrash around, but a child’s hand swishing the water is inaudible.”

“You always need multiple layers of protection,” says Ari Lovgren of Team Protect. “You should even post the local Hatzolah number in plain view, because people often forget it when they’re in panic mode. If you’re on vacation, post your address, because you could forget it under pressure and give Hatzalah your home address.”

But while technology can help prevent tragedies, it’s important to keep in mind that any device can fail. A pool lock may fail to close, a beeping device may not beep.

“We had safety equipment [around our pool] that we assumed was enough,” Sara Dorsky said in her video clip for Team Protect. It failed, and her daughter was the victim.

But Sara and Nechama find meaning and comfort in doing whatever they can to spread awareness to other parents of the hazards that their children are susceptible to and what they can do to try to keep them safe.

“This pain will never go away, and I don’t want it to,” says Nechama. “I want to use it to prevent another tragedy from happening.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1072)

Oops! We could not locate your form.