Praying Together

N

owadays, you simply can’t miss the Achdus Israel community in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The “Moldes Street Empire,” as a friend of mine nicknamed it, has expanded into two buildings that house a primary school, a high school, a mikveh, a yeshivah ketanah, a yeshivah gedolah, a Bais Yaakov, three minyanim... but when my parents joined the kehillah, it was merely the yekkishe shul of the Belgrano neighborhood.

In 1929, a group of Orthodox Jewish immigrants from Germany decided they needed a place to daven in their new South American abode. They started a minyan and eventually bought property to build a shul. Here I must explain that Belgrano is not (or at least, it was not) a frum area, like the neighborhoods of Once or Flores, but rather home to completely assimilated Jews. But as my father always says, “Yekkehs love to feel different.” That decision not to settle in a more religious Jewish area would eventually lead to a vibrant chareidi community in a place that, until then, was a Torah desert.

My family came to Achdus Israel following my father’s search for a more yeshivish minyan. And I must say, it was a very awkward experience at the beginning. We used to attend the Beis Chabad in our neighborhood, but on the insistence of a good friend, we landed on Calle Moldes.

“Something new is going on there,” he told my father.

That “new thing” was something of a historic event: a minyan of Sephardi mispallelim in search of a space had approached Rav Daniel Oppenheimer, the rav of Achdus Israel, for room in the building, and he had approved their request. A few years later, I found out that this had not been an easy decision, and that Rav Oppenheimer acquiesced only after receiving the advice of gedolei Yisrael. When the Sephardi minyan started, this family friend, a fluent Yiddish speaker with Polish roots, immediately fell in love with the warm environment.

So there we were: the Ashkenazi family in the Sephardi minyan in the yekkishe shul.

One of my most precious memories is the Shabbos davening because, as I explained, it wasn’t so conventional. When I was a bochur in the kehillah’s Chazon Yechezkel yeshivah, my rosh yeshivah, Rav Daniel Mohadeb, once told me that although it was convenient to daven in the yeshivah minyan, it was also important to join my father for one of the tefillos in the Sephardi minyan.

So that was the schedule: Shabbos night I was with the Sephardi minyan, joyfully singing Shir Hashirim in what was for me a strange tune; for Shacharis and Minchah I joined the yekkishe bochurim and avreichim in the yeshivah; and then for Maariv and the “Rishon L’Tzion Havdalah,” I rejoined my father.

The arrival of the new minyan not only changed my life, but also imparted a new chiyus to the kehillah. Around this same time, Buenos Aires saw a surprising wave of teshuvah, and Achdus Israel was a beacon for families thirsty for Torah. The shul soon became a melting pot, and many new families joined the kehillah’s Yosef Caro school. The stream of newcomers on Shabbos slowly but steadily created a pressing need for more space. Rav Oppenheimer used to reminisce how hard it was at the beginning to find a minyan, and how many times they had to canvass the few Jewish shop owners in the neighborhood to reach a quorum of ten.

One feature of the shul was a constant through the years. On any given day, one could come to the beis medrash and hear someone leining (or should I say screaming) a parshah from the Torah — not the one for that week, or for the next, but for three months hence. The voice would thunder one pasuk again and again, until he joyfully screamed, “That’s it! There we go!” Then a pleased child would, finally, move on to the next verse.

It was Rabbi Buby Katz — a tall blond man, always with a smile on his face and a kind word in his mouth — teaching a young boy his bar mitzvah parshah. I’ve never seen someone put as much passion into something as he did teaching those kids. Buby, as everyone called him, carried a heavy burden due to personal circumstances, but he was inspiring to all of us.

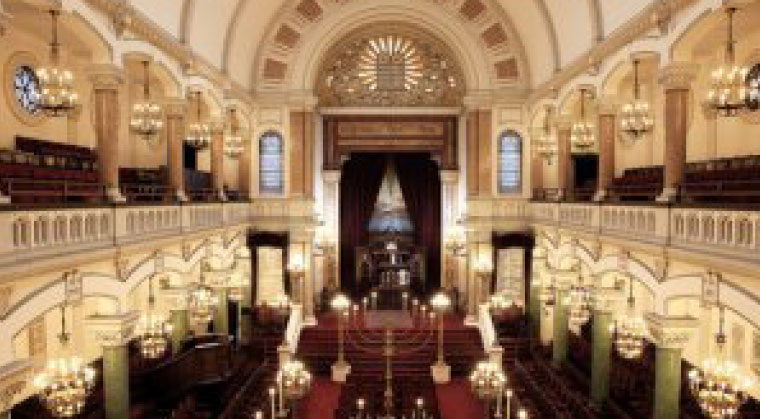

Another unforgettable voice was that of the shul’s baal korei, Rabbi Yosef Goldschmidt. When first we joined the kehillah, it struck me that his tender and somewhat “high-toned” voice was out of place in this old-style shul, with its heavy wooden benches and high ceilings. But when our first Tishah B’Av at Achdus came around, and we all sat on the floor under dimmed lights, unable to see over the benches beyond our row, suddenly, Rabbi Goldschmidt’s wail condensed thousands of years in exile. Eichah yashvah badad… Since then, it’s been hard for me to hear it being read by someone else.

But although all the davening at Achdus holds special memories, the main highlight was the mutual respect and kavod everyone in the kehillah showed each other, starting from the rabbanim. The three minyanim would have Shalosh Seudos together in the dining room, and one of the rabbanim would speak — Rav Oppenheimer, Rav Mohadeb, or Rav Baruch Mbazbaz of the Sephardi minyan. And all would listen with the same respect. During the week, it wasn’t surprising to see someone from the Sephardi minyan consulting with Rav Oppenheimer, or one of the yekkes asking a sh’eilah of Rav Mbazbaz.

Shabbos Hagadol was another very special moment: All the minyanim would join together in the old yekkishe shul to hear the derashah from the Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Mohadeb. He would delineate the differences “for those who eat kitniyot… and for those who don’t….” Despite the wide range of personal backgrounds, l’ maaseh we were one big kehillah.

Achdus Israel kept right on growing after I left for Jerusalem. I remember as a bochur going back home for Pesach and finding a new floor added to the building to house a Sephardi shul. At the same time, the new building for the high school opened right in front of the old shul. On my most recent visit, I met some old yeshivah friends of mine from Jerusalem at the kollel there; they had married girls from families in the kehillah.

It all shows the power of doing Hashem’s Will. Just picture those first ten German immigrant families struggling to make a minyan. They probably never thought about developing a school, expanding into another building, creating a lighthouse for Jewish life in an assimilated neighborhood, hosting people with completely different minhagim in the same place, and changing thousands of lives.

Or maybe I’m wrong. Maybe they did think of everything. Maybe that generation was able to see further. And, maybe, that’s why they called the kehillah Achdus Israel.

(Excerpted from Mishpacha, Issue 759)

Oops! We could not locate your form.