Street Smarts: Prayers and Providence

| September 29, 2020So Avi reinvented himself as a taxi driver, learning new skills, mastering new routes, and meeting new people. Most of all, he says, his career change meant a boost in bitachon

The assignment: Find the route, site, or scene that best captures the beauty and charm of Jerusalem.

The driver: Avi Mizrahi of Bar Ilan Taxis

The theme: Nothing frames the beauty of a city better than its holy history

"T

Avi Mizrahi’s affirmation applies perfectly to today — when he woke up this morning, he had no idea he’d be accepting a challenge to take our readers to the location that best showcases Jerusalem. He definitively decides the Old City is our destination, but the route, he says, is part of the experience too.

“‘For sure we should start with Kever Rochel. If you’re coming to Yerushalayim for the first time you can’t miss Mamma Rochel,” Avi tells me as we pick up our photographer, Esther Tscholkowsky.

If you’re expecting the quintessential Israeli taxi driver — an excitable Sabra vehemently espousing his views on politics and other drivers on the road, eating a falafel with one hand while smoking a cigarette with the other — the ride with Avi is a little different. He pleasantly and coherently answers my questions but doesn’t chew my ear off. He’s the furthest thing from prickly: easygoing, calm, and unassuming. He tells us that one of the best parts of his job is meeting all sorts of people, and he seems to genuinely like all of his customers.

Maybe Avi’s mild manner comes from the time he spent in America, working as a locksmith. His English, picked up from the ten years he lived in the United States, is certainly better than my Hebrew (no comment on the number of years I’m living in Israel). It’s no wonder that about half his clientele are Anglo; I’m sure his Americanized demeanor makes them feel comfortable. He, in turn, is impressed by his clients and all the chesed he sees. “It’s unbelievable; so much chesed. I see things, I hear things — they’re in my car, so I hear,” he says almost apologetically, explaining that he can’t help but notice what people are up to, and a disproportionate amount of the time, they’re involved in helping others.

“A few weeks ago, I picked someone up at a baby store in Ezrat Torah, just before Shabbat. He starts loading my car with ten car seats — some infant seats, some for bigger children. He tells me he’s starting a gemach. He doesn’t have much of an income and his wife recently lost her job, but he made a neder to start a gemach so people can keep their children safe when they travel. He has no job and no money, and he’s doing chesed. Unbelievable. So of course, I gave him a discounted fare.”

On our way to Kever Rochel, Avi shares that his current profession is a relatively recent development. Until three years ago, he worked as a delivery man for the Philip Morris tobacco company. During the last five of the sixteen years he worked for them, the company had relocated to Ashdod.

“I was driving back and forth to Ashdod every day. I realized I could avoid the long-distance drives, stay in Yerushalayim, and get paid to drive all day,” he says.

So Avi reinvented himself as a taxi driver, learning new skills, mastering new routes, and meeting new people. Most of all, he says, his career change meant a boost in bitachon.

“When you’re a taxi driver, you understand that everything is siyata d’Shmaya. You wake up in the morning, and you don’t know if you’re going to earn anything. Two drivers can set out from the same place, work from 8 a.m. till 6 p.m. — and one can make 300 dollars while the other can make nothing. If you don’t have faith, you can’t do this job. You’ll go nuts.”

If you do have faith, though, you’ll clearly discern a Heavenly Hand navigating your route. Once a rav asked Avi to drive him to Arad — quite a distance. After dropping the rav at his destination, he was on the phone with his cousin as he headed to Route Six back to Jerusalem — a long and fare-less drive. “Stop your car and turn around!” his cousin said. “I just got a message from a woman in Arad now, looking for a ride to Yerushalayim.”

“Things like this happen all the time,” Avi says. “If you pay attention, you see it happening before your eyes.”

Our taxi slows as Avi drives through the enormous, imposing concrete walls that protect those coming to daven at Kever Rochel. Avi steps out and speaks to the manager, asking for special permission for us to pop into the kever for a quick photo between groups. Due to the COVID-19 crisis, only a limited number of people are allowed into the kever at a time, for about ten minutes per group. Ushers urge women to stick to the time frame so the group waiting behind them can enter.

Our visit to Mamma Rochel — the matriarch who still pleads on behalf of her precious children, particularly those waiting for children of their own — reminds Avi about an American yungerman he’d taken to the airport several times over the years.” He called me about a year and half ago to take him to the airport again. On the way, he asks me for a brachah. I tell him, ‘You learn in the Mir. You have millions of rabbanim there, why would you want a brachah from me?’ I thought he forgot about it, but when we arrived at the airport he asked again, ‘Avi, please give me a brachah. You’re a tzaddik, your brachah means a lot to me.’

“So I ask him what he needs a brachah for. He says he’s married for four-and-a-half years, and he and his wife have not yet had children. I didn’t know what to say. So I helped him with the luggage, put on my kippah, and gave him the best brachah I could give.

“A few months later he calls me again to go to the airport. This time he’s with his wife. I never met her before. He introduces us and goes upstairs to bring the luggage. She tells me, ‘Avi, my husband loves you. He talks about you all the time.’ I said, ‘I like him too, I’ve known him a while.’ When he comes back down with the luggage, he tells me they’re expecting a simchah sometime soon. I was so happy. Maybe my brachah did something?

“In November, I took my son to Madrid for a short vacation. When I got back and turned my phone back on, I saw this yungerman had been calling me like crazy.

“I called him back. ‘What’s wrong? I see you keep calling.’

“He told me that his wife had a boy; he wants me to come to the bris. I was the only one there not chareidi, in jeans and a T-shirt. But I knew the whole family. I’d driven all of them. I felt like it was my simchah too. I was so happy for them!”

We’re back on the road, within the confines of Jerusalem again. We still haven’t reached our destination, but Avi’s right: The route is part of the experience too.

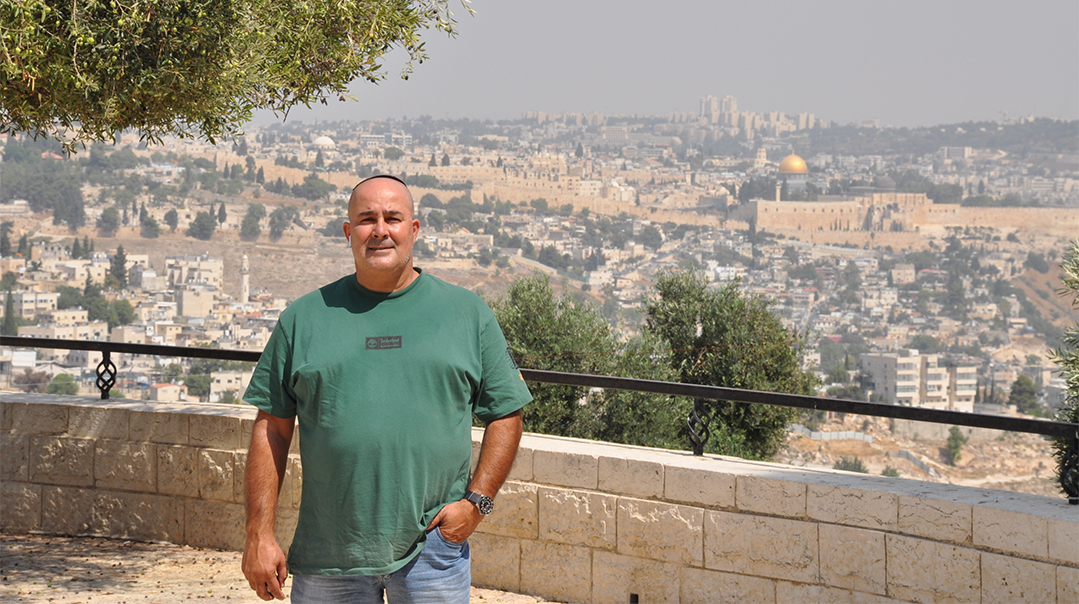

Avi says we must see stop on our way to the Old City to see the view from the Tayelet, the Haas Promenade.

“I didn’t tell you yet why I left America,” Avi says as we near the promenade. “I came back to Israel because my father was sick. He needed a kidney transplant. I have three sisters and none of us was a match. We found a donor, but it was a very expensive surgery, with so many logistics to arrange too. I took all the responsibility to make it happen. You could say I did kibbud av, right? Six or seven months later he got cancer and died. At least we tried, at least he had those months.”

Avi heads for a parking spot, and his voice turns contemplative. “My father passed away in 2003. In 2007 my youngest daughter was born. When she was less than six months old, she was diagnosed with cancer. Baruch Hashem, she recovered. I believe we had the hashgachah that we had with her because of what we did for my father.

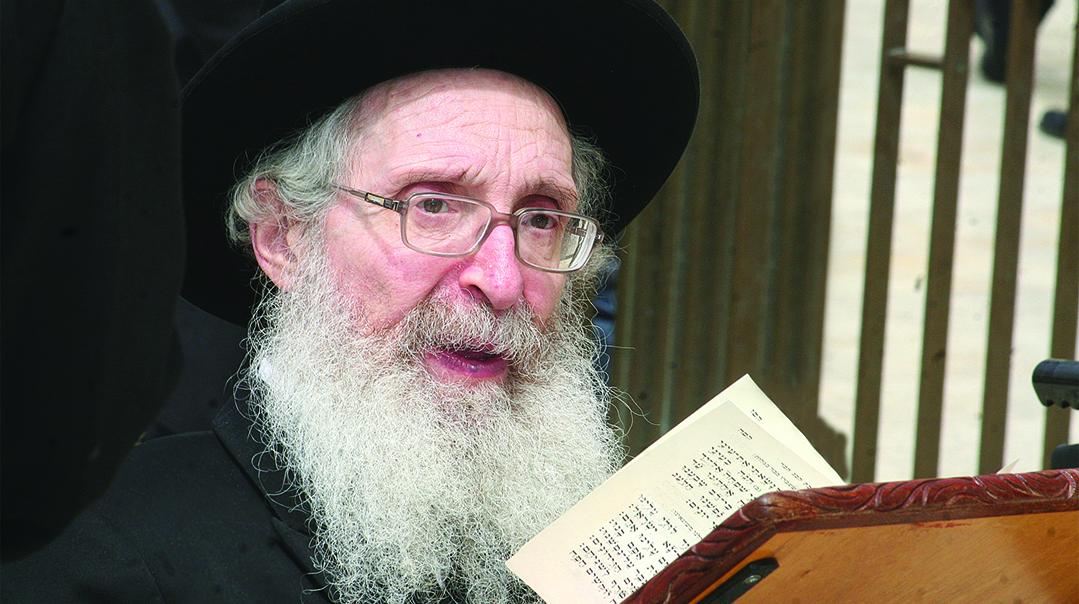

“When my daughter was sick, someone arranged for me to see Rav Mordechai Eliyahu. I’m not religious, as you can see, but I’m a believer. I have emunah. Before we went in to the Rav, I told my wife, ‘If the Rav tells us to do something we have to do it, or else there’s no point in going.’

“He told us we have to change our daughter’s name. Not to add a name like you usually hear; to change it altogether. Her name was Yuval. We asked him for some suggestions. ‘Shira or Noa,’ he said. On the spot, we chose Noa. ‘Do you know what Noa means?’ the Rav said. ‘The name is spelled Nun-vav-ayin-hey. Those letters stand for Nissim ve’niflaot oseh Hashem — Hashem performs miracles and wonders.’ Everything is from Him,” Avi finishes, as we pull into the parking lot of the Tayelet.

My breath catches, and I’m not sure if it’s from that story or the view. Jerusalem is sprawled out before us, and we can see for miles. There’s a map identifying the landmarks, and Avi points out the Kosel and other places of note. I could look at this view all day and not get enough of the splendor and majesty.

Back inside Avi’s taxi, we ask him about the security camera he’s installed.

“It’s a good thing to have in case of an accident, chas v’shalom,” he explains. “If someone smashes your car and then claims it wasn’t their fault, you have it on camera. It also shows what’s going on inside the taxi. My friend once stopped to take a couple with a baby. The woman got in and asked the driver to help her husband with the stroller. When the driver got out, the woman took his money from the compartment he kept it in. But it was all on camera, so she was caught.”

But most passengers are honest people looking to get to their destinations in as pleasant a way as possible. And that’s what Avi tries to give them. On one memorable occasion, he tells us, he took a group of seminary girls to the airport late at night. On his way back home, his phone rang: It was the mother of one of the girls. (“Yes,” he explains, “I’m the type of driver that the girls know me, their mothers know me, their brothers, too…”)

Avi figured she was calling to thank him, but no — she asked him to please, please turn around and get the girls from the airport. Their flight had been canceled. Of course, he readily agreed and brought the girls back to their dorm in Jerusalem. It was late at night when he got back home, but just before he went to sleep the mother called again. The girls’ flight had been rescheduled for the morning. Would he be willing to pick them up again at 5 a.m.?

“I went to sleep for a couple of hours and then took them back to the airport,” Avi says. “I was happy to do it. That’s my job, isn’t it?”

The drive from the Tayelet is quick. Even though parking in the Old City is for residents only, with just a few words from Avi, the guard lets us in, and Avi pulls up in front of the rebuilt Hurvah shul — which he assures us is a magnificent must-see for tourists. Avi promises the guard we wouldn’t stay long, so after a look at the Hurvah and glance around the Jewish quarter, he escorts us back inside the car.

We don’t need Avi to tell us that the climax of any trip to Jerusalem would be the Kosel. There’s only so close Avi can take us, but true to his word, he’s chosen a route beginning and ending with holiness, and saturated with prayer.

It’s hard to leave the Kosel, but Avi has a surprise: There’s another stop on his itinerary, the gravesite of Dovid Hamelech right outside Shaar Tzion. As serendipity would have it, our photographer, Esther Tscholkowsky, lived on Har Tzion for 22 years, and she has a few things to show us. As she points out the house she used to live in, we discover the courtyard behind it has been adapted for outdoor weddings to meet our new, socially distanced reality.

Esther leads us to Dovid Hamelech’s kever through the Chamber of the Holocaust — the original location of Yad Vashem. The walls of several connected courtyards have been hung with stone tombstones engraved with the names of each community lost in the Shoah.

This memorial to such unprecedented destruction and pain is an apt introduction to the resting place of the composer of sefer Tehillim. We daven by the kever of Dovid Hamelech, the man who dreamt and sang of this city with words that still ring true thousands of years later. It’s the perfect finale to a perfect tour hitting all the right notes.

As we bid goodbye to Avi, I can’t help but see the irony: I’ve spent the morning with a cab driver who describes himself as “not religious,” so how is it that I’ve spent the entire time davening at mekomos hakedoshim?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 830)

Oops! We could not locate your form.