One Pure Pitcher

| December 9, 2020How did the Greeks actually contaminate all that oil, except for one small pach, considering that tumah, spiritual defilement, has very specific parameters?

What was the secret of the solitary, undefiled pach hashemen found hidden in a ransacked Beis Hamikdash?

The laws of tumah and taharah, made clear by a rabbi who never goes anywhere without his props, can help bring us into the mindset of the conquering Greeks, bent on destroying any vestige of G-dliness in the holiest place on earth

Triumphant footsteps. Jeering shouts. Clanking armor. The rank odor of sweat and alcohol mingles with faint echoes of the sublime scent of the Ketores. The cries and groans of the wounded and dying combine with the hoarse chants of the conquerors — some of them their very own brethren.

The invading hordes, bent on destruction and defilement, stomp their way around this holiest of sites, plundering precious vessels and smashing what they can’t carry. Yochanan, the righteous Kohein Gadol, has been assassinated, and the bloodthirsty Syrian-Greek ruler Antiochus Ephiphanes, having enacted a series of harsh decrees against the Jews, encourages the bloodshed and degradation. His men gleefully swig from earthenware amphoras of wine, break open sealed flasks of oil and spill them over the blood-and mud-mottled floor. One bulky centurion stashes a flask or two in his scabbard to take home to his wife. Another considers smearing the quality liquid into his skin. A third stabs at oil seals with the point of his sword, sowing destruction for the sheer fun of it. His comrades follow suit, their mocking voices echoing through the Heichal.

This is the tragic scenario our minds conjure up when we envision the Syrian-Greeks overrunning the Beis Hamikdash and contaminating the entire inventory of holy oil designated for the Menorah. The Greeks, joined by their Jewish-Hellenist allies, were bent on removing all vestiges of spirituality from the Jews who stubbornly clung to a narrative where an omniscient G-d was present and involved in their lives — and there was no place more tangible than the Beis Hamikdash where the connection of the physical world to its spiritual core was revealed.

But how, in fact, did the Greeks actually contaminate all that oil, except for one small pach, considering that tumah, spiritual defilement, has very specific parameters?

It’s actually a question that commentaries and poskim have grappled with over the nearly 22 centuries since the Chanukah miracle, and one that Rabbi Doniel Orzel — a rosh kollel and rav of Eitz Chaim in Manchester, England, popular for his hands-on halachic presentations to live and virtual audiences — believes he’s solved.

Not as Far as We Think

“As with all halachic scenarios,” Rabbi Orzel explains, “there is the superficial outlook and the deeper, more analytical way of thinking. We know that the Yevanim made the oil tamei. But did you ever wonder how they made it tamei? In order to penetrate the depths of the Chanukah dynamic, we need to examine some basic concepts and halachos of tumah and taharah.”

These intricate halachos were once a mainstay of Jewish life in Eretz Yisrael, familiar to everyone, as the Gemara tells us (Sanhedrin 63b) that “they checked from… Geves to Antifras, and they did not find a young boy or girl, a man or a woman who had not mastered the halachos of tumah and taharah….” In the wider world, when a person left his home, he could not be certain with whom or what he would come into contact and which precautions he would need to take to remain tahor, but in Eretz Yisrael, everyone a person encountered, unless adorned by some kind of obvious siman, was tahor.

Although today we lack most of the practical applications of these halachos, Rabbi Orzel points out that this area of Jewish law is not as distant as we think, and in fact still impacts our lives.

“Any practicing rav will encounter sh’eilos of tumah and taharah during his career,” he says. “Some examples: Where is a Kohein allowed to walk and travel? Does an air route pass over a cemetery? Is the man-made schach mat I bought mekabel tumah, or is it kosher for my succah? Can all materials be used for the building of a mikveh?”

But as the average Jew does not come across tumah and taharah on a daily basis, we take comfort in Chazal’s dictum that learning about a mitzvah is equivalent to performing it.

“Tumah is a spiritual contamination that can be transmitted,” Rabbi Orzel defines. “Today, with the proliferation of coronavirus, l’havdil, it’s not difficult to imagine an invisible substance that’s transmitted through touch, or even the air.”

But how can we visualize it, and what does it mean to us?

Seeing Is Believing

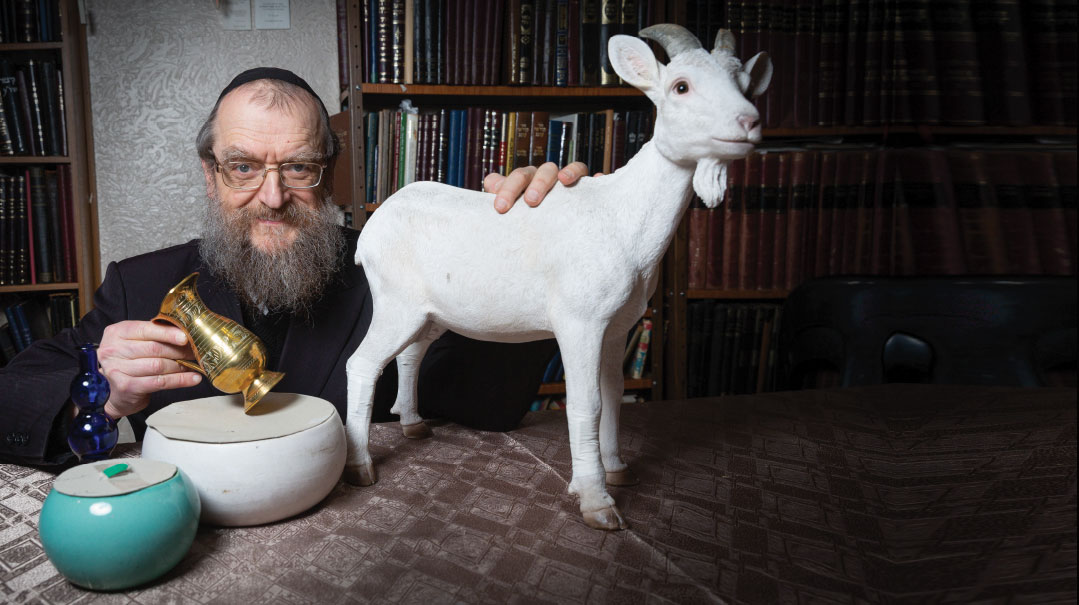

Rabbi Orzel is particularly suited to explain the concepts in a way even a lay audience can understand. For the past 20 years, he’s been delivering hands-on halachic presentations with a vast array of props acquired from around the globe, and a personable and crystal-clear style.

He says his presentation style was largely influenced by his father, Reb Avrohom Orzel of Basel, Switzerland, “an extremely down-to-earth man with an affinity for practical halachah.” Rabbi Orzel recalls him clipping a photograph out of a magazine of a wine cellar with barrels stacked from floor to ceiling. He then placed the picture in his Mishnayos Pesachim, as a real-life visual aid in the machlokes between Beis Shammai and Beis Hillel regarding how far one must go to search for chometz.

Another source of inspiration was an elementary-school rebbi in a Zurich cheder. The rebbi kept a bookcase display where each shelf was lined with artificial grass and sported plastic animals representing all of the korbanos for each of the Yamim Tovim. This long-ago visual display captured Rabbi Orzel’s imagination and inspired his own presentations on korbanos in the years to come.

His own personal foray into the world of show-and-tell halachah took place when he was substituting for a lively Gemara class of pre-bar mitzvah boys. His job was to explain the idea of a “get mekushar,” the special divorce document issued to Kohanim. Before the class began, he took a piece of paper and folded it and stitched it in the requisite fashion, so that the boys would clearly understand the special method of binding and recall it years down the line.

Before giving his first shiur on hilchos mikvaos, Rabbi Orzel concealed two huge wooden crates behind a curtain, each representing minimum sizes of a mikveh. He says he’ll never forget the excitement that was aroused when he reached behind the screen and produced them.

“All it was, was a couple of boxes,” Rabbi Orzel says, still a bit wonderous. “Seeing the immense power of demonstration moved me to brainstorm as to what other halachic topics I could depict visually, and over time, my repertoire evolved.”

At Succos time, for example, Rabbi Orzel has a popular presentation about the unusually large volume of korbanos brought during the eight days of Yom Tov. To enable his audience to visualize just how large the quantity of animals is, he shows them thirteen plastic bulls, two rams, fourteen sheep, and one goat. “All of these were for the Korban Mussaf,” he clarifies. “I had an additional two sheep for the tamid shel shachar and bein ha’arbayim, and another two sheep in case it’s Shabbos.”

He also keeps a life-size ceramic goat and a full-scale calf, plus a chalaf (shechitah knife) and a gold, pointed vessel, with which he’s able to demonstrate the four main avodos of every korban: shechitah, kabbalah (collecting the blood), holachah (carrying it to the Mizbeiach), and zerikah (sprinkling or pouring the blood on the Mizbeiach).

Rabbi Orzel tackles a plethora of topics, accompanied by visual aids, for his audiences. He has a basic shiur on hilchos mikvaos with a selection of mini mikvaos and boros (pools) made of plastic, as well as pipes, faucets, a pump and a trap.

“Parshas Shemini has plenty of potential for learning with the assistance of visual aids,” he says. “I once used a selection of neveilah meat samples including the genuine foot of a bull and some parts of a chicken during a demonstration. I’ve taught the halachos of eiruvei chatzeiros in a hall, using the existing walls of the hall as props. A recent addition to my repertoire is a reality demo of the seven mitzvos of the eglah arufah process from parshas Shoftim.”

On another occasion, for Manchester’s “Start Your Day the Torah Way” program, Rabbi Orzel convinced a farmer to bring live sheep for a shiur on hilchos Korban Pesach. On another “Start Your Day” shiur on kosher and non-kosher animals, Rabbi Orzel again produced live props — a pair of dazed, fluffy rabbits.

Regarding his wide range of visual aids, some he’s made himself, others were gifted to him and the rest were purchased from locations all over Europe.

“The ceramic goat is from Leicester. The life-size sheep and the calf were from Leeds. The plastic animals are beautifully designed by Schleich of Germany, and the knife is from an elder shochet who used it for many years. The mikvaos are plastic containers with added polystyrene stairs and large homemade LEGO figures.”

When it comes to learning certain areas of halachah, even adults will admit that visual aids not only bring abstract subjects to life, but also aid in long-term memory retention. Especially in the more complex areas of halachah, props have proven to be crucial in consolidating intricately detailed information.

There is one downside, though. “As soon as I step up to the podium,” Rabbi Orzel relates, “be it a chasunah, bar mitzvah, or bris, someone in the audience always shouts, ‘Where are the props?’ But then I realized that one simple visual aid is sufficient to draw listeners’ attention. Before one unexpected speech at a wedding, I had a quick walk through the kitchen, where I found an enormous knife. I demonstrated the perseverance required to sharpen a knife by hand, and then proceeded to compare it to life’s struggles.”

At his youngest son’s wedding in Gateshead, Rabbi Orzel informed the guests that he had brought them a “real, live prop.” With his reputation for producing live sheep and rabbits, they were unsure of what to expect, when he gestured to his son and announced that it was non other than the chassan himself….

A Touch of Tumah

Rabbi Orzel’s presentations, generally directed at the more complex and little-known areas of halachah, have opened doors for people who never thought they could grasp the intricacies of these subjects. The laws of tumah and taharah are a classic example.

And that’s how the subject morphed into his popular “Taharos Tour,” which he uses to explain the background of the Chanukah miracle and what really happened to all those jugs of defiled oil.

For starters, he explains how any person affected by tumah “contamination” becomes forbidden from entering the Beis Hamikdash or eating terumah or kodshim. Likewise, any item that is affected becomes unfit for use in the Mikdash or in conjunction with terumah or kodshim.

“There are over ten sources of tumah, including a corpse of a human, animal, or a sheretz,” Rabbi Orzel explains, holding up a mouse as a visual aid. “A live person — for example, a metzorah or yoledes — can also be the source of different types of tumah.” Tumah, however, can only originate from a living organism, so in order for the pure olive oil to have become tamei, it must have been exposed to a source of tumah.

“The easiest method of transmitting tumah is by maga, touching. And that’s why we tend to picture all those Yevanim going around opening all those pure bottles of oil and touching them,” Rabbi Orzel continues. “But this kind of activity wouldn’t really matter, because min haTorah, only a Jewish body, which has instrinsic kedushah, can become tamei and subsequently ‘contaminate’ other people and items. So that means that despite all his evil intentions, that Yevani soldier didn’t have sufficient kedushah-value for tumah to have any effect. He could have touched as much oil as his heart desired, but it would still remain tahor.”

A corollary to this idea — and necessary to decipher the oil mystery — is how different materials “conduct” tumah.

If a vessel is made of gold, silver, or any other metal, the source of impurity need merely touch the outside of the vessel and it will transmit tumah to its contents. An earthenware vessel, however, functions differently.

“In most cases,” he says, “earthenware can be treated more leniently than other materials, in what we’ll call ‘external immunity.’ This means that if the pitcher was touched by an impure person (or neveilah) on the outside, it does not become tamei. Neither the vessel itself, nor its contents, will be rendered impure. Contamination is only possible through the inside.”

But there is also a stringency, Rabbi Orzel explains, as he lifts his mouse by the tail. “Inside an earthenware vessel,” he says, “impurity can be transmitted through the air alone.” He dips the nose of the mouse into an open earthenware vessel, careful that it has no contact with either the rim or the contents. “The tumah would then ‘fly’ though the air inside the keli and render it a primary source of tumah. The contents will, in turn, be considered a secondary source of tumah, again, through the air.”

With these basics in mind, we can reconsider the olive-oil conundrum. How did the Syrian-Greeks contaminate the pitchers if their gentile bodies could not transmit impurity?

Rabbi Orzel offers two solutions:

“One answer suggested by some is that the Yevanim took a k’zayis of dead sheretz, neveilah, or meis, and touched it to the outside of all metal vessels.” Rabbi Orzel demonstrates as he taps a neveilah meat sample on some metal pitchers he has arrayed on the table in front of him. “And in the case of the earthenware keilim, they had to break the seals, lift off the lids, and suspend the source of tumah in the air inside.”

An alternate suggestion is that, as Rabbi Orzel says, “These Yevanim were learned reshaim. Aware that they could not ritually contaminate the oil themselves, but determined to extinguish the holy light of the Menorah, they engaged the services of their newly acquired Misyavni (Hellenist) friends.”

These were Jews who had abandoned their heritage and adopted the Greek customs, language, and culture of the day. Part of their disdain for Jewish practices meant neglecting their tahor status, and so these impure Jews made sure to come into contact with all the tahor oil they could get their hands on. “These Jewish traitors would touch metal keilim on the outside and the earthenware keilim on the inside, transmitting the impurity from their bodies to all of the oil, therefore rendering it tamei.”

Moving On

That, says Rabbi Orzel, might be how we can explain the verse, “V’timu kol hashemanim” — how the Syrian-Greeks defiled all of the oil. But what about the next part of the verse, “U’minosar kankanim, naaseh nes lashoshanim” —how one single pure jug of oil remained to be discovered.

So far, says Rabbi Orzel, we’ve discussed the transmission of tumah via touch. But there is one other method of tumah transmission: Carrying or moving.

“Once on a hike, I came across a sheep,” Rabbi Orzel relates. “It was lying on the ground, obviously dead, and for me it was an opportunity to examine the split hooves without any resistance. I carefully lifted the sheep’s leg with my hiking boots, relishing my front-seat view of the hooves. After I had walked on, abandoning the sheep, I realized that had I been on the way to the Beis Hamikdash and related my experience upon arrival, they would show me the door in no uncertain terms. ‘You can’t come in today. You’re tamei. Even an immediate dip in the mikveh won’t help you. Your impurity continues after immersion, until evening.’

“Even if I could argue back that I had specially avoided touching the carcass, they would gently point out that I had become tamei via something called ‘tumas masa’ or ‘hesat’ — tumah transmitted by carrying or moving. Because I moved the leg of the sheep, this rendered me impure.”

Rabbi Orzel recounts how, on another occasion, he visited an abattoir, and was obliged to pass through a room that was packed with suspended pig carcasses. While he squeezed his way along the wall, he unwittingly moved one of the slaughtered pigs. “Once again, I was contaminated with tumas neveilah via masa,” Rabbi Orzel relates.

“Now,” he continues, “assuming that you don’t have the hobby of playing with dead animals and you don’t make it a practice to walk through abattoirs stuffed with hanging carcasses, is it safe to assume that you were never ‘nosei es haneveilah’? Believe it or not, you probably were.”

Rabbi Orzel can’t resist pulling out a mini-shopping cart. “Have you ever been shopping in a non-Jewish supermarket? You’re filling up your cart, minding your own business, and as you turn a corner, you accidentally bump into another cart, which contains a package of non-kosher meat. Your inadvertent moving of the meat by pushing the cart it’s sitting in has actually rendered you a ‘nosei es haneveilah’ and consequently, tamei.”

Returning to the events of the Chanukah miracle, what do the halachos of “masa” have to do with the little jug found by the Chashmonaim?

One Hidden Jug

There is a special set of halachos that apply to someone rendered a zav (a man or woman who’s had a certain discharge), where the halachah of masa also applies. That means that if one carries, moves, or bumps into a zav, that person becomes tamei. In addition, any item the zav carries or moves becomes tamei as well.

“A zav can walk the streets, pushing people right and left and center — even with an intervening stick — and they will become tamei,” Rabbi Orzel explains as he lifts up a wooden rod and jabs his selection of pitchers in turn.

What’s more, he says, the stringent laws of zav nullify the “external immunity” of an earthenware vessel, which means that a zav who taps a clay jug with his stick (which is not mekabel tumah in its own right) renders it, and all of its contents, tamei, similar to the way a metal vessel receives tumah from the outside by a mere touch.

With all these possibilities, does Rabbi Orzel have his own theory as to which type of tumah contaminated the pitchers?

“Well, we really don’t know,” Rabbi Orzel admits. “Were the Misyavnim — the Jewish Hellenists who, unlike the gentile Greeks, could be tumah carriers — temei’ei meis or temei’ei sheretz? Zavim or metzora’im? What we can safely suspect is that they carried the most stringent (and common) type of tumah — tumas zav.

There is yet another reason to consider that the oil had been defiled by tumas zav. “True, min haTorah a non-Jew can’t become tamei,” Rabbi Orzel says, “but at some point the Chachamim decreed that all non-Jews and amei ha’aretz be considered zavim.”

If this condition rendering non-Jews zavim had already been enacted by that time, then every Syrian-Greek coming into contact with the oil jugs could in fact render those jugs tamei, without having to utilize their Jewish Hellenist counterparts. And even the most hermetic seal of the greatest Kohein Gadol would not be able to prevent the contents from becoming tamei.

“If so,” asks Rabbi Orzel, “how could any of the jugs of oil still be tahor? How could the Jews be sure it wasn’t moved, even if the seal wasn’t broken?”

Rabbi Orzel answers his own question, quoting a Tosafos suggesting that the pitcher was partially buried in the ground. The Jews who discovered it could see that it hadn’t been moved, so there would be no issue of tumas zav, and the seal of the Kohen Gadol would still have been necessary to ensure that the origins of the oil were pure.

Another possibility relates to the unusual shape of the jug. There is a certain leniency learned from the pasuk in Sefer Vayikra that discusses breaking any earthenware vessel a zav touches. Rabbi Orzel explains: “It comes to teach us a special leniency in ‘hesat hazav,’ something that a zav moved. What he moved can only become tamei if he can also actually touch the inside of the vessel. But if he can’t possibly reach the inside of the vessel, then moving it won’t make it tamei either.”

What, then, is the implication for our lone pach shemen?

“It then follows, that if this earthenware jug had a very tiny opening, just enough to let the contents in and out but not wide enough for a human finger,” Rabbi Orzel says as he holds up a vase with an extremely narrow neck, “hesat hazav will no longer be relevant. If a zav could not have feasibly inserted his finger and touched the inside of the vessel, then even if he moved the outside, if would not have made the contents tamei. Therefore, if the discovered oil — with the seal intact — was stored in an earthenware jug with that remarkable design, it must have been one hundred percent tahor.”

Could all this serve as a clue as we try to visualize the horror of destruction and the miracle of salvation against all odds, knowing that the same Divine protection that brought salvation at the time of the Maccabees repeats itself in every generation?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 839)

Oops! We could not locate your form.