Numbered Days, Immeasurable Life

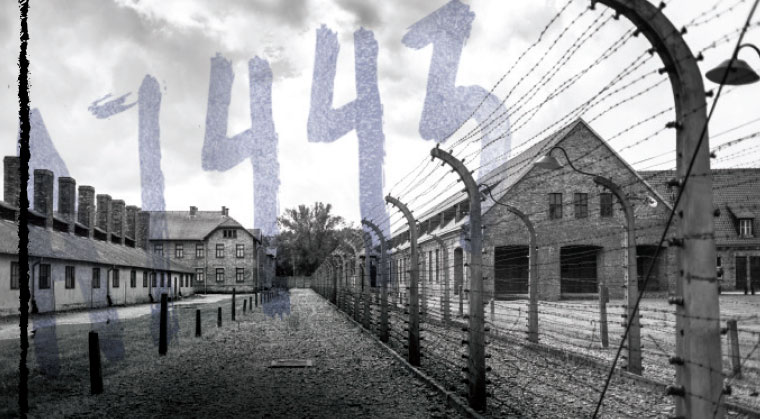

The bluish numbers on Itu Lustig’s arm read A7443 even 74 years later. It took over 50 painful pricks of a needle for the Nazis to tattoo them there. It wasn’t until Itu had grandchildren that one of them thought to sum the numbers together. “They add up to 18, chai,” she says in a tone of wonder.

“I often asked myself why I kept going during the war,” she says. “I was starving, filthy, miserable. Why should anyone want to go on?” She sweeps an arm toward a buffet crowded with family photos. “When I look at all this, I understand why I had to go on.”

Smiling from the photos are her three children, who produced well over a dozen grandchildren and many great-grandchildren. Itu, now 89, became a great-great-grandmother not long ago, and her family has brought her much nachas. Mrs. Lustig herself was honored four years ago for her 40 years of leadership with the Crown Heights Bikur Cholim.

Itu Lustig is a true survivor. Despite her trauma, despite the nightmares that required her husband a”h to shake her and reassure her, “It’s over, they’re not here anymore,” she did not give up or retreat into depression. Instead, she founded a family and leads a full and productive life, taking revenge on the Nazis by contributing to the rebuilding of Klal Yisrael.

We meet in her spotless, simple home in Crown Heights. It’s a chilly day for June, so she wears a soft, gray cardigan and pearl earrings that compliment her short blonde sheitel and intelligent blue eyes. Mrs. Lustig has a quiet dignity, but she’s not shy; several times a year, she tells her story to groups of students and kiruv recruits. “I don’t have to prepare,” she says, tapping her head with her forefinger. “It’s all up here. Maybe I think if I tell it over enough the younger generation will understand it was real!”

Life, Interrupted

Mrs. Lustig recalls an idyllic childhood in Strâmtura, a small, rural town in Romania with about 100 Jewish inhabitants, plus another 100 in the town’s yeshivah. “It was very primitive,” she relates. “We had no electricity or indoor plumbing. Our transportation was horse-and-buggy. But it was very pleasant.” The family lived in a house with a large yard and grounds beyond; in the summer, they swam in a nearby river. They kept their own cows and chickens, grew their own vegetables, and gathered all sorts of berries and fruits from the vines and trees on the property. “Apples, pears, plums — every fruit except bananas,” she says. “I never tasted a banana till I came to the US.”

Her father, Rabbi Tzvi Hirsh Kahan, a Vizhnitzer chassid, was the rosh yeshivah. There was no Bais Yaakov in town, so she attended public school, and someone was brought to the house to teach the girls to daven. The rest, she says, “we learned from our mamas and grandmas.”

Since the town was so isolated, they had no access to radio or newspapers — and so they didn’t know much about what was happening in the larger world. In 1940, however, their formerly Romanian village was transferred to Hungarian control, a reward for Hungary joining forces with the Germans. Suddenly, Itu was barred from attending school, and Jews weren’t allowed to operate businesses. They survived by helping each other; those with grocery stores would make their merchandise available to others, those with crops shared produce. For the next few years, life continued in this way, with the Jews otherwise left to their own devices.

All that changed in 1944, when the Germans took over. “On the very first day, they arrested my father and the town shochet,” Mrs. Lustig recounts. “They took him away, we had no idea where. It was right before Pesach, and my mother had just given birth to her seventh child two weeks before.”

(Excerpted from Family First, Issue 601)

Oops! We could not locate your form.