Not Just a Malach

In Yiddish ah yohr mit ah yoiveil connotes a very long period of time. But a literal yoveil — 50 years — is long enough in itself and this year on the second of Kislev it will indeed be the proverbial yoveil shanim since that giant of American Torah Jewry Rav Aharon Kotler ztz”l left the world.

In Yiddish ah yohr mit ah yoiveil connotes a very long period of time. But a literal yoveil — 50 years — is long enough in itself and this year on the second of Kislev it will indeed be the proverbial yoveil shanim since that giant of American Torah Jewry Rav Aharon Kotler ztz”l left the world.

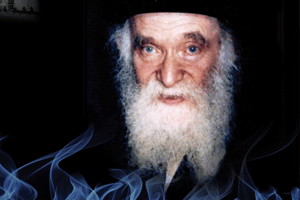

I’ve come to speak with Rav Yechiel Yitzchok Perr, a close talmid of the Rosh Yeshivah from Lakewood’s early days, who himself went on to teach countless talmidim at Yeshivah Derech Ayson, which he founded many decades ago in Far Rockaway, New York. Rav Perr arrived at the Lakewood yeshivah as a 21-year-old in 1956 and remained there for seven and a half years. During those years, its student body was comprised of only 70 to 80 bochurim, enabling him to take full advantage of the opportunity to draw close to the gadol hador.

By the time Rav Aharon arrived on these shores in 1941, he had already gained renown as a leading figure of the Torah world — first in Slutsk, where his father-in-law, Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, headed a major yeshivah, and later heading his own yeshivah in Kletzk. After his frenetic wartim e efforts with the Vaad Hatzalah to rescue Jews from Nazi Europe, Rav Aharon focused his brilliant mind and boundless energies on building Torah in the country to which Divine Providence had seen fit to send him.

Rav Perr sits with a small blue loose-leaf notebook containing hundreds of entries detailing stories or conversations involving Rav Aharon that he personally witnessed or that he heard from someone else who did. And that, too, is something he learned from his rebbi. “The Rosh Yeshivah was known as a very big baki in stories about the Vilna Gaon. He once told me that everything he knows about the Gaon he received personally from the Chofetz Chaim, who first came to Vilna as a 17-year-old bochur. This was only 47 years after the Gaon was niftar. Everything the Chofetz Chaim knew about the Gaon, he heard from someone who knew it firsthand from the Gaon, or from someone who heard it from someone who knew it firsthand. I once told this to Rabbi Samson Rafael Weiss, who said it can’t be, because the numbers don’t add up. After he said that, I stopped quoting the number ‘47 years’ when telling this over.”

But one day, Rabbi Yehoshua Kalish, a rebbi in the Yeshiva of Far Rockaway, showed Rav Perr a copy of the New York Times story of September 16, 1933, on the Chofetz Chain’s petirah, which reported that the family said he was 105 years old. Based on that, he would indeed have been 17 years old exactly 47 years after the Gaon’s petirah. The Rosh Yeshivah, as usual, had been exactly correct.

It’s not only the veracity of specific stories that matter deeply to Rav Perr, but also a correct understanding of what made Rav Aharon such a larger-than-life presence and enabled him to chart the direction of the American frum community for generations to come. “The most amazing thing about him was that he was not an orator. He spoke a very difficult-to-understand Yiddish, a Russishe Yiddish. His talmidim, most of whom were native English-speaking boys, would teach each other that, for example, the word ‘geconchet’ that he used meant ‘ge’endigt’ [finished].

“Furthermore, when he spoke before a microphone, he would shuckle to and fro, so that half the word would be picked up by the mike and half of it would fade out. And with a lot of words, it was very hard to pick up altogether; it took me many years to figure out that when he said ‘stayt, stayt,’ he meant ‘ihr farshtayt.’

“And when he’d say a vort, he didn’t elaborate or illustrate it, as others would have done. He said his vort, and that was it. So we wonder: How is it that his ideas came to wield such influence? Now, it’s true that those people who could understand him were so impressed that it created a widening circle of reverence that, in turn, impressed still others. A person like Irving Bunim, for example, was very deeply impressed by him and was able to convey that to others.

“Still, what was the essence of his power, his chiddush? People say ‘Torah lishmah.’ But that’s not true, because all the gedolim who came over from Europe were lishmah Yidden, and yet they didn’t have the impact he had.”

For one thing, Rav Aharon was on fire for Torah; he was, as Rav Perr puts it, “not just a malach, but a saraf.” That fire burned brightest when Rav Aharon gave shiur, during which his face literally shone. And when he finally came to the point he wished to make, he was suffused with excitement and joy.

In the summer, the first part of the shiur would be on Shabbos afternoon and in the winter on Motzaei Shabbos at 8 p.m., with a continuation on Monday morning. Then he would travel into Brooklyn, where he and the Rebbetzin lived, until Thursday or Friday, when he would return to the yeshivah for Shabbos.

The shiur was famously complex, an exquisite, multi-stranded intellectual structure that dazzled the listener as much with its impeccable logic as with its breadth. But who understood it? “The problem,” says Rav Perr, “wasn’t understanding the shiur, but following it through all its twists and turns,” and being able to absorb all the information that, in the course of just an hour and a quarter, Rav Aharon would deliver rapid-fire “like a machine gun.” Many bochurim could follow generally where Rav Aharon was going with the shiur, but it was only the select few who grasped it completely. But whether or not a bochur was in the first group or the second, he came away with an understanding of how much one has to know, “that it’s not enough to throw out a few sevaros and you’re done for the seder.”

Who followed the shiur in its entirety? Rav Perr says that Rav Meyer Hershkowitz surely did. And once, when the Rosh Yeshivah had learned that a certain rav refused to make an appeal for the Lakewood yeshivah, he wondered aloud, “Who has talmidim like ours?” and he began listing off his best talmidim, Rav Perr remembers. “The first name he mentioned was Rav Yosef Rosenblum. I don’t recall the whole list he made, but I’m sure Rav Yitzchok Feigelstock and Rav Shmuel Feivelson were on it too.”

And then there were the “chozrim,” those bochurim who didn’t take notes at the shiur, since it was on Shabbos afternoon, yet stood up after Shabbos and said over the shiur with precision. Rav Perr recalls one of them, Reb Meir Hartstein, as a “quiet person who is still sitting and learning, and who used to say over the shiur as if he were a tape recorder.”

Preferred Seating

Rav Aharon’s fire burned as brightly outside the beis medrash as it did within. Rav Perr recalls with fondness the scene at the Shabbos meals, which became de facto learning sedorim as well. “About 15 bochurim sat at the Rosh Yeshivah’s table, which was by invitation only; when one of those at the table got married, another bochur would be invited to join the group. For much of my time in yeshivah, I had the zchus of sitting right opposite him, face to face. Since I didn’t get married so quickly, I was at that table for many years.

“So he sat at the table surrounded by bochurim on all sides,” Rav Perr continues, “and there’s something we bochurim didn’t even realize until it was pointed out to us by an older rav who was visiting for Shabbos. Everyone was firing questions at the Rosh Yeshivah. If a bochur was learning Kodshim, it would be questions in Kodshim. Someone else would be learning Moed, so he’d ask from there. Some bochurim were still learning the yeshivishe masechtos and they’d ask him from those places. Yet others would ask halachah questions — the Rosh Yeshivah was a big posek in halachah — and he would answer everything. And these weren’t general questions, but rather diyukim like, ‘Rashi on daf zayin uses such and such a lashon, but it’s shver.’ So this rav is sitting there and he says to us, ‘Rabbosai, do you see what’s going on here? You’re asking from every part of Shas and he’s answering kil’achar yad [effortlessly].’ He was right, but it never occurred to us. We figured you just asked and you got an answer.”

Rav Aharon would sometimes take a break from the back-and-forth in learning at the table to ask the bochurim to sing some zmiros. He loved niggun, although he himself didn’t have singing ability and would not even daven for the amud on the Shabbos before he observed a yahrtzeit. One niggun that was particularly meaningful to him was “Lulei Soras’cha.” Rav Perr treasures the memories of being at a sheva brachos or a mesibah in the yeshivah, when the Rosh Yeshivah would scan the crowd looking for him and then, spotting him, give him the sign to begin his cherished “Lulei Soras’cha,” which really bespoke his indescribable attachment to Torah. David HaMelech says “lulei soras’cha sha’ashu’oy, az avadti b’onyi” — were it not that Your Torah is my delight, I would be lost for my suffering. Rav Menachem Perr ztz”l, Rav Yechiel’s father, who was a contemporary of Rav Aharon in the Slabodka yeshivah, told his son that during World War I, even the rumble of the approaching cannons could not distract Ar’ke Suslovitzer — as Rav Aharon was then known — from his intense concentration on his learning.

All His Children

The Rosh Yeshivah’s fire not only illuminated; it also warmed. “The way he cared about his talmidim was amazing. I heard from Rav Yitzchok Feigelstock that when Rav Aharon was very sick in the hospital before his petirah, he was busy trying to find a shidduch for a certain talmid. You must remember that shidduchim were very hard to find in those days; very few girls wanted to marry a yeshivah boy. Reb Yitzchok said to me, ‘Look what the Rosh Yeshivah was thinking about as he lay in the hospital — about a shidduch for so-and-so, even though that fellow vet nisht entferen kein shvere Rambams [i.e., he wasn’t one of the stronger talmidim].’”

The caring he showed his students was grounded in a belief that true happiness and success were to be found in an embrace of Torah, and only Torah. To explain, Rav Perr relates a story that, he is careful to point out, he only heard fourth- or fifth-hand. Nevertheless, he says, anyone who knew the Rosh Yeshivah could see that it could have indeed happened. “There was a bochur who came from Europe in the late 1940s and had lost everything in the war. Such a person is barely alive, a hollow shell, and dead inside. All that was still alive inside was his rebbi, Rav Aharon Kotler, by whom he had learned in Kletzk. And he came to Rav Aharon and said, ‘Rebbi!’ Rav Aharon said to him, ‘Vu haltst du in lernen?’ This man had wanted to cry out his whole heart and kishkes over what had befallen him, but all Rav Aharon said to him was ‘Vu haltst du in lernen? Nemt zich tzum lernen’ [Where are you holding in learning? Begin learning].

“About six weeks later, Rav Aharon sat down next to this fellow on a bus traveling to New York. He turned to him and said, ‘Yetzt dertzayl mir dayn geshichte — Now tell me your story.’ When I heard this story, it made me cry, but it has to be correctly understood: There is nothing that can help such a person, nothing. There’s no use in telling his story. I never heard the word ‘Holocaust’ from Rav Aharon. He didn’t talk about it, it was too much. What’s left? Learn. Learn Torah, warm up your heart a little bit. Bochurim would come to him with problems, and he would say, ‘Sit down and learn.’ There was no solution; the solution was ‘learn.’”

Rav Aharon’s relationship with his boys was one of mutual esteem. He appreciated their willingness to go against the tide of American society to learn Torah and they revered his towering greatness and rapturous love of Torah — and they too felt his love for them. Rav Perr shares an insight that he heard from someone who didn’t know Rav Aharon personally, but observed him from afar. “He said the others were afraid of America, but not Rav Aharon. He liked American bochurim. You have no idea how turned off Europeyishe Yidden in general were from the ‘yoldishkeit’ of American bochurim, so untutored, so unpolished. Fellows with beards could talk to a rosh yeshivah like one talks to a storekeeper. I saw someone talking to Rav Aharon with his foot up on a chair. But the Rosh Yeshivah was not concerned with these things, just Torah, Torah, Torah.

“Many who were in Lakewood in my time were there because they’d fought to be there,” says Rav Perr. “The Rosh Yeshivah came to America to sell an idea — full-time involvement in Torah — that nobody subscribed to. The rabbanim were against him, the parents were against him as if he were ‘kidnapping’ their kids. But the youngsters came to him on their own. A young man told me the following story about himself. He lived in Boro Park and as an 18-year-old he met the Rosh Yeshivah there. At that time this young man was wearing purple pants, sporting a double-decker tchup of hair, and he said, ‘I want to come to the yeshivah.’ The Rosh Yeshivah said, ‘I have to farher you,’ but the fellow said, ‘You can’t farher me. I don’t know anything.’ The Rosh Yeshivah said ‘Du vilst lernen? [You really want to learn?]’ and he answered, ‘Yes, I want to learn.’ So the Rosh Yeshivah told him to come. He sat and learned for many years, even continuing in kollel, which was rare in those days.

“This fellow was a yasom, the only child of a refugee mother. The Rosh Yeshivah wanted the bochurim to be in yeshivah for Rosh HaShanah, but his mother called him up to come home. She cried to him on the phone, ‘Vos fahr a yontiff vet zayn ohn dir, vemen hob ich? [What sort of Yom Tov will it be without you; whom do I have?]’ So he got on the bus and went home. He’d only been home for a few minutes when the phone rang — it was the Rosh Yeshivah calling to speak with his mother. She took the phone, and spoke for just a few moments. The son heard her say, ‘Ich herr, ich herr [I hear, I hear].’ She hung up the phone and told him, ‘Go back to yeshivah.’ He asked her what the Rosh Yeshivah had said, but all she said was, ‘I didn’t understand what he said to me, but you have to go back to yeshivah.’ When I think of this story I want to cry for the tzaar of that mother, but the Rosh Yeshivah was making bnei Torah even out of boys wearing purple pants, and you’re not going to be a ben Torah unless you daven in the yeshivah on a Rosh HaShanah.”

When Rav Perr first came to yeshivah, he already had a close connection to Rav Aharon because of his father, whom the Rosh Yeshivah regarded as a tzaddik; Rebbetzin Kotler would regularly seek his brachos. Rav Perr recalls with a smile that when he was in the midst of the shidduch with his wife, a granddaughter of Novardoker Rosh Yeshivah Rav Avrohom Yoffen — a shidduch that was redt by Rav Aharon himself — Rebbetzin Yoffen called up Rebbetzin Kotler to ask about him. The latter said, “His father is such a tzaddik, so exceptional.” To which Rebbetzin Yoffen responded, “That may be, Rebbetzin, but what’s with the bochur?”

Rav Perr also became the talmid to whom the Rosh Yeshivah would turn for English translation work, which he frequently needed. “I once translated an article for him. I don’t recall if I had first shown him the article or maybe he had shown it to me. It was written by a leading Modern Orthodox rabbi of the time and appeared in a law school journal containing essays by religious leaders on how their communities deal with various contemporary problems. The head of the Archdiocese took all the strong Catholic stands about life, etc., the Protestant representative wrote about all the human problems created by immorality, and the rabbi, in a gross misrepresentation of the Torah’s views, took a lenient view on almost everything.

“I reviewed the article and went to the Rosh Yeshivah’s room to report my findings. I knocked on the door and heard him say ‘arein.’ I told him what I had found, and the Rosh Yeshivah got so heated he started verbally firing away: ‘S’iz sheker, s’iz khozov, s’iz farkert fun di Gemara [It’s false, it’s the opposite of what the Gemara says].’ Taken aback by his intensity, I said, ‘Ich farshtay, ich farshtay [I understand].’ But he grabbed me by the lapel and, looking straight up at me, eyes ablaze, he started shaking me: ‘S’iz shkorim, s’iz kefirah! [These are lies, this is heresy!]’ And I started wondering to myself, Does the Rosh Yeshivah think I’m the one saying these things?

“Today I realize that he wanted to kasher me with his ros’chin, with the holy fire of his recoil, his indignation. I had been reading this stuff and, willy-nilly, there’s a bli’ah, a modicum of absorption of the poisonous kefirah, and there’s nothing like the kana’us of the Rebbi to remove those absorbed toxins.”

Once, Rav Aharon called his “English specialist” in on Erev Yom Kippur and asked him to send a telegram to a certain individual, a prominent rabbinical figure in America. He dictated the text: “Hareini mocheil lichvodo mechilah gemurah, v’im mar haslichah [I hereby forgive you completely, and the power to forgive is yours]. Gmar chasimah tovah, Aharon Kotler.”

Rav Perr wrote down the text and then said, “The Rosh Yeshivah should forgive me, but why does he have to write ‘v’im mar haslichah’?” Rav Aharon got very agitated and said, “I tell you, I did nothing to him, and he attacked me and humiliated me in public!” Rav Perr tried again: “So aderaba, since the Rosh Yeshivah did nothing to him, why should he write that, which makes it sound like he wronged this man somehow?” Then, with characteristic humility, Rav Aharon said softly, “But it’s Erev Yom Kippur. Who can know?’”

The Rosh Yeshivah would also occasionally send Rav Perr to speak at fundraising events for the yeshivah. “Once,” Rav Perr relates, “I told him I have aimsa d’tzibbura [fear of the audience]. So he told me the story of someone who had a lion that he would take around and people would pay to see it. One day, the lion died, so he hired a Yiddel to dress up like a lion and jump around in the cage and make kolos. One day, he’s jumping around and the door to the cage opens and in comes a lion. The Yid takes one look and cries out in fright ‘Shema Yisrael!’ to which the newly arrived lion responds ‘Baruch Sheim!’ He laughed heartily at the vitz and said to me, ‘You say you have fear of them, but they’re even more afraid of you.’ When I spoke there, I told the story and added, ‘I assume that you’re afraid that I’ll speak long. But don’t worry, I’ll speak briefly.’”

If Rav Aharon’s whole world revolved around Toras emes, it’s only natural that a defining trait of his was a commitment to emes whatever the cost. “If you left the kollel, he paid you up what he owed you. Others didn’t do that, not because ‘I don’t owe you’, but because it was understood that they didn’t have the money and if you’re no longer here, you don’t get paid. In Lakewood, kollel pay started one week after sheva brachos; the Rosh Yeshivah said the first week was on the shver. But if you left and he owed you a thousand dollars, you knew you could borrow against it because he was going to pay you it all. He once had a meeting with rabbanim in the Bronx about raising money for the yeshivah and he said to them in a moment of passion: ‘Vos tuht ihr fahr eiyereh balabatim? Ihr zogt far zei drashos? Nemt bei zay a bissel gelt far Toyrah, vellen zei hobben Olam HaBa far dem. [What do you do for your congregants? Tell them drashos? Take a little money from them for Torah and they’ll get Olam HaBa for it.]’ And they were all so angry at him! But he had this inconvenient tendency to say the truth.”

On a lighter note, Rav Perr was once with the Rosh Yeshivah when someone asked him his age because he said he wanted to give “chai dollars” to the yeshivah for every year of the Rosh Yeshivah’s life. The Rosh Yeshivah smiled and said, “Oyb azoy darf men takeh zog’n der emes [If so, then I really must tell the truth].”

The Bigger Picture

Lakewood is, of course, synonymous with Rav Aharon Kotler, but it wasn’t his only horizon. “It was his main focus, but in a larger sense, all of Klal Yisrael was his focus,” says Rav Perr. “I remember when a Conservative congregation started in Lakewood; its building is now one of the Lakewood batei medrash. Now, the yeshivah’s baal korei, Rav Avrohom Kushner, used to call Rav Aharon up with ‘Yaamod Moreinu v’Rabeinu,’ but then one day, he called the Rosh Yeshivah up with ‘Yaamod Harav Aharon ben Harav Shlomo Zalman, shlishi.’ I’m a curious person, so I asked him, ‘Avrohom, how come you called the Rosh Yeshivah up by his name all of a sudden?’ He said, ‘The Rosh Yeshivah called me in and told me to start calling him up that way. I asked him why and he told me that he heard that by the Conservatives, which were then located a few blocks away from the yeshivah, they call people up without names — yaamod shlishi, ya’amod revi’i and so on — so he wants to be called up by his name.’

“And I thought to myself, with the typical cynicism of a 20-something Amerikaner, ‘Does the Rosh Yeshivah think he’s going to be mashpia from this little yeshivah on the Conservatives, who are going to continue driving their cars to shul on Shabbos anyway? But after the proverbial 40 years that it takes to begin to understand one’s rebbi, I realized: Who knows how some of his talmidim would turn out, and whether they’ll bring proof from the fact that Rav Aharon, too, was called up without a name, and who knows what other changes they’ll justify with that?”

Rav Aharon’s other response to the Conservatives opening a house of worship in town was to call in Rav Perr and Rabbi Chaim Zelikovitz and a few others and tell them to start learning with Lakewood balabatim. Rav Perr initially balked at the idea because it would interfere with his night seder, but the Rosh Yeshivah insisted and he acquiesced. “Later,” says Rav Perr, “there was this very frum bochur who came over to me and said, ‘You should know that you are oiver many issurim d’Oraysa every time you teach a class because you’re teaching them Torah and they’re not making birchos haTorah.’

“I said to him, ‘You know what? I’m going to ask the Rosh Yeshivah, he’s the one who told me to do it. So I went and asked Rav Aharon. He got very upset: ‘Vos fahr a shtus un a hevel i’dos? M’vil mekareiv zayn a yid un m’zogt em, “Herr tzu a minut, ich vil dir eppes zog’n, ihr darf friyer machen birchos haTorah”? [What kind of foolishness is this?! You want to draw a Jew close and you have to tell him, “Wait a minute, you first have to make birchos haTorah”?!]’”

Rav Aharon’s concern for others’ spiritual welfare extended beyond his students, to every other Jew. “When I came to Lakewood, I found out that you’re supposed to take a haircut by a fellow named Mr. Meckler,” Rav Perr remembers. “Who was he? The Rosh Yeshivah had met Mr. Meckler on the bus to Lakewood and in the course of their conversation, Rav Aharon learned that he was not at that time a shomer Shabbos. He said he has to work on Shabbos for parnassah. Rav Aharon then asked him what else he could do and Mr. Meckler told him that he was an expert barber. So Rav Aharon made an agreement: if he begins keeping Shabbos, he’ll send the boys to him for haircuts.

“The Rosh Yeshivah set up a barber’s chair in his bedroom and the oilam would come, sitting four or five at a time on his bed waiting for their turn. We couldn’t stand wasting the one day in the week that we had free time waiting an hour for a haircut, which in any event wasn’t very professional, to say the least. But we went because the Rosh Yeshivah sent us.”

They went because the Rosh Yeshivah’s infinite patience with them taught them, in turn, to have a bit of patience for a down-and-out amateur barber. Rav Perr notes that Rav Aharon’s own room was in the yeshivah dorm and the bochurim would often noisily carry on until very late. Yet not once did the Rosh Yeshivah ever come out of his room to reprimand the boys or quiet them down. Musing about this a half-century later, Rav Perr reflects: “I suppose he just loved his talmidim. Just like we all do.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 434)

Oops! We could not locate your form.