No Greater Treasure

| September 20, 2022“He would be killed just for having it in his possession. But a Torah is a Torah and my father was determined to save it”

As told to Sandy Eller by Rabbi Benzion Katz

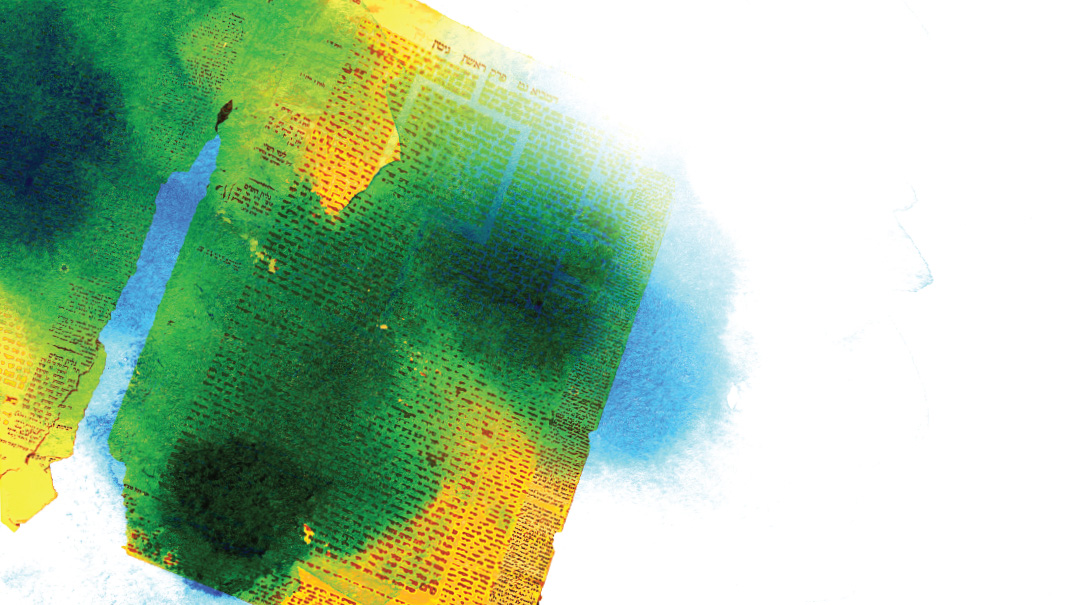

IT measures just 15 by 10 inches, is over a century old, and has been part of the fabric of my life since before I was born.

It is the sefer Torah that my father rescued from the depths of a World War II work camp during one of the darkest times known to humanity. Whose it was and where it came from is a mystery. But what happened to this priceless treasure since then is a story that bridges the gaps between the past, present, and future, links in a chain that can never be broken.

My father, Reb Yehoshua Alter Katz, grew up in Apsha, Czechoslovakia, a small town near the Romanian border. He would tell me how his father, whose name I bear, was so wealthy that they once took a 15-minute train ride through the Czechoslovakian forest so that my zeidy could show my father how he earned his parnassah.

“You see the forest we crossed on the train?” my grandfather asked my father. “All those trees, all that lumber belongs to me. And the train? That’s mine too.”

My parents met before the war and were engaged for six years. My mother came from the Hungarian town of Nanash, and she and her family were taken away to Theresienstadt, the “model” concentration camp, where they all survived. I still have the siddur my father gave my mother as an engagement gift — it has a Hungarian translation and is well over 70 years old.

But while my mother and her family fared relatively well during the war, my father was sent to a Hungarian work camp whose name he never shared with me. Although the conditions and work were brutal, he and his fellow workers weren’t living in fear for their lives. But all that changed on the day that my father found a small sefer Torah in the camp among a pile of seforim strewn across the floor.

He had no idea who it belonged to, but he knew that it would be destroyed if it was discovered by the guards. He also knew he would be killed just for having it in his possession. But a Torah is a Torah and my father was determined to save it.

The first part of my father’s plan was relatively simple. Since there was no way to get the Torah out of the camp, he disassembled the entire sefer, separating each piece of klaf. Smuggling the pieces out was more complicated — no one was allowed to take anything out of the work camp, so one wrong move would mean the end of his life. My father carefully wrapped pieces of klaf around his body, a few sections at a time, hoping they would go unnoticed under his clothing, and smuggled the entire sefer out over the course of a few days. He even managed to sneak the atzei chaim out of the camp by sticking them inside his socks.

Twice, the guards decided to check the prisoners as they left to make sure they weren’t taking any tools or valuables with them. My father was terrified and sweating heavily as one by one, the prisoners were inspected and sent to a new line once they were cleared to leave. The first time it happened, my father managed to sneak over to the approved line without being seen. The next time, a flash of lightning had the guard in charge looking away for a split second and my father jumped onto the other line, evading inspection.

My father buried the Torah next to a tree. He carved a mark into the bark, hoping to be able to locate it again one day. After the war, my father returned and unearthed the Torah, digging up the pieces one by one. Some sections were completely blank, the ink dissolved by my father’s sweat when the klaf was wrapped around his body, but my father was elated to have saved this precious Torah from the hands of the Nazis yemach shemam.

My parents were reunited after the war. I still have a copy of their wedding invitation, held at 4 p.m on a Friday afternoon, the festive seudas mitzvah taking place on Shabbos, with dancing scheduled for “bias Mashiach Tzidkeinu.” My parents traveled by ship to Eretz Yisrael in 1945 along with the Torah, and my father joined the army as he was required to, working in the kitchen so that he could ensure the food’s kashrus. He became friendly with a few people who went on to become very well known, including Menachem Begin and Rabbi Shlomo Goren, but declined an offer to become involved in the Israeli government. Eventually my father became a manager at Nesher, a cement company, and he negotiated a deal for himself that included a driver that would take him to the mikveh at Kiryat Motzkin every week before Shabbos.

My sister and I grew up in the Haifa suburb of Kiryat Shmuel, in an area known as Shikun Hachayalim. My father pieced the Torah back together and tried getting someone to restore the sefer, but he couldn’t find a sofer willing to take on such a difficult job. The Torah stayed safely ensconced in Rav Akiva Hakarmi’s shul for as long as we lived there. My father came to America in 1955 and when the rest of us followed him there two years later, the sefer Torah came with us as well. We started our new life in the goldeneh medineh in Crown Heights, with the Torah placed in the nearby Koslov shul. My father didn’t even attempt to do anything with it at that point, but everything changed when we moved to Boro Park in 1967 and my father became close with the Ungvarer Rav, Rav Menashe Klein.

A prolific mechaber seforim, Rav Klein was a survivor of both Auschwitz and Buchenwald who lost his entire family during the war. While he was honored to have my father’s war-torn Torah in his shul’s aron kodesh, he dreamed of restoring it to its former glory and kashrus. All of the sofrim Rav Klein consulted with told him it just made more sense to write a new sefer, but the idea of not fixing the Torah, despite the inherent difficulties, wasn’t a reality that Rav Klein was willing to accept. He refused to give up, even after my father was niftar in 1980. Rav Klein finally found someone willing to undertake the job, and thanks to his efforts, an Israeli sofer repaired the Torah over the course of several months.

When the Torah was completed, Rav Klein honored it by rededicating it in the shul with a seudas hoda’ah. He had tears in his eyes as he danced with the sefer Torah, rejoicing in the restoration of a Torah that, like he, had survived the worst horrors ever known. My father had risked his life to save this Torah, and it had taken more than 30 years of effort to restore it. The idea that it could be used once again by new generations was a feeling beyond compare.

The Torah is extremely delicate and we use it only on very special occasions — Yom Kippur night before Kol Nidrei, at Minchah on Yom Kippur, and on my father’s yahrtzeit, which falls out on Rosh Chodesh Tammuz. Our treasured Torah has been used at family simchahs as well — my twin eineklach leined from it at their bar mitzvah and when it was used for my grandson’s aufruf, the rav of the shul had it carried around so every person present could have the zechus of kissing a sefer Torah that had survived the war.

There is no doubt that my father had incredible siyata d’Shmaya to have the zechus of saving the sefer Torah. For me and my family, it is a privilege and responsibility to be safeguarding this precious jewel. Baruch Hashem, the Eibishter has sent me other treasures as well. Nothing I accomplish in life could possibly be as precious to me as the children my wife Yaffa and I have raised. They, and ka”h our grandchildren and our great-grandchildren, are our greatest riches. Nothing is more important than inculcating in them the lesson of my father’s mesirus nefesh and the importance of giving oneself completely for Hashem. Knowing my father was ready to sacrifice his life for this Torah is a reminder to me and my progeny of what really matters most.

Reb Benzion Katz resides in Monsey, New York, where he is an active member of Kehillas Netzach Yisroel.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 929)

Oops! We could not locate your form.