No Excuses

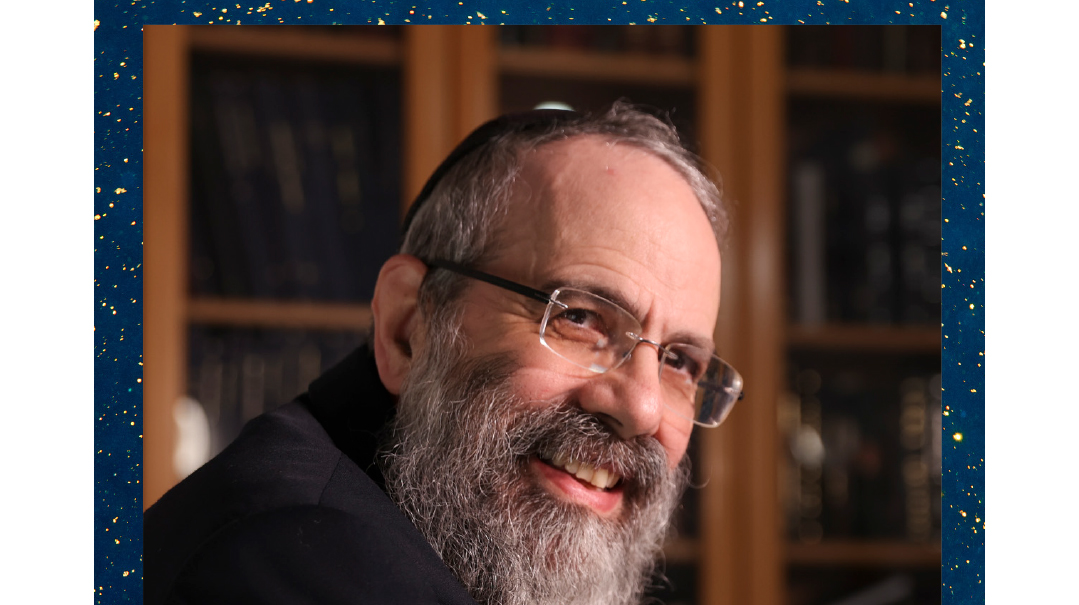

| April 8, 2025Twenty years after Rav Wolbe’s passing, his grandson reflects and remembers

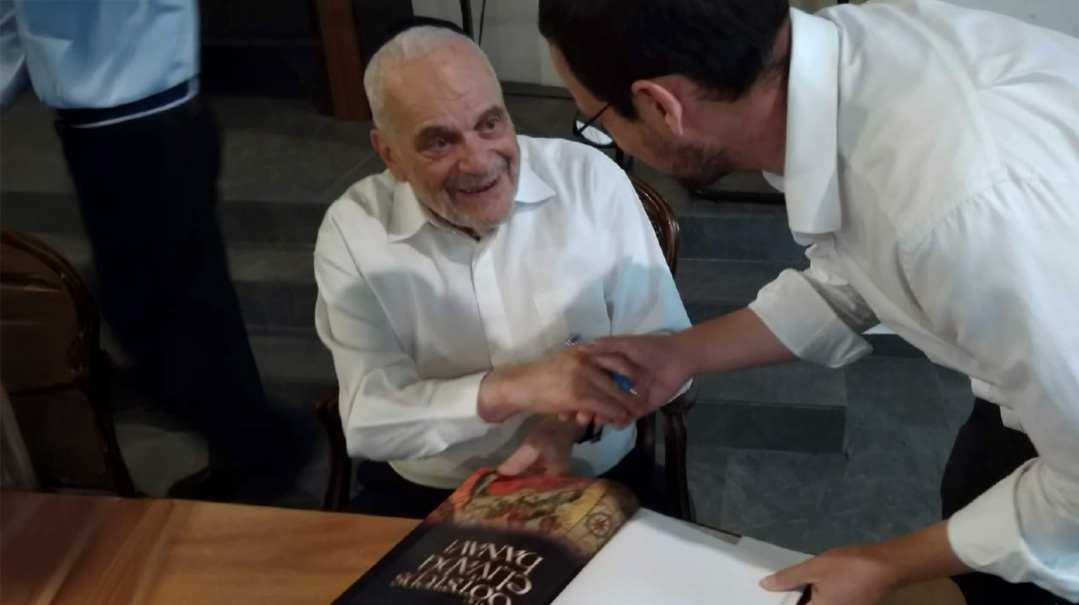

Photos: Family archives

Twenty years after the petirah of Rav Shlomo Wolbe, the Mashgiach who inspired generations to follow in the path of the baalei mussar of prewar Europe, a grandson shares recollections of an enduring legacy

It's hard to believe that it’s been 20 years since my Saba, Rabbi Shlomo Wolbe z”l, was niftar on Chol Hamoed Pesach. I spent the days preceding his passing with him in Shaare Zedek hospital, and the memories are still vivid. My grandfather never traveled with a retinue; he had no gabbai to manage his affairs or arrange “special treatment.” He shared a hospital room with two other men, with only a flimsy curtain cordoning off each patient. I was 18 then, and spent Leil HaSeder with Saba, together with my 20-year-old brother, Yoni.

We didn’t experience a traditional Seder in that sad, cramped hospital room. The only matzos we had were the square machine ones the hospital provided. We didn’t have a gleaming table at which to drink our Four Cups or ask the Four Questions, but watching our grandfather — hooked up to tubes and experiencing agonizing yissurim — was a bitter dose of maror to swallow.

At three in the morning, I helped Saba sit up in bed, hoping to alleviate his tremendous pain and discomfort. Then I sat down on the floor and asked him for a brachah. He placed his hand on my head and said, “Learn Chumash well, learn Mishnah well, and learn Gemara well.”

His levayah was twodays later. Waking up to find the whole city plastered with signs of his passing, hearing the announcements blasting from cars roving Yerushalayim, seeing tens of thousands of people converging on the Bais Hamussar that he founded, witnessing the typical jostling and jockeying for positioning at a well-attended funeral (estimates range from 35K to 100K) — it was all surreal. But the most lasting memory I have from that day happened afterward. Minhag Yerushalayim bars direct descendants of the niftar from joining the levayah procession. So while throngs accompanied Saba to Har Hamenuchos, we children and grandchildren remained in my grandparents’ apartment adjacent to the Bais Hamussar. As we reminisced about his life, my cousin, Rabbi Ahron Schwartzman, said something I will never forget.

The Gemara says that three kinds of people come to judgment in front of Hashem with excuses for why they didn’t learn. The pauper says, “I was too poor to learn.” The rich person says, “I was too rich to learn.” The person who dealt with nisyonos claims that the circumstances of his life made it impossible for him to learn. But each argument is refuted.

Hillel was poorer than any pauper and still managed to become Hillel Hazaken. Rabi Elazar was richer than any mogul, and still learned Torah all day and all night, ultimately becoming a Kohein Gadol. Yosef was subjected to the fiercest nisyonos and still became Yosef Hatzaddik. The Gemara concludes by saying: “Hillel obligates the poor, Rabi Elazar obligates the rich, and Yosef obligates those struggling with nisyonos.”

My cousin added a fourth category. Someday someone will come to Hashem, he described, and say, “I didn’t become big in Torah because I had no background in learning. I had no one supporting me. I had no rabbinic pedigree, I wasn’t trained to become a Torah scholar, I wasn’t encouraged to become big — and that is why I failed to become an adam gadol."

But the Heavenly Court’s response will be: “Did you have a weaker background than Rabbi Wolbe? Did you have more obstacles in your path to greatness than he did?”

Saba’s father, my great-grandfather, was an accomplished and learned man. He was a gifted linguist (fluent in 12 languages), a professor, historian, and author (he wrote dozens of books, including a definitive history of Jews in Berlin and Brandenburg), but hardly someone whose son would be on a path to achieve such stratospheric greatness. He envisioned his son becoming an academic or a writer, perhaps a scientist or a physician — instead he reached the apex of the Torah world.

Saba, concluded my cousin, will obligate all who claim that their background and upbringing didn’t position them for gadlus.

Journey to Greatness

My grandfather was born in Berlin in 1914. He first attended yeshivah in Frankfurt, then in Montreux, Switzerland, but in a remarkable episode of Hashgachah pratis, Saba found his way to the great Mirrer Yeshiva in Poland, to learn under the legendary Rav Yerucham Levovitz.

While he was still in Montreux, Saba heard a mussar shmuess for the first time in his life from someone who visited the yeshivah. He was so moved by what he had learned that he reviewed it excitedly with his friend. When his friend saw his enthusiasm, he told him this was nothing compared to hearing Reb Yerucham in Mir. “You should go to Mir!”

Saba was sure his father would never let, but at his friend’s insistence, he wrote a letter to his father asking permission to go learn in the Mir. To his surprise and happiness, his father agreed.

Later, his mother told him what had happened. His father, who was a somewhat superstitious man, would occasionally visit a fortune teller in Berlin. This person predicted that his son would write him a letter with a very strange request, and advised him to grant it, because it would be for his benefit. When Saba’s father got the letter asking permission to go to Mir, he acquiesced because of the fortune teller’s advice.

Reb Yerucham took a special liking to Saba and was mekarev him tremendously. Ultimately, he became the quintessential talmid of Reb Yerucham and expositor of his Torah.

In 1938, as a German citizen, Saba was expelled from Poland. He was forced to leave Mir, and found refuge in Sweden, which remained neutral during World War II. He worked tirelessly to help as many Jews as possible escape from the inferno engulfing European Jewry. Letters streamed to him from all corners of Europe, from gedolim such as Rav Elchanan Wasserman, Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz, and Rav Chatzkel Levenstein, with lists of names and birthdates of people requesting visas. He worked furiously day and night, Shabbos included, to secure them. In a testimony that he granted to Yad Vashem in 1966, it’s estimated that he secured around a thousand lifesaving visas.

Saba also served as a vital liaison between Rav Aharon Kotler, Rav Avrohom Kalmanovich, and the Vaad Hatzalah in America, and the Mir Yeshiva in Japanese-occupied Shanghai. As postal service between the United States and Japan was severed during the war, the Vaad Hatzalah in America couldn’t send money to the yeshivah directly. Instead, they would send it to Saba in neutral Sweden, who would repackage it and send it onward. In fact, when the yeshivah published a kuntres of chiddushei Torah in Shanghai, they included one Saba had written in Sweden and enclosed together with a shipment of vital aid.

While in Sweden, Saba also mastered the local language and wrote a Swedish-language book about the imperative to maintain fidelity to Yiddishkeit, intended to bolster Jews from succumbing to the overpowering atmosphere of assimilation in Sweden at the time. (This was actually his second book; at age 16, he wrote a German-language Torah perspective on the three dimensions of relationships: bein adam l’chaveiro, bein adam l’Makom, and bein adam l’atzmo.)

When the war was over, Saba read a news report that trains full of refugees had arrived in a certain town in Sweden. Although the report didn’t identify the refugees as Jewish, Saba thought they might be. He traveled to the refugee camp, where he found hundreds of Jewish girls, all survivors of the camps. (The Swedish government accepted 20,000 Jewish female refugees under humanitarian pretenses, but only females, because there was a surplus of males in the Swedish population and they needed to rebalance their reverse-shidduch crisis.)

The refugees were all survivors of the camps. They were deeply traumatized, and searching frantically for lost friends or cousins or relatives. While speaking with these girls in Yiddish, Saba heard a bell, and they told him that it was lunchtime. Saba had brought a sandwich and he looked for a place to wash his hands. When the girls asked what he was looking for, he told them he needed a cup to wash his hands. After washing and saying netilas yadayim and Hamotzi, he turned around to see many girls bursting into tears. They said that they hadn’t seen a Jew wash and bless over food in years. The image of a bearded rabbi saying a brachah transported them back to their homes and their now-deceased fathers and brothers and uncles.

On the train ride back to Stockholm, Saba concluded that the only way to save these girls from guaranteed assimilation was to open up a Bais Yaakov for them. Remembering a teaching from Reb Yerucham that you must act instantly when you have a good idea, he got off the train at the next stop and telegraphed the other members of the Vaad Hatzalah that there would be a meeting that evening to discuss the proposed school.

Next, Saba wrote a letter to the Ministry of Interior in Sweden explaining the situation and asking for premises to house his school. To his surprise, a couple of days later he received a positive response. He traveled back to the camp and offered the refugees the opportunity to attend a Jewish school, and a few hundred girls joined. The school opened in Lidingö on the outskirts of Stockholm, and was run by the local rabbi, Rabbi Jacobson, together with his wife. Saba came in once a week and taught Chumash. Hundreds of Jewish girls were rehabilitated in Lidingö and integrated back into Jewish life. Most of them ended up building beautiful families in Eretz Yisrael and the US.

On Their Own

In 1946, Saba left Sweden and came to Eretz Yisrael, where he married Rivka, the daughter of the Slabodka Mashgiach, Rav Avraham Grodzinski, Hashem yikom damo.

Saba and Savta were both orphaned of both father and mother, and started their new life with no money or resources. As Savta was the daughter of the Slabodka Mashgiach, many gedolim took the young couple under their wing and helped them get started. Rav Isaac Sher, Rosh Yeshivah of Slabodka, was like a mechutan at their wedding. Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer flouted the British curfew that was imposed after the King David Hotel bombing to join the Shabbos sheva brachos. Feeling uncomfortably indebted to so many people who had helped them get started, the couple resolved to make it on their own from there on.

With the direction and encouragement of the Chazon Ish, Saba founded Yeshivas Be’er Yaakov and served as mashgiach for 35 years. Together with the Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Moshe Shmuel Shapiro, he molded hundreds of bochurim into talmidei chachamim and baalei mussar. In the early years, Saba and Savta suffered from grinding poverty. When their uncle, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky (he married Savta’s maternal aunt) visited them, he cried, seeing the deprivation with which they lived. But they kept their pledge and never asked anyone for anything.

With his penetrating shmuessen and magisterial, genre-defining seforim (in particular the two volumes of Alei Shur), Saba transmitted the rich Toras Hamussar that dominated the great prewar yeshivos to ensuing generations. He was also at the vanguard of the teshuvah movement that sprang up in the aftermath of the Six Day War, traveling from one army base to another, teaching and speaking and fanning flickering sparks of emunah back to life.

Nor did he slow down as he aged. In 1982, he moved to Yerushalayim and founded the Bais Hamussar and its adjunct kollel, and began giving shmuessen in the Mir and Yeshivas Kol Torah, while also serving as Mashgiach in Lakewood East where his son-in-law, Rav Yaakov Elazar Schwartzman, was rosh yeshivah. And in his eighties, he founded Yeshivas Givat Shaul. The last sefer he published in his lifetime was Mitzvos Hashekulos, which went to print when he was already in his high eighties.

Living Mussar

Saba’s résumé is undoubtedly impressive, but the underlying thread running through it all was that he worked very hard on himself. In any analysis of Saba’s greatness, one thing is undeniable: Saba worked on himself very hard. While he always concealed his internal avodah, astute observers caught glimpses. Like all the baalei mussar, he never preached or taught something that he himself was not doing. Accordingly, all of the immense avodah described in both volumes of Alei Shur doubles as descriptions of Saba’s personal avodah.

Saba wouldn’t speak about anything unless he was currently involved and engaged in those lessons. For many years, he would give the same shmuess each week in three different places — the Bais Hamussar, Mir Yeshiva, and Yeshivas Kol Torah. He said that it got progressively harder to speak the more times he spoke about a certain subject. He never wanted to orate; everything he said was a genuine reflection of him and his own avodah. When he’d speak about a subject the second or third time, he had to invest extra work to make sure that he wasn’t simply repeating material, but still living it.

After a shmuess, he would be bombarded with questions. In the Mir, for instance, after speaking he would daven Maariv, and then be peppered with more questions, which continued for his trip home. When he would finally arrive home, exhausted, invariably the bell would ring with someone else who wanted to speak with him. My brother, Rav Eliezer Wolbe, (Rosh Yeshivas Ohr Shlomo in Yerushalayim), remembers Saba answering the door and speaking to the bochur who was there for ten to fifteen minutes. He asked Saba how he mustered patience for everyone, and Saba responded, “You need to work on patience your entire life.”

Saba worked on all his middos in order to achieve shleimus. In Alei Shur, Saba guides the reader on how to discover a complete catalog of all their middos. The objective is not merely to gain a general understanding of some of a person’s middos, but rather a comprehensive and thorough understanding of the collection of innate middos, both good and bad, that operate within a person.

Over time, the goal is for a person to assemble a picture of all his primary middos, organized in order of how prominently they feature in his life. Saba offers a diamond-shaped sample of a finished layout of a person’s middos. It’s well-known that the sample that he offers is actually his own. The best middah featured in the sample is emunah and the worst is atzlus, laziness.

My brother Eliezer observed that Saba never, ever let anyone do anything for him. He would always refuse any help. When Saba wanted to show him a citation in one of his seforim, he never allowed him to go get it for him. In line with his meticulous nature, he knew where every sefer in his library was located, but he never allowed others to do any work for him. Saba never explicitly said that he was working on his atzlus, but his actions allowed us to catch a glimpse of his avodah.

The Secret of His Greatness

When Saba passed away, I was only 18, and my appreciation for him then was primarily for his greatness as a grandfather. Since then, studying his seforim and learning more about his life and his magnificent, improbable accomplishments, has given me more of a perspective of his greatness as a gadol. My cousin’s observation that Saba will obligate everyone to achieve gadlus has become more salient in my eyes.

Rav Chaim Uri Freund, a member of the Badatz Eidah Hachareidis, once told me that he attributed my grandfather’s gadlus to his tremendous shemiras einayim. A hallmark of all the baalei mussar was their effort to achieve complete self-control. Their every movement was the product of a decision that they made, never the result of petty whims or mindless impulse. Saba told us that the Alter of Kelm would never move his eyes. They were always facing straight ahead as if permanently hammered in place. If he wanted to look to his side, he would swivel his entire head.

In a similar vein, Saba wrote about a kabbalah Reb Yerucham made, (found in his journal) to do five things every day against his impulses, and a self-imposed penalty in the event he did not. This is a superb method to gain self-control, infuse every act with purposefulness and mindfulness, and to cease being like a mindless marionette manipulated by the yetzer hara.

Saba strived to attain this level of self-mastery as well. For many years, on Shabbos afternoons he would walk from his house in Givat Shaul to Bayit Vegan, where he would speak in Yeshivas Kol Torah as Shabbos ended. My brother Eliezer once walked behind him at a distance and saw how Saba looked downward the entire way, without turning around once. He didn’t want to see chillul Shabbos, and even though he was machmir to remove his hearing aids on Shabbos, he somehow sensed when it was appropriate to cross the street without looking up. He was always immersed in thought, and he kept his eyes down.

Others have suggested that his impeccable integrity in monetary matters was the secret. After the war, Saba sent a detailed letter to Rav Avrohom Kalmanovich accounting for every dollar that had passed through his hands, until the last penny. Despite subsisting on a starvation diet himself, he did not touch a nickel from that money, and chronicled all the inflows and outflows with characteristic fastidiousness and precision. Reb Avrohom was so impressed by this letter, he showed it to the Brisker Rav.

Saba’s self-mastery also extended to not demanding what was rightfully his. His father was a collector of memorabilia and actually owned Rabi Akiva Eiger’s two-volume set of Mishnayos with his handwritten notes on the margins. This priceless set was bequeathed to Saba, and he kept it in his house, until someone stole it. While Saba knew who stole it, he refused to divulge the thief’s identity or take any measures to recoup it. Likewise, during the war, he sent a shipment of other priceless memorabilia to a “friend” for safe- keeping. The friend never acknowledged it or returned the items, and Saba never confronted him.

My grandmother said that Sweden was the crucible wherein Saba’s greatness was formed. He was alone in a place where the winds of assimilation were very strong. In his writing, he describes how he learned mussar every single day, which helped him overcome the monumental nisyonos. Our uncle Rav Ezriel Erlanger, the mashgiach of the Mirrer Yeshivah in Brooklyn, said that Saba told him that every single time he left his room in Sweden and kissed the mezuzah on his way out, he wondered to himself if this was the last time that he would walk out as a ben Torah. But ultimately, not only did Saba preserve his standing as a ben Torah in Sweden, he became an adam gadol.

Saba himself always refused to take credit for his successes, attributing them to a variety of people other than himself. In his introduction to the first volume of Alei Shur, he attributes his success to his righteous rebbetzin, and to his pious and noble mother, Rosa Rivka. He would recount how she would drop him off at the local Orthodox Rabbi in Berlin to learn Mishnayos, and when he would look back, he would see tears streaming from her eyes as she davened for him. In the introduction to volume two, Saba credits his success to the zechus of his father-in-law, Rav Avrohom Grodzinski.

Toward the end of his life, my brother Yoni and I learned in Yeshivas Yad Ahron, where Rav Yisrael Meir Homnick, a close talmid of Saba’s, served as mashgiach. He told me that when he once visited Saba, Saba inquired about us, and Rav Homnick told him we were doing fantastically, (true for Yoni, more charitable for me). Upon hearing that, Saba told him it was in the zechus of the Chazon Ish, who came to Be’er Yaakov two weeks before his petirah to serve as my father’s sandek. Rav Homnick pushed back, saying that perhaps some of the credit was due to Saba, but he refused to hear it.

Around Saba’s Table

Though I lived in America while Saba lived in Eretz Yisrael, while growing up, I still got to spend a fair bit of time with him. My grandparents would come occasionally for Yom Tov, and our family moved to Yerushalayim to be closer to him for a two-year stint when I was seven, and a four-year stint when I was 16. Some people assume that a grandfather who was also a gadol and baal mussar must surely have been domineering, exacting, and always showering everyone with withering criticism. Any infraction of mine in school elicited a reproving reaction: “I don’t think your grandfather would approve of that!”

When I met my maggid shiur on a bus while not wearing a hat or jacket, he said, “Read what your grandfather wrote about always dressing as a ben Torah.” When I once davened at a later minyan, someone who glanced at the name on my tefillin bag told me he couldn’t believe that Mashgiach’s grandson didn’t always daven neitz, (after a teary-eyed tikkun chatzos, naturally).

But to us, Saba was a grandfather, not a gadol. He wasn’t judgmental. He would never impose. He wasn’t demanding. He was normal, even playful. He gave out Kiddush with a sing-song jingle. When he dispensed challah, he playfully jammed the challah directly into the mouth of any grandchildren sitting close enough to him. When I was six, I challenged him to a game of chess (he won). When I was seven, I stole his afikomen (my father encouraged me to snatch it fast because he had lightning-quick reflexes). He would wake us up for Shacharis (if we asked) by playfully dropping his tzitzis into our ears. When my brother Eliezer asked him to wake him up at 6:45 for a 7:15 Shacharis, he said, “That is basically in the middle of the night!” Every Motzaei Shabbos, we grandchildren would visit and sit around the tiny table in the tiny room that served as living room, dining room, and study, and chat. He was always immersed in thought, always subsumed in avodah, and we could chat around the table without him noticing.

He was always deep in thought. The memorable pose that we all associate with him is his head leaning on his hand in concentration. He was always alive, dynamic in his spiritual life.

He frequently highlighted the importance of always having a sugya to work on, and he always practiced what he preached. He was once sitting on the dais at a bar mitzvah when the person next to him confided that he was afraid he would be asked to speak and he had nothing prepared. Saba was baffled: “Just say out loud what you are currently thinking about!” he said.

Even when we sat around his table, he was in his own private world — a rich and robust internal world. His deafness, which he suffered from since childhood, helped deepen his oblivion to the world outside. To speak with him, you needed to talk loudly and directly into his hearing aids, so unless we specifically directed his attention to us, he was with us — but in his own world.

One Motzaei Shabbos, Yoni, a favorite of his, walked in. Someone got Saba’s attention and told him, “Yoni is here!” Saba looked directly at Yoni and feigning seriousness said, “I don’t see Yoni; I just see a hat.” When Yoni removed his hat, Saba’s eyes lit up. With a huge smile he exclaimed, “Ooooh! Yoni!”

Serving Until the End

In the last weeks of his life, I got a glimpse of my own of Saba’s avodah. During those final months, he was in intense agony, and would wake up every night in pain. Every night a different grandchild would stay with him to assist and attend to him until Shacharis at 7 a.m. One of those nights, when I had the privilege of staying with him, I saw a side of him I hadn’t seen before.

Halfway through my shift, Saba woke up and asked me if it was time for Shacharis. I responded that it was only 3 a.m. and he went back to sleep. Half an hour later, again, he awoke and asked if it was time to daven; again, I encouraged him to go back to sleep. At four he awoke again, and — with the eagerness of a child the night before a trip to an amusement park — insisted on getting dressed and preparing for Shacharis. I helped him get ready (a painful and laborious process given his condition), and he sat on the bench in the foyer, his hands resting on his knees, fully dressed in his frock and hat, patiently waiting until it was time to daven.

Reb Yerucham taught that we daven three times a day because davening is as necessary for our neshamos as food is for our bodies. The three tefillos are three daily spiritual “meals,” he taught. Indeed, Saba always davened Minchah gedolah, even when the yeshivah only davened later. How can you go 14 hours without davening? While for many of us, davening is a chore, and ideally, we would like to bunch Minchah and Maariv together, Saba davened with “hunger.” His relationship with Hashem was real; his emunah was palpable.

Though Saba didn’t say a lot of divrei Torah on Leil HaSeder each year, there was one idea he consistently repeated. He would tell us that the tremendous gilui Shechinah that happened at Yetzias Mitzrayim is revisited each year on this night. “V’achshav kervanu HaMakom l’avodaso” — right now, he would stress, when we are at the Seder, we are close to Hashem in a way resembling that miraculous night 3,300+ years ago.

Saba always cautioned that real growth happens slowly and incrementally, with small actions and small kabbalos effectuating tremendous change over time. Skipping rungs on the ladder of growth will ultimately prove to be counterproductive, with one exception. Seder night, he said, allows for radical, revolutionary change all at once.

That final Seder in the hospital with Saba was indeed a transformative experience for me. Watching a true eved Hashem dealing with his final illness with grace and composure was a tangible example of “V’ahavta es Hashem bechol nafshecha — afilu notel es nafshecha.” Saba used to say how apropos it was that Rav Yisrael Salanter, who emphasized bein adam l’chaveiro, especially with regard to Choshen Mishpat, was niftar during parshas Mishpatim. In a similar vein, it seems only fitting that Saba, who dedicated his life to achieving and living emunah, was niftar during the Yom Tov of emunah.

No matter our starting points, we can achieve gadlus. Saba obligates us all.

Rabbi Yaakov Wolbe of Houston, Texas, is an author and a prolific Torah podcaster. He serves as Director of Global Outreach for TORCH.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1057)

Oops! We could not locate your form.