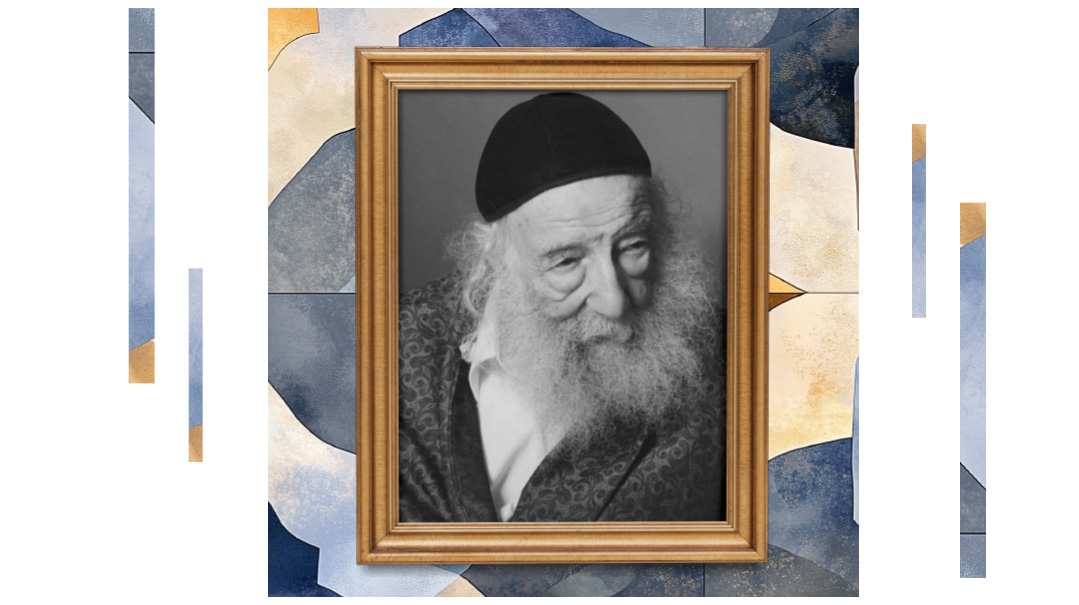

So Strong Yet So Simple

Rav Nota Schiller ztz"l, founder of Ohr Somayach, spent the last 50 years in the forefront of the kiruv movement

Photos: Ohr Somayach Archives

Rav Nota Schiller, founder of Ohr Somayach, spent the last 50 years in the forefront of the kiruv movement, but while times have changed, his basic method never did: Expose students to the truth of Torah, let them wade through a page of Gemara, and everything else will follow

Over half a century, tens of thousands have walked through the iron gate on Rechov Shimon Hatzaddik, up the few steps of Jerusalem stone, and into the pulsing beis medrash of Ohr Somayach Jerusalem. They came with questions, reservations, doubt, and at times, resentment. And after a year or two they left, many going on to become true talmidei chachamim with a profound understanding of life’s true meaning.

What happened in the interim?

The answer, Rav Nota Schiller would say, lies in one word: truth. They saw truth.

Rav Nota, who passed away last Shabbos at age 88, served as Ohr Somayach’s rosh yeshivah since its inception in 1972, at a time when the term “kiruv” was barely used.

But to him, the cries of thousands of Jewish souls being robbed of their heritage was too powerful to ignore. He, together with Rav Mendel Weinbach and Rav Noach Weinberg, and Rav Yaakov Rosenberg, founded a yeshivah for baalei teshuvah called “Shema Yisrael,” which turned into Ohr Somayach after Rav Weinberg went on to found Aish HaTorah in 1974 (Rav Rosenberg later opened Machon Shlomo in 1982).

Rav Nota, an extraordinarily talented orator, threw himself into the project with superhuman devotion, traveling all across the world to fundraise and recruit on its behalf, creating a destination for thousands of young people plagued by questions, desperate for answers.

And Rav Nota gave them answers. Or as he might say, one answer. “The truth.”

That meant Gemara. In depth.

“The truth… it sounds like a cliché right?” he said in an interview with Mishpacha back in 2015. “Like the coach who instructs the hitter to ‘hit a home run.’ It’s easier said than done. We have a yeshivah. We learn Gemara. B’iyun. That’s truth, and if you start with that, you work backward.”

As he once said in a shmuess to his talmidim, “Ideally, one should stay here long enough so that on the day you leave, if you end up on a ship that gets hit by lightning and you’re marooned on a desert island with only a Gemara, you wouldn’t be bored.”

In the Gemara lies all the kedushah for which the neshamah thirsts. Give it to them, insisted Rav Nota. Let them drink its waters.

They will come to love it.

Rav Nota would go on to hire a staff comprised of the most brilliant and talented talmidei chachamim of the day, each tasked with the same mission statement. Teach them Torah. Let the force and fortune of Torah itself inspire their path forward.

And perhaps Rav Nota was so keen on this approach because he was so attuned to the soulful cry. He would say that the term “kiruv,” which means “bringing close,” can connote our duty to listen to our brethren’s soul cry. “We must come close enough to hear the neshamah inside, screaming.”

From Their Own Ranks

By Yonoson Rosenblum

R

av Nota Schiller was one of the triumvirate of founders of Shema Yisrael in late 1972 — the other two were Rav Noach Weinberg and Rav Mendel Weinbach, with Rav Yaakov Rosenberg joining them a short while later.

Shema Yisrael gave rise to both Ohr Somayach and Aish HaTorah, and eventually Machon Shlomo as well, but actually, Rav Nota’s partnership with Rav Noach went back more than a decade earlier, when the two close friends from Ner Yisroel were learning together in the ITRI Kollel. It was 1961, the summer of the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, and the two met three national leaders of the Young Judea movement, whom they enticed to start learning with them. In time, they convinced the Blumenfeld twins, Mordechai and Yisrael, to forgo their scholarships at Columbia and Harvard, respectively, and convinced a third friend to leave Barnard for Gateshead Seminary.

That initial success whetted Rav Nota and Rav Noach’s thirst for more, and hinted to the possibility of attracting secular Jewish youth.

In 1965, they opened up Midreshet L’Tzion in Jerusalem’s Talpiot neighborhood, and subsequently added a kollel of outstanding young talmidei chachamim. But when the Six Day War broke out, the funding from non-Orthodox Jews completely dried up and went to supporting the war effort. The young Schiller and Weinberg families did everything possible to keep the yeshivah going, including pawning their wedding silver, but it was not to be.

BY

the time I took my first tentative steps into Ohr Somayach in the summer of 1979, Rav Nota and Rav Nachman Bulman were the first stops for any potential new student for whom the registrar felt there might be only one chance to make the “sale” to stay and learn for a period of time.

Rav Nota was highly articulate — his rich English vocabulary was a perennial subject of the Ohr Somayach Purim shpiel, he possessed broad secular as well as Torah knowledge, and could speak about anything the potential recruit wanted to discuss.

A photo of Cal Abrams, a Brooklyn Dodgers outfielder of the 1950s, rested on the bookshelf next to his desk, and Rav Nota was always happy to discuss Abrams’s flash of remarkable success before teams adjusted the placement of infielders to counter his left-handed pull hitting.

As a friend from that period put it to me after Rav Nota’s levayah last Motzaei Shabbos, for those who imagined themselves more intellectually sophisticated than they were, Rav Nota was able to quickly establish that one could be mitzvah observant without sacrificing any of one’s rationality or intellect. Ohr Somayach would make the case for Torah, he made clear, without asking you to accept anything on blind faith. And as burdened as he was, Reb Nota would make the time to learn privately the Rambam’s Sefer Hamada with those who needed a little more convincing.

No matter how intellectually sophisticated one’s background, one could be confident that one’s parents would be deeply impressed by Reb Nota. And that was important. More than one friend of almost sixty years commented to me at the levayah, “I would not be frum today if it were not for Rav Nota.”

AS

much as he loved Torah learning, and could readily draw on a vast storehouse of Torah knowledge in his derashos, Rav Nota sacrificed a portion of his own personal Torah learning to hold Ohr Somayach afloat, just as had the Ponevezher Rav in his time. Virtually the entire fundraising burden fell upon him. And there were times when he made three trips to the States in a month.

It would be impossible to give even the sketchiest portrait of Rav Nota without mentioning his seamless partnership of four decades with Rav Mendel Weinbach, until the latter’s passing a little more than a decade ago. I had a number of occasions to sit together with the two of them in Rav Nota’s much larger and well-appointed office (for the purpose of entertaining dignitaries and donors), and not once did I detect the slightest trace of friction between them.

Both knew and accepted their respective roles, and with gratitude and respect to the other — Rav Nota as the face of Ohr Somayach to the outside world; Rav Mendel as the rebbi to the rebbeim of the yeshivah.

Above all, the two men were united by a common approach to talmidim. Ohr Somayach was always characterized by a Gemara-centered curriculum, with the goal that talmidim would integrate in time into the mainstream yeshivah world. In my day, Rav Aharon Feldman, today rosh yeshivah of Ner Yisroel, gave the highest shiur, and the beis medrash was filled with major talmidei chachamim, including Rav Mordechai Isbee a”h, and Rav Moshe Carlebach and Rav Yaakov Shatz. And for the most advanced kolleleit, both Americans and Israeli, there was a kollel headed by two of the greatest contemporary talmidei chachamim, Rav Berel Schwartzman and subsequently Rav Moshe Shapira a”h. Rav Nachman Bulman, the mashgiach, opened up the full panoply of Torah thought.

The success of graduates of Ohr Somayach in the larger world of Torah learning was a point of particular pride for Rav Nota. Rav Avraham Koenig Connack, who gives the highest Gemara shiur, and Rav Shlomo Weiner, the recently appointed rosh yeshivah, both come from the ranks of former Ohr Somayach talmidim. And Rav Nota had an entire bookshelf in his office dedicated only to the seforim written by former Ohr Somayach talmidim.

Nothing gave him more satisfaction than the Torah scholars produced by Ohr Somayach, with the possible exception of the gadlus in Torah of his own sons and sons-in-law. His oldest son, Rav Nachshon Schiller, is the founder and rosh yeshivah of Jerusalem’s Ohr Shmuel yeshivah ketanah, and many of his sons-in-law are prominent maggidei shiur.

And above all, there are the thousands who have passed through the yeshivah he built and whose lives were changed forever as a consequence.

Ahead of the Game

By Hanoch Teller

R

av Nota Schiller would point to the “Rescue Area” sign affixed by the municipal fire department in front of Ohr Somayach and comment, “They got that right.”

Rav Schiller saw to it that the yeshivah for baalei teshuvah would best be able to save young men drowning in a society bereft of Torah. Under Rav Nota’s guidance and dynamic leadership, the yeshivah opened its doors to all, offering a talented and varied staff that was anything but cookie-cutter. He knew that students coming from wide-open and varied academic worlds would not fare well in a one or two-dimensional learning environment.

What the Ohr Somayach rookies were exposed to was an eclectic group of scholarly teachers who would carve out an individualistic educational program that would properly fit the incomers. The idea was reflected in the name of the yeshivah that would be a “Happy Light” to those who entered, and at the same time a memorial to the brilliant scholar — the Ohr Somayach, Rav Meir Simcha of Dvinsk — whose moniker the yeshivah adopted. And just as the Ohr Somayach (the scholar) was a buttress against the so-called Enlightenment movement, Ohr Somayach (the yeshivah) would continue to shelter and nourish Jewish students who had been raised on concepts antithetical to Torah ideology.

The methodology of Ohr Somayach, hammered out by Rav Nota and his co-rosh yeshivah, Rav Mendel Weinbach a”h, was unique in light of other yeshivos that cater to baalei teshuvah. The thrust of Ohr Somayach education, very much crystallized by the late mashgiach, Rabbi Nachman Bulman a”h, is classic yeshivah study focusing on Gemara — the idea that nothing can better entice a young man to Judaism than its most critical component: Torah study.

This came with a side benefit and critical perk. Focusing on Gemara best prepared those who matriculated from Ohr Somayach into conventional yeshivos later on. This was indeed a directive from Rav Nota’s rebbi, Rav Yitzchok Hutner, who said, “If your students remain a cult unto themselves, you have failed. If they can successfully matriculate into the Torah world upon graduating Ohr Somayach, you have succeeded.”

Rav Nota would often say that whereas all Jews are enjoined to observe 613 commandments, a baal teshuvah has an extra positive and an extra negative commandment: “Thou shalt be normal; and thou shall not be weird.”

Intense Talmud study was the greatest diet to ensure this outcome, or as Rav Nota labeled it, “Project Perspire.” Sweat over a Gemara and you are guaranteed to grow (in the right direction).

Indeed, when I was a rebbi for beginners in Ohr Somayach in 1982, teaching recruits that Rav Meir Shuster a”h had just “scraped off the rocks,” I taught — on directive from Rav Mendel and Rav Nota — various selections of Talmudic discussions, sans philosophy, etymological high-wire acts, histrionics, or gesticulations.

F

or decades, Ohr Somayach alumni can be found integrated in many premier yeshivos without recognizable luggage of their origins. A common theme of the Ohr Somayach Purim shpiels of the 1990s was of a dreamy-eyed Ohr Somayach student wearing a black hat with the brim up, as “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” played in the background, while the Omniscient voice sonorously swooned, “I do not have to always be here; one day I’ll make it to the Mir….”

Rabbi Zevi Kaufman, director of communications at Ohr Somayach, told me that not only was Rav Nota insistent that Gemara could light up a dormant soul, but it was the duty of Klal Yisrael to ensure this interaction.

“Every Jew has an inborn right to a Jewish education, and this was Rav Schiller’s rallying cry that the rebbeim and talmidim at Ohr Somayach feel flowing through their veins,” he said.

As everyone knows, for a yeshivah to operate it needs funding. In the case of Ohr Somayach, where the yeshivah aimed to encourage not-yet-religious students to enter, tuition was hardly ever a consideration. Accordingly, Rav Nota Schiller carried the brunt of the yeshivah’s fundraising upon his broad shoulders.

An exceptionally articulate gentleman (in English, Yiddish, and Hebrew) he could convey his message with Churchillian intonations and nudges of moral suasion. In private conversation, he could go on and off the record with such speed and dexterity that you felt as if you were engaged in verbal aerobics. He resolutely refused to dumb down his speech, his vocabulary rich, florid, and poetic.

Rav Schiller’s eloquence always scored major points with political and military leaders who visited the yeshivah, and he had no trouble engaging intellectually with academics and scholars from secular backgrounds. He was also able to marshal humor and trenchant and realistic examples when explaining complex theological concepts.

To be sure that he was properly grounded, Rav Nota would consult with gedolei Yisrael frequently, most notably Rav Shach, to be certain that the yeshivah was pursuing precisely the correct path.

To concretize (one of his favorite words) is how Rav Schiller lived his life. Many people have lofty ideas, but he carried them out — never allowing a budgetary crisis or any other kind of crisis to get in the way. He loved his People and he loved the Almighty and he devoted his life to bridging them together.

“B

ridge” was an operative word regarding another significant aspect of Rabbi Schiller.

It was Rav Nota who persuaded the great bridge builder, Joseph Tanenbaum of Toronto, to contribute and fight for Jewish education.

Their introduction represented an oddity that was uniquely theirs. Tanenbaum, who passed away in 1992, was building bridges and developing property and was so impressed with Rav Schiller that he offered him a job.

Rav Schiller declined the offer but came up with a counterproposal of his own: “Joe, I’d like to take you into my business.”

Rav Nota laid out his utopian plan to create a yeshivah for a nascent baalei teshuvah movement, which met with incredulity wherever he proposed it. The very impossibility of the plan is what intrigued Tanenbaum.

How did he fulfill his dream so magnificently? This backstory is enlightening.

Rav Schiller wished to speak with Joseph Tanenbaum about a major donation for a good cause. It was the dead of the winter, but instead of hibernating, JT (as he liked to be called) was up to his ears at work. Since he was spending the better part of that week at an industrial machine exhibition, he was unable to accept any appointments at his office.

At five o’clock each morning, Joe could be found, together with those who unlocked the gates at the exhibition grounds of the machine show, on the shores of Lake Ontario. The equipment was too big to fit inside a conventional structure.

JT never denied anyone the opportunity to see him, but under the circumstances, the warm comfort of his office was simply not an option. Rav Schiller, for his part, had one thing on his mind — the same thing that he always had on his mind — the future of the Jewish People. The venue wasn’t important.

He pressed, and Joe agreed to his request for an appointment. “Be down at the exhibition grounds at six o’clock tomorrow morning. There won’t be anybody else there yet, so you’ll have no problem finding me.”

Rav Schiller arrived on time for the meeting and indeed found that he had Joe all to himself. But he had trouble communicating in the cold — his body shivered, his teeth chattered, his nose began to run, and the icy winds made his eyes tear. Rav Schiller, who enjoyed a richly deserved reputation for eloquence, had planned this presentation for hours. Yet in that outdoor icebox, the scholar began to stammer uncontrollably as if the words had frozen inside his mouth. From all the stuttering and stammering, JT did not understand Nota Schiller clearly, and thought that he had been asking for a sum three times his actual request. Rav Nota’s supreme efforts were rewarded and JT ultimately promised what he thought he had heard.

Rav Nota did not merely bring Joseph Tanenbaum into a career of philanthropy, but in the process became his closest friend, the two of them enjoying a special chemistry. JT helped Ohr Somayach in a very profound way, yet from his perspective, he got the better of the deal, as it enabled him to invest his fortune into such a worthy cause. Rav Nota, for his part, helped JT locate other laudable educational institutions in which to “invest.”

Because of the friendship between the two, Ohr Somayach received over half of its operating budget from the Joseph and Faye Tanenbaum Foundation. Ultimately, when the new building was erected, it bore the banner of “Ohr Somayach Tanenbaum Educational Center.”

JT wistfully fancied that one day maybe one of his grandchildren would visit Jerusalem and see his grandfather’s name on the building and would be intrigued and peek inside. And then who knows?

As is most deserving for a man of such generosity, JT’s grandson, Yaakov Kaplan, not only entered the building, but became a proud student of the yeshivah, and today one of the yeshivah’s most stalwart supporters. From day one, Rav Schiller was Yaakov’s rebbi, and even after Yaakov Kaplan returned back to Toronto to work in his grandfather’s business, the two conversed on a weekly basis.

Rav Nota’s tenacity was not the only factor that yielded funding. His insight into people and keen sense of timing reaped benefits for which no one else would have the stomach. When I arrived in Israel in the mid-1970s I was told that on a fundraising mission in St. Louis, a philanthropist offered Rav Nota a sum of $40,000. Rav Schiller refused it, reasoning that this gentleman could stretch further. Two years later Rav Nota walked away with a check for a quarter of a million dollars. That kind of patience, confidence, and timing, was uniquely his.

In Rav Nota’s frequent excursions to raise money for Ohr Somayach, whether or not he secured funding, he never failed to impress wealthy philanthropists and business leaders about the value of traditional Jewish education, even to those from radically different backgrounds.

Rav Schiller was an ardent baseball fan and even has a spectacular picture of Koufax in his windup adorning the wall outside his office. But like everything Rav Nota was knowledgeable about and privy to, it all came back to supporting and enhancing Torah learning.

For example, any authentic baseball aficionado knows about the over-the-shoulder Willie Mays catch in the eighth inning of the tied first game of the 1954 World Series. Referred to simply as “The Catch,” Mays upgraded the backward catch by turning on a dime and firing the ball into the infield to prevent a run from scoring. How was he able to pull this off?

As Rav Nota would tell it, “Mays responded, ‘I’m a talmid of Leo “The Lip” Durocher. He taught us that the ball don’t do no good in the outfield, only in the infield can it be of use.’ ”

And with all the charm in the world, Rav Nota would tell his audience of potential donors, “You gentlemen are the infield. Without your assistance, the ball remains in the outfield, and that is not going to get any boys into yeshivah.”

Each time, Rav Nota would hit a home run.

A Mission to Align With

I first heard Rav Nota Schiller speak when, as a bochur, I had joined my father on one of the famous Mentors Missions, where balabatim come to learn Torah with beginner-level college students. He spoke with such conviction and tenacity. A rigorous belief in the truth, power, and ultimate relevance of Torah. His mastery of language. His power of metaphor. His message was unapologetic and infectious. I knew then, one day, this would be a mission to align with.

I had learned in classical yeshivos and kollelim prior to having been offered the position of helping launch the J101 program at Ohr Somayach, a ten-month learning and internship program for beginners to Jewish learning. For the better part of a decade, it has and continues to be a most exhilarating and fulfilling position, to take part in the execution of Rav Nota’s mission of bringing Yidden back to Hashem through in-depth study of the Torah itself.

Aside from our impactful in-person interactions as faculty in Ohr Somayach, I also had the honor, during the Covid pandemic, of doing tens of hours of interviews with Rav Nota (subsequently released on the Ohr Somayach Podcast) in which we unpacked the history of the teshuvah movement, the personalities involved and lessons learned in the development of the greatest innovative movement within Judaism (perhaps since Sarah Schenirer’s Bais Yaakov movement).

I once asked the Rosh Yeshivah how he would define the unique sales proposition of Ohr Somayach. After all, there are so many yeshivos out there, each with their own derech and flavor catering to the varied demographics of the Jewish world.

Rav Nota’s unequivocal answer was, “We are the learning people, we are the people of the book.”

He held the unwavering belief that beginners could truly become independent learners of Jewish texts in their original Hebrew-Aramaic format and over time with the required effort, blossom into authentic talmidei chachamim. Rav Nota lived with a tenacious belief in the ability of the light ensconced in Torah itself as the most formidable tool to bring our brothers without a Torah or yeshivah background to the truth and sweetness of authentic Judaism.

Rav Nota celebrated the goalposts along the way, but led with the ultimate vision of empowering late beginners in becoming future authentic bnei Torah with the ability to develop their own cheilek in Torah.

Ohr Somayach is often described as a field hospital for neshamos — how fast can we nurture this parched neshamah back to health through a daf of Gemara? That was Rav Schiller’s rallying cry: That every Jew has an inborn right to a Jewish education. And although it’s a darker world without the Rosh Yeshivah, his message continues to inspire the rebbeim and teachers he left behind, and his legacy continues to illuminate the world through the thousands he continues to impact until today and onward.

Yehi zichro baruch.

—Rabbi Zev Kaufman

Rebbi at J101 Program and director of communications, Yeshivas Ohr Somayach Yerushalayim

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1053)

Oops! We could not locate your form.