Never Bend

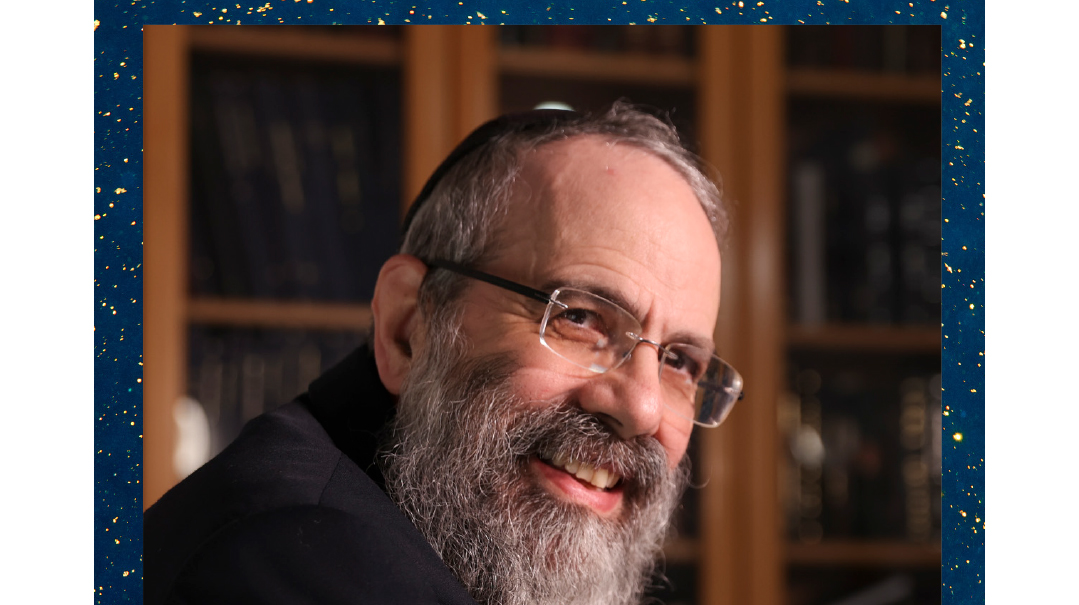

| May 13, 2025Zalman Yudkin was an unwavering Jew who soldiered on for Yiddishkeit under the Soviet regime, then moved on to be a beloved international fundraiser until he passed away last year at age 98

Photos Family archives

He was an unwavering Jew who soldiered on for Yiddishkeit under the Soviet regime, then moved on to be a beloved international fundraiser until he passed away last year at age 98. Zalman Yudkin was a familiar figure in shuls and homes in Jewish communities worldwide, a hard worker with a grueling daily schedule who would bestow the warmest brachos whether you gave a dollar or a thousand

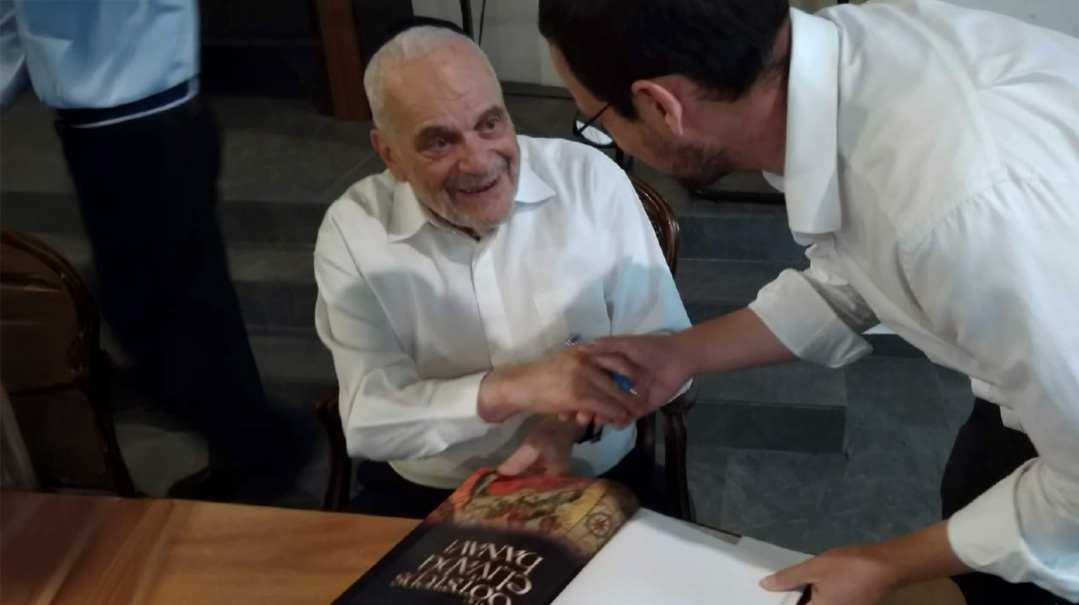

Rav Zalman Yudkin lived a long life. Just days before he passed away last year, a visitor from Lakewood asked him how he was. “Baruch Hashem, for being 99 years old, I’m doing well,” he replied with his characteristic humor. “Although I am really much younger, because the years when I lived under Stalin hoben nisht geven gelebt — were not really lived!”

Rav Yudkin of Crown Heights, whose first yahrtzeit was on 2 Iyar, was a tayere Yid who endured a lot in his long and challenging life. As a young man, he lost his entire family in a pogrom, was sent to a concentration camp, then drafted into the Russian army, and afterward subjected to the brutality of the KGB in Communist Russia for his determination to keep mitzvos. After moving to Eretz Yisrael in 1969, he spent many years working as a fundraiser for Chabad, and was a familiar figure in shuls and homes in Jewish communities worldwide. He was a hard worker with a grueling daily schedule, rising at five or six in the morning, going to the mikveh before davening, and starting his rounds, only returning home at 11 p.m. In his younger years, he’d walk everywhere, covering block after block, even at the height of summer. He would tell people that the Lubavitcher Rebbe had given him a brachah that he’d have good legs.

He would learn with other Russian Jews on the phone, and when he sat down to eat, he often had headphones on, listening to shiurim, maybe learning Tanya. He recited Tehillim continuously and sometimes spoke in various yeshivos. On his shoulders, he wore a knapsack with a pair of tefillin.

“Rav Yudkin went all over Boro Park to put tefillin on people,” says Mrs. F. from Brooklyn, who baked bilkes and cakes for him for many years. “We knew that at about 8 a.m. on Fridays he would be at a certain suit store, so my girls would deliver a package to him there so that he wouldn’t have to stop by and would have more time for his mitzvos.

“He just spent all his time on avodas Hashem,” says Mrs. R. from Monsey. “I can remember him coming back to the house at 11 p.m., so tired. He’d say he was too tired to say Shema properly, so he’d first take a short nap and then get up with enough energy to say Shema.” Every evening he’d say Vidui, sobbing, together with Krias Shema. This took him a full half hour.

He left a mark wherever he went, even in the bustling space of busy shtiblach and packed shuls, leaving many people with fond and respectful memories. Rav Yudkin took the challenges of his own life — his suffering in Russia, spending so much time far from home while fundraising, and the loneliness at the end of his life — in stride, never complaining or discontented. Anyone who heard him learning with a chavrusa over the phone could tell that every page he learned made him happy. “In Russia, every day I got up and could say Modeh Ani was another day that I’d survived, and for that alone I was so thankful to the Eibeshter,” he once explained.

Go Down Standing

Rav Yudkin was born in 1925, in Riga, to Yehuda Yeedl and Shayna Risha. His parents were staunch frum Yidden, who watched with dread as the Communists began their crusade to forcibly eradicate any vestige of Yiddishkeit. Decades after it happened, Rav Yudkin remembered overhearing his father crying to his mother, “We’ve lost our children!” the night before he began to attend school. While in his early childhood he still learned in a cheder, the Communists soon shut it down, and his father was overwrought at the prospect of sending his children to a Communist school. The price of noncompliance was too high. It would have meant the government would deem the parents unfit to raise their children and remove the children from their custody.

Rav Yudkin recalled the psychological tricks the schools played on the young, impressionable children. The teacher would lead the students to a water fountain in the hallway, which wasn’t working. She would tell all the children to ask their G-d for water, and the Jewish children to make a brachah. They’d turn the knob, but nothing came out. Taunting them, she’d urge the Jewish kids to make a brachah louder, to call with all their might to G-d for water. Nothing came out. Then she would instruct everyone to ask Comrade Father Stalin for help, and suddenly, water flowed in abundance. Rav Yudkin said that he himself only realized later in life that there was obviously another teacher on the other side of the wall who opened the spigot.

This was just one example of the psychological pressure exerted on the students. “How could you expect the Jewish children to remain believers?” he would ask. Although he himself remained absolutely strong in his service of Hashem, Rav Yudkin never expressed the slightest bit of blame for those who succumbed to the Communist pressure and loosened their grip on Yiddishkeit. He believed that it is impossible for people living in freedom to understand the oppression, deprivation, and psychological manipulation the Yidden in the USSR faced.

His own refusal to let go of his beliefs, even at great personal expense, was most likely forged by his parents’ fiery faith. He would often recall his mother’s hot tears at lichtbentshen. He would sometimes retell how one Tu B’Shevat, his parents managed to obtain some fruit. His father took him to the window of the tiny apartment whose kitchen and bathroom they shared with gentile families, and showed him a tree.

“Do you see this tree?” his father asked. “It stands strong and tall. Wind, rain, and hail cannot do anything to it. Even if it will eventually break, it stays in one piece. You too, my son, never compromise, never bend. If you will have to die for Yiddishkeit, do it standing up.”

Reb Zalman remembered one Pesach, sitting around a bare table. Even the most valiant efforts could not procure matzah in Communist Riga that year. Then his father came in, placed three sugar cubes on top of each other, and pointed to each individually, saying, “This is the Kohein, this is the Levi, and this is the Yisrael.”

A Carriage and a Prayer

World War II brought an end to Reb Zalman’s childhood. The Nazis occupied Latvia in July, 1941, and the Jews of Riga were hunted down in cruel pogroms. His mother and younger sister were among those murdered, Hashem yikom damam. He himself was taken to a concentration camp, and when at last he was liberated by the Russian army, he found himself utterly alone, as his father had been killed as well.

Reb Zalman was forcibly drafted into the Russian army and while he barely spoke about the war years, he did occasionally mention having fought the Germans. Reb Zalman managed to put on his tefillin in secret every day. He would often volunteer to serve on guard duty, since this offered him some time in peace, alone, where he could daven. When he was once caught saying Tehillim, he was beaten severely, not just for being distracted, but for saying Jewish prayers.

After being discharged from the army, Reb Zalman went back to Riga, the lone survivor of his family. He found work in a factory and made a deal with the foreman that he would come to work on Shabbos but not actually do any work, in exchange for giving the foreman the day’s wages. When someone reported him, he took the punishment and refused to betray the foreman who had helped him.

Reb Zalman married Yenta nee Chazan, a Jewish girl whom he met at the factory. Originally, Yenta came from a very religious litvishe home, but the pogroms and the destruction of the community had torn her away from her family at a young age. Reb Zalman and Yenta married and settled down in Riga. Yenta was an eidel, refined young woman who looked up to her husband all her life and supported him in observing all the stringencies he took on himself.

Latvia in the 1950s wasn’t an easy place for a family looking to clandestinely keep mitzvos; the Soviet regime was extremely harsh. In every shul that was allowed to remain open, there was a KGB informer on every bench. Years later, Rav Zalman would recall how when his wife was expecting their first child, they both hoped fervently for a girl, who wouldn’t need a bris milah. Ultimately it was a boy, and they were thrust into a terrifying predicament. “Don’t even think of circumcising him!” a well-meaning doctor warned the couple.

At first they postponed the bris, but eventually, Reb Zalman gathered all his courage and approached a mohel. The mohel, himself terrified of KGB reprisals, arranged that he would come in the middle of the night, do the bris, and run, leaving the parents to bandage the child themselves. Reb Zalman agreed, not realizing that snooping neighbors had been primed to inform the KGB if they heard the baby’s sharp cries of pain. When the police burst into his home, he still had blood on his hands.

Reb Zalman found himself sitting in jail with coarse Russian criminals and lowlifes. “Men flegt mir shlugen” (they [other prisoners] used to beat me), he explained to Mr. Shauly Katz, a driver and close confidant. Since he wouldn’t share the reason he was in jail, the inmates suspected he was a KGB spy and he suffered from their abuse — in addition to the beatings from the guards, the crowded cell, tiny rations, and rodent infestation. When he was released, he was so weak that he didn’t even have the strength to walk up the steps to his apartment.

While Yidden traditionally daven for their children and often have great ambitions and lofty goals for them, Rav Yudkin once commented that in the USSR, he would wheel a carriage with one hand and hold a Tehillim in the other, while praying one simple prayer: “Just let this child know that there is an Eibeshter in the world.”

Teaching Torah was one of the worst crimes one could commit in the USSR, and countless brave melamdim lost their lives for doing so. Sometimes they were just taken away by the KGB, never to be seen or heard from again, with no word of their fate sent to their families. Yet even in those days, the hearts of the Chabad chassidim burned with the fire of a mission.

Rav Yudkin told the following story, which some of those close to him believe might have been his own experience. “A rebbi was teaching a group of young boys when a KGB raid took place. He ran for his life out into the yard, but there was no exit. There was nowhere to hide besides the outhouse pit, so he climbed in there, ducked down, and hid until they had given up hunting for him. After he emerged, he washed and changed his clothing but the foul odor still clung to him.

“Later that day, at Minchah, the other men didn’t want to daven with him and asked him to leave because of the terrible smell. But the rav, who understood what had happened, told them, ‘This is not a foul odor. This is the odor of Gan Eden.’ ”

Marching Orders

In 1969, the Yudkin family received permission to leave Russia, and moved to Eretz Yisrael, where the younger two of their six children were born. Reb Zalman began to work in a textile factory, but parnassah was a giant struggle. He saved up, dollar by dollar, until he had enough to travel to New York to the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

At a yechidus with the Rebbe, Reb Zalman received his marching orders. The Rebbe instructed him to start fundraising for the Chabad mosdos, and gave him a few instructions: Only go to places where you have a good achsanya [host], accept any donation with a full heart and don’t push anyone to give more, work on a fixed salary, and never agree to do any shtick for people with tzedakah money. These became guiding principles. Whether someone gave $1,000 or 50 cents, Reb Zalman would reply with the same string of warm brachos.

Rav Zalman’s first fundraising trip was to England. The Rebbe directed him there to a well-known Chabad donor who had opened a knitwear factory. After that, he traveled around the world.

The Yudkins lived in Eretz Yisrael, but Reb Zalman’s work took him far from home for long periods of time. At first, he would travel to Europe, too, but as he got older, his fundraising centered on North America. Being away from his family for so long wasn’t simple, but Reb Zalman never deserted the Rebbe’s shlichus.

Tuvya Yudkin, Reb Zalman’s son who lives in Kfar Chabad, says he doesn’t have much to share about his father, since most of the stories remained untold. He does say that Reb Leibel Groner, the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s personal secretary, told him that the Rebbe would stand for Reb Zalman when he went into a yechidus (a private audience), out of respect for what he’d been through.

Tuvya remembers that when the family lived in Kiryat Malachi, the Georgian community there, which had no Kohanim, asked his father to daven with them so he could give Bircas Kohanim, which is a daily privilege in Eretz Yisrael. “We children didn’t like going to the Georgian shul, because it wasn’t our nusach,” he shares. “We wanted to daven in the Chabad shul, so my father asked the Rebbe what to do. The Rebbe told him to daven with the Georgians, adding, “And I take achrayus that your children won’t lose out.”

Another weighty dilemma came up when Tuvya turned 13. His bar mitzvah fell in Shevat, and Rav Yudkin, who was then based in Crown Heights, asked the Rebbe if he should travel back to Eretz Yisrael to be with his son. He was concerned that this would seriously affect his work, because donors give especially generously in Adar. The Rebbe’s response reflected the significance he attributed to Rav Yudkin’s work: “You stay, and I'll take the bar mitzvah on my shoulders,” he said.

Tuvya reflects that although he was worried about being embarrassed about his father’s absence, once the Rebbe took personal responsibility for him, he felt good about it. “I felt like, wow, I’m in with the Rebbe.”

Food for the Soul

During his time in Russia, Rav Yudkin had made a neder that he would no longer eat meat or chicken. Although this meant his visits involved specific food preparation, people still loved hosting Rav Yudkin. He was a gentle, eidel man, with a sense of humor, but beyond that, all his hosts agree that they sensed they were hosting someone special, a Yid with a very pure soul.

For Mrs. F., it started when her husband brought Rav Yudkin home from shul with him for breakfast. (Her sister had hosted Rav Yudkin for years, before she moved away from the US.) Rav Yudkin asked if she had “bilkes” — small rolls. “He was always welcome, of course, no one could have anything against such a man. Such an anav, and so gentle. He would knock on the door, and if asked who was there, he’d just say simply ‘Zalman, Zalman….’

“Everything was “Yah, yah” [yes] in his Russian Yiddish. When asked if he needed anything more, the answer was “Ich darf nisht gurnisht — I don’t need anything.” I used to put sugar in his hot drinks, but he asked me to stop, because he didn’t need it.”

Like all Rav Yudkin’s hosts, Mrs. R. was aware of his dietary restrictions and would graciously prepare to serve her guest according to his specific needs. “He would let me know that day or the day before that he was coming, and I would stock up on avocados and Israeli cheese products. Although his diet was very limited, no fleishigs at all, Rav Yudkin ate healthfully. It didn’t bother him at all to eat the same things all the time. He’d eat salmon and vegetable soup in our house, and I’d cook various pareve things, and that was it.”

Years later, when Rav Yudkin became unwell, Mrs. F. would send packages of food to his apartment in Crown Heights. He was on a strict diet and, as always, was very thankful.

For Pesach, Rav Yudkin was even more careful with his diet. In the later years, when he was alone due to the Covid pandemic and his own frail health, Mrs. F. would prepare a carton of cooked food, carefully double wrapped, and send it to Rav Yudkin’s apartment for him. For the last two years, he asked her not to use any spices or condiments in his Pesach food, only salt.

“I explained that I had already prepared gefilte fish with sugar. He checked that I had seen the fish still alive and had been present when it was prepared, then he said, ‘If you were there, it’s fine,’ and he ate it. The last Pesach of his life, he told me he doesn’t want any cake, any sugar.

“You can’t just have soup and compote!” I protested.

“But he was adamant. ‘I can live without all this for eight days, nothing is going to happen.’

“I bought more raw ground fish, seasoned it with only salt, and blended it with a hand blender. Nothing went into that gefilte fish I made for him, no sugar, no eggs, no binding agent, just pure fish and salt. I made a roll, cooked it, and fearfully tasted it. You know what? It was absolutely delicious.

“His dietary limitations were all with humor. My husband went to visit, and always found him with a Chumash and Tehillim open. He asked Rav Yudkin what he could eat, and with a laugh, he’d always reply, ‘Ich es alles vus der Eibeshter hot gegeben un mir ken machen a bruchah.’ ” [I eat everything that the Eibishter gave and one can make a brachah on it.]

Leaving Blessing

Rav Yudkin was a Kohein, and people loved to get his brachos. He told Mrs. F. that he davened for her family every day. When her children in shidduchim began to get a little older, he told them, “At the end of the tunnel there is light. You just have to believe.” And when they got engaged and married, he was delighted.

It was not only the people whom he stayed with who were the beneficiaries of his brachos. When Rav Yudkin would enter a house to collect, the mother of the home would sometimes bring her little children over to get a brachah from him. “He was the kind of person you could talk to, with no airs about him,” Mrs. R. reminisces. “So people shared their problems with him.”

One day, someone came over to talk to Rav Yudkin at the home, and they sat outside together for a long time. Rav Yudkin came into the house afterward and commented, “He thinks I am a rebbe.” The next day, the man came back and informed him that he had experienced a yeshuah.

Mr. Shauly Katz from Monsey was one of those closest to Rav Yudkin. He would host him for weeks at a time for about 20 years, and would drive him around in the evenings, from about 5 p.m. to 11 p.m. He says Rav Yudkin brought brachah to his business. “We had hired a new worker, who was being trained in by others, also non-Jews,” Mr. Katz remembers. “Rav Yudkin called, and she put the call on hold and told the others that she could not make out a word. Right away, they told her, ‘That’s the Little Rabbi.’

“I then overheard them saying, ‘When this Little Rabbi comes, every now and then, get ready, we are going to get crazy busy. You will not have a minute to breathe during the day.’

“I was busy chauffeuring Rav Yudkin, but these non-Jews noticed how orders began to come in thick and fast during this time!”

Rav Yudkin continued his mission well past retirement age, but Covid ushered in a new, difficult era for him. His wife had passed away a few years before, and he had relocated to Crown Heights. Elderly and frail, he had to self-isolate to evade catching the virus. At first, he would still make an early morning visit to the mikveh, but soon, he could no longer go to shul or mikveh, no longer fundraise, and no longer spend Shabbos with families he was close to. Grandchildren and a few friends came in to visit, but otherwise, he spent hours upon hours alone.

So many wondered how an elderly person in his nineties had the drive to keep going on the Rebbe’s mission, amassing funds for the Chabad mosdos and their kiruv work. But Shauly Katz comments that maybe his determination to keep going was fueled by an understanding of what his mission really was. It wasn’t only about collecting money for yeshivos; it was about spreading chizuk and brachah to the homes of thousands of donors, who became recipients of his warm blessings.

“I saw Reb Zalman go into a home and ask for a fruit or vegetable to eat, when I knew he had just eaten supper. Soon I figured it out — he wanted to make a brachah there, so he would be able to leave a brachah behind him,” says Mr. Katz.

“He told me as much: ‘I make a brachah in the house, then I leave a brachah there.’ I saw him help people with parnassah in this way, and eventually I started to take him to the homes of people who were struggling so that he could bentsh them and help them.”

From Satmar and Klausenburg chassidim to litvish Jews and the Sephardic Jews of Flatbush, this Latvian Chabad chassid and Holocaust survivor was a beloved and respected figure as he went on his rounds. Although he viewed himself and spoke of himself as an am ha'aretz since Stalin had ensured he could not learn in a yeshivah in his youth, Rav Yudkin was actually well-versed in Torah and chassidus. But above all else, you could sense his sincerity and purity, and the suffering he had endured for his Yiddishkeit.

Perhaps Mrs. R. sums it up best. “We knew he was a holy Jew.”

Thank you to Reb Shauly Katz for his assistance with this article.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1061)

Oops! We could not locate your form.