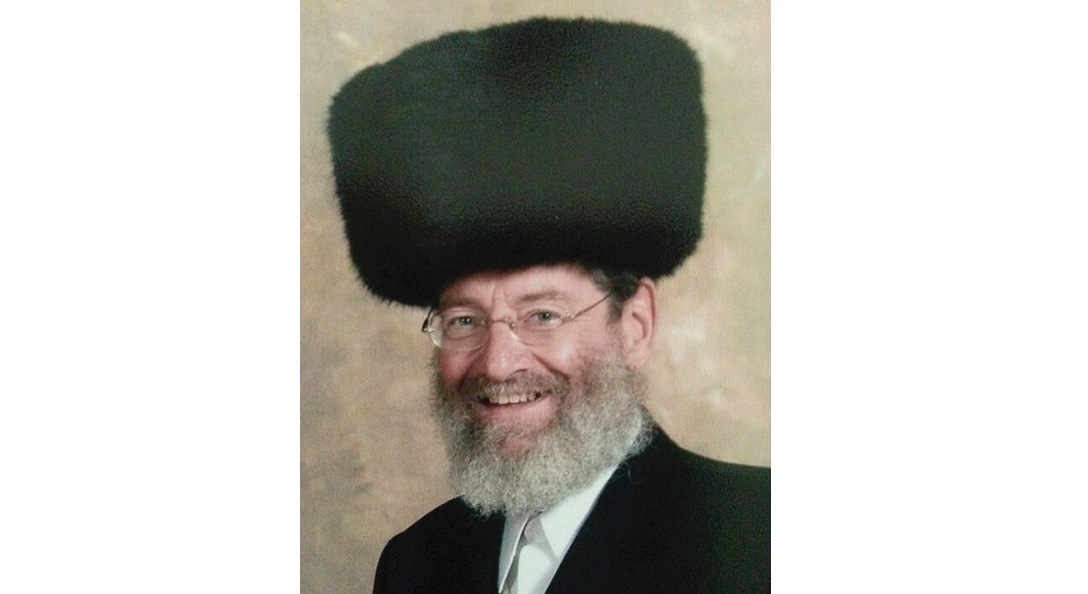

My Uncle, My Friend

{ Reb Yitzchok ben Reb Yisroel Tzvi }

R

emember? I really don’t forget very often.

What he taught me, what he did for me, what he was to me.

Growing up, I knew that my mother’s brother was a big talmid chacham in Yerushalayim, but that just made him more distant, less approachable.

Until I came to learn in Eretz Yisrael.

From the first time I walked into his Har Nof apartment — which felt like home if only because of the familiar smells from the kitchen, the music, the laughter — I understood what Chazal meant when they say that one who learns Torah lishmah “is called a friend.”

My uncle might just have been the best friend I ever had. Curious, fascinating, brilliant, generous, funny, elevated, kind — and never, ever boring.

The table at which he learned saw all the parables — thirsty at water’s edge, drowning and crying out for a raft, freezing and desperate for shelter — in the way he embraced the Gemara, devoured it, challenged it, submitted to it.

If you stepped in and saw him learning, you felt like you were interrupting something; yet if he looked up and saw you, you became the sugya. His eyes would open even bigger, a new layer of interest.

“How are you?”

He never lied. So when he said “It’s great to see you,” you felt like someone worth seeing.

The more broken the person, the deeper the relationship with him. He was a healer in the way he made you feel, a little island where discarded people and ideas washed up to enjoy a new life.

He had three great loves in his life. Torah was the first. It consumed him. He had an urgent need to understand Torah, desperate for the ever-elusive breakthrough. He would sometimes confide, “I’m an am ha’aretz, you think I’ll ever understand anything? You think I’ll ever know how ‘zika’ works? What a shtar is?”

He told one of his children: “The Ribbono shel Olam isn’t karg, cheap, with His money; anyone can get it if they want. Just look around how many people have it. He is karg with His Torah, that’s much more tayer to Him, that’s why so few people have it.”

He didn’t make birchos haTorah, because he never stopped learning. Even in those years when he slept at night — not much, and not for long — he would often wake up, hurry to the seforim shelf, look something up and go back to bed. He wasn’t meisiach daas from learning. On Shabbos, however, he would make birchos haTorah for the week ahead — because on Shabbos, one perceives a new Torah.

He loved the Torah, but he wouldn’t kiss the sefer Torah. When the aron kodesh was opened, he would rise and follow the scroll with his eyes, radiating reverence and awe. But he couldn’t approach it; he felt too small, too insignificant.

His second great love was Eretz Yisrael. The only time he got angry — actually growing uncharacteristically angry and giving me mussar! — was when we were walking down the street near Zichron Moshe and I dropped a wrapper on the ground. He looked at me in horror. “Yerushalayim? Don’t you ever dirty Eretz Yisrael!” (Eretz Yisrael is a kallah, he would say, that’s why the meraglim had to go see her first...)

His third great love was his family. His wife enabled him to learn Torah, giving him the greatest gift of all, and his respect for her bordered on reverence. (Money, he often told me, is no cheshbon when it comes to honoring your wife. The Gemara says you get rich if you’re nice to your wife, he would say. What difference does it make how much it costs to please or honor her if displaying respect for her will yield greater wealth? It was a basic equation.)

He didn’t just love his children, he understood his children. Whatever they did or didn’t do was in the context of that understanding. One of the last brachos he gave, to a family member who asked for a brachah for nachas from her children, was this: “You should love your children unconditionally. That’s a much bigger brachah.”

Until he took ill, he was the most “alive” person I’ve ever known.

The last decade was rough. He was sicker and sicker, frail, tormented. He would transcend his pain if people were speaking in learning, but it was clear that he was fading fast. Every time I left Eretz Yisrael he would say, “Don’t worry, we’ll still see each other.” Except for the last time. So I knew it meant goodbye.

He wasn’t worried, though. He assured me he was ready for the Next World, bursting with kushyos that begged answers, eager for the shiur he would hear from Rav Akiva Eiger.

Meforshim ask why Yizkor is recited on Yom Tov, a time when mourning is forbidden.

When I remember my uncle, I understand. Life in proximity to him was so rich, so colorful, so delightful. The chance to remember, to escape reality for a moment and grasp at images, recapture conversations stored away, are a Yom Tov of their own.

I will never forget my uncle, my rebbi, my rebbi, my friend, Reb Yitzchok ben Reb Yisroel Tzvi Gepner, and the blessings he brought to the lives of his family, his friends, his talmidim.

Gut Yom Tov, dear uncle. I miss you.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 577)

Oops! We could not locate your form.