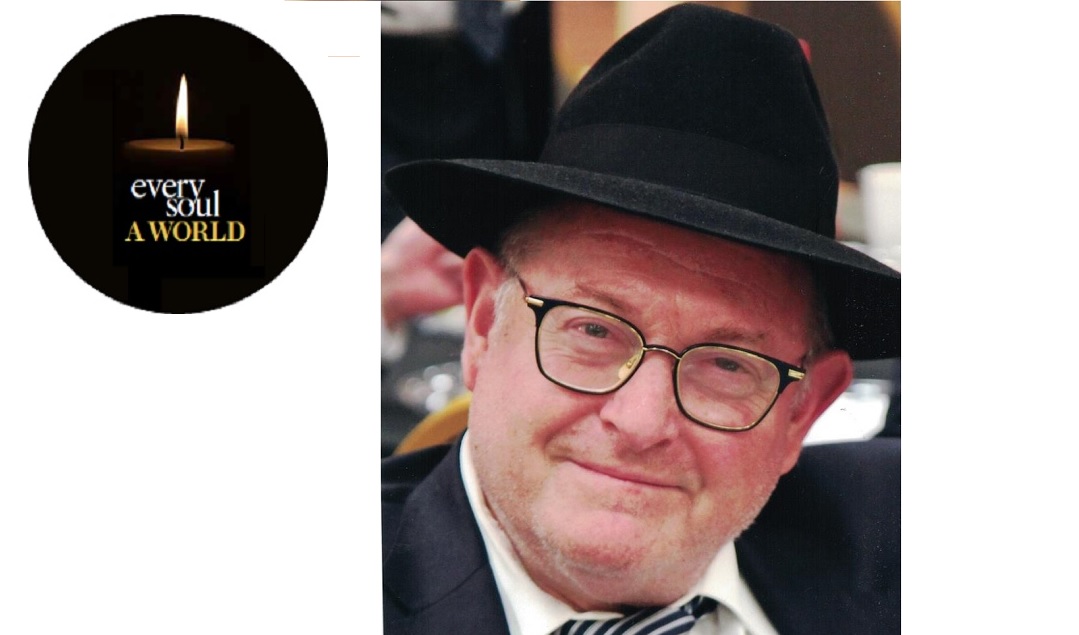

Mr. Meir Loebenstein

| June 9, 2020Beneath the public eye, there was more, a current of chesed that laced through his days, almost unnoticed

cousin of the Loebensteins called on Chol Hamoed Pesach from Switzerland. Was Meir okay? It was the first time in decades that he hadn’t received a Gut Yom Tov phone call from him.

He wasn’t. Always fit and healthy, and just 59 years old, Meir was fighting for his life in the COVID ICU.

All his life, Meir Loebenstein had been there for others, as if blessed with a sixth sense to know what they needed, and get it done. Meir Loebenstein was that caring neighbor who didn’t need to be asked, didn’t talk, just took his neighbors’ excess garbage to the city dump after a simchah. Who without being asked, personally delivered 80 chairs to a friend who was hosting a sheva brachos. On an icy December night in his hometown of Manchester, he showed up at the hospital with chocolate, food, and a Chumash for an acquaintance who had rushed to the emergency room with an ill child. He then drove him home to pick up his own car.

A genius at making others feel cared for, he called his widowed sister daily, his aunts and uncles weekly, and all relatives when they celebrated simchahs. Even family members in Australia were not exempt. One aunt, who had suffered a stroke and was in a nursing home for years, couldn’t even hold the phone. But each week, the nursing staff brought the phone to her, saying, “You have a call from Meir in England.” Those present saw her face light up — she had not been forgotten. If, when Meir called her on Thursday, his aunt was sleeping or unavailable, he would call again on Friday. Australia being ten hours ahead of England, and Shabbos coming in early, this could mean getting up at four a.m. on Friday morning to wish his aunt a good Shabbos. Not a problem.

Quietly and humbly, he regularly visited the housebound and called the lonely. Not even his wife knew how many lives he brightened each week with a friendly phone call. And this care and courtesy for the elderly also extended to a non-Jewish woman living on their predominantly Jewish block, for whom he picked up groceries.

He had learned in Sunderland Yeshivah as a bochur, and so Meir kept in touch with his roshei yeshivah, Rav Zecharia Gelley and Dayan Chanoch Ehrentrau, always asking hadrachah and she’eilos from his own rebbeim. Characteristically, his hakaras hatov and sensitivity included calling Rebbetzin Gelley regularly after the Rav’s petirah.

“When I arrived from Ireland to Sunderland Yeshivah for the first time, I did not know anyone there,” recalls Rabbi Yonason Yodaiken, principal of Manchester’s Yesoiday Hatorah Jewish Day School. “I was very anxious, until a bochur ran over to me with a big smile, took my bags, brought me to my room, went downstairs to get me hot soup, and then introduced me to the rosh yeshivah. The next morning, I noticed that the bochur who had welcomed me was the gabbai — Meir Loebenstein. He gave me an aliyah, and throughout the time I was in yeshivah with him, he did everything he could to make me feel at home there. Roll on a few years, and I was welcoming his children to our school in Manchester. The evening before every term began, for a few decades, Reb Meir called me with his special warm brachos for the year ahead.”

Shidduchim and Marriage

Meir returned home from learning in Sunderland Yeshivah and then Gateshead, and began to work in Manchester. While he was in shidduchim, shadchanim suggested he consider moving to London. Many American and European girls would consider a boy from London, but who would want to move to the provincial, small community of Manchester? Meir stuck to his principles — he was not going to move away from his parents, because he wanted to be there for them. At 29, he married Bracha Benjamin from Lucerne, who gladly moved to Manchester and supported Meir’s desire to be available, at his parents’ beck and call, day and night. As they aged, he would go in after Shacharis to prepare their coffee and siddurim, then again many times throughout the day. In later years, he escorted his father to daven and stood at his side for every tefillah. On Motzaei Shabbos, he was there to fold the tablecloths and put away the silverware. When his mother was alone, he did everything he could, with incredible patience until, for the last few years, she moved into the house next door so that Meir and Bracha would always be there for her.

The home they built was a beautiful one, with values, warmth, and happy children. Meir and Bracha hosted guests royally, from seminary girls who felt right at home to young nieces and nephews who recall that, “Uncle Meir made sure we had an amazing time whenever we were in Manchester. The house was full of fun and excitement and he was the funny uncle. He even knew the names of our dolls.” Whatever hour of day or night the guests were leaving, it was no trouble for him to drive to the airport or train station. He did not ask, he just went ahead and did it. One lady arrived late for a wedding in Manchester and went straight to the hall. She was staying at the Loebensteins. Unasked, intent on saving her from schlepping her suitcase and worrying about its safety all evening, Meir came to pick it up from the hall and placed it in the guestroom.

His coworker recalls having a carpool issue. “Meir said, ‘I’m doing carpool today, does your Miri have a ride?” At first I believed him, later she told me she was the only kid in the car. He was doing carpool for my Miri alone.” In fact, rides were a chesed specialty. The Loebenstein minivan would even make a U-turn or a special journey to pick someone up. In the office, although a senior member of the company he worked for, Meir brought others drinks and did the jobs others would diplomatically shy away from — taking out the garbage when required, and assembling IKEA desks for new employees. And no matter how long he worked for the company, he referred to all female staff as Mrs. or Miss.

The Unforgettable Mi Shebeirach

Meir Loebenstein was raised in Manchester’s Adass Yeshurun shul, and he never left it.

The shul was his second home; he came early to daven every tefillah and often served as gabbai, delighting in running over to newcomers to show them to available seats (often, to his own seat) and bring them siddurim of their preferred nusach. One fellow mispallel wrote: “Meir paid good money for four seats in shul, for him and his boys. But I can count on my fingers how often I saw him actually sitting on his own seat.” All this somehow happened without him speaking, because he never spoke in shul.

It was so important to him that other people should feel comfortable there, especially elderly members. For one old lady, he went upstairs to the ezras nashim before davening began, and prepared a specific comfortable chair and siddur. His kavod for rabbanim was absolute. When a respected rav who lived near Adass Yeshurun started to daven there due to age and infirmity, Meir would have been kind just to ensure that the rav had a nice seat. But he would go each Shabbos to bring him to shul, and escort him home afterward, like a dutiful son.

He would personally bring chairs for the seminary girls who attended on Yamim Noraim and had a sixth sense for when a woman was trying to call her husband out of shul. He personally polished the silver of the shul’s sifrei Torah. On Thursdays, Meir would slip into the shul, get out the vacuum cleaner, and vacuum the shul’s carpets and the steps to the aron kodesh. He felt it was not kavod for the beis knesses to be cleaned by the non-Jewish cleaning crew. He was a doer and a real Yekkeh. Simchas Torah, after the seudah, he headed back to shul with a broom, sweeping every last candy wrapper and crumb from the house of Hashem.

Once, he noticed two individuals trying to best each other over an ArtScroll siddur, one trying to put it away in his desk so he’d have it for next time, the other one putting it back on the shelf. Meir went to buy another one out of his own pocket, and placed it in this man’s desk.

He lived with a youthful joie de vivre, but certainly did not wear his emotions on his sleeve. Yet Meir’s Mi Shebeirachs became a legend. Even on a regular Monday or Thursday morning, the caring in his heart overflowed. He couldn’t hide it. That set formula of blessing was far from a rote recital in Adass Yeshurun. Coming from Reb Meir Loebenstein, it was a warmly recited, sincere prayer for another Yid, for his family, his success, his children. Dozens upon dozens of letters received by the family mention the Mi Shebeirachs that regulars and visitors loved receiving, a caress of care from someone who sometimes did not even know their family. On the Yamim Noraim, the Mi Shebeirachs entered another league entirely.

A Yekkeh through and through, a wonderful husband and father and an upright balabos with fixed learning sedarim, Reb Meir’s life was an example of yashrus to his community. But beneath the public eye, there was more, a current of chesed that laced through his days, almost unnoticed. His father had been active on the chevra kaddisha, and when he was no longer able to continue, Meir joined. His company allowed him to leave the office when called, and in characteristic fashion, he would quietly tell coworkers that he had “to go out and see to something,” later returning without a word. A coworker did not know that Meir was on the chevra kaddisha until he joined himself, seven years later. For that was Reb Meir — do what’s right, and do for others, with no fuss or fanfare.

VIEW/DOWNLOAD PDF VERSION

Oops! We could not locate your form.