Moment by Temporary Moment

This moment’s poverty or wealth says nothing about the next moment. Neither despair nor arrogance ought to reside in our hearts — ever!

ON

Yom Kippur 50 years ago, I was an American bochur davening in the Mir Yeshivah when the sirens went off. It was not until quite a few days later that the extent of the terrible devastation became known. But the shock was immediate: It can’t be, it just can’t be.

I had come to Israel three years earlier. Just three years before my arrival, during the Six Day War, the Arab armies had been defeated for once and for all. It would be at least a thousand years until they could even have the audacity to start up with us.

I recall a few months after I came, I saw a new building going up, with a space designated for a bomb shelter. I was puzzled. I asked someone, why do we still need these? He shrugged and muttered something about outdated regulations.

Fifty years have gone by, and once again, we are at an impossible moment.

There is so much emotion to grapple with: The Yom Tov that turned to mourning for so many. The terrible decisions that may have to be made about the hostages. The young boys who will be entering the hell of Gaza, and their families who will be in excruciating tension for as long as their children are there. Their nights and days will be one long nightmare, faces turning pale at every knock on the door and every buzz of the phone.

There is so much nesias ol that we need to generate. So much tefillos harabim, and so much tikkun hamaaseh. But as I was dancing hakafos, my mind kept going back to that fateful Yom Kippur 50 years ago, and how I was sure that never again would I think, “It can’t be.”

So let us ponder that mood of self-assuredness, of smugness and complacency. On the level of behavioral science, this is a well-known phenomenon that affects everyone — from the businessman, to the soldier, to the criminal, and so on and so on. Success breeds a sense of “this is natural and automatic,” and the person becomes more careless and reckless. This is what Shlomo tells us explicitly as possible: “Before collapse comes pride; before failure, haughtiness of spirit” (Mishlei 16:18).

But I’d like to understand the ruchniyus manifestation of this attitude, and where it stems from.

The Zohar states in parshas Naso, “A person travels through this world, and he feels that it will be his forever and that he will remain there for all generations to come.” The Zohar is revealing to us an extraordinary aspect of the human sense of things.

The ardent believer prays mightily to Hashem to acquire something, knowing that Hashem is the source of all. Yet once the person has acquired or achieved anything, he feels that it is rightfully his unless Hashem chooses to take it away from him. Yes, he acknowledges that the actual acquisition comes from Hashem, and he knows that Hashem can take it back, but in the present moment, the feeling is that it’s naturally mine.

Perhaps this was what was meant by Bar Koziba, who, before setting out for battle, turned to Hashem and proclaimed, “Don’t help us, just don’t hinder us” (Midrash Rabbah on Eichah 2:4). Bar Koziba could not have been a crass disbeliever — Rabi Akiva supported him and possibly believed that he was Mashiach. He certainly understood that might and strength came to him from Hashem. But once gained, he felt that strength was naturally his, and that in order to succeed in battle he merely needed that Hashem not interfere with the natural deployment of that strength.

This dynamic is often described in the Torah as Bnei Yisrael “becoming fat” and then denying Hashem. And it is so true of us today in so many different ways.

WE all recognize that Hashem gave us life, but we think the good health that we enjoy is ours. Certainly Hashem can chas v’shalom rock our health, but so long as He doesn’t, we think it’s ours. The same attitude holds true for the wealth that we have accumulated, and it is true of our ruchniyus and so much more.

This runs counter to the middah of bitachon. We tend to think about bitachon when we’re in difficult situations and hope for the best. Many times we say the right words, and perhaps we emotionally latch on to them so that we don’t despair. But bitachon is doubly necessary when dealing with what we have actually succeeded in acquiring.

We need to genuinely feel and believe that we have whatever we do because Hashem is allowing us to have it at this present moment — and there is nothing about our having it that makes it ours in any permanent way.

The appropriate attitude is expressed in our daily davening: “hamechadeish b’tuvo b’chol yom tamid;” Hashem is constantly renewing the world. We tend to understand this as some sort of mystical reference, that Hashem is constantly repeating “let there be light” in the higher worlds. As such, it is an abstract philosophy meaning very little to us practically.

But if we translate it to our day-to-day life, it is the greatest test of emunah and bitachon. It means that whether our bank account is utterly empty or bursting with nine-digit figures, our situation is utterly the same. This moment’s poverty or wealth says nothing about the next moment. Neither despair nor arrogance ought to reside in our hearts — ever!

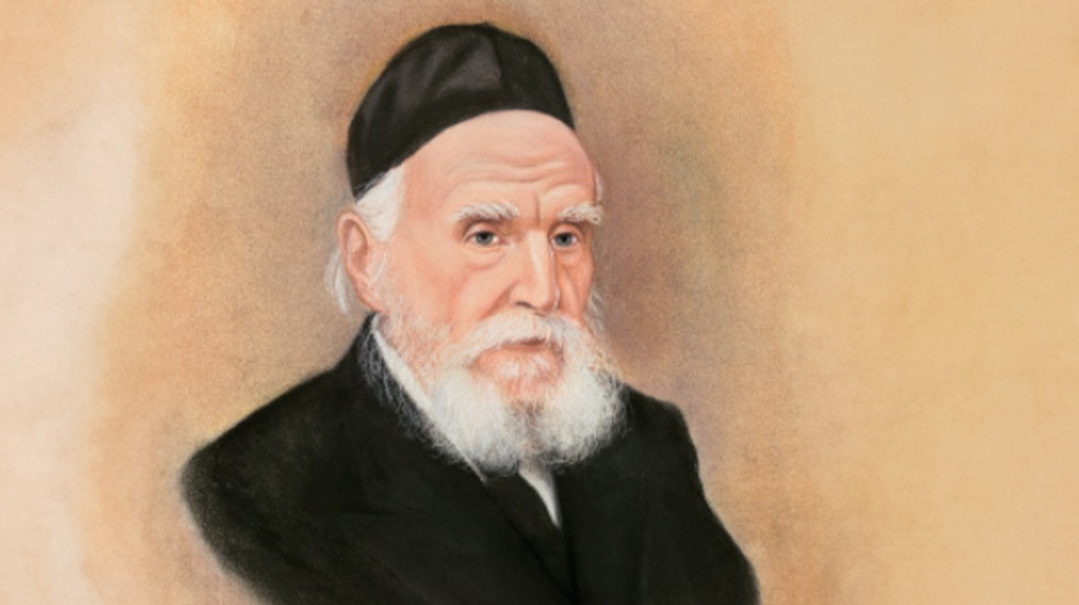

I recall a year when the enrollment in the Mir Yeshivah increased dramatically. There was a general sense of elation. But when Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz got up to say the first shmuess of the zman, he had a different perspective. When he looked around and saw the overflow crowd, he spoke of trepidation; of the dangers of being overtaken by one’s sense of success.

Baruch Hashem, Klal Yisrael has so much today. There are material possessions and extraordinary ruchniyus accomplishments. But woe unto us if even for a moment we feel smug and complacent, thinking that if we have it, then it has become ours as a given.

The succah is an ultimate sign of bitachon. For even as we are sitting in a home, we can still see the sky peeking through the holes. A brick-and-mortar home protects a person, but it also shuts out Hashem. A succah, in contrast, is indeed a house — but a temporary one. It can last for a long time, but each moment of its existence is a temporary moment.

Would that we be zocheh to live Succos in its full sense of diras arai, and we’ll have Shemini Atzeres of simchah and never again of the devastation that we lived through this week.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 981)

Oops! We could not locate your form.