Give Like Gottesman

| March 12, 2024If we are going to dream, let’s envision what frum donors — not others — can do

Photo: AP Newsroom

Years ago, a leading rosh yeshivah told me that he drew inspiration from Cal Ripken Jr. He felt that he should be just as devoted to his talmidim and harbatzas haTorah as Mr. Ripken was to baseball when he played in 2,632 consecutive games.

I can’t say that this rosh yeshivah never missed a shiur in 17 years — professional athletes get many more days off than roshei yeshivah and aren’t expected to also raise the funds necessary to keep their institutions afloat — but I do know that more than 25 years later the example of Cal Ripken still affects his attitude about missing a shiur.

This came to mind recently with the news of Ruth Gottesman’s billion-dollar donation to the Albert Einstein College of Medicine to allow students to attend tuition free. Before the Gottesman gift, medical students there had to pay more than $70,000 annually, and most left school with hundreds of thousands of dollars in student loans.

In conversations and online, I repeatedly heard versions of If only.

If only Dr. Gottesman had contributed to yeshivos so that their students could attend tuition free. If only Dr. Gottesman had supported schools and other programs for unaffiliated Jews, so that they could be exposed to the beauty of Judaism. If only Dr. Gottesman had undertaken to alleviate the financial burden facing those who devote their lives to the Jewish community rather than to subsidize future medical students.

This lament misses the mark. We would be better served by pondering a different set of If onlys.

If only those with the means to do so within our own community were to make similarly transformative contributions to our essential institutions. If only there were an Orthodox version of the Giving Pledge. If only certain initiatives vital to our community were properly endowed rather than always scrambling for funds.

If we are going to dream, let’s envision what frum donors — not others — can do.

We can dream bigger even as we appreciate our community’s unparalleled charitable instinct and giving to institutions and individuals both here and in Eretz Yisrael in support of Torah and chesed.

There are understandable reasons why Gottesman-type endowments are unheard of in our community. For starters, to a degree not seen outside of the frum world, our wealthiest donors regularly contribute substantial sums — without fanfare or publicity — for the ongoing operating support of our biggest institutions.

There is also the fact that those within the Orthodox community are generally confident of their doros and the values and way of life of their descendants. They are not worried about what causes future generations will spend the family fortune on, and so lack the motivation that others exhibit in making enormous later-in-life contributions.

We also need to acknowledge that many of our institutions do not have the governance or succession planning that are taken for granted elsewhere, making it unrealistic to expect donors to contribute large sums for future use.

Yet for those who have the resources, there are even better reasons to make transformative charitable donations.

In my youth, the name Joseph Gruss became synonymous with Jewish education. He built yeshivah buildings and underwrote programs to assist yeshivah faculty with insurance and other benefits that were far ahead of their time.

Later, Zalman Bernstein endowed the Avi Chai Foundation that funded programs supporting Jewish education, including one that participated meaningfully in the construction of more than 150 yeshivah and day school buildings across the country.

In the post–World War II era that saw an explosion of new day schools created throughout the United States, Stephen Klein personally guaranteed the financial obligations undertaken by the lay leaders in those communities. I don’t know how often he had to make good on them, but the peace of mind those guarantees afforded to activists gave them the confidence necessary to open many new Jewish schools.

None of this is meant to suggest specifically what the wealthiest among us should devote their charitable resources to. Some may want to create a network of kollels, while others will prioritize institutions that can capitalize on the renewed interest in Jewish life among the nonobservant that has been sparked by the atrocities of October 7 and the anti-Semitism that has followed.

Some might choose to devote their enormous resources to elementary and high schools, thereby alleviating the burden on both overtaxed middle-class families and underpaid rebbeim and morahs, while also enhancing the chinuch students receive. Given the crushing burden of housing prices both here and in Israel, someone with the financial ability and foresight could create new neighborhoods where young families can build healthy lives and communities.

Still others may choose to focus on strengthening and building chassidishe communities and institutions, or those servicing the Modern Orthodox community.

The possibilities are endless, limited only by the generosity, imagination, and determination of donors. What is most important is not what causes they choose but rather that they choose a cause.

There is also a spiritual need for a generation that displays limitless ambition in matters of commerce to bring a similarly ambitious sky-is-the-limit approach to tzedakah.

The Gemara in Megillah (13b) explains that Klal Yisrael’s giving the machatzis hashekel counteracted Haman’s offer of 10,000 kikar kesef to Achashveirosh. But why did Haman’s offer of payment have a Heavenly force that demanded a response?

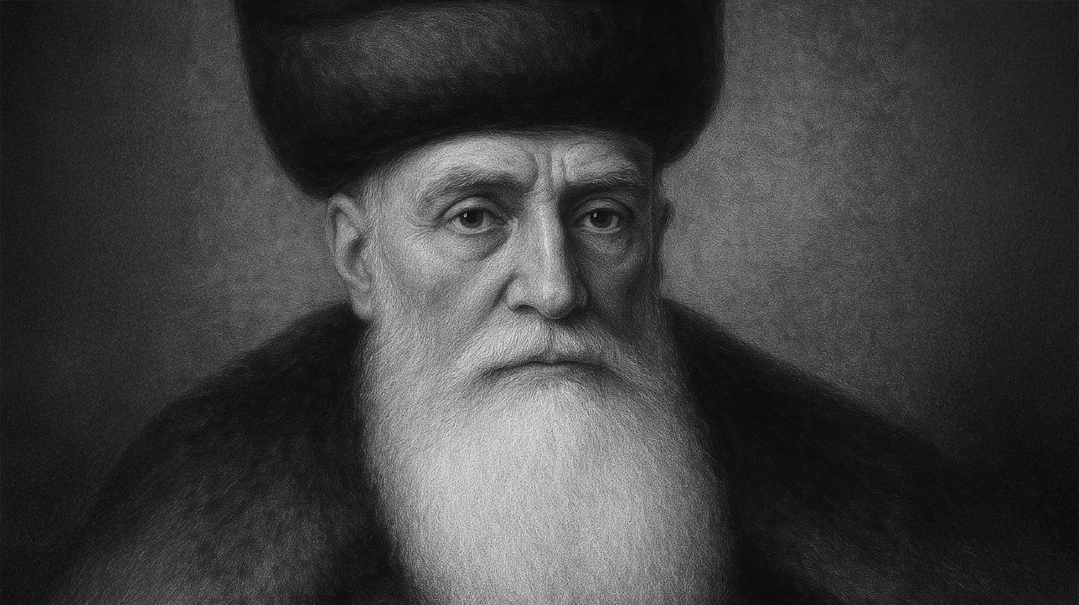

Rav Sholom Schwadron ztz”l answers by reference to a midrash in parshas Terumah that says the 10,000 kikar kesef was Haman’s entire fortune. Haman’s willingness to dedicate all of his resources — his mesirus nefesh, if you will — to accomplish his goal needed to be counteracted by the Jewish People. Where was their dedication, their devotion, their sacrifice? The annual machatzis hashekel was the answer.

Rav Moshe Feinstein ztz”l makes a similar point in Darash Moshe. Rashi in parshas Balak quotes the Midrash that HaKadosh Baruch Hu told Bilaam that the zeal he thought would allow him to succeed in harming Klal Yisrael had long ago been manifest by Avraham Avinu as he set out for the Akeidah.

The same question arises. Why did Bilaam’s conduct need to be counteracted by Avraham’s earlier action? Again, the answer is that the dedication shown by Bilaam created a spiritual force that demanded Klal Yisrael’s even greater fidelity to Hashem.

Rav Moshe goes further, explaining that the degree to which a society devotes itself to financial pursuits impacts the lengths to which those supporting Torah and mitzvos must go to aid and assist their avodas hakodesh. More is demanded of them, and Klal Yisrael is called to account for any lesser commitment in service of Hashem.

Properly understood then, Ruth Gottesman’s generosity not only should inspire greater charitable giving but also requires us to rise to even greater heights of tzedakah.

These musings may seem ill timed given the uncertain economic climate. In particular, several industries that have traditionally been sources of great wealth are hurting. Yet that has ever been the story of the Jewish People. Eras of success and comfort are followed by challenging times. Historically, we have been the victims of persecution, unfair taxation, expulsion, and worse. Perhaps the lesson is to use the resources we have been given while the opportunity to do so still exists.

Above all else, let us daven that HaKadosh Baruch Hu provide parnassah and shefa to all of Klal Yisrael. And may those who are the biggest beneficiaries of His munificence also be endowed with the wisdom, vision, and courage to emulate Ruth Gottesman’s magnificent commitment to giving it away.—

Avi Schick is a partner at Troutman Pepper and the president of the Rabbi Jacob Joseph School.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1003)

Oops! We could not locate your form.