Last Woman Standing

91-year-old Margalit Zinati is the final guard of ancient Peki'in

Photos: Rabbi Ephraim Schwartz, Beit Zinati archives

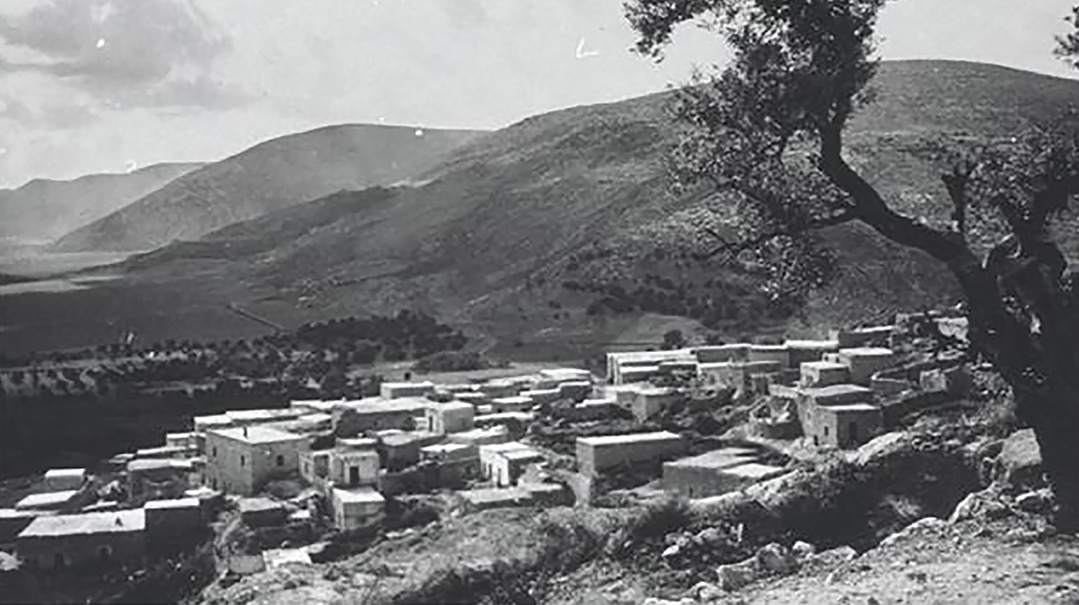

Peki’in, today a mixed Christian, Muslim, and Druze village, has the distinction of being the only city with a contiguous Jewish settlement from the time several families of Kohanim fled here during the siege of the Second Beis Hamikdash until the present. In the 1920s, Peki’in was “discovered” by Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, a historian and researcher who would later become Israel’s longest-serving president — and yes, it’s his picture that’s on the front of those 100-shekel bills. But while Ben-Zvi was so overwhelmed by the Jewish families living there who made up an unbroken chain since the Churban that he became their patron, he would undoubtedly be broken-hearted today, knowing that the one remaining Jew in Peki’in is a 91-year-old woman named Margalit Zinati, the last and final link in the chain.

Margalit, who was born in 1931, is the devoted daughter of Peki’in’s last holdout Jewish family (the town’s Jews fled during the Arab riots of the late 1930s, and only the Zinati family returned). Early on she decided not to marry, which would have meant leaving the village, and instead threw her lot in with her parents and remained in the town to care for them, guard the family plots and fields, and protect the holy places. Now, as Margalit’s age creeps past 90 with no children of her own, it seems the curtain will finally be drawn over this primeval Jewish community.

No Greater Honor

Although Peki’in is touted as a town of all four of Israel’s religions living in peaceful coexistence, today it’s primarily Druze territory — and while Margalit herself is considered an untouchable holy icon, there isn’t much tolerance for a renewed Jewish presence here. In recent years there have been attempts to reclaim a Jewish foothold in the ancient town, but harassment by the locals has consistently torpedoed those efforts.

Margalit, for her part, doesn’t focus on the gloomy predictions for the future. Every morning, as she’d done for as long as she can remember, she goes out of her little house with a broom in one hand and her walking stick in the other, and sweeps down the fallen branches and debris that have collected in the large courtyard around the ancient synagogue that is her watch, gathering up the mulberries that have fallen and washing them for the visitors that always show up later in the day.

For Margalit, there is no greater honor: for this ancient shul was originally the beis medrash of Rabi Yehoshua ben Chananyah. Rabi Yehoshua, one of the five main students of Rabi Yochanan Ben Zakai, was a Levi and served as a musician in the Beis Hamikdash. Escaping the destruction of Jerusalem along with Rabi Yochanan, he went on to serve as the av beis din in the Sanhedrin of Yavneh and later, as rosh yeshivah in Peki’in.

The structure was destroyed by an earthquake in 1837 and rebuilt about 50 years later, but one thing remained: Two large engraved stones from the destroyed Beis Hamikdash that were brought here by the fleeing Kohanim. They are still embedded in the walls of the old-new structure.

Margalit shares a famous story that she says explains her mission: Rabi Yehoshua was very brilliant, but very poor and quite homely. Yet because of his great wisdom, he was a welcome guest at the home of the Roman governor, who engaged him in intriguing discussions about the Jewish religion. Once the governor’s daughter asked him: “How is it that such beautiful wisdom should be stored in such an ugly vessel?”

Rabi Yehoshua replied, “In what kind of vessels does your father keep his wine?”

“In earthen vessels,” she answered.

“How is it fitting for a king to keep his precious wine in earthen vessels?” he asked. “Would it not be more appropriate to keep the wine in golden and silver vessels?”

And so, the princess gave orders to have the wine transferred from the earthen vessels into golden and silver ones. Very soon, the wine became sour and had to be thrown away. And then the princess understood: Wisdom is often entrusted to the person who is as humble and homely as an earthen vessel, just as wine is kept better in earthen vessels than in golden and silver ones.

For Margalit, the humble synagogue in the middle of a Druze village is where all the wisdom of her people’s legacy is stored.

Her age notwithstanding, Margalit also still supervises the hired workers attending to the family’s olive groves and zucchini fields, and she helps with the harvests. These days, she spends her mornings in a senior center in Maalot, about 20 minutes away, but is back in the afternoon to welcome and speak with the assorted visitors and tourists who make their way to the town. And no one leaves without a blessing — a long, intricate Kohanic nusach she learned from her grandfather.

Over the years, especially after her mother passed away at age 105 in 1998, Margalit has become a kind of one-woman exhibit. With her trademark headscarf, bulky sweater over a few practical layers, and orthopedic shoes, she gives the impression of a no-nonsense stalwart matron, but you can’t miss the one small nod to her femininity — lilac-colored nail polish. (“You like the color? I get a manicure every month,” she confides.)

We ask her the secret of her long life, of her strength and resilience — maybe it’s some concoction she eats, or the fresh olive oil she dips her pita into?

“I’m not so healthy,” she says in a rapid-fire, thickly Arab-accented Hebrew that’s hard to understand, especially because she has no teeth, “but one thing I can tell you — maasim tovim and ahavat chinam (good deeds and unconditional love). And make sure to say lots of Tehillim every day. If more people would say Tehillim, there wouldn’t be tzarot in the nation.”

Undetected

As we travel up the winding roads to get to this village that is itself built into the side of a mountain, we aren’t surprised that this is where people found refuge during the siege and destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans nearly 2,000 years ago. High up in the mountains of the Upper Galilee, scaling hills and cliffs and staying far from the Roman highways, three priestly families, refugees from the Jerusalem destruction, found a safe hideaway.

It’s no wonder that Rabi Shimon Bar Yochai and his son Elazar hid out here in a cave for 13 years after being condemned to death for sedition by the Romans — no Roman would find them in these parts. The cave was right next to a spring and a carob tree, both of which provided their sustenance.

To preserve their clothes, they buried themselves up to their necks in sand, saving their garments for Shabbos. They learned Torah all day and reached unfathomable spiritual heights. With the death of Emperor Hadrian, the decree against the Rashbi and Rabbi Elazar was nullified, and after 12 years they finally emerged from the cave — only to be Divinely sent back for another year in order to learn to integrate their spiritual levels with the physical world around them.

It’s the unbroken chain of Jewish life in the town that gives us precise knowledge about where Rabi Shimon’s cave is located. And as we descend the long staircase that brings us down to this sacred spot — revered by Jews and Arabs alike — we see carobs all over and a massive carob tree bent over close to the mouth of the cave. Various seismic shifts over time have changed the topography, so the cave today is more like a large crack between two rocks. The underground source of the miraculous spring has also shifted down the hill because of earthquake activity in the Galilee throughout the centuries, resurfacing several hundred meters down the steep slopes in the center of the town, its above-ground pool a landmark in the main village square.

Over the centuries, the three original Kohanic families — Tuma, Odeh, and Zinati (an acronym for “Zecher Natan Elokim Todah L’Hashem”) — were joined by others: families from other Galilean towns and nearby Lebanon, those who fled from Spain during the Inquisition, and from Ashkenazi communities as well. The kehillah absorbed many influences over the years — from the students of the Baal Shem Tov and other groups, and especially from the communities of Tzfas and Teveria. They were influences by the surrounding Arab culture as well; the Zinati family, for example, would read the Hagaddah in both Arabic and in Hebrew.

The people of Peki’in had simple, strong emunah. They recited Tehillim and learned the stories of the Chumash and Tanach, but in general, especially in modern times, they were not lamdanim or talmidei chachamim. Yet they maintained a constant dialogue and strong halachic connection with the rabbanim or Tzfas and Teveria, who answered their halachic queries, performed their marriages and other rites, mentored them, and gave them ongoing guidance.

The community of Peki’in, though, was quite isolated, and it could be days or weeks before a traveler would pass by. Although there was a certain danger, the Jews had deep emunah and bitachon, and although they were easy targets, the surrounding Arabs generally considered them untouchable.

Legend has it that hundreds of years ago, when the town was exclusively Jewish, the neighboring Arab villagers were jealous of the Jews’ never-ending water source, Rashbi’s natural spring, and one night they decided to slaughter the Jews and pillage their homes. Armed with knives and swords, they approached the town from the south, but were stopped by the spirit of Rabi Yossi of Peki’in, a Tanna who is buried there. And so, they changed tactics and decided instead to enter the town from the north, but were stopped by the spirit of Rabi Shimon Bar Yochai. Meanwhile, the Jews slept soundly, unaware of the dangers that lurked outside. The marauders, for their part, realized that the Jews had Divine protection from the holy spirits in their midst, and the town was never attacked again. Until 1938…

Don’t Waste Your Bullet

In the last centuries, while the Jews were surrounded by Druze, Christian and Muslim neighbors, most years here were peaceful. By the time Yitzchak Ben Tzvi discovered the community in the 1920s, there were still around 50 families living here, together with a Jewish school. But all that came to a crashing end in the 1930s with the Great Arab Revolt, which resulted in Jews being terrorized and murdered all over the country.

In 1938, in isolated Peki’in, terrorists from Lebanon and Syria crossed the border and the remaining Jews fled — they referred to it as galus Chadera, as that’s where they were resettled. It was the only time in history that Peki’in — the town that never went into exile since the Churban — was devoid of Jews.

In 1940, after two years in this “exile,” only one family returned: the Zinati family, direct descendants of the original priestly Zinati family who came to Peki’in so many centuries before.

Yosef Zinati, Margalit’s father, was a young man in his early thirties when he brought his family back to Peki’in. He felt it was his charge, a generations-long mission entrusted to him, to guard the ancient shul, the holy sites and the family property. His wife, a descendant of the Tuma family of Bayis Sheini Kohanim, was as strong-willed as he was and was on board as well, although when they married, it was an unlikely match — a Peki’in shidduch crisis. For years, her parents had wanted her to marry someone else, but she insisted on marrying someone from the original village Kohein line. When they married, she was already in her early thirties and he — 14 years her junior — was barely out of his teens (in the end, she outlived him by 17 years).

Yosef Zinati was a man of pure faith, and never one to capitulate or relinquish that with which he was entrusted. That faith served him well, even as he was facing a lynch mob that almost killed him. During the riots of the late 1930s, local Arabs accused him of passing information about the village to the British, and he was taken out by the mob to the town square to be killed. They didn’t want to waste a valuable bullet on the Jew, though, so they prepared a fire pit and were about to burn him alive, when at the last minute he was saved by an Arab neighbor who vouched for him. During the entire ordeal, though, he didn’t flinch. “The One who will determine whether I live or die is only Hashem,” he told his would-be executioners.

Meanwhile, the Jewish Agency/Jewish National Fund decided that for the Jews’ own safety, they would legally sell the remaining Jewish property to the Arabs and, disregarding the ancient town’s invaluable Jewish legacy, instead purchase land a bit further away. That new settlement became “Peki’in Hachadashah” — an all-Jewish town located about a mile away, which today houses a Breslov yeshivah.

Life became increasingly difficult for the Zinatis, though. There was no school for the Zinati children — Margalit and her brother, Shaul, a year her senior — so they were sent to boarding schools in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. In 1948-49, during the War of Independence, the family temporarily evacuated to Nahariya, where Shaul married and remained. Margalit, however, went back to Peki’in with her parents, and at that point decided her fate: She felt obligated to care for her parents as they aged, and she knew that if she married, she would be forced to live with her husband outside of the village. She was determined to keep a Jewish presence in Peki’in alive, even at an extreme personal cost.

No Regrets

Today there’s a small visitor’s center adjoining Margalit’s house, with clean bathrooms and cold drinking water. But there were many decades when it wasn’t like this, when there wasn’t a flow of visitors and Margalit wasn’t a celebrity. She was just a hard-working, lonely woman caring for her parents, their fields and the synagogue (her father died in 1981, and until her mother’s passing in 1998, it was just the two of them).

Still, the family wasn’t entirely off the map. In fact, every president and prime minister had visited Yosef Zinati at some point, and he had a close relationship with Yitzchak Navon, Israel’s president from 1978 to 1983. Margalit remembers how at one point, Navon had sent his own driver to Peki’in to take the Zinatis to the Kosel in Jerusalem. At that point, Yosef was blind and in a wheelchair, but Margalit watched from the women’s section as her father approached and touched the holy Wall.

Twenty-five years ago, a young actor and drama therapist by the name of Uriel Rosenbaum was on a tiyul in the area and met Margalit, who at the time was busy caring for her centenarian mother. Rosenbaum was so captivated by the Zinati family’s story that he eventually created a performance together with Margalit for groups and tourists, which evolved into the current visitor’s center that he’s been running since. Today Rosenbaum is a special education teacher and lives an hour away in Kfar Pines, but he’s been at Margalit’s nearly every day for the past two decades.

“When I first arrived, it was a different time. Margalit was quite introverted and although there was always a trickle of visitors, she didn’t really know how to communicate with them. People would take pictures with her, but they thought she was just an eccentric old woman,” he says.

Rosenbaum, though, had a mission: He got her involved with the visitors. He cleared out the old storage junk rooms attached to the house that hadn’t been touched in decades, and created a visitor’s center and museum. He staged a type of theater production the two of them would perform for visitors, and then appealed to several government organizations for help in restoring some of the property and creating a heritage site.

“The theater, the connection she developed with the public, totally changed her,” Rosenbaum says. “True, she chose her life, but it came with a level of sadness and embitterment. The theater helped her come to terms with her life and her story from a place of obligation with joy, and not from a place of an overwhelming burden. But you know, she has no regrets. She was born into a story, the story of being a symbol of endurance, and her life is a continuation of that. She’s the last Jew of Peki’in, and that’s a tremendous responsibility. ”

Did Rosenbaum in effect take a bitter woman and make her into a national symbol? “No, no,” he insists. “She was already a national symbol, but the public didn’t appreciate it, and she herself didn’t appreciate it. Yet today there is so much love between her and all her many visitors.”

Within the last year, there have been several initiatives to keep the Jewish presence alive. A group of high school girls have created a kind of learning midrashah here every Shabbos to keep Margalit company, and over the last few months there’s been a minyan in the old shul as well.

Still, Rosenbaum is realistic. He says it’s hard to imagine that there will be a continued presence here in the long run.

It’s All of Us

These days, Margalit is joined every afternoon by her nephew, Avi Zinati, a retired postal worker and the oldest son of her only brother Shaul, who passed away in 1981 when he was just 51 years old. (A month later, Yosef Zinati passed away — from illness and a broken heart.) Avi was born and still lives in Nahariya with his wife, and his six siblings and their children are the lone continuation of the Zinati-Peki’in line.

Avi Zinati is an official guardian of the Jewish holy sites together with Margalit, and since his retirement two years ago, he’s been coming from Nahariya to Peki’in every day.

Would Avi, a history buff and tour guide of the area, consider keeping the Jewish flame going here?

“I’ll be honest,” he says. “It’s not easy to live here. There are no other Jews here. And you know, my wife would never agree. So meanwhile we’ll just have to do everything we can to maintain it. To keep having guests, to maintain the shul and the house and the plots of land.

“I feel both a responsibility, and a zechut. Someone from the family is going to have to maintain and guard what’s left — so that’s us and no one else. My father, Margalit’s brother, always dreamed of coming back to the village, but it never worked out, and he died suddenly of a heart attack. So yes, I feel a responsibility to carry out the family legacy. It’s not a simple thing, but G-d Willing, Hashem will help us through this, so that the line shouldn’t be broken after 2,000 years.

“But maybe ultimately, since all of us Jews are family, we’re all responsible, we’re all the inheritors.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 906)

Oops! We could not locate your form.