Kosher Grows Up

Kosherfest founder Menachem Lubinsky reflects on the explosive rise of the kosher food industry

Photos: Jeff Zorabedian

Kosherfest, the kosher food industry’s enormous business-to-business show, has been held yearly since its launch in 1989, until now. There were many unhappy faces in kosherland when Diversified Communications, the company behind the event, announced in May that it would be discontinuing the show.

Kosherfest was a foodie’s paradise, with hundreds of booths showcasing products old and new. Anybody who was anybody attended the show: representatives from kosher companies and supermarkets, entrepreneurs launching new products, bloggers, Insta influencers, cookbook authors, politicians shaking hands. Having navigated its crowded aisles a few times myself, it struck me as resembling nothing so much as a vast beehive, designed to create an extraordinary amount of buzz.

Kosherfest began small, then grew bigger. And bigger. And then finally, the kosher world grew so big that Kosherfest collapsed under its own weight, a victim of its own success.

According to Menachem Lubinsky, the owner of Lubicom Communications and a partner in Kosherfest since its inception, the disappearance of Kosherfest is simply a result of the kosher food industry’s astronomical growth, and isn’t really bad news at all. These days, you don’t need a kosher trade show to discover exciting new products, he explains. “The emergence of enormous kosher supermarkets throughout the Jewish world means that consumers can discover new products right on the shelves of their groceries,” he elaborates. “Once upon a time, we had only small mom-and-pop groceries. There was only room for one or two brands of mayonnaise on the shelf. In today’s mega-supermarkets, there’s room for 15 brands.”

Cue the music for When Zaidy Was Young as we take a trip back to the “olden days” of the 1980s, when there were only two kinds of kosher mayo, when kosher wine meant sacramental, such as Tokay and Malaga, and when Kosherfest was nothing more than the gleam in the eye of a traveling salesman from Roslyn, Long Island.

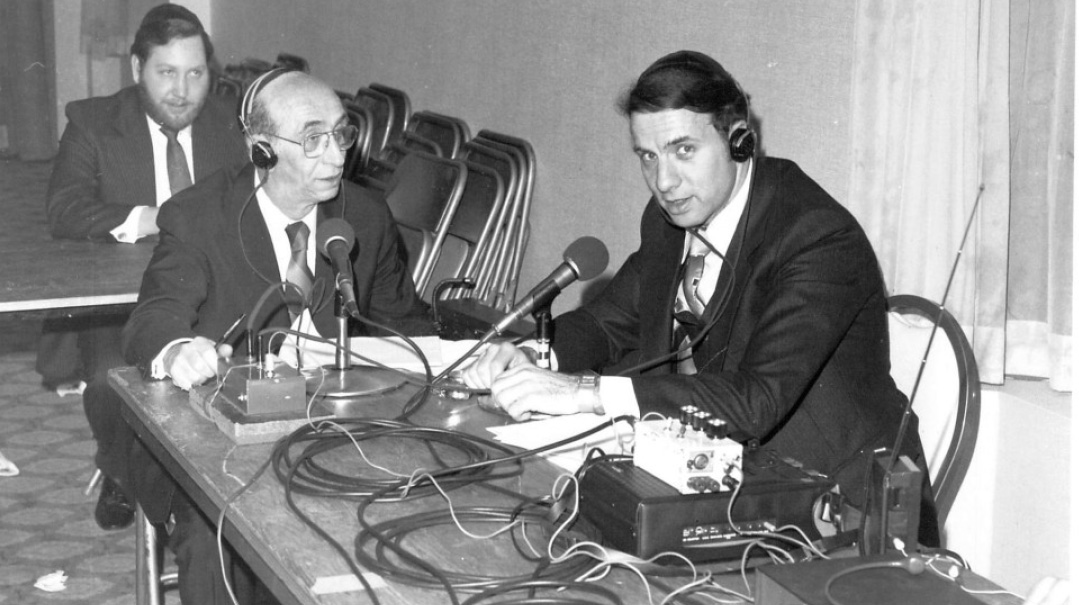

Former Vice President of Government and Public Affairs for Agudath Israel, “founding father” of Kosherfest, cochairman of the International Committee for the Preservation of Har Hazeitim are just some of the titles that Menachem Lubinsky has held over his decades of public service, leading to warm relationships with a host of leaders and decision-makers. Pictured here with Israel’s Israel’s Prime Minister Netanyahu

Not Just Gefilte Fish

Irving Silverman was a Conservative Jew who lived on Long Island and made his living selling show space for the needle trade industry, as well as from an antique store he owned in Maine. Silverman, who was accustomed to seeking out the tiny “kosher” section of supermarkets when he traveled — usually offering little more than boxes of matzoh, Manischewitz wine, and jarred gefilte fish in gelee — began noticing an increase in the range of available kosher products. Experienced with organizing shows for the needle trade, he hit on the idea of a combined kosher food trade and consumer show to help promote the nascent industry.

He gave a deposit to the Javitz Center in Manhattan, and registered the event as the Kosher Food and Jewish Life Expo. “Then he approached the OU, but it soon became clear that to partner with them he could only feature OU-certified products,” Mr. Lubinsky recounts. “Somebody over there said to him, ‘Go to Lubinsky, he’s a PR guy.’ Half an hour later he was at my door, and retained me on the spot.”

When the first show opened in March 1987, it made a big splash: The New York Times and other newspapers as well as several television stations showed up to cover it. “I davened the first minyan Motzaei Shabbos and when I arrived at the Javitz Center, there was a line snaking all the way around 34th Street with people waiting to get in,” Lubinsky says. “It was opened a few hours for the trade, including manufacturers, importers, distributors, and supermarkets, but was mostly geared toward consumers. The big kosher companies of the time — Manischewitz, Ba Tampte, Rokeach — were all represented.”

By all accounts, the event was a smashing success; so many people came that the fire marshal had to close it down for safety reasons. Everyone enjoyed the free samples — “It was like going to a big kiddush” — and Silverman repeated his success in other cities such as Chicago, Miami, and Los Angeles, although with diminishing returns that led him to discontinue the events outside the New York area.

Little Fair That Grew

Legally blind and hard of hearing, Mr. Silverman asked Lubinsky to take over the Expo. Once holding the reins, Lubinsky decided it was time to shift the Expo’s focus from a consumer-targeted event into a trade show that would give value to kosher products, putting kosher in the public eye. He collected as much data as he could about the kosher food industry — not an easy task at the time, as companies then held data close to their chests — and geared up to revamp and rebrand. He booked a space at the Giants Club, at the old Giants Stadium in Rutherford, New Jersey, and in 1989, Kosherfest was born as a business-to-business kosher trade show.

The event featured 69 exhibitors and 100 booths, and was attended by 700 people, mostly from the trade. “This was 1989,” Mr. Lubinsky reminds us. “It was before the internet and cell phones, and there wasn’t a single large kosher supermarket back then.” Lubinsky created a trade newsletter entitled Kosher Today and gave scores of media interviews.

Just a year later, the space at Giants Stadium was already too small, and Kosherfest moved to occupy half the Meadowlands convention center. It then moved back to the Javits Center for a few years, then returned to the Meadowlands. At its peak in 2018 it boasted 330 exhibitors, 400 booths, and over 6,000 visitors from 35 countries.

By 2003, after producing Kosherfest for 13 years, Lubinsky was ready to hand it over to a large company that would assume its management. His search led him to Diversified Communications in Portland, Maine, a company that produces large trade shows. While it wasn’t a Jewish company, they had produced other ethnic food shows such as Comida Latina and the All Asia show.

When Diversified signed on, they included an agreement with Lubinsky to retain him as a consulting agent for one year. “They renewed that agreement 19 times,” Mr. Lubinsky says with a smile. “I had become the face of the show, and I remained the face of the show.”

The show ran every year in November, so scheduled because it’s generally the last month in which stores place their Pesach orders. “Pesach is 40–50 percent of all kosher marketing,” Mr. Lubinsky says. “Even non-religious Jews buy a lot of kosher products for Pesach — the Manischewitz brand alone sells in over 18,000 stores across the country.”

As a young Agudah employee, speaking on the radio

Infant to Ravenous Adolescent

Kosherfest flourished as the kosher market grew by leaps and bounds. By 2008 the first large-scale kosher supermarket, Pomegranate, had opened, followed by others. Today, Mr. Lubinsky says, there are 62 kosher supermarkets in existence that are at least 10,000 square feet in size, with another seven under construction. “When the large kosher supermarkets opened, they had the room to showcase all the new products on the market,” he says. “They launched the golden era of the kosher consumer.”

One-stop-shopping boosted the popularity of big stores: While a balabusta once needed to shop at multiple stores — the fish store, the fruit store, the butcher, the grocery — now she could go to one place and find everything she needed.

In 1987, when Lubinsky first took inventory, there were about 6,000 kosher products on the market. From 2005–2015, 5,000 new products were added every year. Kosher is now the number one category in new products, and today there are at least 300,000 kosher-certified products, plus a long list of kosher ingredients.

Rabbi Moshe Elefant, COO of the Orthodox Union, believes that Menachem Lubinsky’s influence in this space “cannot be overstated… For him it became a mission to help kosher grow.

“Most of the companies the OU certifies aren’t Jewish, and when we meet them, it’s the first time ever they’ve spoken to a rabbi,” he continues. “But Menachem Lubinsky comes with us, and he’s clean-shaven, articulate, professional, and not affiliated with any kashrus organization. He’s compiled all the statistics to show them how becoming kosher will help them, statistics I find very important when I do my own presentations.”

Numerous studies have shown that kosher certification adds value to a product even for non-kosher consumers, in the same way that labels like “organic” or “no artificial flavors or colors” do; they believe kosher products to be more clean or healthy. Producers who try out certification generally never rescind it, recognizing that certification boosts sales. Many specialty markets — catering to halal consumers who buy kosher meat, or vegans who want only pareve-certified products — have also become devoted kosher consumers.

Kosher may also enjoy a certain crossover cachet in out-of-town stores; at Jewel-Osco in Evanston, Illinois, a manager overheard customers exclaiming, “Hey, they’ve got New York-style knishes here!”

In those smaller communities, non-Jewish supermarket owners have learned that it behooves them to keep kosher items well-stocked. Mr. Lubinsky cites the case of a supermarket in Kansas City: When it began stocking kosher products for the 100 interested families in the area, those families became loyal customers who returned faithfully each week. The return on kosher investment was well beyond what they’d expected.

As the years passed, global factors abetted the explosion of kosher products. The trend of moving production to China hasn’t skipped the kosher food industry, so that today there are 3,000 kosher-certified products manufactured in China and the Far East. Rabbi Elefant acknowledges the mesirus nefesh of the many mashgichim who spend weeks away from their families in remote places like Singapore, South Korea, and China.

He also gratefully notes that the growth of Chabad has been of immense help to the OU, in an arrangement that benefits both sides. “The Chabad shluchim who go to faraway places work for us as mashgichim as well,” he says. “This provides the OU with local mashgichim, which saves us from needing to fly people out from the US. The shluchim have become part of our army, and they benefit not only from the extra income but from giving supervision to local products they themselves can consume as well.”

“It’s a great miracle that the kashrus companies not only kept up with the growth, but raised their standards,” Mr. Lubinsky points out. “They are truly the unsung heroes of the story. The formation of the AKO [Assocation of Kosher Organizations, headed by CRC director Rav Sholem Fishbane] has done a tremendous amount to set standards and coordinate kashrus supervision.”

The Israeli food industry has also seen exponential growth that Lubinsky is proud to have been a part of. “They’re light years ahead of us in technology and food chemistry,” he says. “They can take an ingredient and chemically split it to take out the lactose or sucrose.” The frequency with which kosher consumers travel to and from Eretz Yisrael created more demand for Israeli products, so that Bamba, Elite chocolates, frozen soy-based meat substitutes, and many other products have become standard in kosher stores.

Next-Level Kosher

As the American food market became increasingly sophisticated, the kosher market followed. Trends in the non-kosher world — sushi, gluten-free, sourdough, organic foods — were picked up by kosher producers. In the late 1980s and onwards, notes a leading source from kosher retail, the large numbers of baalei teshuvah who entered the community also drove demand for new products. Coming into the frum world acquainted with a broad range of international foods, they would often ask him to obtain the products they’d once enjoyed in a kosher version.

The growth of frum magazines (Mishpacha’s English edition debuted in 2004) also raised standards for the kosher industry, as the need to produce a weekly stream of appealing kosher recipes and feature new products from advertisers drove an explosion of culinary creativity. The number of kosher cookbooks was about 11 when Kosherfest launched; today there are over 150.

The Kedem company opened the world to fine kosher wines, starting the Kosher Food and Wine Expo that draws 50,000 people yearly in multiple venues. “Restaurants come to showcase their food, but people really come for the wine,” Mr. Lubinsky notes.

Once satisfied with brisket and kugel, we Jews have become a nation of feinschmeckers. “Today’s kosher consumer is discerning,” Mr. Lubinsky says. “He appreciates and is willing to pay for quality. The new generation is fueling the restaurant business, but the home cook has also turned into a chef. People not only want to produce fine food but to present it attractively.”

When he first started, he recalls, people were dismissive of kosher food as somehow less tasty, but no one can make such a claim today. When he attends the Fancy Food show, he says, less-observant Jews often approach him to say, “I’m not kosher now, but I’m really going to do it.”

“Today it’s no longer, ‘Why keep kosher?’ ” he says. “It’s ‘Why not?’

“You don’t give up eating well. Today you have kosher in the White House, you have a Hyatt Hotel in the Bahamas with a kosher restaurant.”

Victim of Its Own Success

Like most businesses, Kosherfest took a hiatus during the pandemic, but by the time it came back in 2021 it was beginning to show signs of wear. “It wasn’t a chiddush any longer,” Mr. Lubinsky says. “It was becoming the same people, the same products every year. Now that the kosher food industry had expanded from a 200-million-dollar business to an estimated three-billion-dollar business, we no longer needed Kosherfest to expose kosher food. It was time to look for the next level.”

Another factor contributing to Kosherfest’s decline, Rabbi Elefant says, is that suppliers realized their bottom lines hadn’t suffered during the Covid hiatus. “If anything, their sales continued to increase,” he says.

Some vendors left Kosherfest because they weren’t successful; others left because they were. Mr. Lubinsky recalls his surprise when, halfway through the first day of one Kosherfest, he saw an Israeli vendor who sold colored pasta packing up his booth. “Why are you leaving? You’ll leave a gap in the show,” Lubinsky said. The man answered, “I don’t need to be here anymore. I found a distributor for my product. I’m done!”

Today, so many products boast kosher certification that the kosher market has penetrated the non-kosher market, which effectively eliminates the need for a separate grocery aisle. “What even qualifies as a kosher niche market today?” Rabbi Elefant asks rhetorically. “Jarred gefilte fish? The kosher products are mainstream, they don’t need their own aisle. Would you put Cheerios in the kosher aisle because they have an OU?”

Between the kosher bloggers, magazine writers, and Instagram influencers, and the kosher mega-supermarkets, there’s no longer a need for Kosherfest to introduce new products, leading up to Diversified Communications’ regretful announcement that they have decided to discontinue Kosherfest. It was a victim of its own success: It made kosher food so ubiquitous and popular that it has gone mainstream and doesn’t need its own special trade show. “All it means is that the industry has matured,” Rabbi Elefant says. “But what Kosherfest accomplished will never go away.”

Nor does it signal the end of all kosher food shows. Just this past June, there were two kosher food expos, JFood by Compass Conferences in Edison, New Jersey for businesses and consumers, and Kosherpalooza, produced by Fleishigs Magazine and Powwow Events, that were well attended and hope to continue in the future.

“The end of Kosherfest simply means that kosher industry has grown up,” Mr. Lubinsky says. “You raise your babies, and when you do it well, they grow up and move on. You wouldn’t want it any other way.”

The Man Behind It All

Now a great-grandfather, Menachem Lubinsky possesses a gracious combination of intelligence and menschlichkeit. His warm, unassuming, yet self-assured presence inspires a trust that surely contributed to his success in the business world and community affairs.

His parents, both Polish Jews who had gone through “the worst concentration camps,” met and married after the war. His father became the chief rabbi in Hanover, Germany from 1945–50, and spent much of his time helping fellow survivors get back on their feet and figure out their next step in life. (Lubinsky is in the process of drafting a book about his father’s life, based on his voluminous correspondence.)

“When people think of the war, they think of the camps,” he says. “But they aren’t aware of the difficult realities the survivors had to deal with afterward. Where should they go — to Palestine, which was another war zone, or America or Australia? Where did they have family who could take them in?”

The Lubinsky family arrived in New York when Menachem was nine months old, settling in Crown Heights. He attended the Bobov elementary school, and was the only one of the 27 boys in his classroom who had a grandparent. “I thought Jewish people simply didn’t have grandparents,” he says.

He has memories of seeing the Lubavitcher Rebbe walking down Brooklyn Avenue every day and waving to him, often observed by the Rebbetzin driving alongside. Then the Lubinskys moved to Boro Park, where he attended Yeshiva Torah Vodaath, followed by a period learning in Eretz Yisrael at the Chevron Yeshiva. He received semichah there (and developed an excellent command of Ivrit, which he says has helped enormously when dealing with the Israeli food industry).

After leaving yeshivah, he earned a BA and MBA in marketing and advertising at Baruch College. He married Hindy (Fink), who currently serves as chair of the Touro Graduate School of Speech and Language, and they were blessed with three daughters. He served as the founding director of the Boro Park Senior Citizens Center and Project COPE (Career Opportunities Preparation for Employment), before leaving to take a job at Agudath Israel working for Rabbi Moshe Sherer z”l.

“He was my mentor in everything,” he says with obvious gratitude and admiration. “He taught not just by words but by example — even down to how to put a staple in a document (crooked, so that it’s easy for the reader to open).”

Rabbi Sherer appointed Lubinsky to be his public relations representative in Washington, D.C. “I took that on very reluctantly,” he says, “but Rabbi Sherer told me, ‘I’m giving you one of the loves of my life,’ and I had no choice but to give it my best.”

In his capacity as Vice President of Government and Public Affairs of Agudath Israel of America, Lubinsky represented 600 Jewish elementary, high school, and postgraduate schools, and shuttled between Washington, Albany, and City Hall.

His years of service in Washington led him to meet every American president from Reagan to Biden (whom he met when Biden was a senator). Their signed photos, and those of Mayors Dinkins and Bloomberg, along with (l’havdil) photos of Rav Steinman and Rav Elyashiv, are the sum and total of the wall decoration of his comfortable but modest office.

President Reagan was proud to tell him that he could pronounce his name, Menachem, as he’d had experience from his meetings with Menachem Begin. President Obama, upon hearing that he was an authority on the food industry, told him that his wife Michelle was very interested in food and was writing a book about it.

The office also boasts a life-sized photographic cardboard cutout of Lubinsky, which was created as a joke when it became clear that he couldn’t possibly pose for pictures with every single person at Kosherfest who wanted one. “There was one day when 400 people took pictures with my cutout,” he says with a smile.

Mr. Lubinsky left the Agudah in 1984 to open Lubicom, his own public relations firm. He took on various advertising clients, many of them kosher food companies. Three years later, he opened his office door to receive the fateful visit from Mr. Irving Silverman.

While he’s best known for Kosherfest and public relations, Mr. Lubinsky never abandoned the passion for community service that marked the early years of his career, and has had a long and distinguished history. He served as president and chairman of the board of the Metropolitan NY Coordinating Council on Jewish Poverty for more than 30 years, and vice president of Agudath Israel of America. COJO, UJA, and Chai Lifeline are just a few more of the organizations he has served and advised. Together with his brother Avrohom and friend and neighbor Malcolm Hoenlein, he also serves as the cochairman of the International Committee for the Preservation of Har Hazeitim, where his parents are buried.

With so many years of involvement in kosher food, I couldn’t resist asking what he himself likes to eat. He smiles. “I like most things, but I prefer lean food,” he says. “Nothing too salty, sweet, or spicy.” When he visits Eretz Yisrael, however, he admits that his favorite haunt is Hadar Geula — good, hot, filling Jewish food

The Lure of Kosher

Kosher supermarkets today are light years away from corner groceries of years ago. Mr. Lubinsky’s office is just a few blocks from the Gourmet Glatt supermarket in Boro Park, and we walk over for a short tour, as I listen to his insights into the way the kosher grocery business has evolved.

Selling food is all about product placement and the shopping experience, he says. “Experts advise that a supermarket lead with the senses, starting with sight,” he explains. “They put the fruit and vegetable section up front, so that your eyes are filled with colors. After that there’s usually the bakery and the takeout, which stimulate the sense of smell and entice people to buy. Takeout offers a high profit margin for stores, and so do frozen prepared foods.”

Sure enough, the first section we pass through is for fruits and vegetables, with a bakery section and takeout counter just beyond. Mr. Lubinsky points out a refrigerated section of “to-go” foods — packaged sandwiches and salads a consumer can pick up for a quick lunch or snack. “This is a category unto itself today,” he says. Similarly, frozen convenience foods (think chicken nuggets, French fries, pizza) have become staples for kosher families; more women work nowadays and rely on shortcuts to feed their families.

Next he indicates the fish counter, dedicated to Ossie’s fish products. “This is another new innovation — to bring in independent brands,” he says. “Instead of competing with outside vendors, the supermarkets bring them into the store and take a percentage. It’s win-win for everyone.”

The snack aisle overflows with a dizzying array of colorful snack bags. “There never used to be heimish snack aisles,” Mr. Lubinsky points out. “But today it’s a major category. In fact, Lays potato chips ended up pursuing an OU-P certification just to stay competitive in the kosher market.”

Kosher supermarkets see their greatest foot traffic between Wednesday and Friday, as shoppers stock up for Shabbos. Working people sometimes shop on Sundays to set up their week. The downside is that Mondays and Tuesdays tend to be slow days. How do you bring in the crowds when there’s no pressure to buy? “Many places started scheduling events like food demos on those days,” Mr. Lubinsky says. “It gives people a reason to come out and allows new products to be introduced.” Following the lead of stores like Whole Foods and Wegmans, the stores turn the humdrum task of food shopping into a new form of entertainment.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 968)

Oops! We could not locate your form.