Joint Venture

Hidden in the archives of the “Joint” is the little-known account of the massive relief effort launched to rescue and rebuild the remnants of Torah Jewry

Photos: Pinchas Emanuel, JDC Archives

WESTERN UNION CABLEGRAM

August 31, 1914

Jacob Schiff

New York

Palestinian Jews facing terrible crisis. Belligerent countries stopping their assistance. … Fifty thousand dollars needed. … Conditions certainly justify American help. Will you undertake matter?

Morgenthau

When World War I broke out in early August of 1914, Henry Morgenthau, Sr., was the US ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, one of the few Jews serving at the highest levels of the American government. From his “front-row seat,” he saw a disaster unfolding before his eyes. The Jews of Eretz Yisrael’s Old Yishuv had always lived a precarious existence. Although their needs were few, they depended upon contributions from abroad to buy what little they did need — food, medicine, and other basic provisions.

“Abroad” in those days meant, for the most part, the Jewish communities of Europe. But when war broke out on the Continent, the borders closed. Just as people could no longer freely pass from one country to another, neither could money. Overnight, the tzedakah pipeline was shut down.

The result, in Ambassador Morgenthau’s words, was a “terrible crisis.” And that was after just one month of war.

Although American Jewry hadn’t forgotten their less fortunate brethren, it now became clear they would have to shoulder a larger burden. To some it also became clear that the old way of communal giving — a plethora of small organizations, each giving to its own — wouldn’t be effective during wartime, when the usual channels of transferring money were blocked, and new ones had to be found. What was needed was something new, something bold, something seemingly impossible. In two words, what was needed was Jewish unity.

Would American Jews set aside their religious and political differences to help?

We have to work together. That was the call of the day.

On a September day 105 years after Henry Morgenthau sent off his now-famous cablegram, I’m sitting in the Jerusalem Archives of Joint Distribution Committee with historian Ori Kraushar. On his desk is a photograph taken in 1918 that captures a meeting in the office of American banker and philanthropist Felix Warburg. Among the more than two dozen people seated around a long table — a group that includes Orthodox rabbis, socialist firebrands, and a few millionaire capitalists — is Jacob Schiff, the recipient of Morgenthau’s cablegram. Not only did Schiff, one of the wealthiest and most influential American Jews of the time, succeed in raising the $50,000 in lightning speed — over $1,200,000 in today’s money — the fundraising campaign resulted in the establishment of one of America’s largest and most effective Jewish relief organizations: the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, commonly known as JDC, or the Joint.

“The Joint was formed from three organizations, representing three diverse segments of American Jewry,” Ori explains. “They said, ‘We have to unite and work together. All Am Yisrael are brothers.’ ”

The three organizations were the American Jewish Relief Committee, established by the American Jewish Committee and favored by wealthy businessmen — many of whom were Reform Jews who had immigrated to the US from Germany, such as Jacob Schiff; the Central Committee for the Relief of Jews, established by the Union of Orthodox Congregations of America (today’s OU); and the labor-socialist Jewish People’s Relief Committee.

Fine words about the need for unity were nice. But how was it possible, in reality, for Jews with such different worldviews to sit at the same table?

The fact that Warburg, Schiff, and other members of the American Jewish Committee were acting as individuals, and not as representatives of Reform institutions, enabled the OU’s Albert Lucas, for example, to serve as secretary of the Joint. In contrast, Lucas refused to join forces with Reform clergymen at other organizations, even when he believed in the cause.

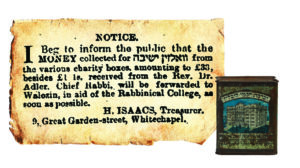

While the impetus for establishing the Joint was the dire situation in Ottoman-ruled Eretz Yisrael, the war in Europe soon created devastation in Europe’s Jewish communities too. Appeals for donations to help “Jewish War Sufferers” became part of an American Jew’s daily life. There were Yom Kippur appeals, Pesach appeals, and charity bazaars. Money was even raised at chasunahs. Each organization continued to target its own group of supporters for contributions, but they agreed to give the money to the Joint for distribution, which promised to allocate the money in an equitable fashion. Because the Joint had the support of wealthy bankers and businessmen such as Schiff and Warburg, prominent lawyer Louis Marshall, and other influential members of the Jewish community, they could parley their influence into assistance from the US government for the transfer of money and desperately needed food supplies even after America entered the war in 1917.

After the war ended in 1918, it was assumed that the world would return to normal, the Joint would break up, and the organizations would go their separate ways. But the rise to power of the communist regime in Russia and Hitler, yimach shemo, in Germany, the Holocaust that followed, and the refugee crisis of the post-war years meant that, if anything, as the century progressed, the need for a united relief effort had become even more urgent.

The story of the Joint’s work to help fund soup kitchens, orphanages, schools, medical clinics, and old age homes serving war-ravaged communities is well known. But there is a lesser-known chapter in the Joint’s history worth remembering too: the support the Joint gave to the Torah world both in Europe and Eretz Yisrael, whether it was to yeshivos and their near-starving bochurim, broken-hearted agunos, or European rabbanim left penniless and bereft of their kehillos after the Holocaust.

It is this story that I’ve come to hear and Ori, an enthusiastic storyteller, gives me a glimpse into a few of the treasures hidden away in JDC Israel’s archives. For a few hours we put our computers and cellphones aside and turn our attention to typewritten letters written on fragile, super-thin paper, mimeographed reports with their faded purple ink, black-and-white photos where smiles of hope can be seen amidst the destruction and despair.

“The Joint’s purpose was never to change or impose an agenda on the people who received its aid,” Ori clarifies. “It always wants to learn what a kehillah needs. What’s needed in Poland might not be right for Lita, which might not be right for Eretz Yisrael.” Adding that the Joint is still very active in Israel, among other parts of the world, he comments, “We’re there to help.”

Help was certainly needed for the Jews living in communist Russia.

January 28, 1930

To the Leaders of Israel, Members of the Joint Distribution Committee

Greetings: The terrifying news about our unfortunate brethren in Russia are unequaled in the history of the Jews. Hordes of savages and wild beasts thrust themselves on Israel and his religion …and about three million Jews are being robbed and persecuted… all because they cling to the Jewish beliefs and religion. The human pen cannot describe how bad and how bitter is the plight of those who fear the word of God… LET NOT THE EARTH COVER THEIR BLOOD!

The letter continues with a fervent plea for assistance — at least $300,000 is the requested amount. That’s about $4,400,000 in today’s money. But what’s most interesting about the letter are the signatures found at the end: the Chofetz Chaim, the Gerrer Rebbe, the Alexander Rebbe, Rabbi Shlomo David Kahane, president of the Warsaw Rabbinate, and Rabbi Yechezkel Lifshitz, president of the Agudath HaRabbanim of Poland. A previous appeal by Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, the Rebbe Rayatz of Lubavitch, is mentioned in the letter as well, making it a truly joint effort of the leading rabbanim of the time.

The Joint wasn’t exactly a stranger to the situation in Russia. After World War I, in conjunction with the American Relief Administration, it sent convoys of trucks loaded with food, medicine, and clothing to impoverished Jewish communities. The JDC-created Russian Matzah Fund Committee helped to ensure that major cities, at least, had matzos for Pesach. It also worked closely with the Russian OZE Committee, an organization dedicated to the promotion of health, hygiene, and childcare, among other activities. So why this urgent plea now? What had changed to turn the situation in Russia from awful to terrifying?

The year 1929 was a disastrous one for Russia’s Torah-observant Jews. In April of that year, a law was put into effect that gave the state absolute control over the country’s religious institutions and religious leaders. The culmination of a decade-long program to wipe out Torah observance on Russian soil, the new edict meant that rabbanim and Torah-observant communal leaders were forbidden to conduct any financial, educational, or charitable activities.

Of course, yeshivos and chadarim had already been operating underground for many years; many survived thanks to financial support from the Joint. But the new law imposed even harsher punishments on any rav caught committing the crime of teaching Torah. Distributing funds from organizations such as the Joint also became a crime.

But 1929 was disastrous for another reason as well. On October 24, 1929, Wall Street crashed. People who the day before were millionaires on paper woke up to discover they were now practically penniless. Businesses and factories closed, turning the working poor into just poor. With so many American Jews needing assistance, some philanthropic organizations reduced their contributions to communities in Europe and Eretz Yisrael.

The letter from the Chofetz Chaim, the Gerrer Rebbe, and the others therefore wasn’t an exaggeration. Those were indeed terrifying times.

In our era of WhatsApp and Instagram, it’s sometimes hard to remember that there was once a time when people couldn’t know what was happening on the other side of the world in real time. Felix Warburg could therefore perhaps be forgiven for being puzzled when the Joint received a frantic letter from someone named D. R. Travis from Tulsa, Oklahoma, concerning the desperate situation of the yeshivos in Eretz Yisrael. He therefore wrote to Judah L. Magnes, a Reform clergyman and member of the Joint, who was then in Eretz Yisrael:

May 29, 1937

Magnes

Jerusalem

Travis of Oklahoma just back from Palestine. Reports yeshiva conditions bad. Pople [sic] starving. Stop. Have misgivings correctness his statements. … Would like information …

Warburg

The letter is puzzling. The Joint had been working in Eretz Yisrael since 1914. Why didn’t Warburg know about the condition of the yeshivos? Was it Travis who was misinformed?

The misunderstanding, says Ori, was due to a few factors. For one thing, the economic situation in Eretz Yisrael, which had been disastrous during the World War I years, had improved during the 1920s and 1930s. But during the same period, the situation in Europe had gone from bad to worse, claiming more of the Jewish world’s money and attention.

“During the 1930’s, several yeshivos left Europe,” Ori explains. “The United States was mainly closed to Jewish immigration, so the yeshivos went to Eretz Yisrael. While the Joint’s budget for yeshivos might have been enough to support ten of them, it wasn’t enough to support twenty.”

Warburg asked an investigative team already in Eretz Yisrael to find out the true situation. Their findings? Mr. Travis was right. The situation of the yeshivos was terrible.

That conclusion was confirmed by Rabbi Yitzhak Halevi Herzog, who had become the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Eretz Yisrael in 1936. On September 17, 1939, he penned a letter to the Joint, in which he wrote:

You can hardly form an idea of the actual position. … The revenue from abroad has all of a sudden stopped and the institutions as such as well as the large numbers of Fellows, scholars and students dependent upon them are literally on the verge of starvation. For G-d’s sake cable a few thousand pounds for the saving of the Torah in the whole of Eretz Yisrael.

The reason, of course, for why revenue from abroad had stopped “all of a sudden” was the outbreak of World War II on September 1, 1939. Once again, borders closed.

The irony, comments Ori, is that by the time the Joint fully understood the extent of the problem in Eretz Yisrael and agreed to increase its support for the yeshivos, the new war in Europe changed everything. Faced with limited financial resources, rescuing Jews trapped in Nazi-occupied Europe became the Joint’s number one priority.

No one would have argued about the importance of rescuing Europe’s Jews. But Rabbi Herzog saw clearly what many others didn’t yet see. The days when Europe was the center of Torah learning were over. If something wasn’t done to save the yeshivos in Eretz Yisrael from collapse, “the last burning light of Torah” would be extinguished from the world.

On May 7, 1941, during a visit to New York, Rabbi Herzog sent the Joint another letter. A previous request for additional funding for yeshivos had been denied. But Rabbi Herzog refused to take no for an answer. He stated his demands: $120,000 to transport 300 yeshivah students from Europe to Eretz Yisrael and maintain them for at least a year; double the Joint’s monthly allocation for supporting Eretz Yisrael’s yeshivos; and raise the monthly allowance allocated to helping rabbanim forced to leave Europe, who were now living in Eretz Yisrael.

Rabbi Herzog concludes his letter by writing:

I would feel sad in the extreme, if I would have to tell my people on my return to the Holy Land, P. G. [Please G-d], that the spiritual head of Palestine Jewry had pleaded in person for the first time in the history of American Jewry before the J.D.C., and that his requests on behalf of the Torah were simply “turned down”.

I refuse to believe that this will be the message that I will have to bring back to Zion!

Fortunately, it wasn’t. This time, says Ori, the Joint responded: “We’ll find a way to help.”

One of the terrible strikes of the war is the ruined family life.

In a November 1940 letter to the Joint from the office of Rabbi Shlomo David Kahane, the plight of women left agunos by the war is discussed. During World War I, Rabbi Kahane, then head of the Warsaw Beis Din, had worked tirelessly to free some 50,000 women who had been left in limbo — yet another casualty of war.

… we were able to get enough information about the Fate of a large number of men, and release the women from everlasting abandonment.

When war in Europe broke out a second time, it was only natural for the women to turn to Rabbi Kahane for help. By 1940, though, Rabbi Kahane was the chief rabbi of Jerusalem’s Old City. But despite the distance and the difficulty of establishing lines of communication, Rabbi Kahane took on the task.

“He sent people to interview survivors in Europe and people who had made it to Eretz Yisrael, to question them about their families,” Ori explains. “From this information, he was able to build profiles and help the agunos. The Joint helped Rav Kahane both with money and with gathering the needed information.”

Another casualty of war was seforim.

“Most of the seforim were destroyed by the Germans,” says Ori, “which made it difficult for rabbanim who had survived the war to pasken — they didn’t have seforim to refer to. So the Joint sent seforim.”

The Joint also helped fund the historic Survivors’ Talmud. With hundreds of thousands of survivors still languishing in DP camps after the war, a group of rabbis approached the US Army with a request: Print 3,000 full-sized copies of the Talmud as a gesture symbolizing the survival of the Jewish people despite attempts to annihilate us.

The army agreed to supervise the production of the Talmud, along with the Joint — no easy task considering the post-war shortages of paper and ink. And, of course, finding a complete set of the Talmud to use as a prototype was a seemingly impossible task too. Even in the United States, a complete set was hard to find, because American Jews had relied on the printing presses of Europe, which had all been destroyed.

In the end, two complete sets were found in New York. But by this time, the US Army was balking at the scope of the project. The print run was therefore reduced to just 50 complete sets, with the Joint and the German government shouldering the costs. The Joint managed to print a few additional sets, and today they are a collector’s item.

After the Second World War, funding social and educational projects in Eretz Yisrael became one of the Joint’s top priorities.

Among the many survivors who were trying to rebuild their lives were rabbanim who had formerly held respected posts back in Europe. “In Eretz Yisrael they no longer had a kehillah, they no longer had a salary,” explains Ori. “It was difficult for someone who had always earned his living to now accept charity.”

It was Rabbi Meir Bar Ilan, with the support of Rav Herzog, who came up with an idea for how to give these rabbanim kavod and money to live. He suggested the establishment of two projects. The first was the Encyclopedia Talmudit, a summary, in alphabetical order, of halachic topics found in the Talmud. The second was Otzar HaPoskim, a collection of halachah and responsa literature organized according to the order of the Shulchan Aruch.

The Joint agreed to partially fund the two projects but, Ori comments, there was never enough money for all the challenges facing the postwar community. Still, the Joint responded as well as it could. Money from the Joint helped to construct the building of several yeshivos, including Kol Torah in Bayit Vegan and Ponevezh in Bnei Brak.

In 1955, the Joint opened a department in Eretz Yisrael that dealt exclusively with the challenges facing the yeshivah world — including the physical ones.

“There was a great need for this,” says Ori. “Yeshivah students didn’t eat well. Their health was awful. They weren’t always members of kupat cholim, so when they got sick, they wouldn’t get treatment there. The Joint therefore brought in a professional nutritionist to help improve the diet of the bochurim and established a clinic for bnei yeshivos so they could have access to doctors and dentists.”

These few examples of assistance are really just the tip of the iceberg, says Ori, who proceeds to give me a tour of the archive.

Many of the documents recording the Joint’s postwar work with the yeshivos in Eretz Yisrael are stored in archival-quality boxes at JDC’s Jerusalem office in Givat Ram, which is where Ori and I have been talking. There is also an archive in Givat Shaul, Ori explains, as well as the JDC Archives in New York, which contains material dating back to the Joint’s establishment in 1914.

The JDC Archives in New York began to digitalize its collection of text documents, photos, and artifacts about a decade ago, and the work continues. According to Ori, there are millions of items in the archives and more than 500 boxes of material are still waiting to be scanned. That includes more than 50 boxes — some 800 documents — pertaining to the yeshivos the Joint helped support. The goal is to make the material more easily accessible for scholars, as well as individuals who might want to research their family history.

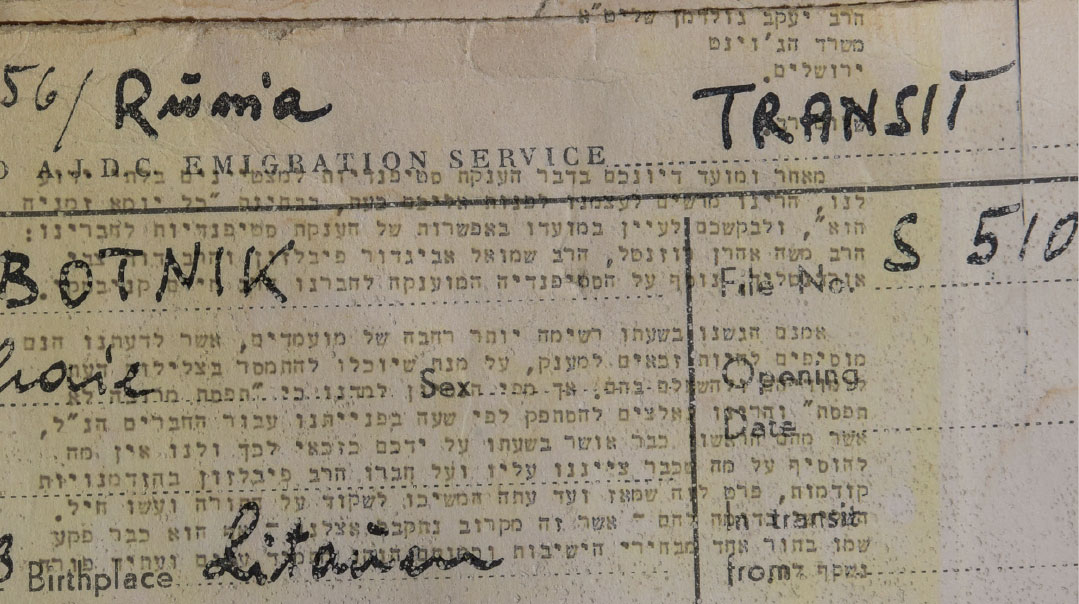

For instance, the archive has boxes and boxes of index cards detailing information about people the Joint helped rescue during and after World War II — including the card for Rav Aharon Yehuda Leib Steinman and his wife, who were brought from Switzerland to Eretz Yisrael, thanks to a loan from the Joint.

“The Joint’s history tells the story of Am Yisrael during the past 100 years,” Ori comments. “The Joint has done a lot, but they don’t publicize it. Some of what’s stored in the archive is material that hasn’t seen the light of day for decades. It’s never been published. Now, we’d like to share this story with the public.” —

The Second 100 Years

The end of World War II didn’t mean there was no longer a need for a relief organization such as the Joint. Eastern Europe’s Jews continued to require assistance, both during the communist years and after the fall of the former USSR. The collapse of Argentina’s economy and, later, that of Venezuela, demanded a call to action for those communities too. Helping Ethiopian and Iranian Jews… the list goes on and on.

But according to Ruben Gorbatt, the JDC’s director of programs for chareidim, and Yitzchak Trachtengott, manager of chareidi programs, the Joint has also continued its work of helping to support Israel’s chareidi community.

“Aid to yeshivos is designed to help the community according to its needs,” says Mr. Gorbatt. “Just as in the past the Joint worked with rabbanim and heads of kehillos to help out with whatever was necessary, in accordance with the values and principles of the community, the Joint still assists the chareidi community in various needs, in full cooperation and partnership with the rabbanim and roshei yeshivos.”

Harav Yitzchak Trachtengott adds, “We’re currently running several programs and initiatives in yeshivos, with the full approval of gedolai Yisrael, in order to promote the best future for the boys. The Joint sees it as a big zechus.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 781)

Oops! We could not locate your form.