Joint Forces

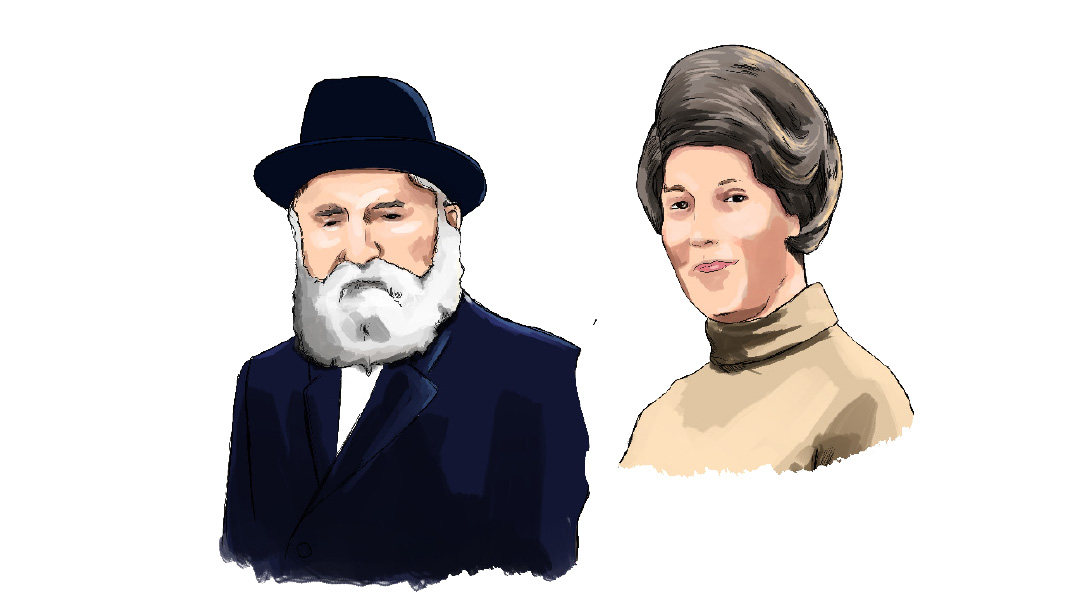

How gedolim built marriages infused with loyalty, purpose, deep respect, and affection

A look at the relationships of some of our greatest couples — unions with different dynamics, different breakdown of roles, different flavors — but with deep respect and affection we can all learn from

The Most Privileged

Rav Moshe and Rebbetzin Sima Feinstein

Rebbetzin Sima, wife of American Jewry’s ultimate posek, Rav Moshe Feinstein, demonstrated utmost respect for her husband. Family members recount that not only was the respect mutual, it was accompanied by deep gratitude and genuine affection

IT

was 1922, time for Sima Kustanovich, the “princess” of her town of Luban, Belarus, to get married. Shadchanim suggested the cream of the crop, the top boys in the area. The name Moshe Feinstein, the young rav of Luban, was the most illustrious one, but she just had one issue with the idea: “He’s a head shorter than me,” she said doubtfully to her father, Rav Yaakov Moshe, who was rosh hakahal of the town.

He reassured her she needn’t meet the short illui. “It’s fine,” he said. “Don’t meet with him. But just know, I will die if you don’t.”

She met him.

And the short man, with his loyal wife at his side, very soon became greater than them all.

During their engagement, the young couple went to seek a brachah from Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, one of Rav Moshe’s rebbeim and the rav of the nearby town of Slutzk.

“All the townspeople came to their doorsteps to stare at me,” Rebbetzin Sima would later recount. “They all wanted to see the fortunate young woman who would marry their rav’s beloved talmid. I felt like visiting royalty.”

Throughout the ensuing 65 years of their marriage, that feeling never left her.

They married that same year, settled in Luban, and brought four children into the world. Pesach Chaim, the eldest, was niftar at three years old from whooping cough. That left Fia Gittel, Shifra, and Dovid. Later, after immigrating to the United States, they were blessed with their youngest, Shalom Reuven.

If you wanted to characterize the tenor of their relationship in a single phrase, it would be “hakaras hatov.” Reb Moshe and Rebbetzin Sima recognized not only each other’s obvious kochos, but also the specific gifts they gave each other in their marriage. When they married, they agreed on a “division of power”: Rav Moshe wouldn’t help around the house, but would take care of all the ruchniyus. (Rav Moshe would later remind his talmidim that they had made no such conditions, and they must help their wives.) Over the ensuing years, that arrangement was tested many times, but they adhered to the terms: Rebbetzin Sima assumed all responsibility for the logistics of running their home and raising their family, and Rav Moshe focused on ruchniyus — not only of his family’s, but also that of his town, and eventually that of his yeshivah and Klal Yisrael.

During the early years of marriage, the system that existed in Belarus was that instead of paying the rav a salary, the community would grant the rav a store with a monopoly on a particular item, usually candles or yeast or both, and the residents of the town would then go purchase that item from there, thus suppling the rav with an income. Rav Moshe’s store sold yeast. He was meant to sit behind the counter and man the store, as was done in hundreds of kehillahs, but Rebbetzin Sima told him it was beneath his kavod to do so, and that she would sit and mind the store while he went to learn.

If ever she couldn’t mind the store that day, Rav Moshe would sit there and tell customers to take what they need and then come back and pay when she returned. He had such hakaras hatov that she ran the store for him, and said she had an additional portion in the Torah he learned.

After the Communists shut down all businesses, the community put a surcharge on shechitah, and that surcharge was given to the rav as his parnassah.

Eventually, all rabbanim resigned from their positions, as the government demanded they pay an impossibly high tax for the position of rabbiner. But Rav Moshe never resigned; he felt it would be a chillul Hashem as the Communists would see his resignation as a capitulation to their ideals and make comments about “another Jewish rabbi seeing the light.” With Rebbetzin Sima’s unwavering support, he gave what little money they had to pay the rabbiner tax. Eventually, when they couldn’t afford it, their house was confiscated as payment, and the young family had to share a home with the local shoemaker. Throughout it all, the couple was in agreement: It was worth the price not to make a chillul Hashem.

After over a decade of increasing tension from the Communist authorities, it became clear that the Feinsteins had to leave the Soviet Union. In 1931, Rav Moshe reached out to Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, who had by then moved to Eretz Yisrael. He had a burning desire to head to Artzeinu Hakedoshah. But the British refused his application.

Leaving the Soviet Union required two steps: receiving authorization to leave and being accepted into another country.

The Feinsteins applied for permission to leave, but they were turned down. Apparently, Rav Moshe was already too well known for his brilliance and the Mother Country was reluctant to share home-grown brilliance with anyone else.

In later years, the Leningrad Library featured Rav Moshe’s seforim with an index stating: written by famous Soviet author Moshe Feinstein. They wanted to take all the credit.

Rebbetzin Sima came up with a plan. She advised Rav Moshe to move to Moscow alone for six months, live there in anonymity, and try to obtain visas as a typical Russian, without his Lubanese “rabbiner” title. She would stay in Luban with the children and care for the family on her own, as difficult as that was.

Rebbetzin Sima then reached out to her youngest brother Rav Nechemiah (Kustanovich) Katz, who had left Russia for America years earlier and assumed a rabbinic position in Toledo, Ohio. She asked her brother to help obtain visas for her family. He pulled strings with Senator Robert Taft, son of President William Howard Taft. Taft was friendly with Andrei Gromyko, then the Soviet Union’s foreign minister. Gromyko sent a letter to Moscow asking for permission for the Feinsteins to leave, and visas were issued.

At long last, the visas were in Rav Moshe’s hand. He returned to Luban, and the family packed up to go to Riga, then got the permission to go to America. They remained in Riga for two months.

Before Rav Moshe left the flock he’d led for so many years, he prepared a Hebrew calendar for them meant to last the next 15 years. Unfortunately, within five years, they were all killed by the Nazis in 1942, including Rebbetzin Sima’s father and brothers and their families. Rav Moshe’s brother, Rav Mordechai Feinstein, the rav of Shklov, was sent to his death in Siberia. Two of Rav Moshe’s brothers and his brother-in-law and sister were also killed.

Rav Moshe always reminded his rebbetzin that her binah yeseirah and prescient plan were the reasons, b’chasdei Hashem, they made it out of Europe.

When the boat carrying the Feinsteins docked on American shores, there was a delegation of over 1,000 people, led by Rav Moshe Soloveitchik, waiting to greet them. The Yiddishe newspapers published articles with the headline: “Ari alah mi’Bavel.” The Jewish community was overjoyed at his arrival; they knew they needed him at their helm.

Shortly afterward, three leading rabbanim of the times were involved in a din Torah with a local shochet. In order to give Rav Moshe parnassah, the rabbanim asked him to assist. He heard out the case, examined all the facts… and ruled in favor of the shochet.

The rabbanim were fuming.

The next morning, Rav Moshe woke up to find a line of people forming from their door up the street. They all wanted an honest psak from a rav who wasn’t afraid to say the truth.

T

he Feinsteins initially settled in Brooklyn, New York. But Rav Moshe had a commitment to keep: He had to head to Toledo, Ohio, to help his brother-in-law Rav Nechemiah run the Jewish community. This had been a prerequisite of his visa. How could he leave his wife to navigate a strange new country, foreign language and currency, childcare and running a home, all on her own?

“You go on to Toledo,” the Rebbetzin said with her usual confidence and encouragement. “I will remain in Brooklyn with the children.”

There was a large kiddush to celebrate the arrival of the “new” rabbi in Toledo, and then after two weeks, as per the plan, Rav Moshe returned to his wife and children, leaving the kehillah in the capable hands of his brother-in-law.

Shortly after the Feinsteins arrived in the United States, Rabbi Yehuda Levenberg, father-in-law of Rav Ruderman and one of the pioneer Torah builders in America, excitedly invited Rav Moshe to lead his yeshivah in Cleveland, Ohio.

Reb Moshe accepted Rabbi Levenberg’s invitation. He went alone yet again to try out the position, while his rebbetzin held down the fort. Only a few months later, Rabbi Levenberg passed away. Rav Moshe would have liked to stay and continue leading the yeshivah, but he felt the fundraising aspect was too much for him. He returned to New York.

Rebbetzin Sima then reached out to her cousin, a distinguished and popular local rav named Rav Yosef Adler, who was also the principal of Mesivta Tifereth Jerusalem on the Lower East Side. He asked Rav Moshe to start a beis medrash and semichah program.

One of his original talmidim in Tifereth Jerusalem recalls how Reb Moshe was introduced to them. Rabbi Adler told the students, “Whenever we needed a rosh yeshivah, I brought a great talmid chacham from Europe. Sometimes, I went to Europe myself to recruit people. Baruch Hashem, you boys learn well and, before long, I will have to bring you a new rebbi who knows even more Torah. I’m not a young man anymore, so I decided to bring you someone who knows so much that no matter how much you learn, he will always know more than enough for you.”

Rav Moshe couldn’t afford to travel home from Manhattan to Brooklyn every night, so Rebbetzin Sima advised him to sleep in the beis medrash, wake up early, and wash up in the bathroom — that way no one would know that he wasn’t going home. Rebbetzin Sima didn’t want her cousin to be embarrassed that he couldn’t pay Rav Moshe a higher salary.

Eventually, the family moved to the Lower East Side, but until then, Rav Moshe followed the advice of his eishes chayil.

Rav Adler tragically drowned one year later, and Rav Moshe assumed the leadership of the entire yeshivah. It was this position that Reb Moshe held with such distinction for the rest of his life, another nearly 49 years.

R

av Moshe and his yeshivah quickly became a center of Torah life on the East Side. At its peak, Tifereth Jerusalem enrolled hundreds of talmidim, but it was more than a yeshivah, just as Reb Moshe was more than a rosh yeshivah. He was the Torah presence who dominated the entire area.

At the time, the Lower East Side — with its two million Jews, pushcart wars, bakeries, butchers, and tenement buildings — was the center of Jewish life in America. It housed the Rabbi Jacob Joseph Yeshivah, the Bialystok shul, and Agudas HaRabonim headquarters. It was a thriving hub of humanity, and it was something to behold. In the words of Rav Moshe’s grandson, Rav Mordecai Tendler, “It was a giant shtetl, but the Lower East Side also had a little bit of everything.”

The Feinsteins started out in a tenement building before moving to a co-op on FDR Drive. Rav Moshe’s salary was low, and the Rebbetzin didn’t work outside of keeping home. Every day she stretched the budget to fill their needs, walking ten blocks to Delancey Street to buy better-priced, lower-quality vegetables and day-old bread. Even when they had a bit more money, she still wouldn’t buy fresh bread.

Despite the schlepping and the penny-pinching, she retained her dignity and class; she never complained about having to buy from a pushcart versus the ease of a supermarket. She was grateful for her life and her role in what Rav Moshe did for the klal, and never once complained about their tight finances.

And Rav Moshe, for his part, appreciated her thriftiness; he used to say that when the day-old bread was toasted, you couldn’t taste any difference anyway.

It wasn’t officially called “kiruv” back then, but with his patient and nonjudgmental demeanor, Rav Moshe helped convince many of their neighbors to keep Shabbos and many of the storekeepers working on Canal Street to close their stores on this holy day.

And while the Feinsteins didn’t have much means, whatever they had, they shared with others.

During their years on the Lower East Side, the yeshivah attracted some people who didn’t quite belong anywhere. Rav Moshe brought these people home, and they became part of the household. One man came to the Feinsteins every Shabbos for 25 years. He wasn’t an easy person and had very specific food requests, but not once did Rebbetzin Feinstein comment on the inconvenience; she cooked and catered to him with no complaint or comment.

Rebbetzin Sima likewise opened her home to women in need. Rebbetzin Shifra Tendler, née Feinstein, remembered waking up in the morning and finding a strange woman sleeping in her room. It was just routine to welcome strangers into the home.

When all the beds for sleepover guests were taken, Rebbetzin Sima took the doors off their hinges, laid them on the floor, and covered them in blankets for whoever needed a place to sleep. Every morning, the doors were returned to their places.

The family and their guests were crammed together like sardines, but no one complained. Klal Yisrael were putting themselves back together after the Holocaust. The Feinsteins had escaped Europe and gave whatever they could to those survivors who hadn’t been as fortunate.

TO

the public, Rav Moshe was a leader who belonged to Klal Yisrael; his vast Torah knowledge, unmatched halachic insight, and far-reaching vision were employed to guide intimate individual decisions as well as communal, medical, and religious policy. But during the immediate postwar years, Rav Moshe’s greatest area of expertise was agunos. He would enter the beis medrash, pull aside two talmidim, and have them join as members of his beis din to matir an agunah.

“It must have happened two thousand times,” an MTJ talmid once remarked to a grandson. The grandson, thinking the number was exaggerated, checked with Rav Moshe.

Rav Moshe laughed sadly and said, “Much more than that.”

Through this wrenching process, he changed the fabric of Klal Yisrael. The freed women were able to rebuild, to start over; how many thousands of descendants currently exist based on his holy psak?

Rav Moshe also refurbished the mikveh on the Lower East Side, without public fanfare, based on nickel-and-dime donations. Other rabbanim may have dismissed America as a place of no hope and no future, but he believed that he could transform the treifeh medinah into a makom Torah.

INtheir apartment at 455 FDR Drive, Rav Moshe was a focused and devoted husband who set aside his communal role to focus on his rebbetzin. They conversed in Yiddish, and created an entire world together.

Before mealtimes, Rebbetzin Sima sometimes had to call him to the table repeatedly; he was so engrossed in his learning or writing that he wouldn’t hear her. But once he came to the table, he never brought a sefer with him or answered a phone call; he was present and focused on his family during meal times. He did learn sifrei halachah with children during mealtimes, mostly Chayei Adam.

When it was just the two of them at home, all three meal times were centered around the Rebbetzin, and they weren’t quick affairs. Rav Moshe and the Rebbetzin discussed the children and grandchildren, local happenings, news. The Rebbetzin shared stories and tidbits she read in the local Jewish paper and Rav Moshe listened intently. They shared jokes and laughed together; but one thing they never discussed was lashon hara.

Their breakfast was usually oatmeal, occasionally farina, made with water, not milk, as that was too expensive. No sugar. A grapefruit. And of course, a coffee. Lunch was an egg or leftover gefilte fish; they didn’t wash for hamotzi. A typical supper was an eighth of a chicken, leftover cholent and leftover tzimmes, or leftover fricassee from Shabbos, made up of chicken necks and pupiks cooked in tomato sauce. It was accompanied by a glass of apple juice or orange juice, followed by tea and compote.

For a midday snack, Rebbetzin Sima brought Rav Moshe tea or coffee with cut-up fruit or a cookie from the neighbors.

Rav Moshe never showed impatience, never rushed her. He was grateful for the food she made for him, for the spotless home she kept, where one could literally eat off the floors and the shades and drapes were updated every few years.

When she’d go away for a night here or there, he would fry himself some eggs and then wash all the dirty dishes, not wanting her to come home to a full sink. When she underwent a medical issue, he put aside the thousands of things he was busy with and attended the doctors’ visits at her side.

In some marriages, the public show of formality is replaced by casual interactions in private. That was never the case for Rav Moshe and Rebbetzin Sima. They demonstrated absolute respect for one another — in public and in private.

In front of others, Rebbetzin Sima referred to her husband only as “Rabbi Feinstein.” His kavod was important to her, and she ensured that he never left the house unless his clothing and shoes were absolutely spotless and perfectly ironed.

Until her last days, Rebbetzin Sima was immaculate at all times, complete with makeup, sheitel, and perfume. It was important to her, the Princess of Luban, and Rav Moshe appreciated her efforts as well. She kept it up even after he was niftar; it’s how she felt a bas Yisrael should present herself.

Rav Moshe would sometimes spend weeks writing a teshuvah, writing and rewriting and crossing things out until he felt it was ready to send it out. But if his rebbetzin saw the paper with all of its cross-outs, she made it clear that a clean copy was more befitting her husband’s stature. Rav Moshe would then sometimes spend another two weeks rewriting a 30-page teshuvah until it was immaculate.

Rav Moshe was very makpid on his wife’s kavod. He may have been a very public person, but his home was also the Rebbetzin’s dominion, and he never accepted visitors without clearing it with her first. The only time Rav Moshe ever showed anger to any of his children was when he heard one of his sons speaking disrespectfully to his mother. Just as she considered his kavod sacrosanct, he felt the same about hers. They both felt it was a true zechus to be married to each other, and their actions reflected this for their 65 years of marriage.

A

long with those high standards and extreme respect, it was undeniable that the Rav and Rebbetzin simply enjoyed being together. Every day, for decades, they would take a stroll around the neighborhood park and then go into the candy store on the corner, buy glasses of soda, and drink them right there. Whether in the cold or the heat, they went on their walk, greeting the neighbors and inhabitants of the area.

At Rav Moshe’s levayah, people of all ethnicities cried for the rabbi who would no longer wish them a good morning on his daily stroll.

In the summers, Rav Moshe and Rebbetzin Sima traveled to a different locale for a week or two for a change of scenery. Twice, they took the long trip to the White Mountains in Vermont because the Rebbetzin had heard that they were very beautiful. The trip may have been a long one, but Rav Moshe, it wasn’t a question. If Rebbetzin Sima wanted to go, then they went.

The Rebbetzin lit five candles every Erev Shabbos, different from the common practice of lighting two candles with an additional candle for every child. After she lit them, Rav Moshe would carry her candelabra into his study, and after the Shabbos meal concluded, he’d learn his holy, holy Torah to the light of his treasured wife’s beautiful candles.

Fully Invested

Rav Shmuel and Rebbetzin Temi Kamenetsky

Rebbetzin Temi cheerfully held down the fort as Rav Shmuel built a Torah citadel in Philadelphia. They were in it together — and whenever his schedule allowed it, he was a hands-on husband and father who saw it as a privilege to lighten her load

On the surface, it seemed an unlikely shidduch.

The chassan was European-born. The child of an acknowledged litvisher gadol and leader, he’d already gained a name for his prodigious Torah knowledge. The kallah was a child of Williamsburg; she knew a Poilishe Yiddish, and the concept of full-time learning was far from a given in her circles.

But when young Rav Shmuel Kamenetsky got engaged to Temi Brooks, it all made perfect sense. The two families had already established an enduring link that began Temi’s father, when businessman and chazzan Reb Mordechai Brooks, learned that the great talmid chacham, Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, would be arriving in New York to join the hanhalah of Yeshiva Torah Vodaath. Reb Mordechai promptly packed up his family and moved out of his own home, graciously offering it to the Kamenetskys. He accidentally left behind a set of candlesticks and told Rav Yaakov to enjoy them.

When the shidduch between their children was finalized, those candlesticks were a tangible expression of the already-existing bond.

T

emi had learned in Rebbetzin Vichna Kaplan’s seminary and was one of the very small group of young women determined to marry a ben Torah. The new couple set up their home in Lakewood, New Jersey, where Rav Aharon Kotler had formed a small, select kollel — an anomaly in America back then.

While Rav Aharon didn’t insist that his talmidim assume rabbinical positions — kollel was an end unto itself — Rav Shmuel felt that the young generation needed more high-level yeshivos. He spent some time in Los Angeles helping Rav Simcha Wasserman in the yeshivah he established there. His next stop — the destination where he actualized his vision — was Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Rebbetzin Kamenetsky stayed in New York during Rav Shmuel’s Los Angeles years. But when the Philadelphia option came up, it was clear that the entire family would go along. At the time, the Kamenetskys had two small children. The chinuch options in Philadelphia weren’t the best fit for their standards, and they consulted Rav Aharon for advice.

“If you do for the Eibeshter’s kinder,” Rav Aharon promised them, “He takes care of your kinder, you don’t lose out. The Ribbono shel Olam pays back.”

And so the Kamenetskys settled in Philadelphia.

T

hey settled in an area called Strawberry Mansion, which, as sweet as it sounded, was far from the best setting for a frum family. There were no suitable playmates for the children, no babysitting groups.

“My mother knew she was headed to a midbar,” her daughter Rebbetzin Malka Kelemer says, “and she went in with eyes wide open.”

It was mesirus nefesh, but she was prepared to follow her husband b’lev ub’nefesh.

The family didn’t have a car, so there wouldn’t be frequent drives back home to see the family. “Nothing was convenient there, you needed a bus to get just about anywhere,” her daughter Rebbetzin Ettil Berkowitz remembers.

A few years later, they moved to a house closer to the yeshivah, surrounded by the other rabbanim and their families.

The local residents more than made up for the lack of family. The wives of the balabatim living nearby were called tantes as well. “To us children, Rebbetzin Svei was Tanta Judy. So many of the others — Rebbetzin Stefansky, Rebbetzin Mandelbaum, Rebbetzin Golombeck, and Rebbetzin Taub — were tantes as well,” recall the Kamenestsky daughters, Rebbetzin Miriam Schechter, Rebbetzin Ettil Berkowitz, Rebbetzin Shoshana Moskowitz, and Rebbetzin Malka Kelemer.

With time, the community melded into one, tightknit family unit.

Through the yeshivah, the frum residents received kosher bread and chalav Yisrael milk, as well as meat and chicken. Somebody delivered eggs regularly. Any other groceries had to be obtained by scouring the shelves of local supermarkets for kosher items.

Rebbetzin Temi was very busy in the community. She performed kiruv before it was even the trend, learning with college students and people in the process of becoming frum, teaching kallos and hosting sheva brachos.

There was no new clothing, no shopping, just making do with what they had. The Rebbetzin, who was talented and handy, sewed clothing for herself and her girls, and made summer curtains, winter curtains, and doll clothing for the children with the extra scraps of material.

Rav Shmuel devoted endless hours and effort to his fledgling yeshivah. At the same time, his young family was quickly growing. He needed an energetic and devoted partner holding down the home front in order to focus on the yeshivah during this period. And Rebbetzin Temi more than met the description.

The Kamenetsky family’s first home was far from the yeshivah. Rav Shmuel’s daily commute involved two train rides plus one bus ride. On Shabbos — when he needed to walk an hour each way — he sometimes left his home before Shacharis and returned only after Shabbos. The Rebbetzin was left alone with her growing family of boisterous children all day. And whenever he took trips to New York on behalf of the yeshivah, she managed the household and children on her own. But she never complained — she always had a song on her lips, and a light, positive manner.

Rebbetzin Temi knew that even if he wasn’t always present, Rav Shmuel was fully invested in both her and the children. Whenever he was away, Rav Shmuel called her to check how she was managing without him. And whenever his schedule allowed it, he was a hands-on father who did whatever he could to help out.

“Our father wasn’t around that much. He was an extremely busy man,” remember the Kamenetsky daughters. “But when he was home, he was always a tremendous help with the household. Today, busy men argue their place is not in the kitchen or sweeping, but our father didn’t see it that way.”

Rav Shmuel used to wake up very early to learn and prepare shiur, and allow Rebbetzin Temi, who usually had a baby in her bed, to sleep until at least 7:15. During those early morning hours, he gave the children breakfast, feeding them and then cleaning up, so that Rebbetzin Temi wouldn’t be greeted by a messy kitchen. He also made sure the children were ready for school before he left for yeshivah.

“We thought our mother ‘slept late,’ ” Rebbetzin Berkowitz remembers fondly.

“Back when we were little,” one of his daughters recounts, “he used to hurry home during a break in yeshivah to help out during supper time. He helped feed the little ones and put them to bed, and then he rushed back to yeshivah.”

And while Rebbetzin Temi kept an immaculate home, Rav Shmuel was involved in things like ordering the meat and stocking the freezer. Whenever he stepped in, she’d say, “You’re the best!”

T

he Kamenetsky children never saw their parents argue or disagree. They only learned later on that strife could exist between spouses. “For the 72 years they were married, my father never established himself as ‘the boss,’ ” says Rebbetzin Moskowitz. “He never had to have the last word. He’s a tremendous mevater.”

All the Kamenetsky daughters agree: vatranus was the key to their parents’ legendary shalom bayis.

Rebbetzin Temi showed the same deference to him. “Anything we asked him, he’d say, ‘Ask Mommy.’ And anything we asked her, she’d say, ‘Check with Abba.’ Anything anyone asked her, Mommy would answer, ‘I need to check with my husband.’ ”

It was obvious to all who knew them how much they respected each other. In the summers, the family went on day trips. Rav Shmuel would have been happy to stay home and learn, but he knew it meant a lot to Rebbetzin Temi to take the children out — so they would go to a nice park, and the children played contentedly while Rav Shmuel took out a sefer and Rebbetzin Temi, her mending.

Rebbetzin Temi was a woman years ahead of her time. She taught herself about wellness and healthy eating, researching the dangers of ultra-processed foods, and revamped her cooking and lifestyle as a result of her new knowledge. She only used whole wheat, never touched margarine, ate wheat germ and raisins, bought vitamins and supplements. And Rav Shmuel went along with it all, never questioning, his agreement a testament to his trust in her.

R

ebbetzin Temi possessed a keen and inquisitive mind and had impressive Torah knowledge. She was an expert in dikduk and would often quote Chazal and pesukim from Tanach.

In a letter she wrote to her then-chassan during her engagement, she informed him that she had completed studying Iyov and Mishlei as per his suggestion, and asked what she should learn next.

It was a precursor of the happy hours spent learning together as a married couple. “We remember them learning together,” their daughters share. “On Pesach it was Shir Hashirim, during the summer it was Pirkei Avos, and on Succos it was Koheles.”

For his part, the Rosh Yeshivah greatly respected her intuition and insight. When couples came to discuss shalom bayis, Rav Shmuel often asked the Rebbetzin to join the conversation and share her thoughts. And when a well-known lecturer on marriage called Rav Shmuel, asking for guidance, Rav Shmuel referred her to the Rebbetzin. Amazingly — or perhaps it should have been expected, for a couple so in sync with one another — the Rebbetzin’s opinions lined up exactly with various instructions the lecturer had received from Rav Shmuel over the years.

Rebbetzin Berkowitz fondly shares a story told to her by Rav Brustowsky, who was the gabbai of the yeshivah forty or so years ago. “The talmidim would chip in every Chanukah to buy the Rosh Yeshivah a gift, mostly seforim, but we would ask the Rosh Yeshivah what he wanted each time. One year, he answered, ‘A candelabra for the Rebbetzin.’ So the boys went out and purchased a beautiful candelabra. They showed it to the Rav, who said to Rav Brustowsky, ‘Okay, but you need to come with me when we give it to the Rebbetzin.’ They hurried home together and presented the gift. The Rebbetzin’s immediate reaction was, ‘How many times do I have to say, this gift is supposed to be for the Rosh Yeshivah! To show hakaras hatov to you!’ Rav Kamenetsky shrugged and said, ‘I know, Temi, but I couldn’t help myself.’ ”

The Rebbetzin was a very vibrant and spritely woman who moved so quickly people would say she ran rather than walked. “Well, I have to keep up with my husband,” she would retort Rav Shmuel is known for belying his years with his youthful and energetic manner.

But she saw a deeper element to that, too. In the months before her passing, she focused on a particular message: If one never hurts another, she said, he will grow old with all his faculties intact. Her proof? Her husband, Rav Shmuel, whom she says she never saw get angry. (Her own mind likewise remained clear until the day she was nifteres.)

Rav Brustowsky shared as well that the Rebbetzin once said to him, “It’s a pleasure to live life with a person who never, ever gets angry.” When he shared this quote with Rav Kamenetsky at the shivah for the Rebbetzin, the Rav said, “It takes one to know one.”

R

ebbetzin Temi was thrilled to share her life with a serious ben Torah. She probably didn’t expect him to become the leader of an entire continent’s Jewry. Still, when the world “discovered” Rav Shmuel and he became an address for problems, questions, and initiatives, Rebbetzin Temi never resented sharing her husband. She opened her home and heart to the visitors who sat around her table seeking advice, and she never screened calls or took the phone off the hook, even though calls came in at all hours of the day and night.

A neighbor once called to speak to the Rosh Yeshivah. The Rebbetzin mentioned that he was eating, and began to pass the phone, but the caller protested: He’d call back later. “Why? Does the Rosh Yeshivah eat with his ears?” asked the Rebbetzin.

Much as Rav Shmuel broadcast a measured calm, Rebbetzin Kamenetsky radiated happiness and gratitude. She voiced even mundane requests in a singsong and filled her home with light and joy. It was clear that she considered herself the most fortunate woman.

When people asked her what it felt like to be married to a rosh yeshivah and gadol, she said, “I don’t feel different from anyone else. It’s interesting though, we say in Ashrei, ‘Posei’ach es yadecha u’masbia l’chol chai ratzon.’ Hashem is our loving Father, and every father wants to see his children happy. Hashem gives you that sensation of wanting something so that you’ll enjoy it when you get it! Even when I was younger, I always loved hearing bochurim learning, the kol Torah. So my loving Father gave that to me — I get to hear Torah all the time.”

“Once, when I was around seven years old,” Rebbetzin Kelemer remembers, “my mother said to me, ‘Abba is the best man in the whole world.’

“I answered her, ‘Well, to me he’s the best man, because he’s my father. But you probably think your father is the best man.’

“But Mommy smiled and just repeated, ‘Abba is the best.’ ”

A Nation’s Address

Rav Chaim and Rebbetzin Batsheva Kanievsky

They came from different backgrounds and had different personalities, but Rav Chaim and Rebbetzin Batsheva became twin pillars for their people, working to hold up the masses of Jews who streamed to their small, simple home every day

It wasn’t a very auspicious first meeting.

When Rav Chaim Kanievsky, the brilliant son of the Steipler Gaon, met young Batsheva Esther Elyashiv in late 1951, he wasn’t quite sure what to say.

At first, there was a discomfiting silence. Then he ventured a question he was curious about: “So what’s your father learning these days?”

The shidduch proceeded, and soon enough the young couple learned their own shared language. Over a blessed marriage spanning decades, they became so attuned to one another that Rebbetzin Batsheva shaped her daily schedule around her husband’s priorities, and Rav Chaim often remarked, “I learn much better when you’re here in the house with me.”

Rebbetzin Batsheva treasured “her Chaim” long before the wider world came to appreciate the living sefer Torah in its midst. With a smile that made it look effortless, she shouldered all their physical concerns, allowing her husband to focus exclusively on ruchniyus. And while Rav Chaim’s singular focus never changed throughout his long life, he demonstrated in ways both nuanced and overt how much he valued his wife. Eventually the two became something like twin pillars for their people; with different personalities and strengths, they worked in partnership to sustain and rejuvenate the masses of Jews who streamed to their small, simple home every day searching for something that only the Kanievskys could provide.

S

hanah rishonah wasn’t easy for young Batsheva. She came from a large, loving family in Yerushalayim, and wasn’t familiar with the quiet Bnei Brak of then. Her father, Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv, was an undisputed posek and gadol whose approach she had absorbed throughout her childhood; her new husband, however, followed the derech of his uncle the Chazon Ish. It was a real adjustment.

Unlike most new brides, she didn’t make the trip back home very often. Bnei Brak wasn’t the easy bus ride from Yerushalayim that it is today; the trip required multiple buses and a train ride. But Bnei Brak was where Rav Chaim learned best, and so that’s where she wanted to be.

During that first year, Rav and Rebbetzin Elyashiv gifted Rebbetzin Batsheva some funds for clothing and other things a new wife might need. Knowing her husband didn’t yet have a large Shas, Rebbetzin Batsheva handed the money over to Rav Chaim.

“I don’t need new clothing,” she said. “I need you to have the seforim you enjoy.”

Rav Chaim learned from that Shas all the years of their marriage, filling the margins with his comments and chiddushim. And he gave it a name: the “Rabbanit Shas.”

As a yungerman in Kollel Chazon Ish, Rav Chaim wanted to start a gemach for short-term loans. He greatly desired to help those in need, but he had no extra funds. The Rebbetzin, knowing how important it was to him, took some of the earnings from her two jobs — secretary and teacher — and put the money aside for his gemach.

In appreciation, he named the gemach Chasdei Batsheva. “It wasn’t a vague hint or some poetic allusion,” their grandson, Reb Yanky Kanievsky, notes. “His appreciation was out in the open: Chasdei Batsheva.”

E

ven as Rav Chaim mastered more and more Torah and wrote more seforim, he was a very attentive and involved father who was extremely present in the lives of his eight children.

His children remember how he learned with each of his sons, carried them on his shoulders, and closely monitored their development. He even played games of his own invention with the little ones on the long, dark Friday nights — they’d quote maamarei Chazal and he’d name the source, or they’d name a sefer and he’d tell them exactly where it was situated on the multiple bookshelves flanking the walls.

“In contrast to what you may have expected or heard, my father was always a family man,” his son Rav Avraham Yeshaya says. “Until his very last day, he was always with us, and we were always at his side.”

But it wasn’t only his children who benefited from his attention and care. Over the years, the house became a vibrant, busy address where the entire spectrum of Jewry could find advice, encouragement, and brachos.

Rav Chaim commanded respect and adulation from across the spectrum of Torah Jewry, but he didn’t actually hold an official public position. He spent virtually his entire day at home, learning, writing his ground-breaking seforim, and helping so many Jews who streamed to 23 Rashbam Street. Eventually Rav Chaim he became one of the gedolim most known and accessible to the public. He had kabbalat kahal hours every single day, served as sandek whenever asked, and answered every one of the piles of letters he received.

And Rebbetzin Batsheva was there the entire time, facilitating, easing, and even serving as a parallel partner — albeit with her own very warm, emotional, motherly style.

Only after his chovos — the learning obligations he set for himself — sefer writing, and mail-in questions were completed did Rav Chaim begin his kabbalat kahal. People came from around the world seeking his advice or his brachos. He was known to burst into tears while listening to the pain that some Jews carried. Rav Chaim valued his time to the extent that in to save precious seconds, he invented the word “Boo-ha,” an acronym for “blessings and success.”

At appointed times each day, the steep staircase outside their home was packed with visitors waiting to enter. Thousands would wait for their moment with either the Rav or Rebbetzin, a chance to unburden themselves, to glean advice, or just a word of chizuk to carry them through.

Amid all the busyness, and despite the open-door atmosphere, Rav Chaim and Rebbetzin Batsheva carved out time for a private meal — just the two of them — twice a day. Lunch was served in Rav Chaim’s seforim room, and supper was in the kitchen.

Rav Chaim was a very punctual person and his “chovos” demanded extreme rigor and barely a moment of idle time. They certainly didn’t leave him much time for eating. Rebbetzin Batsheva, however, had a very soft heart, and she often needed extra time to offer that last bit of comfort or encouragement to the women who came each day to pour out their hearts. Yet Rav Chaim would never consider beginning to eat without her. Instead, he found a solution for the wait: either he learned special limudim earmarked just for these waiting periods or he used the time to answer the most challenging letters he’d received: correspondences from Rav Dov Landau, Rav Elchanan Berlin, and other great talmidei chachamim.

The meals took 15 minutes. Rebbetzin Batsheva updated him on family happenings, engagements, births. She asked him questions people sent her, and occasionally they discussed ideas for shidduchim (Rav Chaim actually redt many successful shidduchim over the years). She did most of the talking; he gave brief responses. But as one rebbi in the Mir tells chassanim, in those 15 minutes, you witnessed true love. He would look into her eyes as she spoke, bestowing his full attention on his wife.

After the Rebbetzin was niftar, he never went into the kitchen anymore, aside from when performing bedikas chometz. He no longer had a reason to.

M

uch of the Kanievskys’ daily scheduled revolved around the nearby Lederman shul, where both Rav Chaim and the Rebbetzin davened. The Rebbetzin often told women to daven Minchah there with her, and then they could accompany her home and get some personal time. The shul even constructed a special walkway to ease Rav Chaim’s short walk.

But during the last three decades of his life, he made a new arrangement for Simchas Torah, since he no longer had the strength to stand with the sefer Torah for too long and could no longer do all seven hakafos in the Lederman shul. Instead, he stayed for the first hakafah and then returned home, where a more intimate minyan awaited him to complete the hakafos and davening.

Rebbetzin Batsheva did everything along with Rav Chaim: She accompanied him to virtually every bris he attended, woke up for vasikin just as he did, had a hot Melaveh Malkah meal waiting right after Havdalah…. But this Simchas Torah at home was one thing she couldn’t do. She couldn’t give up the beautiful, extensive hakafos at the Lederman shul. And so she remained there until the end of the very last hakafah.

Back at home, long past the conclusion of their own hakafos, Rav Chaim’s children encouraged him to make Kiddush and eat something. “It’s getting late, and surely Sabba has to eat something,” they said. “We’ll make Kiddush for Savta when she comes.”

But Rav Chaim wouldn’t hear of it. He sat and learned peacefully until Rebbetzin Batsheva returned home.

On Chol Hamoed, Rav Chaim and Rebbetzin Batsheva traveled to Yerushalayim to visit the Elyashivs. “Abba,” Rebbetzin Batsheva told her father proudly, “you have to see how many people turn to Rav Chaim! How many people come to his shiurim! How many people write him for eitzos!” She wanted her father to join in her nachas.

After visiting the Elyashivs, they proceeded to the Kosel. The moment they stepped out of the car, they were immediately surrounded by those in need of a brachah or chizuk. In her warm and very personal manner, Rebbetzin Batsheva bestowed her full attention on each and every woman who approached her. Rav Chaim, who spoke briefly, found himself back in the car long before she was done.

Again, his family would urge him to return home, explaining there were tens of people who would jump at the privilege of driving the Rebbetzin back home. But Rav Chaim wouldn’t budge.

“After Savta was suddenly niftar,” reminisces their grandson Reb Yanky Kanievsky, “the first thing Sabba said to Abba was ‘Mi yidag li? Who will look after me?’ ”

As long as she’d been there alongside him, his every need was filled. She shaped her schedule and priorities around his own to the degree that he didn’t even have to think what time of day it was. She was the trusted “shomer” who supervised her husband every Shabbos while he studied by the light of a kerosene “luxe” lamp, she woke up before sunrise and joined him for tefillos in the Lederman shul, she reminded him of his daily tasks and commitments, and refused to allow him to do so much as to prepare a cup of tea. She allowed him to live in a Gan Eden of Torah learning even while here on Earth.

And he never forgot where his success came from.

Early in their marriage, when the children were still small, Rebbetzin Batsheva was once sick. She dispatched her oldest son, Rav Avraham Yeshaya, to her father-in-law, the Steipler Gaon.

“Ima is asking for a brachah for a refuah sheleimah; she’s not feeling well,” the little boy said.

The Steipler’s eyes widened and he exclaimed, “She is asking me for a brachah? Her brachos are much more powerful than mine! She performs chasadim that I could never do!”

Then the Steipler began to describe to the little boy how his mother would host lonely, elderly women in her home, giving them food and drink without any remuneration, and sometimes even endure getting cursed and verbally abused in return.

“I couldn’t do such things,” the Steipler concluded, “so her brachos are much better.”

When young Avraham Yeshaya returned home, he told Rav Chaim that the Steipler had said Rebbetzin Batsheva’s brachos were worth much more than his own. Rav Chaim took the words very seriously, and after that, he asked his wife for a brachah every year before going to Kol Nidrei on Erev Yom Kippur. Not only that, but also on Erev Pesach, before he went to bake matzos, he would ask for her brachah for the matzos to turn out mehudar.

One year, he forgot to ask and the matzah baking was unsuccessful. “You see?” he said. “We weren’t zocheh to our usual success, because I didn’t ask Ima for a brachah.”

Elisheva Appel contributed reporting to this piece.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 939)

Oops! We could not locate your form.