In Record Numbers

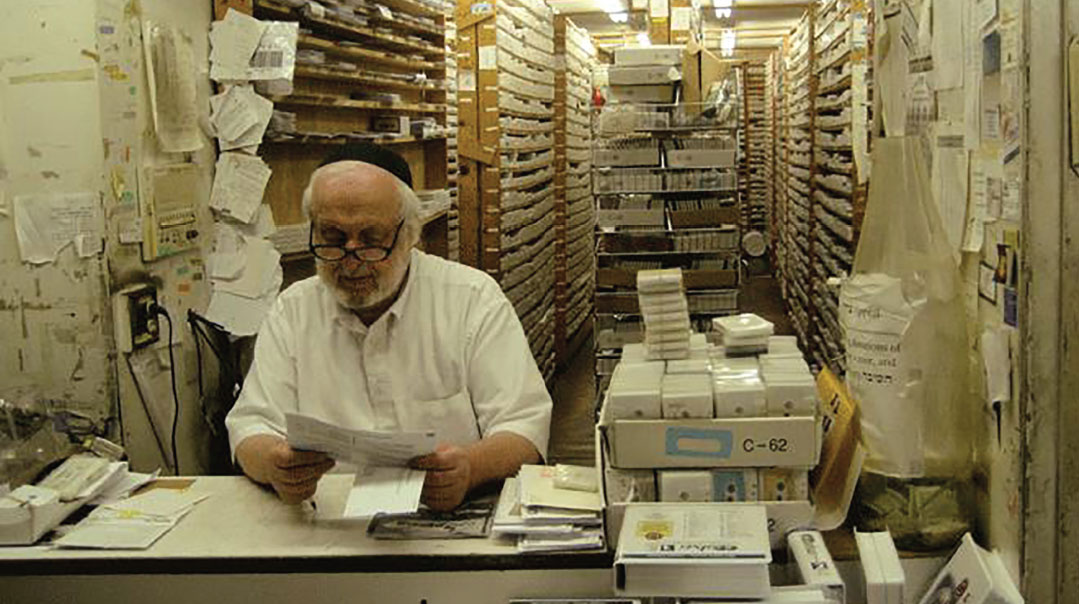

Rabbi Mayer Apfelbaum’s Boro Park basement housed reels of Torah treasures

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab

F

iftieth Street near 18th Avenue is one of Boro Park’s busiest corners, and Erev Rosh Hashanah is one of the Jewish year’s busiest days. Yet just hours before the year 5779 turned into 5780, the intersection came to a standstill.

The reason? A levayah was taking place outside the modest Apfelbaum home, where the monumental Torah Tapes enterprise was located for decades. Its founder, Mayer Apfelbaum, had expressed the wish that after his passing his aron be brought to his house, so that the Torah that had flowed forth like an endless river from its portals to multitudes of Jews could accompany him on his last journey. And so, for a half-hour, the frenetic Erev Yom Tov activity ground to a halt as Boro Park paid a tearful tribute to one of its noblest citizens.

Mayer Dovid Apfelbaum was born in the pre-war Galician-Polish town of Hermanova, not far from Lizhensk. With his father barely eking out a living as a peddler of wares, Mayer and his five siblings often made due with a soup his mother would make from nothing more than potato peels. Once, the family procured a treasure — an orange! — which their mother promptly divided up for her children to feast on.

Mayer and his brother would travel to an uncle of theirs in another town who was well-off enough to hire a melamed for his children, spending days or weeks at a time with their cousins there. In the fall of 1939, the Apfelbaum brothers were on their way to their uncle’s town when war broke out, making it impossible to reach their destination, or to return home. Never again would they see their parents and siblings, all of whom, together with virtually every other Jew in their hometown, perished at the hands of the Nazis.

The boys spent two years on the run until one day, they split up to look for food. Mayer’s brother never returned, and after several days, little Mayer had no choice but to take the refuge offered him by a childless non-Jewish couple who, not realizing he was Jewish, allowed him to stay in their barn. They’d try to take him to church on Sundays, which Mayer avoided by offering to stay home and take care of their wild-spirited cow.

Once the couple discovered that he was a Jew, the wife decided to report him to the local Gestapo, thereby hoping to earn extra rations. Each time the Nazis came looking for him, however, Mayer managed a miraculous escape under their very noses. Once he hid in a chicken coop, and another time he clambered up into high branches, with the German policeman paying no heed to the search dog barking excitedly at the foot of the tree.

On yet another occasion, Mayer heard the wife plotting to get him drunk and put him out in the cold to freeze to death. The quick-thinking boy wrote a letter, allegedly from a relative of his, which he slipped under their door — it stated that this “relative” knew the boy was living with the couple and he’d hold them responsible should anything happen to him.

Finally, at age nine, Mayer was apprehended and taken to a detention camp, the first of 11 different such Nazi Gehenna he would experience during the war years. His eventual liberation in 1945 came from Bergen-Belsen at the hands of British forces.

The well-meaning soldiers distributed to the frail inmates cans of meat, cookies, and candies, not realizing this would lead to the deaths of many who hungrily devoured these rations, causing their emaciated stomachs to explode. When Mayer, too, ate his fill, he fell unconscious and was taken for dead. As he was being removed for burial, a British doctor exclaimed, “This one still has a pulse!” and he was brought back among the living.

After spending months in a hospital recovering from tuberculosis and other illnesses, Mayer was shipped off to a kinder lager (a Jewish children’s internment camp) in Sweden. The peyos he insisted on growing, tucked behind his ears, told those in charge that he was from a religious home, and they put him under the care of Agudah representatives rather than secular Zionist ones. To this day, the Apfelbaum offspring keep peyos behind their ears in recognition of the role that played in shaping Mayer’s life.

Eventually, a distant cousin living in Boston sponsored Mayer’s emigration to the United States, and he arrived on these shores in 1947, an orphan in his early teens, alone. Enrolling in Yeshiva Torah Vodaath in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, Mayer started out in an alef-beis class, progressing from there to mesivta and then beis medrash, where he learned under Rav Aharon Yeshaya Shapiro and Rav Eliyahu Moshe Shisgal. Rosh Yeshivah Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky also took a special interest in the young man.

It was in Torah Vodaath that he met one of his life’s formative influences, Rabbi Moshe Rivlin, who was in charge of the yeshivah’s dormitory. Gershon Rothstein, who hails from Portland, Maine, and is a grandson-in-law of the legendary menahel of Torah Vodaath, Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz, remembers how “Reb Moshe Rivlin was mamash a father to us, and Mayer became a ben bayis at the Rivlin home, eating the Shabbos meals with them for 14 years until his marriage. It was Rabbi Rivlin who eventually walked Mayer down to the chuppah.”

Mr. Rothstein recalls that very early on, Mayer’s propensities for chesed were abundantly evident. “As a bochur, Mayer operated the canteen in yeshivah, where the guys were able to get something to eat even when the kitchen wasn’t open. I can’t tell you how many bochurim he ‘took care of.’ They’d tell him to put it on the bill but he’d never ask them to pay their bills.” Rabbi Nosson Scherman, a friend of Mayer since their yeshivah days, recalls that Mayer “would give older boys the key to the canteen so that they could grab a nosh after a long night seder, and pay him the next day, or whenever they could.”

As a young orphan with no family support system, Mayer experienced difficulty in finding a shidduch and in his early twenties, he was advised to travel to Eretz Yisrael in search of his bashert. This was the 1950s, when international air travel was a rarity. Those traveling abroad usually got a big sendoff, but Mayer headed off to the airport alone, not expecting anyone to see him off on the long journey overseas.

When he got to the airport, he was taken aback to find a fellow Torah Vodaath talmid, Luzer Flam, waiting for him. He asked Luzer why he had come, and Luzer replied that he couldn’t let Mayer go off without anyone there to say goodbye. Mayer’s trip to Eretz Yisrael didn’t make him a chassan, but the brief encounter at the airport was to become a turning point in his life.

Luzer Flam got engaged soon after Mayer’s return, but just three weeks later, tragedy struck: He was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. His condition deteriorated to the point that he became a long-term patient in the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in Crown Heights, and Mayer decided it was time to repay the kindness Luzer had shown him.

Determined to help Luzer continue learning Torah despite his debilitating disease, Mayer began recording shiurim for him, some of them given by Torah Vodaath rebbeim and others made specially for Luzer by his yeshivah friends. It was this fledgling effort that would eventually develop into Torah Tapes, the Torah-dissemination powerhouse to which Mayer devoted so many decades of his life.

The cost of a private nurse to care for Luzer in the hospital was exorbitant, but Mayer decided he would raise the funds for it. But how? He became a shadchan, charging a minimum of $1,000 when he was successful. At those rates, making just one or two shidduchim a year produced enough income to pay for the nurse.

On Lag B’omer of 1960, Mayer married Miriam Dina Schneider, a Bronx girl whose family had been in America for generations. Her grandfather was one of those heroic Jews who passed the nisayon of shemiras Shabbos by becoming a house painter. The couple settled on Hewes Street in Williamsburg, around the corner from Torah Vodaath, and Gershon Rothstein became their “Shabbos bochur” until his own marriage three years later. One Erev Shabbos, Mr. Rothstein recalls, “Mayer called me to say, ‘I can’t be home this Shabbos because my wife is having a baby, but I’ve prepared the whole Shabbos for you. Just go in and the Shabbos will be there.’ That’s the way Mayer Apfelbaum worked.”

Although Luzer Flam passed away in the late 1960s, the chesed his illness spawned continued on. Mayer continued his involvement in shidduchim with a passion, but with one big difference — his fee for making a successful match changed to a flat rate of $18, no matter how much more they could afford to pay. Before redting a shidduch, he would inform the parties that this is what he charged and no amount of arguing with him could change his mind. In all, Mayer was responsible for bringing well over one hundred couples to the chuppah.

Mr. Rothstein says he used to go to Mayer’s home every Purim “to bring mishloach manos, although of course, Mayer would take the opportunity to give me money to distribute to various needy individuals. It was such a pleasure to watch as the people whose shidduchim he had made would come to visit with their children, whom he treated like they were his own.”

Not content to merely make shidduch suggestions, Mayer would spend countless hours on the phone cajoling and convincing the skeptical, the timid, and the burned-out that his idea could work. He was fearless, not shying away from calling anyone to redt any shidduch he thought had a chance of success. He knew his name carried weight with people and he used his sterling reputation to his advantage, telling people they couldn’t let him down or make him look bad by declining to give his idea a try.

His efforts went beyond just setting up dates, too. If necessary, he’d outfit a prospective suitor with a full wardrobe to ensure he looked presentable. And if he succeeded in making a match and both sides were of very limited means, he’d pay for part of the wedding himself.

Meanwhile, the amateur tape-production effort begun by a few bochurim on behalf of an ailing classmate had continued to grow, with more and more people asking for tapes on an ever-wider range of topics. In 1970, it began operating officially under the Torah Tapes name out of a dormitory room in Torah Vodaath. Later, it took a quantum leap when it moved into permanent headquarters that occupied two floors of the Apfelbaum home on Boro Park’s Fiftieth Street.

With time, Torah Tapes — a treasure trove of cassettes ranging from both daf yomi and iyun shiurim in Gemara and Mishnayos to story tapes and history tapes — grew into a mammoth harbatzas Torah operation that over the years, estimates his son Mendy Apfelbaum, “has been responsible for well over ten million blatt Gemara being learned. You can do the math: For decades, Torah Tapes employees produced an average of 26 tapes every three minutes, 16 hours a day.” Mendy remembers a day in 1985 when he rented a U-Haul truck and headed down to the warehouse of a tape distributor going out of business to load it up with 650,000 cassette tapes for feeding into Torah Tapes’ ever-voracious tape-reproduction machines.

Many of these millions of tapes — and later, with the advance of technology, CD disks and MP3s — traveled to the furthest reaches of the globe. In the early ’90s, Mayer had been asked to send several thousand tapes for display at a Jewish book fair in Moscow, whose organizers promised they would be promptly returned. When only empty boxes came back, Mayer was upset, assuming that the tapes had been pilfered by the organizers for other uses.

Only many years later did it come to light that the tapes had found their way into the hands of the community of Russian Jewish refuseniks, who were desperate for Torah learning materials. Mayer was ecstatic to learn that these heroic Jews had made good use of his tapes, reproducing them over and over again and distributing them throughout their underground network.

Although Torah Tapes was best known for its ubiquitous tapes on all of Shas, there were many other offerings as well. For a long time, for example, it was the major distributor of Rav Avigdor Miller’s extensive and highly popular library of recorded shiurim. And when Rabbi Eli Teitelbaum started his Dial-a-Daf program, offering a phone line featuring daf yomi and many other shiurim and lectures on a host of topics, a generous loan from an anonymous third party enabled these two great innovators of Torah dissemination to collaborate, with Dial-a-Daf offering telephone access to shiurim and Torah Tapes giving people the opportunity to purchase or borrow tapes of those same offerings.

Initially, Torah Tape patrons would purchase the tapes for a dollar a piece, but later on it moved to a lending-library model, under which borrowers paid a one-dollar-per-tape deposit fee and got 75 cents back for each tape returned. This brought in some income to help defray a portion of the cost, but who footed the lion’s share of the organization’s very significant expenses? One man — Mayer Apfelbaum — absorbed all the costs of employees’ salaries, utilities, tapes, and machinery, and 100–150 UPS packages weekly, investing his own money and never in all the years taking a donation from anyone.

As for supporting his own family, after trying his hand in a few fields like insurance and stocks, Mayer eventually started a cleaning service for yeshivos. He had a crew doing the work and spent a mere handful of hours each week tending to the business, with the balance of his waking hours devoted to Torah Tapes and other chesed endeavors. Every penny for those endeavors came out of his own pocket, from the income of his business and by scrimping on his own living expenses.

“From a financial standpoint,” his son observes, “Torah Tapes was a losing proposition. My father’s thinking was if he were to take the public’s money, it thereby became mammon hekdesh, which must be treated with the utmost discretion. If he would want to purchase a new tape-reproduction machine or computer, he’d have to think, ‘Do I really need this or can I make do with what I have?’ His ehrlichkeit simply wouldn’t allow him to entertain the possibility of mishandling other Jews’ gelt.”

To all appearances, the Torah Tapes headquarters was simply a tape distribution center, humming with nonstop activity. But for seemingly endless hours each day, Mayer was in his office there on the phone, fielding calls from a large circle of people who often kept him on the line interminably, seeking advice, consolation, or simple friendship as only Mayer knew how to provide. For the Jew in prison, the homebound elderly or ill, the divorced or widowed, Mayer was the address. Although people would call ostensibly for tapes, they were also calling to hear a caring voice and a feeling heart, and he in turn had all the time in the world for them.

In Mayer Apfelbaum’s world, everything was a potential springboard for helping others. As his friend Gershon Rothstein describes him, “Mayer helped and helped and helped — with shidduchim and money and advice. He was a person who saw terrible pain and loss all around him and said, ‘I’ve got to do something about that.’ ” He used the job openings at Torah Tapes as yet another opportunity for chesed, often giving positions to people who needed something other than money, like the young fellow living on the margins of the frum community and contemplating leaving it altogether, or the fellow who had fallen on hard times and then into a depression.

He davened at the Mattersdorfer Rav’s Yeshiva Chasan Sofer, which was down the block from his home, but whenever a new shtibel opened in the neighborhood, the first three mispallelim to show up on a Friday night were the Apfelbaums — Mayer and his two boys. They’d continue to attend the fledgling shul regularly during its first few months, until it was on solid footing.

Mayer had someone operating a gemach on his behalf which over many years gave out hundreds of thousands of dollars — only they weren’t actually loans. He told his son, “This gemach has only one side to it,” meaning the lending side, because he knew he’d never get the money back. It was, in reality, just a way to give tzedakah with dignity.

Mendy recalls how it worked: “He’d tell his borrowers, ‘You’ll pay me back, don’t worry. It’s a 25-year loan.’ But it remained a loan forever. To others he’d say, ‘You can pay me a hundred bucks a month.’ But he never cashed those checks. The money just flowed from his account to others. I know, because I managed his account, and he would tell me to whom to give the checks and the cash, and whose loan repayment checks to rip up after they’d bounced.”

For himself, there were few personal needs. The sum total of Mayer’s travels were two trips to Eretz Yisrael and one to Toronto. Yet he was not otherworldly, and understood well what others needed, even if he didn’t. As Mr. Rothstein says, “He was a person who knew very little of himself and knew very, very much of everyone else and pushed everyone around him to go see what they could do for another. And I also saw first-hand how this influenced his children. During Mayer’s final, eight-month-long illness, I visited the house weekly and one of his children was always with him, taking care of him with such gentleness. Two of his grandchildren got married during that period, and each time, one of his children stayed with him and didn’t go to the wedding. I told Mayer many times that I learned kibbud av from his children.”

His experiences during World War II left a deep imprint on his soul, driving him to do ever more and more for others. When one of his children told him about an encounter he’d had with a European Jewish survivor who had questioned where G-d had been during those years, Mayer responded, “The Ribbono shel Olam saved me countless times from certain death and injury. They say, ‘Where was He?’ I say, I know exactly where He was, because I met Him so many times in those years, and I have to spend my life trying to repay a fraction of His kindnesses to me.”

We tend to create mental images of what a tzaddik should look like, although we also know that’s often not how one appears in real life. And for every hidden tzaddik, there might be another one who’s hiding in plain sight. Reflecting on his father’s legacy, his son Mendy says, “The world says my father was a tzaddik, but although we know his incredible accomplishments, the way my siblings and I saw him was simply as an honest-to-goodness ehrliche Jew. Deep-seated yiras Shamayim. Simple emes and yashrus. Someone whose word was good until the end, no matter the cost.”

With characteristic simplicity, Mayer Apfelbaum had expressed two wishes to his children: He wanted no hespeidim at his levayah, just the recitation of some kapitlach Tehillim, and that his matzeivah was to feature nothing but his name and the words “founder of Torah Tapes.” One of his children once called up Rav Shlomo Miller, the eminent Toronto posek and rosh kollel — who, as the son-in-law of Rabbi Moshe Rivlin, is close with the Apfelbaum family — to ask if he had to comply with his father’s request for no eulogies.

Rav Miller said not to worry, because this was Mayer Apfelbaum they were talking about: If that was his wish, his levayah would surely take place on a day when hespeidim were in any event not permitted. And indeed, it did.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 785)

Oops! We could not locate your form.