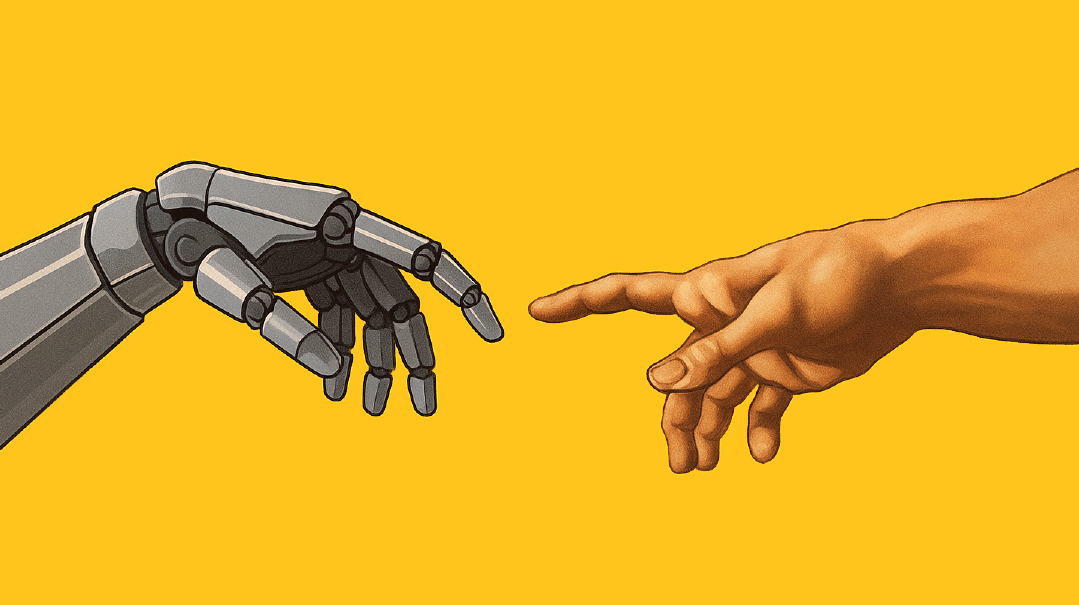

In or Out

In all too many spheres of our existence, COVID has snatched away the possibility of a middle ground

Chances are you know someone who’s attending yeshivah or seminary in Eretz Yisrael this year.

Chances are also good that so many of your own frames of reference for that experience will remain utterly foreign to them. Spur-of-the-moment bus rides to the Kosel, get-togethers with old high school friends over iced coffee and bagels, inspiring Shabbosos spent with special families in Tzfas or Netivot, long conversations at a veteran rebbi or teacher’s dining room table… for most students this year, these chavayot have yet to happen.

In order to open their doors to students from America or Europe, the yeshivos and seminaries had to commit to a long list of COVID regulations. They’ve had to weather an initial quarantine period and a Yom Tov lockdown, in addition to a complete rethinking of the normal programming that makes the experience colorful, varied, and vibrant. How are they coping? Penina Steinbruch’s feature explores their balancing act.

There’s a different, albeit related story, that we didn’t focus on. This is the story of the Israeli yeshivah bochurim and the stark choice they’ve had to make since COVID reshaped their world. If you are a yeshivah bochur learning in an Israeli yeshivah gedolah — the term for a post–high school institution complete with a dorm — there is basically one legal setup for you: the capsule program.

In order to learn in an Israeli yeshivah during COVID, you have to commit to virtually zero exposure to anyone outside of your particular yeshivah during the entire “capsule” period. That means never leaving the yeshivah environs — which are usually limited to a building, not a campus. No walks, no airing out, no quiet time away from the crowds.

There are some boys who thrive under these conditions. The singular focus, the absence of distraction, and the challenge of proving their mettle have elicited their best learning and growth. Others have found the capsules challenging and restrictive. Many yeshivos have done their best to give these boys some flexibility within the guidelines. Even the stricter yeshivos are hosting kumzitz events, or taking the boys on occasional trips to an isolated beach or swimming pool.

Still, despite those occasional perks, the reality remains. If you attend a yeshivah like this, you will never be able to run out and buy a slice of pizza or a falafel fresh from the stand. You will never be able to daven at the local minyan factory. You will miss your friends’ engagements and weddings. You will miss just about every family simchah.

The boys who committed to and continue to stick to these restrictions are surely some of our modern-day heroes. But most people do best with a middle road, and many bochurim realized early on that the capsule program is just too restrictive for them. Where are these bochurim today?

Some are trying to keep up their learning without the physical structure — meeting chavrusas in local shuls, finding unofficial spots in open batei medrash, listening to shiurim on their headphones while trying to stay plugged in to the yeshivah spirit. It’s not a great formula. But these boys are still striving, and you have to admire it.

Then there are the boys who have steadily slipped away from a yeshivah framework and are drifting at the periphery of the community. Might a less severe framework have spelled the critical difference for them? You have to wonder.

There are also the boys who tried to join the capsule program even though it seemed punishingly strict.

I heard the director of a mental health hotline describe a resulting scenario: “I got a call from a rosh yeshivah one day,” he said. “He told me a bochur had joined the capsule, but after a few tense days, he seemed close to the breaking point. ‘I have to get out of here, I have to get out of here, I can’t stay locked in anymore,’ he kept muttering. The rosh yeshivah asked me to come evaluate the bochur — as soon as humanly possible.”

The director asked a professional to come along with him. They met the bochur at the locked yeshivah gate. The professional sounded him out through the bars. The diagnosis was clear; this bochur had to leave before an inevitable breakdown.

“This I can tell you,” the director said in conclusion. “He’ll never be able to go back to that yeshivah. But after that experience, will he be able to go to any yeshivah at all?”

The story haunts me, not just because of the vivid way it paints one boy’s suffering, but also because it encapsulates one of the most terrible effects of this terrible virus: In all too many spheres of our existence, COVID has snatched away the possibility of a middle ground. If you truly care about virus transmission, and you truly care about Torah learning, then your only option seems to be the hermetically sealed yeshivah capsule.

But if you’re a thinking, feeling, emoting human being, something inside you surely recoils at the cost of these stark measures, the absoluteness of the all-or-nothing. We need human contact, we need to be part of a community, we need interaction and shared experience — and we need to be able to take a walk, see the sky and the trees and the birds.

The yeshivah bochurim who made the choice to stay inside so they can learn and keep others safe are our greatest pride. But the price is a steep one: for them, for their friends hanging on by a thread and a phone line, and for the boys who no longer see a place for themselves in the beis medrash.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 842)

Oops! We could not locate your form.