A Man of His Word

“I should not be saying this, Herr Teicher. All the other men signed the document, and you refused to sign. I respect you for that”

Second day of Rosh Hashanah, 1930s.

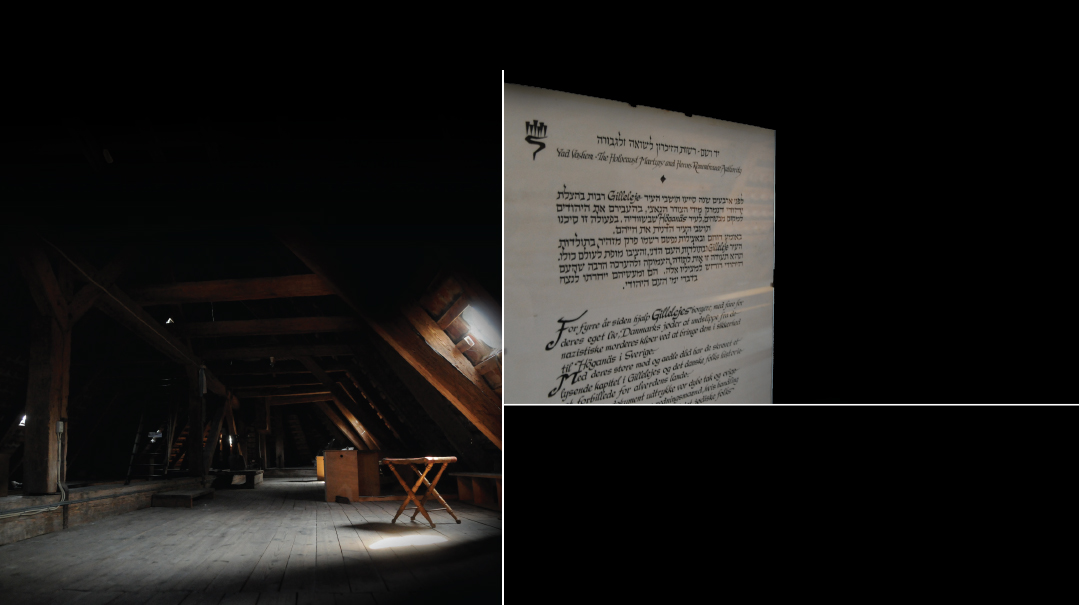

The Chortkover shtibel, Berlin. A band of Nazis had just stormed into the shul and demanded that the men line up to sign a form attesting that they did not own weapons or automobiles. Fearing for their lives, the men queued up and signed.

One man, however, refused to sign.

“Today is a holy day,” Elazar Teicher respectfully informed the Nazi official. “It would be my greatest pleasure to come to the station and sign tonight. But I will not sign today.”

The Nazi responded with a brutal kick. Mr. Teicher fell out of the line, smarting from the blow, yet deeply satisfied that he had avoided chillul Yom Tov.

Later that night, he reported to headquarters to sign the document. Head held high, he presented himself to the same Nazi: “Herr Teicher here to sign the papers.”

The Nazi gaped in astonishment. After deliberating for a moment, he edged closer to Mr. Teicher, and whispered, “I should not be saying this, Herr Teicher. All the other men signed the document, and you refused to sign. I respect you for that.”

Elazar Teicher went through life with this same sense of duty. Once he knew his obligation, he fulfilled it — without hesitation or fanfare. Although during the war he had to bend rules that threatened the very survival of his family, he never lost his sense of responsibility to Hashem or to his fellow Jews.

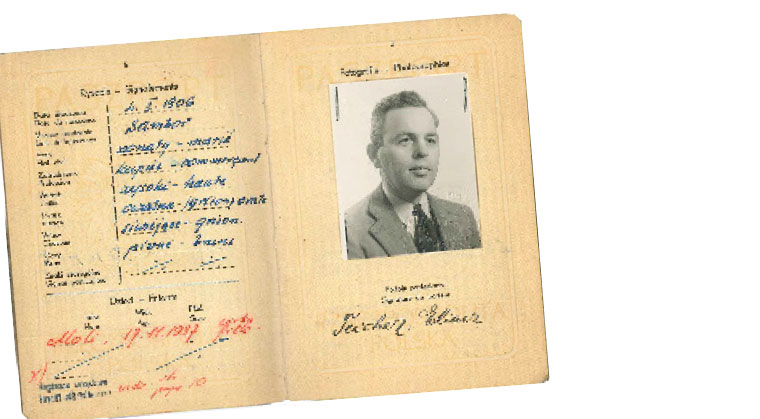

Elazar Teicher was born in Sambor, a city near Lemberg/Lvov, Poland, in 1906. His family moved to Berlin when he was a young child, but he was orphaned of both parents by the time he was 14. This tragedy did not embitter him or dampen his devotion to Yiddishkeit. Refusing to rely on charity while he lived in the Jewish orphanage, Elazar began to work alongside his older brother Tzvi Meier to help support himself and his younger sister Chana. All the while, the young Teicher orphans scrimped from their meager salaries to pay a rebbi to learn with them after work each day. Their dedication helped them resist the rampant assimilation that surrounded them in interwar Berlin. As Elazar’s daughter, Giselle Eisenstein, would later write, “To remain observant in those years was not so simple.” A joke at the time had it that “Berlin is such a frum city that even the shuls are closed on Shabbos.”

Elazar eventually worked his way up to owning his own fur coat factory, along the way acquiring a reputation for integrity that would be his lifelong legacy. “He grew up to be someone who was the most trustworthy person, such an ish emes,” his son-in-law later reminisced.

Mr. Teicher’s high ethical standards translated into high sartorial standards. He was known as a dapper dresser, favoring top hats and light-colored suits. He told his children it was just as important to dress properly as it was to sleep properly.

Elazar’s stylish clothes sometimes created a misperception about his religious outlook. When he visited his wife Ciporah’s hometown of Frysztak, Galicia, the townspeople assumed with his attire he must not be frum. When they watched him daven, however, they realized their mistake. As his son-in-law observed, “Outwardly he looked modern and elegant, but inwardly he was more like a chassid.” Years later in America, he was a sought-after sheliach tzibbur on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

Although during the early years of Nazi rule Elazar still lived with his young family of seven in a fashionable section of Berlin, he was one of the few who foresaw that there was no Jewish future in Germany. But he was not willing to abandon everything and become a refugee dependent upon others for support. So Elazar searched for weeks for someone to buy his factory so he could start over somewhere else.

But there were no takers. Even his longtime foreman sneeringly refused to pay a pfennig for it, boasting he could get it for free if he waited a bit longer. Mr. Teicher, though, could not stomach the thought of that outcome. He considered it a travesty of justice. So he packed up his machinery and had it shipped to Belgium. Not surprisingly, the machinery never reached its destination. But for Mr. Teicher, that didn’t matter so much. A principle had been upheld.

He later made a resolution that had more far-reaching consequences. On one 13th of Kislev in the late 1930s, the chassidim at his shul, Berlin’s Chortkover shtibel, organized a clandestine yahrtzeit seudah for the Chortkover Rebbe — a meeting that was by then strictly prohibited. Elazar, a chassid by birth and aware of the dangers, decided to attend. For the rest of his life, he was grateful for finding that resolve.

In the middle of the seudah, a man ran into shul and banged on the table. “Don’t go home tonight,” he desperately warned, “the Germans are rounding up Jews who are Polish citizens.”

Elazar, who was himself a Polish citizen, hid at the home of Reb Dovid Priever, a naturalized German citizen. Those who stayed home that night — including Elazar’s older brother — were deported, never to be heard from again.

November 9, 1938. Kristallnacht. Elazar Teicher packed his bags and fled with his family from Germany to Belgium. By this point, his concerns about survival outweighed any worries about self-sufficiency. But true to form, he made sure to pay all his taxes before leaving. This surprising act would yield unexpected dividends after the war. Whereas many claimants of reparations could not document their financial losses, Elazar’s proof was stored throughout the war in the most secure of all locations — in the archives of the German government itself.

More travails awaited the Teichers on their flight from Germany. At a border checkpoint inspection, the Nazis took one last opportunity to humiliate escaping Jews. Wielding an outsized pair of scissors, they slashed their way through suitcase after suitcase, reducing the family’s personal effects to shreds. When the border guard reached Elazar’s tefillin bag, the family froze. But Elazar quickly sized up the German and acted boldly.

“Gebetsriemen,” Mr. Teicher stated firmly. “Those are phylacteries. Don’t you dare cut them.”

The Nazi, moved by Elazar’s tone of voice, handed them back and waved the family through.

Elazar maintained his integrity even in the most chaotic circumstances. Fleeing Belgium from the Nazi onslaught in May 1940, the Teichers boarded a train to southern France. The scene was hectic. Passengers threw their luggage out the windows to make room for others, yet the trains still could not hold all the hordes of Frenchmen fleeing the German invasion. Amid this bedlam, though, Elazar spotted an acquaintance who had given him 2,000 Reichsmarks to guard in pre-Kristallnacht Berlin. Now, two years and three countries later, Elazar happily pulled out that exact sum and returned it. (How he was able to keep the money secure during those times remains a mystery.) That money, the man later said, enabled his family to survive the war.

The harrowing nine-day train ride did not, unfortunately, lead the Teichers to safer shores. It deposited them in Vichy France, a collaborationist regime that was ready and willing to hand over its Jews to the Nazis. The family had barely caught their breath before Elazar was arrested by the French police. He was interned in French concentration camps — St. Cyprien and Gurs — while his family remained ignorant of his whereabouts.

But Elazar did not despair; he surveyed his options carefully. In Gurs, he volunteered for the chevra kaddisha, and in exchange, received a coveted privilege: permission to leave the camp and go to town for supplies. Many in his position became black marketeers, buying bread in town and selling it for profit in the camp. But Elazar saw the privilege as an opportunity of a different sort. He would buy as much bread as he could carry on each trip and smuggle it back to the camp, selling it at cost to those less fortunate than himself.

Elazar did not remain at Gurs for long. When he discovered his family was interned in Rivesaltes, he volunteered to join them there. There the family survived on barely 800 calories a day, under treacherous weather conditions. Giselle, Elazar’s oldest daughter, weighed 50 pounds when she left the camp at age 12.

But worse was yet to come. In 1942, the deportations to Auschwitz began. Elazar returned to his family barracks one day, grimly informing Ciporah of an impending transport. She realized immediately that this was not a time for playing by the rules. Thinking quickly, Ciporah hid her husband under a bed and stuffed blankets around him, nearly suffocating him in the process.

Then, a heart-stopping knock. The French police, armed with bayonets, stormed into the apartment in search of Elazar. They combed through the rooms, and then began to scrutinize the suspiciously lumpy bed. Before the eyes of the horrified family, they stuck their bayonets through the mattress numerous times. But miraculously, they did not stab him. According to his grandson, the French gendarmes were not quite as thorough as the Nazis, who probably would have violently upended the entire bed. To the family’s immense relief, the police left after that initial search.

The Teichers realized that escaping the camp was now a top priority. And again, when survival was at stake, Elazar was willing to bend the rules. But it was Ciporah who took the initiative and masterminded their escape. Ciporah noticed that every day, a woman and her daughter climbed into a van, left the camp, and were brought back later that same evening.

“Where do you go every day?” she inquired.

“My husband is in the hospital and he requests that we visit him.”

“And they let you leave every day?” Ciporah asked incredulously.

“Yes, as long as he specifically asks for us, they give us a pass.”

“Well, then,” Ciporah countered, “could you please ask him to request that the Teicher family come visit him?”

The woman did as she was bid and the family, grateful for the ruse, fled to Lyon.

The Teichers barely got to appreciate their newfound freedom before a gentile teacher tipped them off that more roundups were in the offing. Ciporah, desperately searching for a solution, began to notice that people she had seen at the water pump near her apartment every day were slowly disappearing. Curious, she followed a woman one day down a side street, where she spied the woman entering a cellar. Ciporah found a secure lookout and peeked through the small cellar window, realizing as she watched that the woman must be speaking to a smuggling agent. Throwing caution to the wind, Ciporah afterward approached the man herself, got down on her knees, and pleaded with him in broken French to take her family of seven to Switzerland. He agreed — for 1,000 francs a head.

The plan was that a driver would pick them up the next morning from their apartment in Lyon and drive them to a “dark house,” a ramshackle collection point where groups would wait to cross the border. Then, a different smuggler would pick them up from the “dark house” and drive them to the border, where they would be led across the Alps on foot to Switzerland.

An old French Renault pulled up to the Teichers’ apartment the next morning at five. As the family crowded into the car under cover of darkness, they discovered that family friends — the Weingolds — were in even greater peril than they were. The Weingolds were living in a hotel in Lyon by day and sleeping in a park by night to avoid the ever-intensifying police raids. “You’re coming with us,” Elazar decided. The driver did not object. All ten passengers squeezed into the little Renault, children crouched on the floor, adults ducking when they passed other vehicles, until they reached the “dark house” safely.

But there was a glitch. The head smuggler arrived soon after at the “dark house,” and realized immediately that there were too many people and he would not take them all. Ciporah, knowing that her group was responsible for the extra people, hurried upstairs to confer with Elazar. They agreed to offer the smuggler more money. As she crept down the stairs with her new offer, Ciporah heard the smuggler giving orders for the other people to clamber into the waiting van.

She ran back upstairs. “There’s no time for negotiating. We have to leave now.”

It was dark, and she hoped they could sneak into the van without him noticing. He didn’t notice — and by the time he did, they were too far gone to turn back again.

And then came the last stage of escape — trekking through a forested area of the Alps on foot. The guide admonished them not to utter a sound, and to follow him by the light of his cigarette. Elazar carried his youngest daughter, Molly, age four, in a rucksack on his back for the journey. At one point, 12-year-old Giselle’s shoe became stuck in the snow and the group unknowingly went on ahead of her. She couldn’t scream for help — that could give them away — but luckily she was able to link up with a Jewish man and his son and rejoin her parents afterwards. The trek took six hours, and by the time they set foot in Switzerland, Elazar’s white shirt had turned red. His profuse sweating had caused his tie to leach out its color onto the shirt. Apparently, Elazar did not abandon his dapper dress even while on the run from the Nazis. Well-groomed or not, though, they had finally made it to freedom.

Yet being accepted as refugees was not a given. Over nine thousand Jews — including a father and son in line behind the Teichers — were sent back to France at this time. The Teichers are convinced that the Swiss let them remain in the country because they favored families with young children. They had finally reached safe shores — but not complete tranquility. The Swiss did not allow families to stay together. Husbands and wives were housed in refugee camps, and children were dispersed among foster families. Elazar insisted that his children be housed in Orthodox homes, and only four-year-old Molly (this writer’s husband’s grandmother) was allowed to remain with her parents. Elazar took a job in the camp kitchen, enabling him to avoid chillul Shabbos for the duration of the war.

After the war’s end, Elazar looked to America as the best place for raising religious children. He booked tickets through the Jewish Agency — but then found out that their boat was leaving on Shabbos. The Jewish Agency refused to let him board early. He decided, then, that his family was not going.

“Everyone thought he was crazy,” one grandson recounted — those tickets had cost them a fortune.

The local rav even offered to find a heter to allow the family to board on Shabbos.

Elazar replied, “I didn’t ask you a sh’eilah; I don’t need a heter. I was never mechallel Shabbos before and I certainly won’t do so now. It’s not a sakanah.”

Elazar would not go against the rules — the situation was not life-threatening — but that didn’t mean he wouldn’t look for other ways to accomplish his goal. He contacted the shipping company directly and found out that the boat was docking at a different port on a weekday prior to that Shabbos. He packed up the family, rode a train to that port, and boarded early. Elazar was able to keep Shabbos, his integrity, and his tickets.

Elazar’s zeal for mitzvos was as strong in America as it had been in Europe. After docking, he brought his family to Connecticut, to a cousin whose spacious home seemed like paradise to the war-weary family. After unpacking all their belongings, Elazar inquired what time Shacharis was the next morning.

“We’ll be lucky if we have a minyan for Shabbos,” his cousin replied incredulously, as if his greenhorn relative still had much to learn about America.

“Well, then, everyone pack up,” Elazar countered without missing a beat. “We’re going to Manhattan.”

Ironically, Manhattan did not live up to Elazar’s standards either. The Teichers arrived in Manhattan late Thursday night — too late to unpack and also prepare for Shabbos. Upon making inquiries, Elazar learned that “everyone” ate Shabbos meals at a certain restaurant. So he made reservations, and took his family there on Friday night after shul. The Teichers perused their menus, deliberated over all the options, and gave their orders to the waiter. The young man took out a pencil and began to scribble their orders down. Elazar was shocked — and outraged. He gathered his family and strode out of the restaurant. They ate bread and jam that Shabbos.

Elazar displayed the same tenacity for Shabbos when it came to supporting his family in the goldeneh medineh. Despite his excellent work ethic, he was fired on a weekly basis for refusing to come in on Shabbos. Eventually he found a job working for Mr. Solomon Scharf of the Upper West Side as a bookkeeper for his nursing home business, a position Elazar filled conscientiously for the rest of his life.

And Elazar’s personal dealings continued to be marked by his trademark integrity. When Mr. Arnie Klapper, his mechutan’s son, opened an optometry store in Boro Park, Elazar arrived at the shop to be one of the first customers. He picked out a pair of glasses that suited his exacting taste, strode to the front of the store, and pla

ced them on the counter.

“I’ll sell them to you at cost,” Mr. Klapper kindly offered, as he did for all mishpachah.

“I came to you to make my glasses,” Elazar countered, standing perfectly upright, “because I have confidence in you, and not because I want a bargain.”

Elazar Teicher never looked to compromise, he looked to do what was correct — with Hashem and with his fellow man.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 748)

Oops! We could not locate your form.