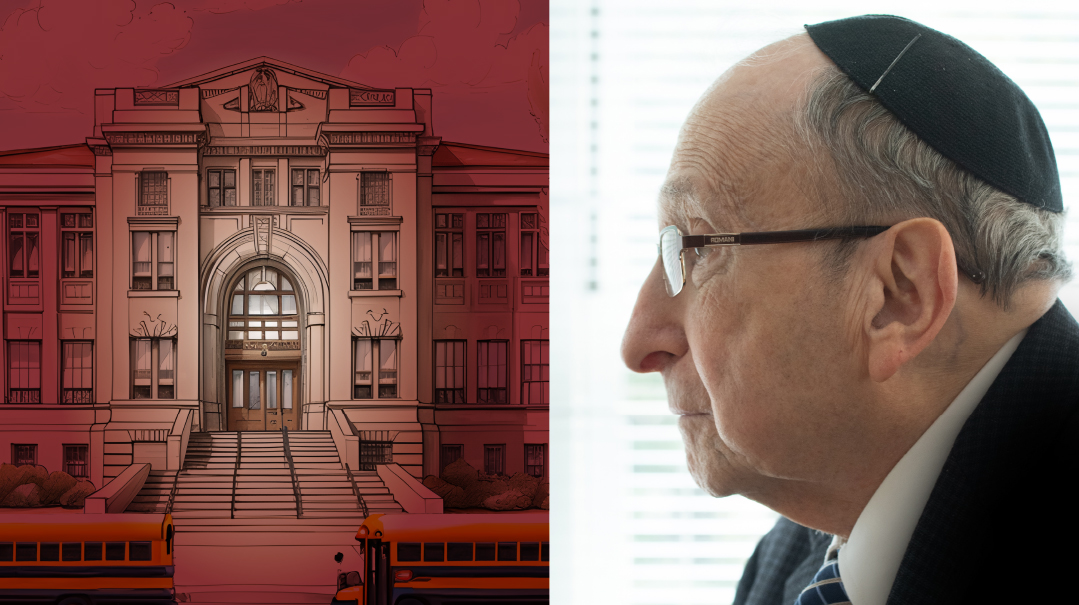

Idealistic Insider

Nine decades in, Seymour Lachman is still the consummate public servant

Photos: Jeff Zorabedian

IT was a lazy spring Saturday in the early 1970s in the mixed Italian/Jewish neighborhood of Bensonhurst, Brooklyn — the kind of afternoon when many of the locals could be found taking in a ball game at the park or polishing their cars.

Not this day, however. Word had leaked that none other than New York City’s Mayor John Lindsay was coming to these parts, bringing the area’s staunchly conservative Italian-American residents out in force in a spontaneous show of displeasure with Lindsay, their liberal Democratic nemesis. Scores of people gathered outside the apartment building on Avenue P which the mayor had come to visit, as shouts of “Down with Lindsay! Down with Lindsay!” reverberated throughout the surrounding streets.

But why in the first place had Lindsay made the trip — police entourage, blaring sirens and all — from Gracie Mansion to Brooklyn, just a few miles from Bensonhurst but worlds away politically? He was there to hold a meeting of the New York City Board of Education at the home of Dr. Seymour Lachman.

The Board — a five-member body charged with setting policy for the city’s sprawling public school system — usually met either at City Hall or at Board of Education headquarters at 110 Livingston Street in Brooklyn. But this time, Mayor Lindsay had convened a Board meeting for a Saturday, and when Lachman learned of it he explained to the mayor that as an Orthodox Jew he would be unable to attend.

“I know about the Sabbath,” the mayor countered. “But I can travel to you, can’t I?” Despite Lachman’s attempt to explain that this, too, was not in keeping with what he called the “spirit of the Sabbath,” the mayor remained unmoved.

That Shabbos afternoon, an official meeting of the Board went forward in the Lachman living room. It was a day to remember for Bensonhurst, but just another day in the colorful life of a consummate public servant, Seymour Lachman.

Over a career spanning decades in academia, politics, and Jewish communal activism, Dr. Lachman has worn many prestigious hats — but always, with a yarmulke proudly perched underneath.

Sitting with Dr. Lachman in the comfortably furnished apartment he shares with his wife, Susan, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, it’s clear that although he’s no longer teaching or politically active, retirement for this nearly 91-year-old isn’t yet on his agenda. Engaged as ever even with a full nine decades behind him, he’s currently hard at work on a soon-to-be-published book — his eighth — this one a memoir of his years as chairman of the Greater New York Conference on Soviet Jewry and his role in advocating for the Jews once trapped behind the Iron Curtain.

Firm as his religious convictions are, however, Dr. Lachman has never been a provocateur looking to flaunt his principles whether others liked them or not. Quite to the contrary, he stresses his belief that it’s both crucial and achievable for disparate segments of society — black and white, Jew and non-Jew, Republican and Democrat — to learn how to get along.

Words into Action

Growing up in 1930s Brooklyn, Seymour was the third boy born to Louis and Sarah Lachman, who had emigrated from Europe between the two World Wars. Against a backdrop of family tragedy — his older brother passed away at age five due to a doctor’s misdiagnosis — Seymour decided early on to devote his life to making a difference in the lives of his people.

“Back in Poland,” he reflects, “my father had been a talmid chacham, someone who spoke six or seven languages. But when he came to America, my earliest memory of him was working for the WPA digging ditches after losing his candy store during the Great Depression. I asked myself, How could this be? This is a great nation, where anyone can do anything. And I told myself I would try do something to benefit not only the Jews of America but all Jews. Although I never explicitly stated it, that was always behind everything I did.”

As a student in Brooklyn College, he became the president of its Hillel chapter and came under the influence of its director, Rabbi Norman Frimer, who later went on to become the international head of the Jewish campus group. “Not only was he my first real mentor in working for the community,” Dr. Lachman observes, “but he also made my life’s most important connection.”

One day Rabbi Frimer’s secretary gave him a slip of paper containing the name and phone number of a Brooklyn College student, Susan Altman, telling him, “You’ve got her name and number. Now you’re on your own.” They’ve now been married for 70 years.

The couple went on to pursue doctoral degrees at New York University, he in history, she in sociology. Seymour worked his way through graduate school, taking a position teaching history in Thomas Jefferson High School, his own alma mater, and then at Lafayette High School.

In Lafayette, he started an extracurricular program called the Amity Club, where kids of different backgrounds could get to know each other and learn to discard biased stereotypes. When he challenged the club’s members to be ambitious and invite one of America’s most famous people to the first Amity event, they invited former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of FDR.

She accepted immediately, but had just one question: “How do I get to Brooklyn? My driver has no idea.” Seymour chuckles at the memory. “Mrs. Roosevelt was known as the First Lady of the World, and indeed had been all over the world but didn’t know how to get to Brooklyn. We once took our kids to the Roosevelt Museum at Hyde Park on Long Island, and lo and behold, in the section about Eleanor Roosevelt, what was on display? A plaque from the Lafayette High School Amity Club! Apparently, it meant enough to her to hold onto it all those years.”

Susan says that this early incident is a window into two important aspects of her husband’s life: “First, he went beyond the role of a teacher. Seymour has had an accomplished life in academics, as a professor and as a dean. But he always translated what he taught into action.

“Second, he always believed that we have to learn to get along. That’s a thread that runs through everything he’s done. We Jews are a people that dwells alone, but that doesn’t mean we don’t need to have understanding and respect for others and do things to foster good relations among all of society’s diverse sectors.”

It was Dr. Lachman’s staunch belief in the importance of societal coexistence, along with his outstanding administrative and interpersonal skills that became among his most important assets once he ascended to a position that was an Orthodox Jewish first: During the 1960s, Lachman served first as chairman of the Kingsborough College history department and then as dean of the college’s mid-Brooklyn campus.

Consensus Builder

In 1969, the state legislature decentralized New York City’s educational system, taking control of the city’s schools away from the mayor. Instead, it created 32 community school boards with oversight over elementary and middle schools and an interim five-member Board of Education to oversee the high schools and make decisions regarding school construction, budgeting and maintenance.

Each of New York’s five borough presidents was entitled to name one member to the Board. At the time, Brooklyn’s borough president was Abe Stark, a secular Jewish clothier famed for his store’s sign at the base of the right-field stands at Ebbet’s Field, the home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, which read “Hit Sign – Win a Suit.” And since Seymour Lachman was an educator long in Brooklyn communal affairs with a reputation as a consensus-builder, Stark gave him the nod as the Board’s Brooklyn representative at the tender age of 35.

Leadership of the Board rotated among its members, and in 1973, Lachman’s turn came to serve as president. It was, and remains, the highest level to which an Orthodox Jew has ever risen with the ranks of New York City government.

Seymour Lachman stresses that although he didn’t wear a yarmulke on the job and many people had no idea about his personal observance, he saw this new high-profile position as a momentous opportunity — and the first thing on his agenda was to pay a visit to one of Orthodox Jewry’s preeminent shtadlanim, Rabbi Moshe Sherer a”h.

“I went to him to ask one question,” Dr. Lachman remembers: “How do you behave in public as an Orthodox Jew? Guide me. I’m young and I need guidance.”

Dr. Lachman regarded Rabbi Sherer as “my rebbi and mentor in how an Orthodox Jew should conduct himself in secular society,” adding that, “I would call him my role model were the standards were not so high.”

Someone Daddy Helped

There were many things about the Agudah leader that deeply impressed Lachman. There was his unwavering commitment to principle even when under intense pressure to conform and compromise, his personal integrity, which to politicians and priests alike meant that Rabbi Sherer’s word could be relied upon, and there was the dignity and grace he projected when interacting with people from all walks of life in society at large.

For his part, Rabbi Sherer not only considered Seymour an ally in the Agudah’s various struggles to protect and advance Orthodox Jewish interests, but also a great asset in repairing the frum community’s image at a time when it was at a particular low point due to certain very public scandals involving Orthodox individuals. In 1975, Rabbi Sherer made a concerted effort, albeit ultimately unsuccessfully, to lobby Governor Carey’s administration to appoint Dr. Lachman to the New York State Board of Regents. The reason, he wrote, was his conviction that “in light of recent blemishes on the public Orthodox Jewish image, it is imperative for us to focus a spotlight on an openly Orthodox Jewish personality in high public office.”

During the prior several years, there had been a strident push among some in the black community for exerting far greater control over inner-city schools, an outgrowth of the emphasis on ethnic identity and differentiation which was a hallmark of the 60s. This in turn led to skyrocketing tensions between blacks and Jews and a prolonged teacher’s strike in the fall of 1968.

But as Lachman later wrote in a book entitled Black White Green Red: The Politics of Education in Ethnic America, his background as an educator in intergroup relations positioned him well to deal with this challenging time in the city’s history. Looking back on his tenure on the Board, he notes such accomplishments as drawing the lines for then-brand-new school districts and creating a structure for the Board to consult with them, as well as codifying for the first time the rights and responsibilities of high school students.

Yet even as he worked for the interests of all New Yorkers, Seymour felt a special responsibility to look out for his own coreligionists. He saw to it, for example, that the city public schools would be closed not just on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur but on all Yamim Tovim.

On one occasion, when a plan was floated to bus white students from Canarsie to attend majority-black schools in East Flatbush, a tug-of-war developed between the rabbanim of the two Brooklyn neighborhoods: The East Flatbush rabbis supported the idea, hoping it would staunch the deterioration of local schools and the surrounding neighborhood, while the others opposed the busing proposal.

Dr. Lachman contacted Rabbi Sherer, concerned that if this rabbinic rift were to go public it would bring dishonor to the Orthodox community. Rabbi Sherer arranged for the two of them to meet with Rav Moshe Feinstein at his Lower East Side home, where the venerable Rosh Yeshivah counseled that the rabbanim on both sides should drop their involvement in the issue.

This was only one of several encounters Dr. Lachman had with Reb Moshe. His son, Rabbi Eliezer Lachman, recalls Rav Moshe Feinstein calling their home one morning to discuss the predicament of a frum teacher in danger of losing his job.

“My father looked into the matter and reported back that the person was actually not competent as a teacher, but my father did commit to trying to find him another position in the school system,” Rabbi Lachman says. “And it wasn’t unusual — on Purim we would sometimes receive a very elaborate mishloach manos, and I would ask my mother who these people were who’d sent them, since I’d never heard of them. And she’d say, ‘That’s someone whom Daddy helped find a job.’ ”

Extra Credit

In 1973, the yearslong effort of Rabbi Moshe Sherer to create an accreditation agency for American post-high school yeshivos came to fruition with the founding of the Association of Advanced Rabbinical and Talmudic Schools (AARTS). Previously, the only way for yeshivah students to qualify for federal funding via student loans was under the so-called “three-letter rule,” meaning that the yeshivah had to show that three accredited schools had granted credits for the yeshivah’s course of study.

Once AARTS came into being, yeshivos could qualify for federal aid without being dependent on receiving credits from secular schools. Its inception also helped to eliminate the then-ongoing scourge of bogus “yeshivos” which had no real students yet claimed to be accredited institutions of higher learning, which had placed a cloud of suspicion over all the yeshivos.

The founding board of AARTS was composed of three leading roshei yeshivah as well as several esteemed Orthodox Jewish academics. It was only natural for Dr. Lachman, who in his position carried responsibility for the nation’s largest school system, to be chosen as one of the latter group.

Upon joining the AARTS board, Dr. Lachman became acquainted with the renowned askan Rabbi Naftoli Neuberger, executive director of Ner Yisroel Rabbinical College, who had been deeply involved in the formation of AARTS from the outset. When it came time for Dr. Lachman to decide where to send his own son Eliezer, then a twelfth-grader in Boro Park’s Yeshiva Toras Emes Kaminetz, he shared his uncertainty with Rabbi Neuberger.

“Send him to me for a year,” Rabbi Neuberger replied. Dr. Lachman did — and that year has yet to end. Rabbi Eliezer Lachman has been in Baltimore ever since, becoming a leading talmid of the great Ner Yisroel rosh yeshivah Rav Yaakov Weinberg, who was also on the AARTS board. To date, Reb Eliezer has published two well-received seforim containing his rebbi’s shiurim on Rambam, and is now is a rosh kollel and a recognized figure on Baltimore’s Torah scene.

Not long after Dr. Lachman decided to send his son to Ner Yisroel, he received a phone call from a professor who wanted to share his worries about his own son. The young man, a student at the University of Pennsylvania, was in the process of becoming a baal teshuvah and had been sending his non-frum father newspaper clippings describing Seymour Lachman’s career highlights in an effort to demonstrate that one can be religiously observant and still achieve success in the world at large.

“I have an only son,” the father began, “to whom I’ve tried to give every advantage for success in life. I sent him to an Ivy League school, where he’s been doing very well, but recently something has come over him. He’s been exploring religious Judaism and now he wants to drop it all and enroll in a religious seminary.”

Dr. Lachman inquired as to which yeshivah his son was considering. “It’s a school in Baltimore,” the professor said. “Oh, Ner Yisroel — that’s the one my son will be attending next year!” Dr. Lachman told him. “Maybe your son and my son can study together….” Indeed, the next year, that young man and Eliezer Lachman became chavrusas. Today he’s a marbitz Torah of note in Eretz Yisrael, and during his time in the Ner Yisroel kollel, his father actually moved to Baltimore to be close to his son.

Speaking with Seymour and Susan Lachman, one can’t miss their very palpable nachas in their son’s accomplishments in Torah. As Agudath Israel’s current executive vice president Rabbi Chaim Dovid Zwiebel recalls, “Throughout all the years I’ve known him, Dr. Lachman spoke about his children often and you could see his tremendous pride in the fact that they are bnei Torah.”

The Lachmans are no strangers to longtime Torah learning: Susan’s brother, Rav Yitzchok Yosef Altman, has been learning full-time for decades in Bnei Brak’s renowned Kollel Chazon Ish, and Seymour’s uncle Yitzchok, his father’s only sibling to survive the war, spent his entire life learning after arriving in Eretz Yisrael.

Dr. Lachman has his own significant connections to the yeshivah world. During his many years living in Bensonhurst, he maintained an ongoing kesher with Yeshiva Beis HaTalmud. In addition to attending Rav Bromberg’s Leil Shabbos shiur, he learned with Reb Moshe Swerdloff, a Beis HaTalmud stalwart who would go collecting for the yeshivah with Rav Leib Malin and whose children are prominent talmidei chachamim.

Reb Eliezer recalls that at the kiddush tendered in honor of his sister Sharon’s marriage to Aaron Chesir, Rav Binyomin Zeilberger, one of the roshei yeshivah of Beis HaTalmud, rose to speak. “You think,” he said, motioning to the father of the kallah, “that Dr. Lachman is a professor? He’s a Yid who, if he drops a spoon on the floor and a gadol b’Torah sitting next to him tells him it’s a fork, he’ll say it’s a fork.”

The Rosh Yeshivah had zeroed in on a singular hallmark of Seymour Lachman’s career in public service: The willingness to submit to the counsel of Torah leaders. When Rabbi Moshe Sherer learned that the top leadership post had become open at the Board of Jewish Education, an umbrella group for both Orthodox and non-Orthodox schools, he approached Dr. Lachman about putting his name in the running. Dr. Lachman was concerned, however, that it would mean bearing responsibility for channeling money to Reform and Conservative schools. And indeed, when Rabbi Sherer posed the question to the members of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah, the response was that they could not permit a frum Jew to take the position.

Back from Oblivion

After stepping down from the Board in 1974, Dr. Lachman returned to the academy, serving over the next four decades in a series of roles at numerous New York-area universities: professor of educational administration at Baruch College; distinguished professor in government at Adelphi; special deputy to the president of Brooklyn College; university dean for community development at CUNY.

Yet even after returning to the private sector, Dr. Lachman’s passion for bringing potential antagonists together to help them find commonalities of interest continued. Many of his successes, he says, “came from doing things behind the scenes, without my name being made public.”

He founded and chaired, for example, the National Collaborative of Public and non-Public Schools. By creating a space for dialogue, he hoped to reduce the chasm separating two educational communities at sharp odds with each other (although both professed to place children’s interests first).

Rabbi Chaim Dovid Zwiebel recalls when he began working for the Agudah in 1984 and had his first exposure to Seymour Lachman. “He worked in a very tangible way on bringing the public and nonpublic schools together, bringing together all the various players. Dr. Lachman’s vision was that educational resources need not be a zero-sum game, where if one community gets funding, it means less for another community. These conferences continued throughout the 1980s into the 1990s, and they were very valuable for me as a way of making new contacts and creating relationships with people in the public school bureaucracy and teachers unions. I know Rabbi Sherer also considered them very important.”

One initiative in which Dr. Lachman played an indispensable, albeit little-known role, and which had a transformative impact on New York’s frum community, was the founding of the Agudath Israel neighborhood preservation organization known as the Southern Brooklyn Community Organization (SBCO). By the mid-1970s, it increasingly seemed that Boro Park, the city’s largest frum neighborhood, might go the way of other once solidly Jewish areas which had declined and emptied of their long-time residents. Pockets of blight on Boro Park’s outskirts in the form of abandoned buildings and gang activity threatened to trigger the kind of mass Jewish flight which places like East Flatbush and Crown Heights had experienced not so long before.

At the time, the concept of neighborhood preservation was very much in vogue across the country, and the Ford Foundation took a particular interest in the cause of preserving ethnic neighborhoods. As it happens, one of the hats Seymour Lachman wore in the mid-70s was that of a consultant to the Ford Foundation, and he approached its vice president, Mitchell Sviridoff, about starting a similar effort in Boro Park. He highly recommended Agudath Israel as the ideal Jewish group to spearhead the project, and spoke of the sterling reputation of its head, Rabbi Sherer, for integrity and competence.

His pitch worked, and the foundation indeed contributed most of the start-up money needed to open an office and hire staff. Rabbi Shmuel Lefkowitz was hired to head the fledgling organization at a glatt-kosher luncheon at the foundation’s offices. After rehabilitating the 15th Avenue section of Boro Park by replacing blighted buildings with new multifamily housing, SBCO moved on to do the same in other parts of the neighborhood and expanded to nearby Kensington, too.

Behind the Scenes

Dr. Lachman had been involved in the Brooklyn political scene for many years, but in 1996 he took things to a new level. He accepted the Democratic Party nomination for the New York State Senate seat in Brooklyn’s 22nd legislative district that became vacant when the incumbent, Martin Solomon, gave the seat up to become a judge.

Seymour won the seat in a special midterm election, and was then reelected four times to full two-year terms. Although his district encompassed some of Brooklyn’s frum strongholds, his constituency was always predominantly non-Jewish.

“I was probably the most conservative Democrat in the Senate,” he reflects. “I was fearful of the extremes in both parties. Politically, my fellow legislators never really knew what to expect from me — I was a total enigma to them. On a personal level, they couldn’t understand my religiosity, and they couldn’t understand why in public I would never eat and drink with them. But I stood my ground on ethical and moral matters, and if they were going to a place where they knew I couldn’t go, they would tell me beforehand.”

Agudah’s Rabbi Zwiebel has fond recollections of Seymour Lachman’s eight-year tenure in Albany. “His strength was in bringing people together, and he was well-respected and a good schmoozer. In the Senate, he was a helpful behind-the-scenes player, and we found that he was most effective playing defense. As a Democrat in a Republican-controlled Senate, he wasn’t really able to sponsor legislation on issues important to us, but when bills were introduced in the legislature that could have negatively affected our community, he would get in touch to discuss them with us and was very receptive to our input. He was well enough respected by his Senate colleagues that he was typically able to modify these bills to mitigate their negative impact and to make sure we were equitably included in certain programs.

“People sometimes say it’s a wasted vote to put a member of the minority party into office,” Rabbi Zwiebel continues, “but Dr. Lachman proved that’s not necessarily the case. There are times when a legislator’s good standing with his colleagues and his people skills can enable him to get harmful legislation dropped or modified. When he left the Senate, we missed him.”

No Love Lost

For his part, however, Dr. Lachman didn’t miss Albany at all. By the time he left in 2004, giving up a safe seat to which he was sure to be reelected, he had become deeply disillusioned with the systemic cronyism and corruption he discovered in the state capital.

One of the lessons he says he learned from his time on the Board of Education is that, “the voices of the public must be listened to,” and at the beginning, he naively believed that’s how things worked in Albany, too.

But then he discovered that virtually all decisions were made exclusively by the proverbial “three men in a room” — the Governor, the Senate Majority Leader and the Speaker of the Assembly. Members of the Senate and Assembly were essentially powerless, voting to rubber-stamp bills they hadn’t read, during legislative sessions they hadn’t attended.

Two years after stepping down, Dr. Lachman detailed this sordid reality in his book Three Men in a Room: The Inside Story of Power and Betrayal in an American Statehouse, a stinging insider’s exposé of the deep dysfunction plaguing one of America’s largest governments. As he writes, “So much about Albany breeds cynicism, so much of it stinks — the closed-door meetings, lobbyists insisting on quid pro quo, and vast amounts of questionable spending obscured by secrecy and sleight-of-hand.”

Although the book puts forth various ideas for reforming New York’s state government, in the 17 years since its publication, virtually nothing has changed in New York’s sick political culture. Indeed, in 2017 Dr. Lachman wrote a sequel entitled Failed State, in which he demonstrates that it’s still crooked business-as-usual in Albany.

In one passage in the 2006 book, he describes being summoned toward the end of his third term to meet with the Senate Majority Leader, Republican senator Joe Bruno. The Republicans were in the process of redrawing the boundaries of several New York City districts to increase their Senate majority, and after some initial pleasantries, Bruno showed Dr. Lachman a Brooklyn redistricting map.

On it, Lachman’s current district had disappeared entirely, having been divided up among four other districts. It was a not-very-subtle message that his seat was going to be gerrymandered out of existence unless he agreed to cooperate. Bruno got right to the point: “Seymour, you’re a reputable guy. We’ll give you the safest Democratic seat in Brooklyn.” He went on to promise Dr. Lachman two to three million dollars to spend in his district as he saw fit: All he had to do in return was either switch parties or remain a Democrat but vote with the Republicans.

Then Governor George Pataki called in and Bruno put him on the speakerphone. “ ‘We’d love to have you in the Republican Party,’ the governor told me,” Dr. Lachman says. “Bruno chatted with him some more and when he hung up, at first I was feeling disconcerted, but I recovered soon enough.

“ ‘I have always been a Democrat and will remain a Democrat,’ I said. And I walked out.”

Retribution came swiftly, with Bruno making good on his threat, chopping up Lachman’s district into four. And as a result, one of the largest Jewish communities in the country became part of four districts instead of one — a dilution that was a blow to its political clout.

Lachman decided to run anyway in one of those districts, and won once again. He was well-liked by his constituents and likely could have gone on being reelected over and over again, but after two more years, he’d finally had enough of Albany’s self-dealing. He retired from the political arena with his head held high for not having gone along just to get along.

The back cover of Three Men in a Room features a quote from Edmund J. McMahon Jr., the director of the Empire Center for New York State Policy, calling the book an “invaluable dissection of Albany’s dysfunction from the perspective of an idealistic insider who emerged from the experience with his principles and credibility intact.”

And that’s all you need to know about Seymour Lachman.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 987)

Oops! We could not locate your form.